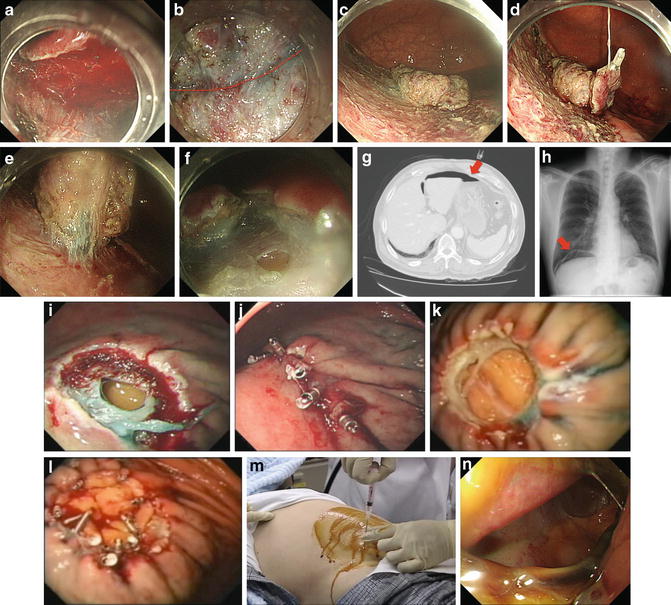

Fig. 17.1

(a) Before changing position. (b) After changing position. (c) Clipwith-line attached on the underside of the specimen. (d) After “Clip-with-line method”. (e) Perforation occurrence during esophageal ESD. (f) CT showed mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema. (g) “Target sign” of the resected specimen of esophageal EMR. (h) Perforation closed successfully using endoclips (same case as Fig. 17.1e)

Closure of the entire mucosal defect is not usually necessary, as delayed perforation is extremely rare. Additionally, prophylactic coagulation of visible vessels in the resection area after esophageal ESD is not usually necessary. Delayed bleeding is relatively rare in the esophagus and excess coagulation may instead cause undue delayed perforation.

Identification

During or after ER, the muscularis propria layer can be recognized as fibers that run transversely underneath the submucosal layer. This is likely because the esophagus does not have a serosa. Therefore, when a defect of such fibers is seen, a perforation must have occurred (Fig. 17.1e). Subsequently, subcutaneous emphysema can be recognized as “snow-ball crepitation” on the neck and/or chest if a substantial amount of air has escaped. Chest computed tomography (CT) or radiograph may show mediastinal or subcutaneous emphysema, with CT having a higher sensitivity of detection (Fig. 17.1f) [16, 18]. Even if the muscularis propria is not exposed, mediastinal emphysema can occur more than 50 % of the time due to air insufflation [18]. In EMR cases, a “target sign” on the resected specimens, indicating resection of the muscularis propria, may suggest a perforation (Fig. 17.1g) [19]. Though delayed perforation is rare, it can be a life-threatening event. Therefore, it is essential to appropriately suspect, identify and treat as soon as possible. Generally, patients are kept fasting for a few days after ESD. During this period, delayed perforation should be suspected if fever or chest pain occurs.

Treatment

Shimizu et al. reported 3 cases of successful closure of esophageal perforations after EMR with endoclips [5]. Perforations during esophageal ESD have also been managed by closure with endoscopic clips and conservative medical treatment [7]. However, this clipping method itself can injure the muscle and actually make the perforation larger. In such cases, the entire mucosal defect should be closed. Esophageal perforation may lead to life-threatening conditions such as severe mediastinal emphysema or mediastinitis.

When perforation does occur, the defect should be closed with endoclips (Fig. 17.1h). However, if the application of clips hinders the continuation of ER, such as would be the case in ESD, the resection should be continued. Once sufficient space has been created around the perforation, the clip(s) can be applied to the defect and submucosal dissection can then be continued. In some cases, ESD can be converted to EMR in order to complete the procedure. After the procedure, the patient should be kept fasting with antibiotics administered intravenously for several days.

In cases of delayed perforation, mediastinal emphysema and mediastinitis can occur. It is still a controversial issue that surgical interventions are needed immediately. If conservative treatments are not effective, surgical interventions should be considered.

Stomach

Incidence

The rates of perforation during gastric EMR and ESD have been reported as 0.5–5.3 and 1.2–9.6 %, respectively [20–32]. The risk factors for perforation during gastric ESD are the following: lesions in the upper third of the stomach, larger lesions, and lesions with ulceration [25, 31, 32]. Delayed perforation after gastric ESD has been reported to occur in approximately 0.5 % [33].

Prevention

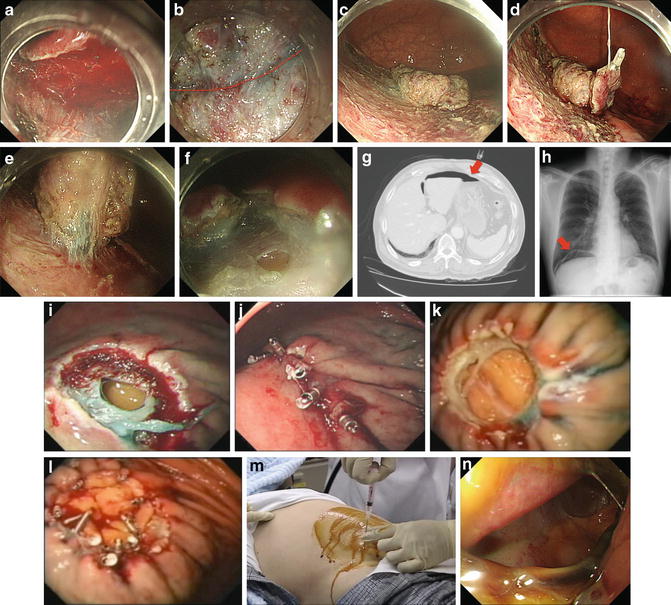

Preventions of perforation in gastric ESD are similar to the previously mentioned methods for esophageal ESD. If the lesion is located on the greater curvature of the gastric body, identification of the muscularis propria may be difficult due to frequent bleeding (Fig. 17.2a); thus, adequate hemostasis is essential in order to avoid perforation. If there is severe fibrosis beneath the lesion, dissection of submucosal fibers can be difficult, and occasionally, injury of the muscularis propria can occur. In the setting of severe fibrosis, the endoscopist should imagine the curve of the proper muscle layer and dissect little-by-little, using the knife in a very careful manner (Fig. 17.2b). The “clip-with-line” countertraction method is also useful in assisting dissection in these cases (Fig. 17.2c–e). However, one should dissect carefully, because the curve of the muscle layer may change due to excess tension on the clip.

Fig. 17.2

(a) Blood made confirmation of the submucosal layer difficult. (b) The imaginary curve of the proper muscle layer with severe fibrosis (red dotted line). (c) Before “Clip-with-line method”. (d) Clip-with-line attached on the underside of the specimen. (e) After “Clip-with-line method”. (f) Perforation occurrence during gastric ESD. (g) CT shows “free air” in abdominal cavity (arrow). (h) Abdominal radiography shows “free air” under diaphragm (arrow). (i) Perforation occurrence after gastric EMR. (j) Perforation closed successfully with “single-closure method”. (k) Perforation occurrence after gastric EMR. (l) Perforation closed successfully with “omental-patch method”. (m) Paracentesis for aspiration of intraabdominal air. (n) A large delayed perforation (defect of the entire resected area)

Closure of the entire mucosal defect is not always necessary, as delayed perforation is a rare event.

Identification

During or after ER, the muscularis propria can be recognized as fibers that run transversely or longitudinally underneath the submucosal layer. The stomach has a thicker muscularis propria, especially in the antrum. The stomach also has serosa; therefore, even if the muscularis propria is injured, perforation does not always occur (Fig. 17.2f). However, if both the muscularis propria and the serosa are injured, this likely leads to pan-peritonitis. Abdominal CT and abdominal/chest radiography may reveal “free air,” confirming leakage of air into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 17.2g, h).

Though delayed perforation is relatively rare, it may require surgical intervention. Therefore, it should be recognized as soon as possible. Generally, patients are kept fasting for a few days after ESD. During this period, delayed perforation should be suspected if the patient is suffering from fever or abdominal pain. Abdominal CT and abdominal/chest radiography are also useful in confirming perforation by free air and/or contrast leak.

Treatment

Closure of perforation using endoscopic clips after snare excision of a gastric leiomyoma was first reported by Binmoeller et al. in 1993 [34]. In 2006, closure with endoscopic clips for EMR/ESD-related gastric perforation was reported to be effective in a large series of consecutive cases [22]. Two methods of endoscopic closure using endoclips have been reported, including the “single-closure method” and the “omental-patch method” [22]. The single-closure method is performed to treat small defects and starts from the edge of the perforation rather than the center (Fig. 17.2i, j). The omental-patch method is performed on relatively larger defects by suctioning either the greater omentum or the lesser omentum into the stomach lumen and then clipping the omentum as a patch to the edges of the perforation (Fig. 17.2k, l). However, if the clips make the continuation of ER difficult (such as in ESD), and the patient’s condition is stable, the procedure should be continued before clips are applied. The clips can then be placed once sufficient dissection has been performed. In some cases, ESD should be converted to EMR in order to complete the procedure. If there is leakage of a large amount of air, the increase in intraabdominal pressure can result in potentially fatal hypotension—so called “abdominal compartment syndrome or tension pneumoperitoneum.” In such cases, the pressure of the intraabdominal cavity must be reduced immediately. This can be achieved by performing paracentesis to aspirate intraabdominal air. After testing for pneumoperitoneum with a 23-G needle attached to a syringe filled with water, decompression of the pneumoperitoneum must be performed with a 14- or 16-G puncture needle with side slits (Fig. 17.2m). Then, the patient is kept fasting and an antibiotic is administered intravenously for a few days. If the patient suffers from fever over 38 °C or chest pain, an endoscopic examination with CO2 insufflation should be performed to evaluate that the defect still is closed or reopened.

When delayed perforation is diagnosed, pan-peritonitis must have occurred due to leakage of gastric acid, bile and pancreatic juices; therefore, surgical intervention may be necessary even if endoscopic closure has been performed successfully. In some cases, large delayed perforations occur, which may encompass the entire resected area (Fig. 17.2n). In such cases, surgical treatment is most definitely necessary.

Duodenum (Non-ampullary)

Incidence

There are few reports of ER in the duodenum. In these limited reports, the rates of perforation during EMR and ESD have been reported as 0–3.8 and 0–21.4 %, respectively [35–47]. The corresponding rates of delayed perforation have been reported as 0–3.8 and 0–20 %, respectively. Compared with the stomach and the esophagus, the incidences of immediate and delayed perforation seem to be relatively higher in the duodenum, particularly in ESD cases. The reasons may be that the duodenal wall is the thinnest among these three organs. Additionally, it is especially difficult to manipulate and stabilize the endoscope in the duodenum. Inoue et al. proposed that extensive piecemeal EMR for large lesions and the high concentration of digestive enzymes in the duodenal lumen are also reasons for the high incidence of delayed perforation [44]. In this study, all cases of delayed perforation were associated with lesions located distal to the major ampulla. The authors concluded that lesions treated with piecemeal EMR or ESD and located distal to the major ampulla are especially prone to delayed perforation.

Prevention

Though the methods of preventing perforation are the same in duodenal as in esophageal and gastric cases, as previously described, it is especially difficult to operate and stabilize the scope in the duodenum. Therefore, duodenal ESD should be performed with great care, and it may be necessary to terminate the procedure if significant difficulty is encountered.

Inoue et al. reported two cases of delayed perforation after prophylactic clipping [44]; therefore, there is no evidence that clipping decreases the incidence of delayed perforation. However, in our opinion, in order to prevent delayed perforation, closure of the mucosal defect by prophylactic clipping should always be performed if possible. Recently, Mori et al. reported two cases of complete closure of post-ESD duodenal ulcer using an over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) [48]. This technique may be effective for prevention of delayed perforation.

Identification

The very thin muscularis propria in the duodenum can be recognized as fibers that run transversely underneath the submucosal layer. If a defect of these layers is noticed, perforation must be considered. Because the duodenum is a retroperitoneal organ, a delayed perforation located on the posterior wall will not present with pneumoperitoneum. Patients may present with fever, but, unlike gastric perforation, symptoms of retroperitoneal perforation are generally mild [44]. Therefore, delayed perforation should be suspected and abdominal CT performed for confirmation even if patients’ symptoms are mild.

Treatment

If duodenal perforation occurs, endoscopic closure should be performed, similar to cases of esophageal and gastric perforation, if the patient’s condition is stable. Kaneko et al. reported two cases of successful closure of duodenal perforations after EMR for duodenal carcinoid tumors with endoclips [49]. However, endoscopic clipping of duodenal perforation is difficult because the lumen is narrow and tortuous [47]. Failure to close the perforation endoscopically may lead to severe complications due to leakage of bile and pancreatic juice. In such cases, surgical treatment would likely be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree