Chapter 29 Hysterosalpingography

INTRODUCTION

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a radiographic procedure used to image the uterine cavity and demonstrate tubal patency by injecting radiographic contrast media through the cervix (Fig. 29-1). Along with documentation of ovulation and semen analysis, HSG is one of the fundamental infertility tests. The technique is easy to learn and perform, is relatively low-cost, and has an acceptable radiation exposure and few complications. More than 200,000 HSG procedures are performed annually in the United States.1

HISTORY

HSG was first performed in 1910 when Rindfleisch injected a bismuth solution transcervically followed by an abdominal X-ray. HSG has been the standard initial test for assessing the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes since Heuser used Lipiodol in 1925.2 Fluoroscopic control replaced static films in 1947.3 The procedure has remained essentially unchanged since then.

ACCURACY

HSG should be considered a screening test; as such, it should have a high sensitivity so as not to miss the opportunity to treat an abnormality but with a low false-positive rate to prevent unnecessary additional testing and treatments. The accuracy of an HSG is highly dependent on technique and interpretation. The technical quality of the HSG is important to limit misinterpretations (i.e., eliminating air bubbles that may be confused with a polyp or myoma or using inadequate contrast volume or injection pressure to demonstrate tubal patency). In one study 50 HSG films were reviewed by five reproductive endocrinologists. There was considerable variability in the interpretation as well as the recommended clinical management.4 In another study, three reproductive endocrinologists and three radiologists reviewed 50 HSGs on two occasions. The intrareader and inter-reader reliability was high for the detection of normal uterus and tubes, as well as tubal obstruction, but low for the detection of hydrosalpinges, uterine adhesions, pelvic adhesions, and salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Clinicians more reliably diagnosed hydrosalpinges and tubal obstruction; radiologists more reliably detected salpingitis isthmica nodosa and uterine adhesions.5

Diagnosing Uterine Cavity Abnormalities

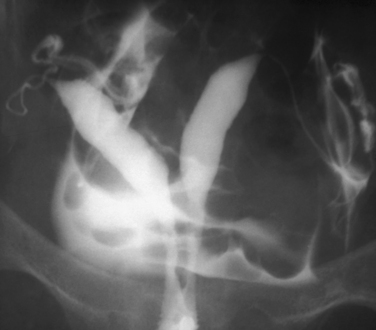

HSG has a high sensitivity but a low specificity for the diagnosis of uterine cavity abnormalities.6 HSG and diagnostic hysteroscopy performed on 336 infertile women showed that HSG had a sensitivity of 98% but a specificity of only 35% due to difficulties distinguishing between polyps and myomas. False-negative results were mild intrauterine adhesions of doubtful clinical significance.7 Thus, HSG fulfills the requirements as a good first-line screening test for revealing abnormalities of the uterine cavity, although any abnormalities found will likely need further evaluation to make a definitive diagnosis. Sonohysterography or diagnostic hysteroscopy can distinguish between polyps and submucous myomas, which appear similar on HSG (Fig. 29-2). A uterine septum and a bicornuate uterus cannot be differentiated on an HSG (Fig. 29-3). Evaluation of the external fundal contour by laparoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or three-dimensional ultrasonography is required to make a definitive diagnosis. The arcuate uterus has a mild convex fundal margin and is a normal variant. Extrinsic compression from an intramural fundal myoma may give a similar appearance and is easily recognized on routine transvaginal ultrasonography.

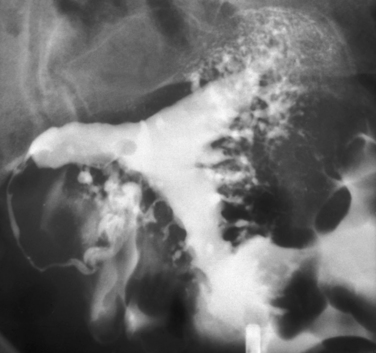

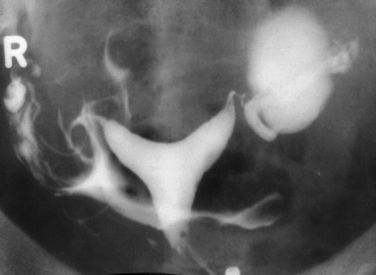

Other conditions visualized on HSG are adhesions, changes caused by diethylstilbestrol (DES), and adenomyosis. Adhesions appear as irregular filling defects and may be very mild or completely obliterate the cavity (Fig. 29-4). DES was used from the 1940s up to 1971 as prophylaxis for spontaneous abortions. The classic appearance associated with in utero DES exposure is a hypoplastic T-shaped cavity. (Fig. 29-5). Adenomyosis can occasionally be diagnosed by HSG as a cavity with shaggy borders (Fig. 29-6). The sensitivity for detecting this condition is unknown because it is uncommon in younger women and is definitely diagnosed histologically after hysterectomy.

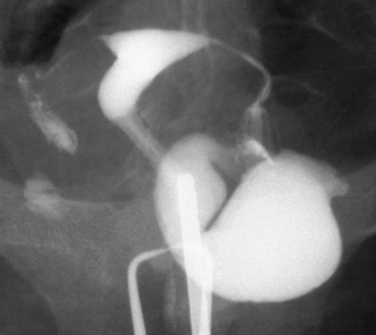

Figure 29-5 Hypoplastic and T-shaped uterine cavity associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol.

Diagnosing Tubal Abnormalities

An evidence-based study found HSG to be “a valid and accurate diagnostic test to be applied in a general population of subfertile couples to assess tubal patency but an unreliable test for diagnosing tubal occlusion.” Tubal blockage on HSG is not confirmed by laparoscopy in up to 62% of patients, but if HSG suggests patent tubes, tubal blockage is highly unlikely. Laparoscopy is needed to confirm or exclude tubal occlusion on HSG.8 It should be noted that laparoscopy is not the perfect gold standard; 2% of patients with bilateral tubal occlusion subsequently conceived spontaneously.9 One study noted that 60% of patients with proximal tubal occlusion on HSG were patent on repeat HSG 1 month later.10

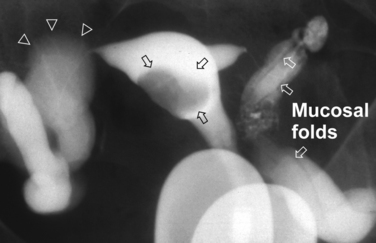

Surprisingly, hydrosalpinges may be both overdiagnosed and underdiagnosed by HSG. They may be only mildly dilated with preservation of mucosal folds or massively dilated with complete loss of the normal intratubal architecture (Fig. 29-7). HSG can also diagnose salpingitis isthmica nodosa. This condition, which predisposes to tubal occlusion and ectopic pregnancy, is similar to adenomyosis of the uterus in that there are diverticuli from the mucosa into the muscularis (Fig. 29-8). HSG is also not an ideal test for diagnosing pelvic adhesions because it detects them in only half of the cases in which they are present.2 Adhesions are usually diagnosed on HSG by the presence of loculated spill of contrast medium (Fig. 29-9).

INDICATIONS

HSG is part of the basic infertility workup and is normally required in every patient.11 It is still the first-line technique for excluding anatomic defects in the uterine cavity and documenting tubal patency in infertility patients. A 1994 survey of board-certified reproductive endocrinologists in the United States reported that 96% obtained an HSG as part of the basic infertility workup.12 In addition to its role in assessing the uterus and tubes, HSG may have a therapeutic effect.

Hysterosalpingography has also been the mainstay for diagnosing uterine cavity abnormalities in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Such abnormalities have been reported in 15% to 27% of these patients. The most common anomaly is the septate uterus; surgical correction improves the live birth rate from 3% to 20% to 70% to 90%.13 Because tubal status is not an issue with these patients, HSG may be replaced with sonohysterography.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Active Pelvic Infection

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an uncommon but potentially serious complication of HSG. Active cervicitis, endometritis, or salpingitis are absolute contraindications to performing an HSG. Cervical cultures for gonorrhea and chlamydia, a white blood cell count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate should be obtained to rule out an active infection in patients with adnexal tenderness. They may also be considered in patients with a history of prior PID.

Severe Iodine Allergy

Patients with a history of severe iodine allergy may elect to forgo HSG in favor of diagnostic laparoscopy and hysteroscopy or sonohysterosalpingography. However, the risk of a severe reaction with HSG is small because the volume of contrast (most of which escapes vaginally) is small and it is not injected intravascularly. If a decision is made to proceed with HSG in patients with known iodine allergy, a nonionic water-soluble media such as Hexabrix (ioxaglate), Isovue 370 (iopamidol), or Omnipaque (iohexol) should be used because the incidence of iodine allergy is lower with them.2 Patients with severe iodine allergy should be premedicated with prednisone 50mg administered 13 hours before HSG and diphenhydramine 50mg 1 hour before. In a study in 563 patients with a history of anaphylactic reactions to iodine contrast treated with this protocol, there were fewer than 10 reactions, none life threatening.14

Endometrial Carcinoma

It is felt to be prudent to avoid performing HSG in known or suspected cases of endometrial carcinoma for fear of disseminating tumor cells and worsening the prognosis for survival. Studies on using HSG for the diagnosis and follow-up of endometrial carcinoma noted that injecting contrast media under low pressure is unlikely to disseminate tumor cells and that it is doubtful that shed cells have the potential for independent metastasis.15 The 5-year survival in endometrial carcinoma patients evaluated with HSG was not significantly different in those who had positive washings after the procedure versus those who did not. Venous or lymphatic extravasation also failed to influence survival rates.16

Pregnancy

HSG is scheduled immediately after menses to prevent performing the procedure in the presence of an unrecognized pregnancy due to the concerns of disrupting the pregnancy as well as radiation exposure. Before the advent of pregnancy testing and ultrasonography, HSG was performed specifically to diagnose pregnancy, with no untoward effects.2 HSG during inadvertent pregnancy is uncommonly reported. In a recent case report the calculated dose to the embryo was 3.7 mGy. The authors state that the teratogenic risk with less than 20 mGy during the first trimester does not justify pregnancy termination.17 The possibility of spontaneous abortion should be discussed with the patient.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Analgesia

Unfortunately, most patients experience uterine cramping during the HSG, but the entire procedure usually only lasts about 3 minutes and the discomfort resolves rapidly at the end of the procedure. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing 1 g of acetominophen to placebo taken 30 minutes before HSG found no significant difference in mean pain scores during or 24 hours after the procedure.18 Several studies noted that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did provide significant analgesia for HSG.19–21

Two randomized, placebo-controlled studies found no difference with intrauterine anesthetics delivered before the HSG. Patients in both studies also received an NSAID, which may have decreased pain enough to mask any beneficial effect of the anesthetic.22,23 There are no references on the use of paracervical blockade for HSG.

Oil-soluble versus Water-soluble Contrast Media

The water-soluble media and oil-soluble media camps have been arguing the relative merits of their favored contrast for decades; as yet there is no clear winner. Water-soluble media offers better image quality because the higher density oil-soluble media tends to obscure fine details in the uterus and tubal mucosal folds. Also, because water-soluble media dissipates quickly, there is no need for delayed films, whereas 1- to 24-hour delayed films are necessary with oil-soluble media. Oil-soluble media also carries increased risks for oil embolism and granuloma formation. Proponents of oil-soluble media counter that water-soluble media causes increased pain on peritoneal spill, although it is mild and very transient. Water-soluble media with lower osmolality may cause less irritation and discomfort.2 The procedure should be performed with the smallest volume of contrast possible to provide the needed information. The biggest argument in favor of oil-soluble media is that it has higher postprocedure pregnancy rates. Most still advocate water-soluble media because it provides better uterine and ampullary mucosal detail and has no serious secondary effects.3,6

Types of Cannulas

Rigid metal cannulas have been the standard device for performing HSG because they are inexpensive, reusable, and readily available. A balloon catheter can be employed in rare cases when cervical stenosis or an inadequate cervical seal prevent completion of the study with the rigid cannula. In addition to the cost of the disposable balloon catheter, it is more difficult to manipulate the uterus compared to a rigid cannula with a tenaculum. Also, the balloon obscures the lower uterine segment. One study reported that the balloon catheter caused significantly greater pain after the procedure.24 However, a randomized study found that HSG performed with a balloon catheter required less contrast and fluoroscopy time, produced less patient discomfort, and was easier for senior residents to perform. It has the additional advantage of allowing the clinician to perform immediate selective salpingography and transcervical tubal catheterization for proximal tubal occlusion without the need to replace the cannula or reschedule the patient.25 A randomized study comparing the rigid cannula to a cervical vacuum cup cannula reported that HSG performed with the disposable vacuum device was quicker to perform, required less contrast and fluoroscopy time, caused less patient discomfort, and was easier for senior residents to perform.26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree