Chapter 26 Hormonal Contraception

INTRODUCTION

Despite the continued development of effective contraceptive methods and increased educational efforts, unintended pregnancies continue to be a major problem in the United States. According to the National Survey of Family Growth, half of a total of 6.3 million pregnancies in the United States in 1994 were unintended, and 1 million of these pregnancies occurred while using oral contraceptives.1,2 Clearly, the need remains for development of improved contraceptive methods.

HISTORY

The history of the development of “the pill” is fascinating. At the turn of the 20th century, an Austrian professor of physiology, Ludwig Haberlandt, demonstrated that pregnancy could be prevented in mice by giving them oral extracts from mice ovaries.3 In the 1940s, Dr. Carl Djerassi, working for the pharmaceutical company Syntex, discovered that the removal of the 19 carbon from yam-derived progesterone increased its progestational activity. This discovery led to the synthesis of norethindrone, an orally active progestin, in 1951.3,4

Modern Hormonal Contraceptives

A broad range of contraceptive hormones and delivery systems are presently available in the United States today (Table 26-1). Several of the newer hormonal delivery systems are parenteral, and some of the preparations no longer need to be taken daily. The most frequently used and best studied are the combination oral contraceptives that contain a synthetic estrogen and one of several progestins. Three progestin-only oral contraceptives are currently available. In addition, a vaginal patch, a vaginal ring, a single rod implant, and an injectable medroxyprogesterone are commercially available.

Table 26-1 Formulations of Some Modern Hormonal Contraceptives

| Delivery System | Estrogens | Progestins* |

|---|---|---|

| Oral contraceptives | Ethinyl estradiol (dose: 20–50 μg) | Estranes: |

| Combination (constant dose) | Mestranol (dose: 50 μg) | |

| Combination (sequential*) | Ethinyl estradiol (20–40 μg) | |

| Progestin only | ||

| Transdermal patch | Ethinyl estradiol | Norelgestromin |

| Vaginal ring | Ethinyl estradiol | Etonogestrel |

| Injectable | Medroxyprogesterone acetate (depot form) | |

| Subdermal implant† | Etonorgestrel |

* Sequential oral contraceptives have changing doses of estrogens, progestins, or both throughout the cycle.

ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Patient Selection

Oral contraceptives are an excellent contraceptive choice for many patients who are willing and able to consistently take a daily pill. In some cases, oral contraceptives may be recommended to patients because of their noncontraceptive benefits, such as treatment of dysmenorrhea or acne. The vast majority of healthy women can take oral contraceptives with an extremely low risk of serious side effects or risks. However, there are several standard contraindications to use of hormonal contraceptive methods that contain estrogen (Table 26-2). Many of these women are good candidates for progestin-only contraceptives. The remainder should be counseled to use an alternative nonhormonal method.

Table 26-2 Contraindications to Use of Combination Oral Contraceptives

| Contraindication (current or past history) | Combination (estrogen-containing) | Progestin-only |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Contraindications | ||

| Suspected pregnancy | X | X |

| Undiagnosed uterine bleeding | X | X |

| Liver disease | X | X |

| Symptomatic gall bladder disease | X | X |

| Breast cancer | X | X |

| Estrogen-induced liver tumor | X | |

| Thromboembolism | X | |

| Cerebral vascular disease | X | |

| Coronary heart disease | X | |

| Estrogen-dependent tumors | X | |

| Seriously impaired liver function | X | |

| Relative Contraindications | ||

| Age > 35 years with any cardiovascular risk factors: | X | |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Hypertension | ||

| Abnormal lipid profile | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Known cardiovascular disease | X | |

| Severe headaches: vascular or migraine | X | |

| Hypertension | X | |

| Diabetes | X | |

| Gallstones | X | X |

| Within 3 weeks of childbirth | X | |

| Breastfeeding (especially first 6 weeks) | X | |

| History of cholestasis of pregnancy | X | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | X | |

| Abdominal or lower extremity surgery contemplated within 4–6 weeks | X | |

| Lower leg cast | X | |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | X | |

| Use of drugs that interact with oral contraceptives (e.g., rifampin) | X | |

Estrogens and Progestins

Estrogens

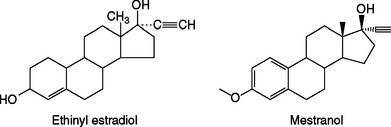

Combination oral contraceptive pills contain one of two synthetic estrogens: ethinyl estradiol or, less commonly, mestranol. Both of these steroids are created by adding a 17-α ethinyl group to estradiol to increase potency and enhance oral activity by impeding hepatic degradation (Fig. 26-1). Natural estrogens are relatively weak when given by mouth due to their rapid clearance from blood by the liver (i.e., the first-pass effect). As a result of decreased degradation, both of these synthetic estrogens are 10 to 20 times more active than estradiol when given orally, but have similar potency when given intravenously.

The original formulation for oral contraceptive pills contained as much as 150 μg of synthetic estrogen each. When studies found an association between the estrogen content of early oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism, researchers found that the estrogen component could be significantly reduced with no loss of contraceptive efficacy. As a result, most modern oral contraceptive pills now contain between 25 and 35 μg of ethinyl estradiol, and a few contain as little as 20 μg.5 Although reducing the daily estrogen dose to either 30 or 35 μg has been shown to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, no study has shown that further decreasing the estrogen dose reduces the risk further.

Progestins

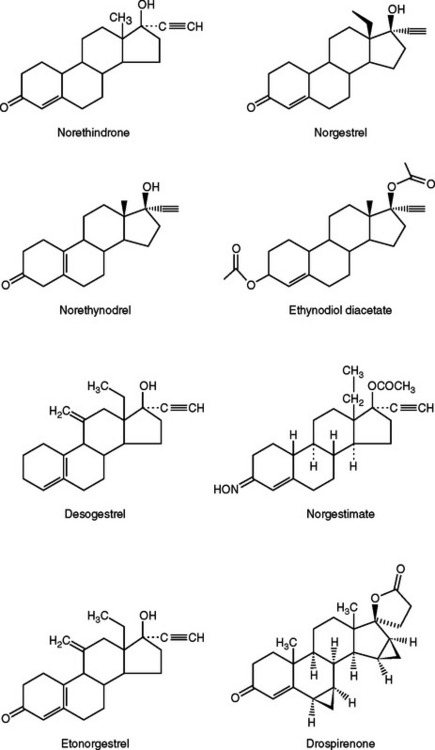

The prototype progestin used in modern oral contraceptive pills is norethindrone (an estrane), which is created from progesterone by adding both a 19-carbon methyl group and a 17-α ethinyl group similar to ethinyl estradiol (Fig. 26-2). Norgestrel (a gonane) is the 18-carbon-ethyl derivative of norethindrone and is a racemic mixture of dextronorgestrel and levonorgestrel. Levonorgestrel is the biologically active component of norgestrel.

Recently, drospirenone, a somewhat unique progestin, has been introduced in the United States.6 This anti-androgenic analogue of spironolactone has a high binding affinity for progesterone and mineralocorticoid receptors, but a low binding affinity for the androgen receptors. Oral contraceptives containing this progestin are associated with less fluid retention but have a slight theoretical risk of hyperkalemia.7 Women with renal insufficiency, hepatic dysfunction, or adrenal insufficiency should not use oral contraceptives containing drospirenone.

COMBINATION ORAL CONTRACEPTIVE PILLS

The majority of oral contraceptive pills on the market today contain both an estrogen and progestin in tablets that are taken daily for 21 days out of each 28-day cycle (see Table 26-1). During the remaining 7 days, women are instructed to take either inert pills (to assist the patient in maintaining the daily habit of taking a contraceptive pill) or no pills at all. At least one modern contraceptive pill gives women a lower dose of estrogen alone during 5 of these remaining 7 days. Extended-use oral contraceptives refers to an approach where active combination oral contraceptive pills are taken daily for 84 days followed by a 7-day hormone-free period.

Efficacy

Approximately 7% of women using combination oral contraceptives will have an unintended pregnancy during the first 12 months of use.8 Rates reported in different clinical trials can be highly variable because of factors, including methodology, demographics, various types of bias, and methods of calculating rates.9–12 Two of the most common methods are the Pearl index and life table analysis.

Life table analysis is more effective for comparing failure rates than the Pearl index because a separate failure rate is determined for each month of use.12 Life table analysis also allows separate evaluation of both method and user failure rates. Method failure rates refer to pregnancy rates that occur when the method has been used correctly, in a consistent manner, and according to the instructions in the package insert. User failure rates (i.e., typical failure rates) refer to pregnancies that occur when the method is not used correctly. The reported method failure rates for oral contraceptive pills are between 1% and 3% and user failure rates are approximately 7%.11 Both method and user failure rates are similar for women over age 30 who are in higher socioeconomic groups. In contrast, the user failure rate is much higher for teenagers and unmarried women, sometimes surpassing 30%.

NONCONTRACEPTIVE BENEFITS OF COMBINATION ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Decreased Risk of Ectopic Pregnancies

Combination oral contraceptives reduce the risk of ectopic pregnancy by 90%.13 The likely mechanism is through suppression of ovulation, an effect that obviously prevents all types of pregnancy. In contrast, some studies have indicated that women using progestin-only oral contraceptives are at higher risk for an ectopic pregnancy than the general population.

Decreased Risk of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Several studies have shown that oral contraceptive use reduces the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) by 50% to 80% compared to women who use no method or a barrier method for contraception.13–15 However, one recent multi-center study failed to show a protective effect of oral contraceptives.16

Decreased Risk of Malignancies

Endometrial Cancer

Multiple case-control and cohort studies have shown that oral contraceptives protect against endometrial cancer.17–19 The overall reduction in risk is up to 50% and begins 1 year after initiation of use. This protection increases with the duration of use and persists for up to 20 years after oral contraceptives are discontinued. The strength of the protective effect varies according to the existence of other risk factors, such as obesity and nulliparity. The purported protective mechanism of action is a reduction in the mitotic activity of endometrial cells by the action of the progestin component of oral contraceptives.

Ovarian Cancer

Multiple case-control and cohort studies have shown that the use of oral contraceptives protects against the development of ovarian cancer.20–22 The overall risk is decreased by 40% to 80%. The effect begins about 1 year after initiating use and decreases by 10% to 12% for each year of use. Protection persists for 15 to 20 years after discontinuation of the oral contraceptives.

Several mechanisms have been proposed by which oral contraceptives might reduce ovarian cancer risk. Suppression of ovulation has been hypothesized to reduce the frequency of “injury” to the ovarian capsule that occurs during ovulation. Suppression of gonadotropins by hormonal contraceptives might also play a role. Finally, data from a primate model suggests that hormonal contraceptives can induce ovarian apoptosis, which in turn eliminates surface epithelium inclusion cysts, thus reducing ovarian cancer risk.23

Colorectal Cancer

Multiple studies have demonstrated up to a 40% reduction in colon and rectal cancer among women who have used oral contraceptives.24–26 However, one study did not find a protective effect of oral contraceptives.27 Theoretical protective mechanisms include a reduction in bile acid production and concentration, and effects on colonic mucosa or flora.28

Decreased Menstrual Flow and Dysmenorrhea

Up to 75% of young women will experience some degree of dysmenorrhea, and 15% to 20% will have severe pain.29,30 Multiple studies have shown that combination oral contraceptives reduce both menstrual flow and dysmenorrhea.29–34

Two possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain how oral contraceptives reduce dysmenorrhea. Women taking oral contraceptives have been shown to have reduced prostaglandins in the menstrual fluid. It is hypothesized that by decreasing prostaglandin production by the uterus, oral contraceptives decrease dysmenorrhea by decreasing either endometrial vasoconstriction and ischemia or uterine contractile activity.35,36

Decreased Benign Breast Disease

Several studies have shown a 30% to 50% decrease in the incidence of benign fibrocystic breast changes in women using oral contraceptives.37,38 One of the clearest effects is a decrease in the occurrence of fibroadenomas among current and recent long-term users of oral contraceptives under age 45. The most likely mechanism is through suppression of ovulation and therefore inhibition of the breast cell proliferation that normally occurs in the first half of an ovulatory menstrual cycle.

Ovarian Cysts

Cyst Formation

It has been commonly accepted that moderate- and high-estrogen oral contraceptives (≥50 μg ethinyl estradiol) protect against cyst formation, although the data supporting this are somewhat inconsistent. Unfortunately, current low-estrogen (≤35 μg) formulations appear to have no effect on ovarian cyst formation.39–41 However, these studies examined cysts found on ultrasound rather than symptomatic cysts. It remains to be seen whether low-estrogen (≤35 μg) oral contraceptives decrease the risk of symptomatic ovarian cysts. Interestingly, progestin-only oral contraception may actually increase the frequency of functional ovarian cysts, according to one small study.42

Cyst Resolution

Many clinicians prescribe combination oral contraceptives to women found to have an ovarian cyst in an effort to accelerate its spontaneous resolution, presumably by decreasing gonadotropin secretion centrally. However, there are no data to support the use of oral contraceptives to expedite the resolution of existing functional ovarian cysts. One cross-sectional study found that ovarian cysts resolved independently of treatment with oral contraceptives.43

Improved Acne

Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that some combination oral contraceptives will reduce acne lesions by as much as 50%.44 Several combination oral contraceptives containing new-generation progestins (e.g., norgestimate, desogestrel) or progestational anti-androgens (e.g., drospirenone in the United States, cyproterone acetate overseas) have been shown to be able to effectively reduce acne. Although it is likely that many other pill formulations will reduce acne, most formulations have not been studied for this outcome.

Increased Bone Density

The majority of studies indicate that oral contraceptives have a positive effect on bone mineral density, and no studies have demonstrated a negative effect.45 Oral contraceptives appear to delay or prevent the decline in bone mass that begins between ages 30 and 40. Women who use oral contraceptives for 5 to 10 years or longer are afforded the greatest protection. A population-based, case-control study revealed a 25% reduction in hip fracture risk in these women.46

Improvement in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Oral contraceptives appear to diminish both the severity and symptomatology of rheumatoid arthritis but do not prevent this disease. A large meta-analysis of nine hospital and population-based studies suggested that oral contraceptives prevent the progression of rheumatoid arthritis to more severe varieties.47 However, the protective effect was noted in the hospital- based studies only, suggesting the possibility of some unexplained bias.

METABOLIC CHANGES RELATED TO COMBINATION ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Insulin Resistance

The effect of combination oral contraceptives on carbohydrate metabolism has been studied for several decades. It is now recognized that both estrogens and progestins affect glucose metabolism by increasing peripheral resistance to insulin. However, studies of women on current low-estrogen (≤35 μg) formulations have shown minimal changes in glucose and insulin levels that are of no clinical significance.48 Further, there is no evidence that combination preparations increase the risk of subsequently developing diabetes in women at risk, such as those with prior gestational diabetes.49

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome who usually demonstrate some degree of insulin resistance benefit from oral contraceptives. Although oral contraceptives may slightly increase their insulin resistance, they also reduce associated symptoms such as acne and hirsutism, regulate menses, and protect the endometrium against development of endometrial malignancy.50

Insulin-dependent diabetic women can use oral contraceptives with little fear of affecting fasting plasma glucose, insulin requirements, or glycosylated hemoglobin levels.51 However, one should avoid oral contraceptives in diabetics with evidence of vascular disease because of their increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Changes in Lipids

The estrogen component of combination oral contraceptives causes elevations in serum triglycerides but has a favorable change on the other two major lipids by elevating high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) while lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels.52 Contraceptive formulations containing progestins with low or no androgenicity (e.g,. desogestrel, drospirenone, or norgestimate) lower LDL-C and elevate HDL-C and triglycerides. In contrast, contraceptive formulations containing more androgenic progestins may change lipids in an unfavorable direction by lowering HDL-C levels and elevating LDL-C levels.6,52–54 It is important to be aware of these differences when prescribing oral contraceptives to women with risk factors for cardiovascular disease or to those who have strong family histories of ischemic heart disease or substantial lipid abnormalities.

Coagulation Changes

Low-estrogen (≤35 μg) oral contraception formulations are associated with clinically insignificant changes in both procoagulant and anticoagulant factors.55,56 However, women with risk factors for venous thromboembolism, such as factor V Leiden mutations, should avoid combination oral contraceptives.

MAJOR RISKS OF COMBINATION ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Cardiovascular Risk

Venous Thromboembolism

Multiple studies have established that women taking combination oral contraceptives containing 50 to 100 μg of ethinyl estradiol are at a small but increased risk of venous thromboembolism.57,58 It soon became clear that the risk correlates with the estrogen dose. When compared to women taking low-estrogen (≤35 μg) pills with an age-adjusted relative risk of venous thromboembolism of 1, women taking intermediate-estrogen (50 μg) pills are found to have a relative risk of 1.5, and women taking high-estrogen (>50 μg) pills have a risk of 1.7.59 However, even in the highest risk group, the absolute risk of venous thromboembolism was extremely low, at only 10 events per 10,000 women-years of use.

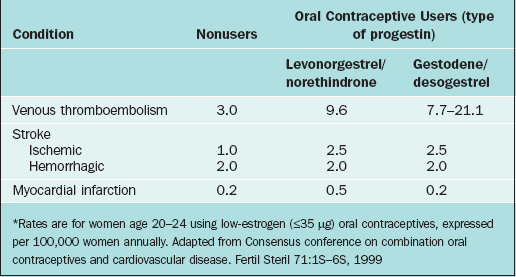

There is some evidence that two of the newer generation progestins might also increase the risk of venous thromboembolism. Two studies published a decade ago suggested gestodene and desogestrel had a greater risk for venous thromboembolism than previously used progestins, such as levonorgestrel.60–63 Subsequent analyses and reviews have failed to reach consensus about whether these finding are real or somehow spurious.64–71

The relative incidence of venous thromboembolism in young women taking low-estrogen (≤35μg) pills with different progestins is given in Table 26-3. At worst, the attributable risk of using oral contraceptives containing gestodene or desogestrel is only about 18 additional cases annually per 100,000 users compared to nonusers. Other risk factors for venous thromboembolism include age, obesity, pregnancy, trauma, smoking, immobilization, recent surgery, medical conditions such as cancer or collagen vascular disorders, and inherited coagulation disorders. Surprisingly, there is no evidence that cigarette smoking or varicose veins appreciably increases oral contraceptive users’ relative risk of venous thromboembolism.72

The mortality due to venous thromboembolism is low in reproductive-age women using oral contraceptives. Age significantly increases this risk of mortality, such that women age 44 have twice the mortality as women age 35.

Factor V Leiden Mutation

The most common genetic cause of primary and recurrent venous thromboembolism in women is factor V Leiden mutation. The identification of the factor V Leiden mutation in 1993 has led to new insights into the relationship between oral contraceptive use and venous thromboembolism.73 White women have approximately 5% prevalence of a homozygous mutation; African-American and Asian women have a much lower prevalence. Women with this mutation not using oral contraceptives have a risk of venous thromboembolism of approximately 5.7 events per 10,000 women-years. In contrast, women with this mutation using oral contraceptives have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism of 28.5 events per 10,000 women-years.

Screening women who desire oral contraceptives for factor Leiden V mutation would not be a cost-effective strategy in light of the low absolute risk of venous thromboembolism in women with this mutation. It has been calculated that screening 1 million potential oral contraceptive users for all known coagulation factor deficiencies or mutations would identify approximately 50 women at risk but also would result in approximately 62,000 false-positive results.69 However, screening women with a strong family history of thromboembolic events for factor V Leiden mutation remains appropriate. Certainly, a known homozygous or heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation is a relative contraindication to estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives, although the absolute risk of thromboembolism in these patients is still relatively low.

Stroke

Ischemic Stroke

Low-estrogen (≤35 μg) oral contraceptives do not increase the risk of ischemic stroke in women with no additional risk factors (i.e., nonsmoking women younger than age 35 without hypertension).74 However, women with risk factors do have a somewhat increased risk. Mortality from oral contraceptive-related strokes is less than 2 per 100,000 cases.

The risk of ischemic stroke in oral contraceptive users is directly proportional to estrogen dose, in a manner analogous to the risk of venous thromboembolism.72,74–77 The risk of ischemic stroke is increased fivefold in women using higher estrogen (≥50μg) compared to low-estrogen (≤35μg) oral contraceptives.78 This risk is not influenced by progestin type or duration of pill use.72,74

Age is the most important independent risk factor for stroke. The relative risk of ischemic stroke doubles as women reach age 40 to 44.74 Stroke mortality also increases by about sixfold once women reach age 35 to 44.72

Other important risk factors include hypertension, cigarette smoking, and migraine headaches. These risk factors appear to interact with oral contraceptive use to substantially increase the risk of ischemic stroke.78–81

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree