Fig. 1.1

Howard Kelly and his cystoscopic-guided ureteral catheterization using freshly waxed tips. Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

In this historical sojourn, the development of light-guided devices will follow a theme. First, the development of direct and indirect light-guides which forms the basis of all types of endoscopes in medicine, from laparoscopy to colonoscopy and ureteroscopy, will be presented. Second, the methods for delivering better illumination will be pursued. This is closely related to the development of image improvement through rod-lens systems, to the modern utilization of fiber optics. Finally, camera systems allow the urologist to multitask which is so fundamental to modern or historically more accurate, current ureteroscopy [7].

Brief Historical Overview

A quick overview here in the introduction is followed by a more detailed historical development. The word endoscopy is derived from Greek meaning “to examine within.” The first lighted examinations were external openings to the gastroenteral tract and the female introitus. Early Roman specula have been unearthed that record the foundations of primitive endoscopy (Fig. 1.2). Early practitioners of medicine realized that viewing a viscus from the inside should provide valuable information in the management of illnesses [8]. Bozzini in 1806 recognized the need to build a direct light to facilitate the examination or the operation of visceral structures [9]. Waxed candles and mirrors provided the illumination for the first endoscope (Fig. 1.3). Daniel Colladon demonstrated light guiding at the University of Geneva in 1841 (Fig. 1.4) [10]. Total internal reflection of light made for a spectacular demonstration and this mechanism was quickly artificially simulated by fellow physicist, Auguste de la Rive, using an electric arc light [3]. Jacques Babinet also took the method to use bent glass rods to examine difficult regions of the oral cavity in 1840 [3]. The Paris Opera began to use the same methods for spectacular stage effects in 1849 “Elias et Mysis” and again in 1853 for Gounod’s Faust [3].

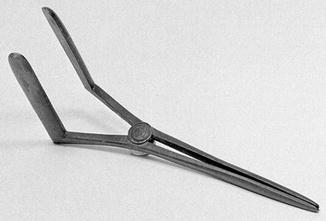

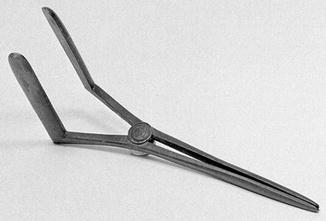

Fig. 1.2

An ancient Roman speculum unearthed at Pompeii. Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

Fig. 1.3

Philip Bozzini’s Lichtleiter. Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

Fig. 1.4

Daniel Colladon’s illustration from his “light guide.” Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

Desormeaux in 1867 developed “open tube” endoscopy for examination of the genitourinary tract and was the first to identify that lenses serve to condense the light source beam to a narrower brighter region that allows for more intricate observations [11]. Bevan in 1868 utilized such a device to remove foreign bodies in the esophagus using a ¾ inch diameter, 4 in. length tube with a reflecting mirror [12]. Waldenburg in 1870 lengthened these instruments and referred to them as “telescopes.” In 1881, American entrepreneur William Wheeler developed a “light pipe” which he hoped to deliver light to every household, but the incandescent bulb would become his chief rival (Fig. 1.5) [3]. The International Health Exhibition held in South Kensington of 1884 displayed a giant “illuminated fountain” created by Sir Francis Bolton [3]. Stoerk in 1887 designed a right-angled endoscope to allow greater manipulation away from the ocular [12]. In that same year, Charles Vernon Boys developed a method of creating small stretched almost pure silica fibers that could transmit light [13]. Rosenheim in 1895 employed a flexible rubber obturator for safer introduction and easier handling of endoscopes [14]. Kelling in 1897 designed a true flexible scope with small interdigitating metal rings covered by rubber on the outside [15].

Fig. 1.5

Wheeler’s light tubes for bringing lighting into American homes just prior to Edison’s incandescent lamp. Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

Killian in 1898 first used cocaine anesthesia during bronchoscopy [16]. Nitze in 1879 pioneered the first modern endoscope for cystoscopy (Fig. 1.6) [17]. He worked with an optician (Beneche), an instrument maker (Leiter), and a dentist (Lesky) to create a 7 mm. deviating prismed endoscope with a liquid cooled glowing wire of platinum [18]. He followed this later with a separate light source, a miniature electric globe (Mignon Lampchen, Fig. 1.7) [19]. In the United States, Otis designed a new cystoscope with telescopic lenses and a distal electric globe. The instrument maker for this scope was Reinhold Wappler (1900) and clearly became the premier optical system of that time. In 1936 Schindler worked with Wolf (an optical physicist) to design the first working flexible endoscope with steel spiral construction and 48 lenses [18]. As early as 1893, Albert Musehold described an apparatus to photograph the endoscopic appearance of the pharynx [20]. Nitze published the first photographic atlas of the pathology of the urinary bladder in 1893 [21]. On December 30, 1926, Clarence Weston Hansell, an RCA engineer, wanted to view images from a distance using fiber-optic bundles [22]. Henning and Keihack published the first color photographic pictures of the stomach in 1938 [23] (Rudolf Schindler developed a rigid, then a semirigid gastroscope and Heinrich Lamm tried to reproduce Hansell’s findings with fiber optics as a third-year medical student using commercially available optical fiber) [3]. Lejeune produced the first motion pictures of the larynx in 1936.

Fig. 1.6

Maximilian Nitze’s cystoscope and images from his 1894 book. Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

Fig. 1.7

Mignon bulbs utilized in early cystoscopes. These were direct current or battery-driven electrically illuminated endoscopes. Courtesy of the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History

Abraham Cornelius Sebastian van Heel noted that cladding improved the light transfer and image quality of fiber optics and speculated that it could be used for cystoscopy in a letter he published in Nature [24]. Harold Horace Hopkins also published in the same volume of Nature with a young graduate student named Narinder S. Kapany, but their fibers were unclad [25]. Basil Hirschowitz (a physician) and Lawrence E. Curtiss (a physics student, later transferred to the American Cystoscope Makers, Inc.) working at the University of Michigan produced a fiber-optic gastroscope which was first tried on Hirschowitz and then presented at the annual meeting of the Optical Society of America in October 1956 in Lake Placid (site of the first digital televised sporting event using fiber optics) [26]. Numerous modern advances have contributed to our modern arsenal of endoscopic equipment (fiber-optic bundles, superheated halide element light sources, electronic charged-coupled devices, CCD, and others) [27, 28]. The need to be able to visualize and eventually operate with tiny endoscopic manipulators is increasingly apparent. This represents the foundations upon which this discussion is based. Advanced ureteropyeloscopic surgery is based entirely upon those pioneer efforts from long ago that strived to better visualize the vital structures of patients suffering with assundried maladies without opening them [29, 30]. The ureters were always present and simply awaited pioneer endoscopists to explore the limits of technology.

Early Endoscopic Development

Most likely, the first instrument described for peering into the recesses of the human body was a rectal speculum. Hippocrates’ treatise on fistulas clearly mentions this technique and later, Galen’s Levicom refers to the catopter which is an anal speculum. Phillip Bozzini (Germany) in 1805 constructed an instrument called “lichtleiter” for the viewing of the openings in the human body [31]. Bozzini’s insight into the potential for direct visualization of the body is as amazing as the harsh criticism of his peers regarding his endoscopic adventures utilizing his device. Bozzini’s light guide consisted of a housing in which a candle was placed. Open tubes of various sizes and configurations could be placed on one side [9]. He then devised a reflecting mirror between the visual tract and the candle light so that the light would be reflected only toward the targeted organ and not backward into the examiner’s eye. The opposite side of the system was the eyepiece. He had published his results in 1806 and began to lecture in 1807 and even tried to have prospective studies of the instrument performed in military hospitals of the time [31]. This development was remarkable in that it was the first use of reflected light as an illumination source. Unfortunately he was censured for his ingenuity since the intended use of the instrument was considered an unnatural act under contemporary mores. Bozzini died at the age of 35 after contracting typhus probably contracted during house calls [9].

Pierre Segalas (France) also reported upon the use of candles and a cone-shaped silver cube to reflect light into the urinary bladder. His refined urethroscope in 1826 was primarily used in female patients which he called “urethro-cystique” [32]. John Fischer from Boston also developed a functional but cumbersome elongated and angled speculum [33]. Anton J. Desormeaux (France) presented the first serviceable endoscope to the Academy of Paris in 1853. The light source for this instrument consisted of a reflected lamp fueled with a mixture of alcohol and turpentine, with which he performed numerous investigations of the urethra and bladder [34].

Other external illumination sources followed; however the next major innovation was to be the development of an independent light source that could be transported into the body cavity being inspected. Julius Bruck (Poland) in 1860 examined the mouth using illumination provided by a platinum wire loop heated by an electric current within a water jacket [35]. This was the first galvanic endoscope and preceded the invention of Edison’s filament globe by 20 years. There were numerous other descriptions throughout the remainder of the late nineteenth century on open tube endoscopy procedures including Kussmaul’s description of removal of a foreign body from the esophagus using reflected sunlight. Killian in 1898 employed a tube endoscope with illumination via a reflecting head mirror with the assistance of topical cocaine to inspect the bronchus [36].

Maximilian Nitze was a general practitioner who thought that if an instrument could be introduced with ease, minimal pain, and relative safety the endoscopes must be smaller [37]. His idea was to place lenses into the tubes at prescribed distances to focus the image at an ocular. In addition, his early version used a platinum wire in a glass jacket with water cooling methods. He began clinical investigations with this cystoscope in 1877. By 1879, Nitze’s design team was aware of Edison’s invention of the filament globe and they immediately miniaturized it to fit into the tip of the cystoscopes. The first actual use of the Edison incandescent lamp for cystoscopic application was by Newman (Glasgow, 1883), followed by Nitze (1887), Leiter (1887), and Dittel (1887) [38]. Now the pathway to the ureter and visualization of its pathology became possible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree