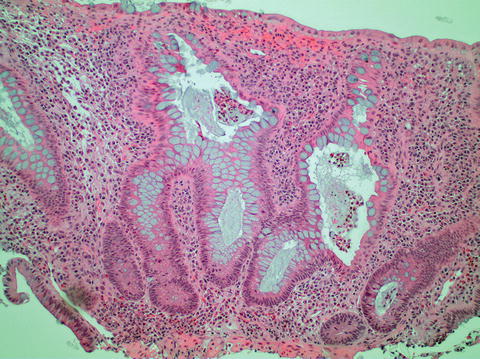

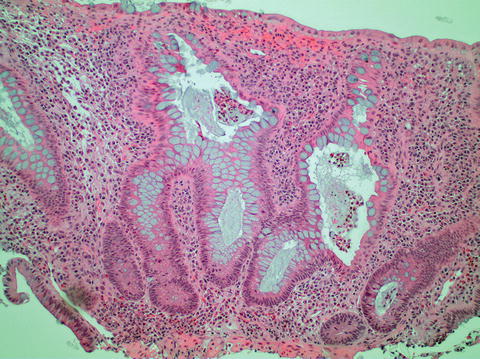

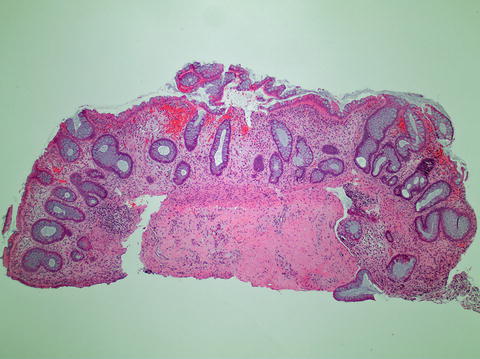

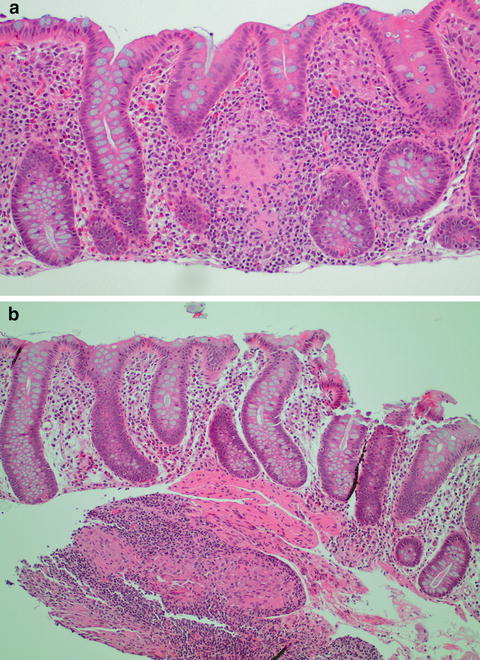

Fig. 11.1

(a) Normal right colon mucosa with increased lamina propria cellularity. (b) Normal left colon mucosa

Lymphocytes are normally present as scattered single cells in the lamina propria of the colon. However, mucosal lymphoid aggregates can also occasionally be seen. Additionally, rare intraepithelial lymphocytes can also be present in colonic epithelium, with 5 lymphocytes per 100 enterocytes being considered normal [1]. Slightly increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes are common around lymphoid aggregates.

Crypt Architecture

In a well-oriented biopsy with normal crypt architecture, the crypts are evenly spaced with bases that abut the muscularis mucosa and extend perpendicularly to the surface with an appearance that has been described to be akin to “a row of test tubes.” In the rectum, mild architectural distortion is acceptable, with slight irregularity in crypt spacing and mild shortening of crypts.

Epithelial Cell Components

Paneth cells are normally present proximal to the splenic flexure; however, when present distal to this anatomic site, Paneth cell metaplasia can be a sign of chronic injury.

Histologic Features of Colitis

Active colitis is considered to be present when there is neutrophilic inflammation and epithelial injury. There may be neutrophilic cryptitis, crypt abscesses, erosions, or ulceration. However, the presence of rare intraepithelial neutrophils (particularly in a superficial location) can be secondary to bowel preparation [2].

Histologic Features of Chronic Colitis

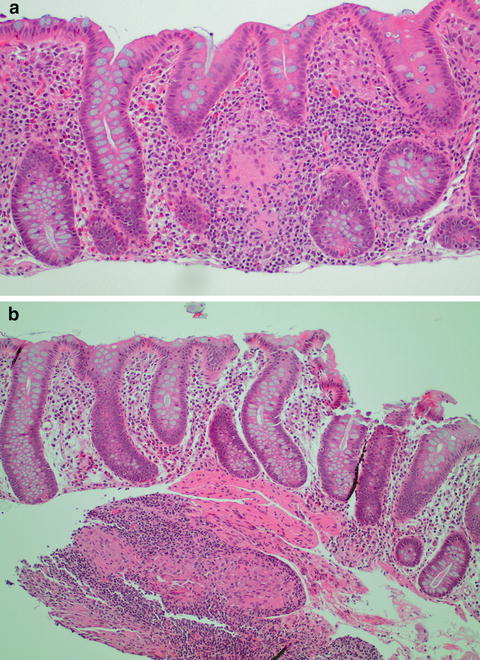

When colitis persists, the chronicity of the inflammatory process is associated with other histologic abnormalities. As inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is considered a chronic disease process, histologic features of chronicity are considered supportive evidence of IBD and can be helpful in distinguishing between IBD and cases of acute self-limited colitis (which typically resolve in less than a month). An example of chronic active colitis is seen in Fig. 11.2.

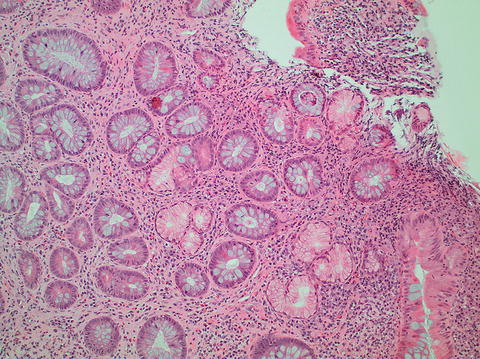

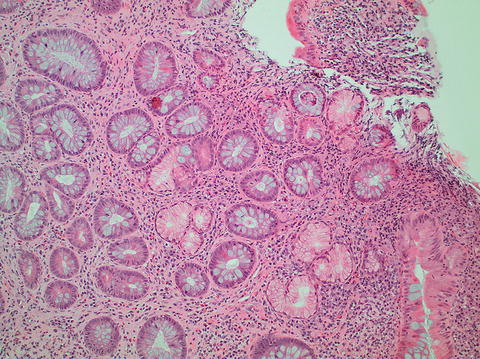

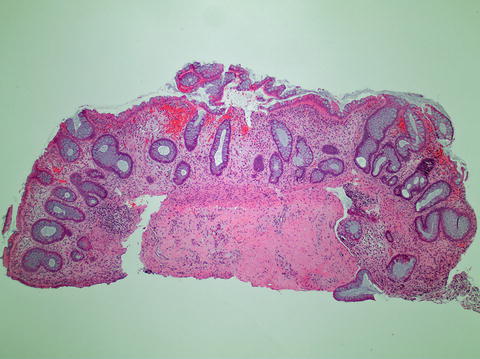

Fig. 11.2

Chronic active colitis with neutrophilic crypt abscesses, crypt architectural distortion, and basal lymphoplasmacytosis

Mucosal Inflammatory Cells

Changes of the inflammatory cell infiltrate in the lamina propria can be one of the most reliable features of chronic colitis. Increased density of lamina propria inflammation is often seen in both acute self-limited colitis and in chronic colitis. Basal plasmacytosis, a term used to describe the presence of plasma cells at the base of the mucosa that can separate the crypt bases from the muscularis mucosa, is considered one of the most specific features of chronicity. Basally located lymphoid aggregates are also considered abnormal and can be seen in chronic colitis, but are often difficult to objectively identify. Multinucleated giant cells and granulomata are not normal components of the mucosa, and their presence can raise the possibility of Crohn’s disease, although their presence is not pathognomonic.

Crypt Architecture

Changes in crypt architecture indicating chronicity include crypt branching and crypt atrophy (shortened crypts that do not reach the muscularis mucosa, and irregular spacing between crypts). These alterations in crypt architecture are thought to reflect crypt regeneration after mucosal injury. Irregularity of the mucosal surface can also be seen in chronic colitis. There is often dilation of the crypt lumens towards the surface with crypt separation that results in a villiform, undulating mucosal surface.

Epithelial Cell Components

Epithelial cell metaplasia including Paneth cell metaplasia and pyloric gland metaplasia (seen in Fig. 11.3) can also be associated with chronic colitis.

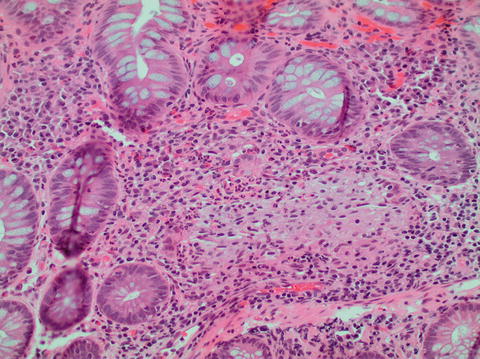

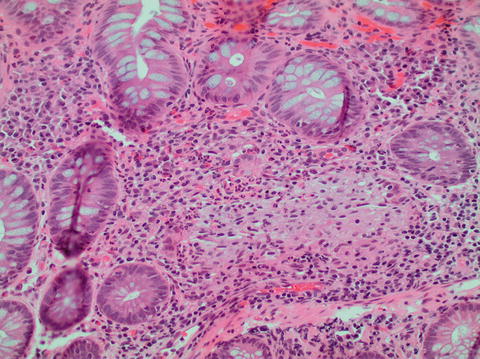

Fig. 11.3

Pyloric gland metaplasia

Reliability of Histologic Findings as a Marker of Chronicity

Although many of the features of chronicity previously listed are useful in differentiating between acute self-limited colitis and IBD, the exact degree of histologic change and number of features of chronicity required for a diagnosis of IBD are not well defined. Several studies have found that the presence of (1) crypt architectural distortion and (2) basal plasmacytosis are the most reliable in distinguishing between IBD and acute self-limited colitis [3–6].

However, it should be remembered that features of chronic mucosal injury are not specific to IBD. Chronic injury secondary to etiologies other than inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., ischemic injury, radiation, etc.) can occasionally have a similar histologic appearance (an example is seen in Fig. 11.4). A discussion of other histologic mimics of IBD is presented later in this chapter.

Fig. 11.4

Chronic ischemic colitis with architectural distortion

It should also be remembered that histologic features of chronicity may not be present at time of presentation. While basal plasmacytosis is a relatively early change and can be seen within the first 15 days of symptoms, crypt architectural abnormalities are not present until after 2 weeks of disease. In addition, on first presentation, the findings can be focal, with increased severity and prevalence over time [7]. Thus, a diagnosis of IBD always requires careful correlation of histologic findings with clinical findings.

Correlation of Endoscopic Appearance to Histologic Appearance in IBD Biopsies

Although endoscopic appearances often correlate well with histologic findings, correlation is not absolute. Lemmens et al. compared the endoscopic and histologic appearances of 131 patients with ulcerative colitis. The biopsies were scored using the Geboes and Riley histologic scoring system, and the endoscopic scoring was performed using the Mayo endoscopic subscore. Overall, although endoscopic and histologic scores correlated well with inactive and in severely active disease, there was not good correlation when disease activity fell between the two extremes [7–9].

In other studies that compared endoscopic appearances with histologic findings, although the bowel appeared endoscopically normal, histologic examination revealed persistent inflammatory activity. In a study of 797 biopsy sites from 41 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), Kleer et al. described a lack of endoscopic-histologic correlation in one-third of cases. In 25 % of the biopsies, an endoscopically normal appearing biopsy site showed chronic colitis histologically [10]. A subsequent study of 75 UC patients with endoscopically inactive disease showed histologic evidence of colitis in 40 % of patients [11]

In a study of both biopsy and colectomy specimens from 56 patients with ulcerative colitis, Joo and Odze found that an endoscopic appearance of rectal sparing concurred with the biopsy histologic features in approximately 80 % of patients. However, there was no statistical correlation between endoscopic appearance and the histologic findings in the resected colectomies [12].

Compared to ulcerative colitis, endoscopic and histologic appearances are often more difficult to correlate in Crohn’s disease (CD), where changes are patchy, and sampling error can be an issue.

Definition of Activity in IBD

In IBD, disease is often categorized as being either active, chronic active, or chronic inactive (quiescent). Active (or acute) colitis would be considered the presence of neutrophilic epithelial injury without features of chronicity. Mucosal biopsies with chronic active colitis would contain features of chronic mucosal injury as well as active epithelial injury. Chronic inactive colitis or quiescent colitis would be the term used when there are features of chronic mucosal injury without concurrent neutrophil mediated epithelial injury.

Grading Histologic Activity in IBD

During the evaluation of mucosal biopsies from patients with IBD, in addition to categorizing colitis as either chronic and/or active, it is recommended that histologic disease activity be graded. However, a single widely accepted grading system does not currently exist. Several different grading systems have been proposed, some of which were developed specifically for either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

In some systems [12–14], disease is first separated into various “phases” of disease (e.g., normal, chronic inactive/quiescent, and chronic active disease); then, if active disease is present, it is graded based on the presence or absence of neutrophilic cryptitis, crypt abscesses, surface ulceration/erosion, and amount of mucosa involved. For example, Joo and Odze used a five-tier grading system with 0 = normal mucosa, Grade 1 = chronic inactive colitis, Grade 2 = chronic colitis with mild activity, Grade 3 = chronic colitis with moderate activity, and Grade 4 = chronic colitis with severe activity [12].

A similar grading system put forth by Geboes et al. [8] incorporated both evidence of chronicity and progressively increasing active epithelial injury. In their system, biopsies were given a grade of 0 and/or 1 if they contained crypt architectural changes and chronic inflammatory infiltrates but no evidence of active epithelial injury. Biopsies were given grades ranging from 2 to 5 if they showed both chronic changes as well as neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation, crypt destruction, or surface erosion and ulceration of increasing severity.

In other grading systems, different histologic findings are each given a separate grade and a sum of all the grades are used as the final score. For example, a grading system put forth by Riley et al. [7] included the evaluation of six histologic features (neutrophilic inflammation in the lamina propria, crypt abscesses, mucin depletion, surface epithelial integrity, chronic inflammation in the lamina propria, and crypt architectural abnormalities) and each feature was graded on a four-tier system (none, mild, moderate, or severe).

At our institution we consider “mild” activity to be presence of neutrophilic cryptitis without the presence of crypt abscesses, “moderate” activity to be the presence of cryptitis and crypt abscesses, and “severe” activity would be used to describe the presence of marked neutrophilic inflammation with ulceration.

When tested, the reproducibility of scoring systems shows relatively good interobserver agreement. However, the number of these studies are relatively limited. Scoring systems based on phases of activity as well as scoring systems based on the sum of all histologic findings appear to show relatively similar reproducibility. Odze et al. [15] used a histologic disease activity scoring system to quantitate the effect of topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) on the histologic appearance of mucosal biopsies of UC patients. Biopsies were given a histologic score based on the presence or absence of features of chronicity (abnormal crypt architecture, villiform surface contour, mixed inflammation in the lamina propria, basally located plasma cells, basally located lymphoid aggregates, and Paneth cell metaplasia) along with the presence or absence of neutrophilic inflammation. They found that there was only minor interobserver variation occurring in less than 10 % of their biopsy samples. Interobserver variation was also measured in the study by Riley et al. [7] using the scoring system described previously. They found that 82 % of their biopsies were given the same grade by the two reviewing pathologists, and that scoring differed by more than one grade in only 2 % of the sections.

Histologic Activity and Risk of Progression to Neoplasia

There is some evidence that there is an association between increased histologic inflammation and increased risk of progression to neoplasia in patients with IBD. In a case–control study of 68 patients with ulcerative colitis who developed colorectal neoplasia and their matched controls (136 patients total), Rutter et al. [16] found that there was a significant correlation between endoscopic and histologic inflammation and risk of progression to colorectal neoplasia. Similar results were reported by Rubin et al. [17]. Biopsies from 141 UC patients without colorectal neoplasia and 59 UC patients who developed colorectal neoplasia were scored using a six-tier histologic activity index. In univariate analysis, they determined that there was a positive association of increased histologic inflammation with development of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Finally, in a cohort study of 418 patients with ulcerative colitis, Gupta et al. [18] found a significant relationship between increased histologic inflammation and subsequent development of high-grade dysplasia or colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Histologic Activity as Predictor of Clinical Relapse

Evidence of histologic inflammation may indicate risk of clinical relapse. As mentioned previously, even in endoscopically normal appearing mucosa, there can be evidence of persistent inflammation on histologic examination. Several studies suggest that the finding of histologic abnormalities in endoscopically normal appearing mucosa correlates with earlier relapse. In a 1-year prospective study of 74 patients with clinically and endoscopically inactive ulcerative colitis, Bitton et al. [19] determined that the presence of basal plasmacytosis on histologic examination of mucosal biopsies was an independent predictor of earlier relapse. Similarly, in a cohort study of 75 UC patients with endoscopically inactive disease, Bessissow et al. [11] found that that the presence of basal plasmacytosis was predictive of a clinical relapse. Interestingly, although 40 % of their cases contained active histologic inflammation with a Geboes score ≥ 3.1 (“presence of epithelial neutrophils with or without evidence of crypt destruction or erosions”) this was not identified as an independent predictor of relapse. In contrast, Riley et al. [7] found that the presence of neutrophilic cryptitis or crypt abscesses in biopsies of endoscopically normal appearing mucosa correlated with relapse. However, the presence of a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria did not appear to correlate with relapse.

Histologic Activity and Treatment Goals

Histologic disease activity can also be used as a tool for determination of treatment efficacy, and it has been proposed that resolution of histologic inflammation should serve as a possible therapeutic goal [20]. However, several issues still exist that would make this difficult. First, it is not clear exactly which histologic findings should be considered a goal for therapy. Possible targets would include resolution of neutrophilic inflammation versus reversion of the mucosa to a normal histologic appearance. Second, it is likely that defining histopathologic therapeutic targets for ulcerative colitis will need to be determined separately from Crohn’s disease. Although mucosal biopsies may accurately reflect disease in UC, because of the patchy disease involvement of Crohn’s disease and the transmural nature of the disease, limitations of sampling may also limit the ability of histopathologic analysis of endoscopic biopsy samples to serve as a treatment guide.

Histopathologic Features of Ulcerative Colitis

Classically, ulcerative colitis involves the rectum with continuous extension of disease proximally. On gross-examination “skip-areas” of intervening normal mucosa are not present. Examination of biopsy specimens also reflects the continuous nature of the disease, with a relatively uniform distribution of histologic changes between biopsy fragments.

Histologic findings in ulcerative colitis reflect changes of chronic colitis. There is increased inflammation in the lamina propria, present as a diffuse increase in lamina propria cellularity as well as basal plasmacytosis. Crypt architectural abnormality with crypt branching, crypt foreshortening (or crypt atrophy), and villous architecture is often present (17–30 %) and is seen more commonly in ulcerative colitis than Crohn’s disease (12 %) [2, 5]. Other features of chronicity, such as Paneth cell metaplasia, can be present. When there is active disease, neutrophilic cryptitis is more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease [2].

When resection specimens, rather than biopsies, are evaluated, the mural extent of inflammatory changes can be assessed. In ulcerative colitis, inflammation is typically limited to the mucosa and superficial submucosa. When present, ulceration is usually non-fissuring and does not extend deeper than the submucosa, although some studies have shown that shallow fissuring ulcers can occasionally be seen [21].

Granulomatous Reaction to Ruptured Crypts

Of patients with Crohn’s disease, 30–50 % have granulomata in the colonic mucosa. Although this is a useful diagnostic feature in distinguishing Crohn’s colitis from ulcerative colitis, the presence of granulomata are not absolutely specific for Crohn’s disease. The presence of granulomatous or giant cell reaction to ruptured crypts, also termed mucin granulomas or “cryptolytic” granulomas, can occur in ulcerative colitis as well as in other colitides such as infectious colitis, diverticular colitis, and diversion colitis [22–25]. In ulcerative colitis, it is thought that crypt rupture and release of mucin and crypt luminal contents into the lamina propria can induce a histiocytic, giant cell, and granulomatous inflammatory reaction (Fig. 11.5). In a study of 29 patients whose mucosal biopsy specimens contained granulomas or giant cells, Mahadeva et al. [22] found that 10 of the patients could be given a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis based on the histologic findings in prior and subsequent biopsies and 90 % of these patients also had a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis based on clinical findings. Thus, granulomatous reaction to crypt rupture does not reliably distinguish between Crohn’s disease and other colitides [25]. However, careful examination of multiple levels may be required to determine whether granulomas are associated with crypt injury. In the study by Mahadeva et al., the patient whose histologic findings were suggestive of ulcerative colitis, but whose clinical features did not appear consistent with this diagnosis, had a solitary granuloma that did not appear associated with crypt injury [22].

Fig. 11.5

Ulcerative colitis with crypt rupture granuloma

Unusual Variants of Ulcerative Colitis

Although the classic pattern of ulcerative colitis involves the contiguous involvement of the rectum and colon, the evaluating pathologist should be aware of exceptions to this rule in which an unusual, or Crohn’s-like, disease distribution can be seen in patients with UC (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1

Unusual patterns of disease in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

Ulcerative colitis |

Patchy disease distribution |

Treatment effect |

“Patch” of cecal or ascending colon inflammation |

Peri-appendiceal inflammation present as a skip lesion |

Initial presentation in pediatric patients |

Ileal inflammation in “backwash” ileitis |

Upper GI tract involvement such as diffuse duodenitis |

Crohn’s disease |

Crohn’s colitis with mucosa only involvement |

Treatment Effects in UC

Patients with longstanding UC may show rectal sparing and a patchy distribution of disease, with normalization of the mucosa on both endoscopic and histologic examination [4, 10]. Reversion of the mucosa to a normal morphologic and histologic appearance can be enhanced by treatment. The 1993 study by Odze et al. [15] found that 36 % of UC patients who were treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid and 12 % of controls showed rectal sparing on post-treatment biopsies. In subsequent studies, other groups reported that 30 % to 59 % of UC patients showed either rectal sparing or patchy disease on follow-up biopsies [26, 27]. Kleer et al. [10] examined sequential biopsy specimens from 41 patients with UC. The histologic appearance of biopsy specimens reverted to normal in 22 of the 41 patients. Thus, a normal appearing biopsy specimen in a patient with treated or longstanding ulcerative colitis should not be misinterpreted as evidence of Crohn’s disease. In addition, because normalization of histologic findings can occur in previously treated patients, determination of the distribution of colitis is best made on pre-treatment biopsies.

Pediatric UC Patients

Unlike adult UC patients, pediatric patients may present with relative or complete rectal sparing or with only patchy disease involvement. Markowitz et al. [28] analyzed 17 pediatric patients without a history of treatment and found that 42 % of patients had only patchy rectal disease or a normal rectum. A subsequent study by Washington et al. [29] reported that only 32 % of children (in contrast to 53 % of adults) presented with diffuse rectal disease. Glickman et al. [30] evaluated biopsies from 73 pediatric patients and 38 adult patients and showed that 30 % of children had either only patchy inflammation in the rectum or complete rectal sparing at time of presentation. In this study only a single adult had relative rectal sparing and no adult patients showed complete rectal sparing. In addition, 21 % of the pediatric patients had only patchy involvement by inflammation, while no adult patients had this finding.

The difference in disease distribution and the severity of inflammation in pediatric patients may be more common in younger patients. Robert et al. [31] studied biopsies from 15 pediatric patients and 25 adult patients at time of presentation, and found that there were fewer histologic features of active and chronic disease in pediatric patients, but that this difference was more common in patients younger than 10 years.

Cecal, Ascending Colon, and Appendiceal Involvement in UC

Even in patients with left-sided UC, a “patch” of endoscopic and histologic disease activity can occasionally be seen in the cecum and right colon, and can even be present at initial presentation [32–35]. In a prospective study, Ladefoged et al. [33] discovered endoscopic evidence of periappendiceal inflammation in 27 % of patients with UC without evidence of cecal or ascending colon involvement. D’Haens et al. [34] evaluated both the endosocopic appearance and colonic resection specimens from 20 patients with UC and found that 75 % of patients with left-sided disease had an area of cecal involvement, always including the area around the appendiceal orifice, that was separated by an area of uninvolved mucosa. In a case control study by Mutinga et al [35], 12 patients with left-sided UC and patchy right colonic inflammation were compared to 127 case controls with only left-sided disease. There was no significant difference in age, gender, extraintestinal involvement, progression to pancolitis, or severity of disease. In follow-up, none of the patients developed features of Crohn’s disease.

Discontiguous Involvement of the Appendix

Appendiceal disease, unassociated with periappendiceal or cecal involvement, has been reported in 12-87 % of patients with UC [36–41]. In 1990, Davison et al. [38] reported that discontinuous appendiceal involvement was present in 21 % of their UC patients. However, a subsequent study by Goldblum and Appelman [39] found that appendiceal involvement in UC was present only if contiguous cecal involvement was present. Still, subsequent studies have described discontinuous appendiceal “skip” lesions in UC patients. Groisman et al. [40] examined 160 consecutive colectomy specimens from adult and pediatric UC patients. Ulcerative appendicitis was identified in 82 of 94 cases of pancolitis, as well as in 12 of 14 cases where disease involvement was otherwise only present distal to the hepatic flexure. In another retrospective study, Kroft et al. [41] evaluated 39 resection specimens, and found that 15 % of the examined specimens showed appendiceal disease with normal or nonspecific cecal histologic findings.

Thus, focal cecal, ascending colon, or appendiceal disease activity, present as apparent “skip” lesions, should not completely exclude a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis.

Ileitis in UC: Backwash Ileitis

Although ulcerative colitis is classically defined as an inflammatory process of the colon, ileal inflammation has been described in a subset of patients with ulcerative colitis. It has been presumed that the mechanism of distal ileal inflammation in ulcerative colitis is pan-colitic associated reflux of colonic contents into the ileum through an incompetent ileocecal valve with subsequent ileal inflammation, or “backwash” ileitis. In contrast to the more extensive ileal involvement of Crohn’s disease, ileal inflammation in ulcerative colitis is generally limited to only a few centimeters proximal to the ileocecal valve. In addition, other features of Crohn’s disease such as granulomas, fissuring ulcers, and transmural inflammation are not seen.

To better outline the histopathologic features of backwash ileitis, Haskell et al. [42] examined colectomy specimens from 200 UC patients. Ileitis was present in 17 % of the cases and the inflammation was generally limited to the distal 1 cm of ileum. The histologic features of the ileal inflammation in these cases consisted of mild, patchy neutrophilic inflammation in the lamina propria, focal cryptitis or crypt abscesses, and patchy villous atrophy and regenerative changes.

Backwash ileitis may be becoming less common with current treatment regimens. To see if the features of backwash ileitis have changed over time, Goldstein and Dulai [42] examined 250 UC colectomy specimens from three different time periods (1960 through 1979, 1980 through 1997, and 1998 though 2004). Overall, 82 (32.8 %) of the cases showed backwash ileitis. However, there was a decrease in the prevalence of both cecal activity and backwash ileitis over time. Although 28 % of cases resected in 1960–1979 had only mild or quiescent cecal disease, 44 % of cases from 1998 to 2004 showed mild cecal disease and 54 % of cases from 1998 to 2004 showed quiescent colitis. There was correspondingly less backwash ileitis seen in the more recent resection specimens. While 72 % of cases from 1960 to 1979 showed moderate to marked backwash ileitis, no cases from 1998 to 2004 contained moderate to marked backwash ileitis and only 1 case had mild backwash ileitis.

Upper GI Tract Involvement

Although upper GI tract (esophagus, stomach, duodenum) involvement is classically associated with Crohn’s disease, rare cases of gastric and/or duodenal involvement have been described in patients with ulcerative colitis. In particular, upper GI tract involvement has been documented in several pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis [43, 44]. Kaufman et al. [43] described five children with pancolitis without granulomata who underwent subtotal colectomy, all of whom had chronic active gastritis and some of whom had duodenitis. In subsequent follow-up, none of these patients developed Crohn’s disease. In a study comparing 14 children with ulcerative colitis to 28 children with Crohn’s disease, Tobin et al. [44] found that a significant number of pediatric patients also showed upper GI tract inflammation (50 % had esophagitis, 69 % had gastritis, and 23 % had duodenitis).

Interestingly, studies seem to indicate that, in UC patients with upper GI tract disease, the duodenum may be the most common site of involvement. Valdez et al. [45] described four patients with ulcerative colitis who also exhibited diffuse duodenitis. More recently, in a study comparing esophageal, gastric, and duodenal biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis to matched controls, Lin et al. found diffuse chronic duodenitis was unique to the ulcerative colitis patients and was present in 10 % of the duodenal biopsies from ulcerative colitis patients. Several cases of duodenitis in UC parients have also been described in the Japanese literature [46, 47].

Histopathologic Features of Crohn’s Disease

In patients with Crohn’s disease, 30–40 % will have only small bowel involvement, 30–40 % will have ileocolonic disease, and 10–20 % will have colonic involvement only. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s colitis typically shows areas of segmental involvement with intervening areas of uninvolved colon (skip lesions). In addition, unlike ulcerative colitis, many patients with Crohn’s disease will have complete or relative rectal sparing.

On histologic examination, Crohn’s colitis shows changes of chronic injury with increased inflammation in the lamina propria and basal plasmacytosis. However, inflammation can be heterogeneous, both between biopsy fragments as well as within a single biopsy fragment. Other features of chronicity such as crypt architectural abnormality, Paneth cell and pyloric (mucous) cell metaplasia may also be present and show heterogeneity in distribution. Similarly, neutrophilic epithelial injury can be variable between biopsy specimens. Occasionally, injured and inflamed crypts can be seen immediately adjacent to normal appearing crypts. This patchy distribution of chronic changes and active epithelial injury can be helpful in favoring a diagnosis of Crohn’s colitis over ulcerative colitis [48, 49].

Two types of ulceration are also thought to be relatively characteristic of Crohn’s disease: aphthous ulcers and fissuring ulcers. Aphthous ulcers are seen as small, shallow areas of superficial erosion and neutrophilic inflammation overlying lymphoid aggregates. Fissuring ulcers are deep, “knife-like” ulcers that extend deep into the bowel wall. Although they are not absolutely specific for Crohn’s colitis, their presence would favor a diagnosis of Crohn’s colitis over ulcerative colitis. However, the presence of fissuring ulceration is determined only on the examination of resection specimens, and cannot be appreciated in mucosal biopsies.

As mentioned previously, 30–50 % of patients with Crohn’s disease have granulomas in the colonic mucosa. The presence of non-cryptolytic granulomas is considered a relatively specific feature of Crohn’s disease that can help distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Granulomas in Crohn’s disease can be present as pericryptal granulomas (Fig. 11.6a) not associated with crypt rupture or mucin extravasation as well as well-formed non-necrotizing granulomata in the submucosa (Fig. 11.6b).

Fig. 11.6

(a) Crohn’s colitis with mucosal granuloma. (b) Crohn’s colitis with submucosal granuloma

When resection specimens are assessed, the transmural inflammation of Crohn’s disease can be appreciated. Grossly, serosal inflammation may result in “fat wrapping” or “creeping fat” with extension of the mesenteric adipose tissue onto the anti-mesenteric surfaces of the colon. Histologically, the transmural inflammation of Crohn’s disease can be seen in the form of transmural lymphoid aggregates, particularly lymphoid aggregates away from areas of ulceration. As mentioned, deep fissuring ulcers extending beyond 50 % of the thickness of the muscularis propria are also more commonly seen in CD. Other evidence of the transmural inflammatory pattern of Crohn’s disease would include the presence of fibrostenotic lesions, and the presence of fistula and sinus tracts. Granulomas and patchy inflammation in biopsy specimens, and evidence of transmural inflammation would all support a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease over ulcerative colitis (outlined in Table 11.2).

Table 11.2

Histologic findings helpful in distinguishing between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

Histologic finding | Comment |

|---|---|

Favoring ulcerative colitis | |

Diffuse distribution of disease | Most reliable in pre-treatment biopsies of adult patients |

Favoring crohn’s disease | |

Patchy inflammation with variation within and between biopsy fragments

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |