Symptom

Differential diagnoses

Pain

Thrombosed hemorrhoids, fissure, abscess, fistula, pruritus, anorectal Crohn’s disease, anismus, abscess

Bleeding

Internal or external hemorrhoids, fissure, fistula, hypertrophic papilla, polyps, anal or colorectal cancer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, infectious colitis, draining thrombosed hemorrhoids, rectal prolapse

Pruritis

Prolapsing hemorrhoids, fistula, incontinence, anal condylomata, rectal prolapse, pruritus ani, anal papilla, dermatitis, dietary causes

Mass

Thrombosed or prolapsed hemorrhoids, abscess, anal cancer, prolapsing polyp or papilla, skin tags, prolapsing tumor, rectal prolapse, condylomata

Evaluation

History

Document the patient’s bowel habits, including constipation, diarrhea, urgency, frequency, and changes in bowel habits. A prospectively maintained bowel diary may be helpful.

History can help differentiate hemorrhoids from other anal pathology. It can also elicit “red flag” symptoms such as bleeding or change in bowel habits that may be indicative of malignancy.

Dietary history is included particularly focusing on fiber and fluid intake with attention to foods that cause diarrhea or constipation.

Changes in bowel and diet habits due to an acute illness or travel should be noted.

Physical Examination

Includes a general exam that focuses on liver disease, COPD, or coagulopathy.

The abdominal exam will focus on signs of constipation.

An anal exam may be embarrassing and same gender chaperone should be offered to be in the room to help relax the patient. Also reassure your patient and communicate what you will be doing.

The prone jackknife position allows for maximal anal exposure. If impractical (too obese, pregnant, or orthopedic issues), then left lateral or lithotomy position is chosen.

Describe anatomy and pathology in anatomical terms (left, right, anterior, posterior), and avoid using the position of the clock (patient’s position may change).

Inspect the anoderm and sacrococcygeal region. Identify external hemorrhoids, skin tags, prolapsing internal hemorrhoids, rectal prolapse, excoriated skin, fissures, fistulas, abscesses, anal cancer, thrombosed external hemorrhoids, rashes, or dermatitis.

Palpate the area to assess induration, tenderness, masses, or thrombus in external hemorrhoids.

Use the digital exam to assess sphincter tone (both rest and squeeze), and identify masses, abscesses, and localized pain.

The degree of prolapse is examined by asking the patient to strain. If there is any concern, an evaluation with the patient on a commode (which is a more physiologic situation) may be required.

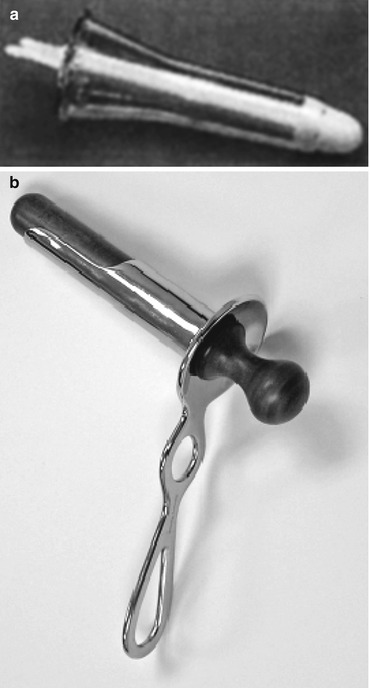

Anoscopy is performed using one of the several types of anoscopes available (Fig. 11.1).

Fig. 11.1

(a) a clear plastic anoscope and (b) Ives-Fansler anoscope

Rigid or flexible proctoscopy evaluates the rectum for inflammation.

Colonoscopy or barium enema is ordered if red flag symptoms are present. These are considered in the context of the patient’s age, personal and family history of colorectal pathology, duration of symptoms, and nature of bleeding. Due to concerns of inflaming hemorrhoids with a bowel preparation, treatment of the hemorrhoids for several weeks to months may be reasonable prior to a more in-depth colonic evaluation.

Treatment

Control of symptoms is the primary treatment goal.

Reassure patient that hemorrhoids are normal components of human anatomy and removal of all hemorrhoid tissue is not necessary.

Treatment is categorized into three groups:

Medical Management (Dietary and Behavioral Therapies)

Modify stool through increased dietary fiber (25 g/day for women and 38 g/day for men) and increased water intake (64 oz daily).

Encourage regular sleep/wake cycle and exercise to maintain regular bowel habits.

Add bulk-forming agents such as psyllium to modify quality of stool (Table 11.2). Taken with oral fluid, the goal is to add moisture and soften stools. Optimally, patients should ingest supplements in the morning so fluid can be consumed throughout the day to hydrate the supplements. If needed (inadequate stool mixing), divide doses throughout the day. Long-term compliance may be difficult due to poor palatability, bloating, excessive flatus, or crampy abdominal pain. Start at a low dose and titrate up for the desired effect to minimize side effects.

Table 11.2

Fiber supplements

Fiber supplement

Brand name products

Psyllium

Metamucil, Konsyl, Fiberall, Hydrocil, Perdiem, Serutan

Methylcellulose

Citrucel

Calcium polycarbophil

FiberCon, Fiber-Lax, Equalactin, Mitrolan

Wheat dextrin

Benefiber

Inulin

FiberChoice

Stool softeners (docusate), lubricants (mineral oil), and laxatives (hyperosmolar [polyethylene glycol], saline [magnesium citrate], or stimulant [senna or bisacodyl]) are used to treat constipation. Transition to fiber and stool softeners as quickly as feasible. Goal is a bulky but soft stool that is easy to pass.

Diarrhea may require additional evaluation including diet recommendations to increase fiber and reduce fat consumption, along with assessment of caffeine intake, alcohol intake, and irregular sleep/wake cycle which can all contribute to diarrhea. Profound or bloody diarrhea needs further evaluation with stool cultures, fecal fat analysis, and endoscopy. Loose stools can be treated with fiber supplementation that is titrated according to the patient’s symptoms.

The trial of increased fiber should be from 4 to 6 weeks followed by reevaluation of symptoms. The goal of medical management is symptom control. The appearance of the hemorrhoids may not change.

Toileting Behavior

Patients should spend only 3–5 min on toilet. Do not read on toilet.

Patients that cannot avoid excessive straining or require >30 min on the commode to evacuate stool should be evaluated for a pelvic floor disorder.

Avoid compulsive wiping which can lead to local trauma, contribute to inflammation from internal hemorrhoids, increase bleeding from external skin, and worsen pruritus. Use premoistened wipes, i.e. witch hazel, but avoid those with alcohol.

Sitz Baths

Use warm, approximately 40 °C water (without additives such as salt or oils), in a bathtub or portable device.

Limit duration to 15 min.

This treatment can provide relief of pain, itching, and burning and may aid hygiene (particularly after bowel movements).

May alleviate sphincter and pelvic floor muscle spasms.

Limited objective evidence regarding the use of sitz baths, but low cost and low risk, makes this an attractive treatment.

Medications

Topical medications have little objective evidence to support firm recommendations, but since they are so commonly used by patients to self-medicate themselves, surgeons need to be familiar with them. Many employ a combination of agents.

Local anesthetics may provide temporary relief of pain, itching, and burning. The medication delivery mechanism may cause local irritation. Some contain vasoconstricting agents in an effort to reduce swelling.

Barrier protectants prevent skin irritation by eliminating contact of mucous and stool with the skin.

Astringents clean and dry skin.

Analgesics sooth the skin.

Corticosteroids relieve perianal inflammation. Prolonged use may thin the skin.

Suppositories do not typically remain localized in the anal canal. However, they may provide indirect relief by delivering the medication to the rectum and anal skin. Suppositories frequently contain a combination of medicating agents.

Phlebotonics

These are a heterogeneous collection of substances used to treat many vascular conditions including hemorrhoids purportedly by improving venous flow, improving venous tone, stabilizing capillary permeability, and increasing lymphatic drainage.

Safety concerns with some phlebotonics include flavonoids that can cause GI side effects and calcium dobesilate which can cause agranulocytosis.

Citrus bioflavonoids are used in Europe. Commercially available nutritional supplements can contain diosmin and patients can obtain these.

Calcium dobesilate is a synthetic product which can stabilize capillary permeability, decrease platelet aggregation, and improve lymphatic transport. In a randomized trial comparing this to fiber, patients significantly improved after 2 weeks using calcium dobesilate.

Meta-analysis of 14 trials showed that flavonoids appear to give a beneficial effect.

Office-Based Procedures

Many office-based treatments are available and choice depends on surgeon experience, patient preference, availability of equipment, and the medical status of patient.

All techniques are directed at internal hemorrhoids that lack somatic innervation allowing these treatments to be applied proximal to the dentate line.

Rubber Band Ligation

Most common office procedure to treat internal hemorrhoids due to its efficiency, safety, and cost-effectiveness.

A small rubber band is applied at the apex and fixes the pedicle into its normal anatomical position. Ischemia causes hemorrhoids to shrink which corrects prolapse and improves venous drainage.

No bowel prep is needed, but an enema may improve visualization. Ideally, the patient is positioned in prone jackknife position, but can be in left lateral position. Rarely, if the patient cannot tolerate a full anoscopic exam, sedation in a monitored setting may be needed. Additionally, a bright light for viewing the anal canal and an assistant are usually required.

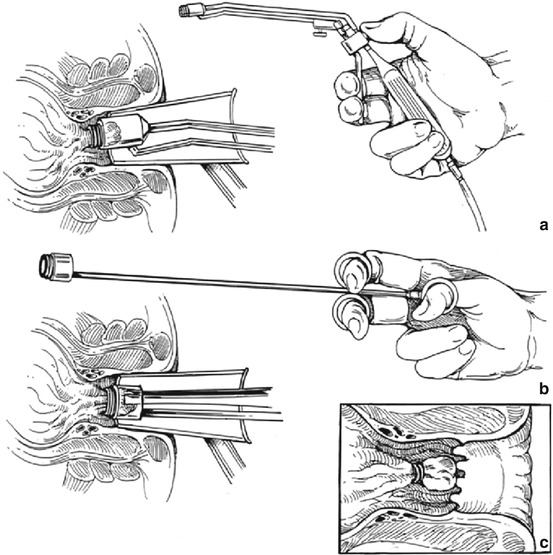

Using a grasping instrument (McGivney-type ligator or a variation), the apex of the tissue, approximately 2 cm proximal to the dentate line, is grasped and brought into the barrel (Fig. 11.2). The band can then be deployed from the end of the barrel. The band causes ischemia of the tissue it contains which will slough in 5–7 days. This creates an ulcer and inflammatory response. As this heals, fibrosis develops to secure the rectal mucosa to the sphincter.

Fig. 11.2

Rubber banding an internal hemorrhoid. (a) The internal hemorrhoid is teased into the barrel of the ligating gun with a McGown suction ligator or (b) a McGivney-type ligator. (c) The apex of the banded hemorrhoid is well above the dentate line in order to minimize pain (Reprinted from Beck D, Wexner S. Fundamentals of Anorectal surgery, 2nd ed. Copyright 1998, with permission from David Beck, MD)

Another type of ligator uses suction to draw the tissue into the barrel (McGown-type suction ligator). Since the ligator can be positioned and activated with the same hand, it leaves the other available to position the anoscope (versus the grasping ligator that requires two hands to deploy).

The endoscopic variceal ligator (used by gastroenterologists for bleeding esophageal varices) can be used with a flexible endoscope to band internal hemorrhoids.

Two disposable instruments have been developed for rubber band ligation. One is a suction device with four preloaded rubber bands (ShortShot®) (Fig. 11.3). The other disposable ligator (O’Regan ligating system, Fig. 11.4) uses a syringe type of device, which creates negative pressure to draw tissue into the device, and the band is deployed with a thumb trigger.