Hemorrhoids

Marvin L. Corman

And the men that died not were smitten with the emerods; and the cry of the city went up to heaven.

—1 Samuel 5:12*

*It is always stimulating to receive comments from readers of prior editions, especially those that are not merely flattering but from which I may learn of mistakes and omissions. The following communication was received from Professor Samuel Argov in Haifa, Israel.

–MLC

I read the Bible in its original Hebrew, and, being a colorectal surgeon, I have investigated the story of the Holy Ark, the Philistines, and the Israelites, as narrated in Samuel 1, Chapters 5, 6. It would appear that the Philistines were struck by an epidemic which is almost certainly bubonic plague, caused by Yersinia pestis. As is well-known, the disease is transmitted by mice and rats through their fleas. The epidemic swept quickly through the population (Samuel 1, Chapters 5, 11, 12). It is difficult to conceive of an epidemic of hemorrhoids. The fact that the Philistines gave an offering of five golden mice implies that they knew the pathogenesis of the plague (Samuel 1, Chapter 6, verse 4). This confusion of interpretation arises from an early incorrect translation of the Hebrew word Tchorim by the vulgata and later copiers to mean hemorrhoids. In actuality, the original Hebrew word Tchorim meant a ball or bubo. The mistake was carried forward into modern Hebrew. Even today in Israel, everyone uses the biblical term for the wrong disease.

Hemorrhoid disease affects more than 1 million Americans per year.37 It has been estimated that over a period of 3 years, approximately 4.4% of the US population will have symptoms attributed to hemorrhoids.142 Although the condition is rarely life threatening, the complications of therapy can be. This fact led to the beatification of St. Fiachre, the patron saint of gardeners and hemorrhoid sufferers.239,269 From the patient’s perspective, the complaint of “hemorrhoids” simply represents the diagnosis for a host of anal problems, including itching, a lump, pain, swelling, bleeding, and protrusion. In most physicians’ office practices, it is as likely that an individual’s symptoms will be attributable to another cause as they are to hemorrhoids.

Hemorrhoid complaints are one of the most common afflictions of Western civilization. The problem can occur at any age and can affect both sexes. It has been estimated that at least 50% of individuals older than the age of 50 years have at some time experienced symptoms related to hemorrhoids. Johanson and Sonnenberg analyzed data from governmental sources and concluded that the prevalence rate in the United States is 4.4%.142 In their study, Whites were affected more frequently than African Americans, and there was an increased frequency in those of higher socioeconomic status. It is also more common in rural than in urban areas. Some reports have commented on the relative rarity of the condition in rural Africa.43

The following have been suggested as factors that contribute to the development of hemorrhoids:

Heredity

Anatomic features

Nutrition

Occupation

Climate

Psychological problems

Senility

Endocrine changes

Food and drugs

Infection

Pregnancy

Exercise

Coughing

Straining

Vomiting

Constrictive clothing

Burkitt and Graham-Stewart refute most of these concepts and provide their own theories of pathogenesis (see the following section).43 This report and those of others have clarified the anatomy and attempted to establish the etiology on a more scientific footing.

▶ ETIOLOGY AND ANATOMY

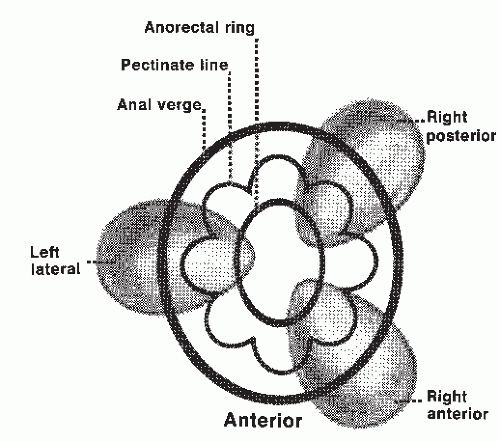

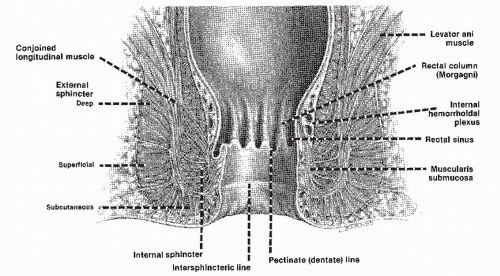

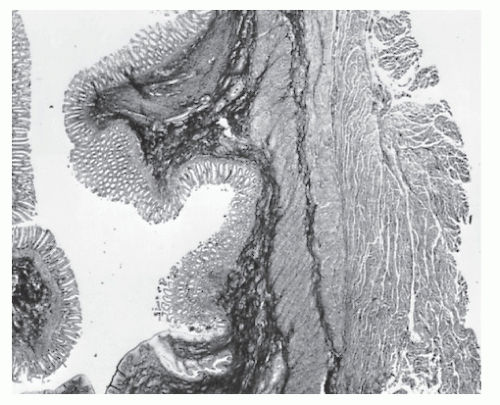

In 1975, Thomson published his master’s thesis based on anatomic and radiologic studies and introduced the term vascular cushions.290 According to this theory, the submucosa does not form a continuous ring of thickened tissue in the anal canal, but rather a discontinuous series of cushions; the three main cushions are found in the left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior positions (Figure 11-1). The submucosal layer of each of these thicker regions is rich with blood vessels and muscle fibers, the latter known as the muscularis submucosa (Figure 11-2).225,312 These fibers, arising from the internal sphincter and from the conjoined longitudinal muscle, are important in maintaining adherence of mucosal and submucosal tissues to the underlying internal sphincter and in supporting the blood vessels of the submucosa. It is postulated that the cushions, by filling with blood during the act of defecation, protect the anal canal from injury. The muscularis submucosa and its connective tissue fibers return the anal canal lining to its initial position after the temporary downward displacement that occurs during defecation.

The anal cushions receive their blood supply primarily from the terminal branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery (i.e., superior rectal artery) and, to a lesser extent, from branches of the middle hemorrhoidal arteries.32,225 These branches communicate with one another and with branches of the inferior hemorrhoidal arteries, which supply the lower portion of the anal canal. The superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal veins, which drain blood from the

tissues of the anal canal, correspond to each of the hemorrhoidal arteries.32,126,225

tissues of the anal canal, correspond to each of the hemorrhoidal arteries.32,126,225

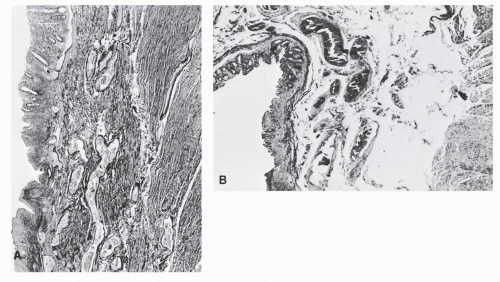

Anatomic studies by Haas and colleagues reveal that anchoring and supporting tissue deteriorates with aging, and that this phenomenon becomes apparent in the third decade of life (Figure 11-3).124 This ultimately produces venous distension, erosion, bleeding, and thrombosis (Figure 11-4).

The following are the four major theories regarding the causes of hemorrhoids.

1. Abnormal dilatation of the veins of the internal hemorrhoidal venous plexus, a network of the tributaries of the superior and middle hemorrhoidal veins43,223

2. Abnormal distension of the arteriovenous anastomoses, which are in the same location as the anal cushions126,127

4. Destruction of the anchoring connective tissue system124

Other theories have been proposed to explain abnormal distension of hemorrhoidal vessels. For example, hemorrhoids may be caused by a backflow of venous blood from transient increases in intra-abdominal pressure. It is this observation and the relative infrequency of the condition in rural Africa that caused Burkitt (see Biography, Chapter 27) and Graham-Stewart to assert the importance of crude fiber in the daily food intake to avoid straining with defecation.43 They even suggested that because Napoleon was troubled by hemorrhoids at Waterloo, the course of history could have been changed but for a few ounces of bran. However, others have called the presumption of causality between straining or constipation and hemorrhoids into question.142

Pressure exerted on the hemorrhoidal veins by a fetus explains the exacerbation of the condition in pregnant women.176,226 Engorgement of vessels may result from a defect in venous drainage, which, in turn, may be caused by failure of the internal sphincter to relax as it should during defecation. Vascular distension may be attributed to augmented arterial flow; this would account for why some with hemorrhoids feel additional discomfort after a heavy meal. More blood is delivered to the digestive system through the mesenteric artery, of which the superior hemorrhoidal artery is a branch.281 Hemorrhoids, however, are not varicose veins. They are structures that are normally present but do not produce symptoms until the fibromuscular supporting tissue above the cushions deteriorates.34 This permits the cushions to slide, engorge, prolapse, and bleed.

Hemorrhoids may be caused by more than one factor. Although some evidence suggests that hemorrhoids are familial, it is not known whether this is caused by hereditary influences (e.g., weak-walled veins, atrophied or weakened

fibrocollagenous supporting tissue) or environmental factors (e.g., family members may have similar dietary or bowel habits).

fibrocollagenous supporting tissue) or environmental factors (e.g., family members may have similar dietary or bowel habits).

Despite a vast literature on the subject of hemorrhoids, the pathogenesis and even the function of this tissue remain controversial. Furthermore, there still exists a difference of opinion as to the definition of hemorrhoidal disease. The high prevalence of anoscopic evidence of this pathologic entity and its problematic relationship to symptoms suggests that perhaps these findings may be more a consequence of the aging process than truly a disease entity.172

Wexner and Baig opine, however, that hemorrhoidal tissue performs three main functions besides that of the veins providing drainage of blood from the area.306 These functions theoretically include the following:

Maintenance of continence through the filling of the vascular cushions (15% to 20% of resting anal pressures)

“Protection” of the sphincter mechanism by providing a cushion

Augmentation of the anal closure mechanism306

Portal Hypertension and Rectal Varices

What is the relationship of hemorrhoids to portal hypertension? The most common manifestation of hemorrhage in patients with liver disease is upper gastrointestinal bleeding, not lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Numerous studies have failed to demonstrate an increased incidence of hemorrhoids in this population. However, rectal varices may be seen as enlarged portal-systemic collateral veins in patients with portal hypertension.304 This collateral circulation from the portal vein passes into the systemic circulation through the middle and inferior hemorrhoidal veins. In other words, hemorrhoids and rectal varices must be recognized as two separate entities. Hosking and colleagues evaluated 100 consecutive patients with cirrhosis and noted that 44% had anorectal varices.134 Goenka and associates performed a prospective study to evaluate the prevalence of this finding in 75 individuals with known portal hypertension.115 Sixty-seven (89.3%) were demonstrated to have lower gastrointestinal varices, the rectum being the most common site. There was no correlation, however, between the presence of these varices and the severity of esophagogastric mucosal changes of portal hypertension.

It is essential to differentiate anorectal varices from bleeding hemorrhoids because the treatment is so obviously different. Endoscopic ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging are noninvasive modalities for diagnosis and control after treatment.91

▶ PHYSIOLOGY

The anal sphincters of many patients with hemorrhoids demonstrate an abnormal rhythm of contraction and exert a greater force of contraction than those of asymptomatic control subjects. Whether this sphincter abnormality is a cause or an effect of hemorrhoids is not known, but it may relate to any of the hypotheses outlined. An overactive sphincter could contribute to venous congestion, expose the anal cushions to greater shearing forces, or do both by constricting the anal canal.12,125 Objective anorectal manometric studies reveal increased anal canal pressure in patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids when they are compared with control subjects.88,129,284 Sun and colleagues performed a combined manometric and ultrasonographic study of the internal anal sphincter in 20 individuals with hemorrhoids and in 20 age-matched normal controls.283 As expected, mean basal anal pressures were significantly higher in the patients with hemorrhoids than in the control patients. The mean maximal residual pressure was significantly higher in these individuals. Furthermore, direct pressure measurement in the anal canal cushions of the patients with hemorrhoids demonstrated abnormally high median pressure in comparison with that in controls. However, ultrasonographic study of the anal canal revealed a clear image of the internal sphincter that could easily be measured and was essentially no different from that of controls. The authors conclude that the absence of any significant differences in internal sphincter thickness between subjects without hemorrhoids and patients with hemorrhoids suggests that the high anal pressure observed in those with hemorrhoids is of a vascular origin.283 This elevated pressure usually returns to normal levels following hemorrhoidectomy.

The hypothesis that this condition results from chronic constipation was investigated by Gibbons and colleagues, who studied bowel habits, anal pressure profiles, and anal compliance.110 Hemorrhoids were associated with significantly longer anal high-pressure zones and significantly greater maximal resting pressures at all levels of anal distension. However, constipated women had normal pressure profiles and pressures. The study affirmed that patients with hemorrhoids are not necessarily constipated, and that chronically constipated individuals do not necessarily have hemorrhoids.

Other physiologic studies have been performed on patients with enlarged, symptomatic hemorrhoids. Various abnormalities have been reported, including increased electromyographic activity, increased external sphincter fiber density, prolonged pudendal nerve terminal motor latencies, reduced anal electrosensitivity, reduced temperature sensation, and reduced rectal compliance.306

▶ CLASSIFICATION

Hemorrhoids are classified by location (i.e., external, internal, or mixed) or by degree (i.e., first, second, third, and fourth).101 External hemorrhoids arise from the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus and are covered by modified squamous epithelium. They occur below the pectinate line and may become thrombotic and ulcerate. Internal hemorrhoids occur above the pectinate line. They may prolapse, ulcerate, bleed, and/or thrombose. They may be reducible or irreducible. Internal hemorrhoids arise from the superior hemorrhoidal plexus and are covered by mucosa. Mixed hemorrhoids (i.e., external-internal) may be prolapsed, irreducible, thrombosed, or ulcerated. They arise from the inferior and superior hemorrhoidal plexus and their anastomotic connections.

A grading system has been established for hemorrhoids, but this classification applies only to the internal variety. In first-degree hemorrhoids, the veins of the anal canal are increased in number and size, and they may bleed at the time of defecation. They do not prolapse but merely project

into the lumen. Second-degree hemorrhoids present to the outside of the anal canal during defecation but return spontaneously to within the anal canal where they remain the rest of the time. Third-degree hemorrhoids protrude outside the anal canal and require manual reduction. Fourth-degree hemorrhoids are irreducible and constantly remain in the prolapsed state.

into the lumen. Second-degree hemorrhoids present to the outside of the anal canal during defecation but return spontaneously to within the anal canal where they remain the rest of the time. Third-degree hemorrhoids protrude outside the anal canal and require manual reduction. Fourth-degree hemorrhoids are irreducible and constantly remain in the prolapsed state.

External Hemorrhoids

Two types of hemorrhoids are found at the external anal ori-fice. One occurs predominantly in the form of dilatation and engorgement of the veins beneath the skin, and the other is manifested as a thrombosis of these veins. When the clot forms, the patient becomes aware of its presence. The degree of pain depends on the size of the clot and the relationship it bears to the anal sphincters. A large clot will cause pain, but even if a clot is small, it can be quite uncomfortable if it lies within the anal musculature. Small, thrombosed hemorrhoids rarely ulcerate and bleed.

When the process spreads into external and internal tissue surrounding hemorrhoidal veins, considerable external swelling develops as edematous fluid fills the subcutaneous area at the anal margin. This may result in acute external and internal hemorrhoidal venous thrombosis and prolapse.

External Tags or Skin Tabs

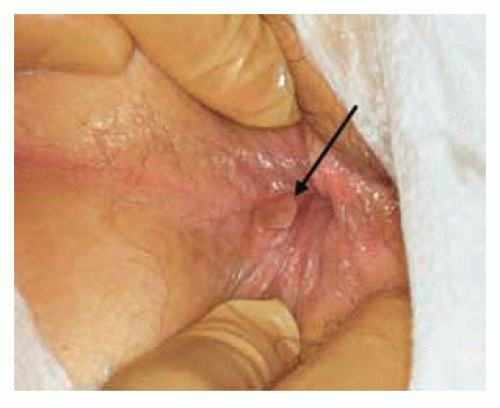

External tags or skin tabs are deformities of the skin of the external anal margin and occur as redundant folds (Figure 11-5). These may be the residual of prior thrombosed hemorrhoids that have become organized into fibrous appendages. More than likely the patient will have no antecedent history that would suggest the origin of the tags. Women, however, will often state that the tags arose during pregnancy, especially during the third trimester, persisting following delivery.18

The practice of removing hemorrhoids in three primary groups usually leaves bridges of tissue between the sites of the hemorrhoidal masses. When hemorrhoid disease is extensive, some of the diseased veins remain beneath these bridges of skin; these, too, may become fibrous skin tags after the wounds have healed (discussed later in this chapter).

Internal Hemorrhoids

The usual internal hemorrhoid is not evident on visual inspection of the anal area, especially if the patient is not bearing down. When an individual strains, a bulging mass may appear that involves all or part of the anal canal. The full extent of pressure is exerted on the anorectal outlet only during defecation or straining. Therefore, a truly reliable examination cannot be made with the patient in either the recumbent or the inverted jackknife position. Optimally, to assess the full extent of the process, examination with the patient seated on a commode is preferred.

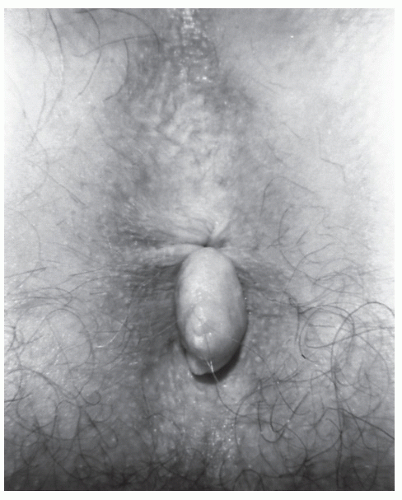

Thrombosed Hemorrhoids

Thrombosed hemorrhoids (i.e., clotted hemorrhoids) are seen most often in patients who strain while defecating or when lifting heavy objects; those who have frequent bowel actions, such as occurs with inflammatory bowel disease or malabsorption; and those who sit for long periods (e.g., long-distance truck drivers, motorcycle policemen, airline pilots, operators of heavy construction equipment). Theoretically, direct trauma to the area creates an inflammatory response, which leads to thrombosis. Additionally, the Valsalva action during straining can lead to protrusion, which, if irreducible, can precipitate this complication. Stasis of the blood flow during straining is another possible explanation.

One of the most common etiologic associations of thrombosed hemorrhoids is the maintenance of a “library” in the toilet. Virtually every patient who experiences recurrent thromboses will harbor such a home resource. Death from Fournier’s gangrene has been reported in a nonoperated patient with thrombosed hemorrhoids,30 but this must be a unique occurrence and calls into question the issue of the person being immunocompromised.

▶ DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Polyp, Adenoma, and Carcinoma

Sessile, polypoid masses (e.g., adenomas), and carcinomas, which are easily palpated or seen, should be readily differentiated from hemorrhoidal tissue. Internal hemorrhoids uncomplicated by thrombosis, edema, prolapse, or other factors are usually simple to diagnose. However, biopsy and microscopic study of any suspicious lesion are essential to establish the diagnosis with certainty. The old adage, “when in doubt, biopsy,” is worth remembering.

Hypertrophied Anal Papilla

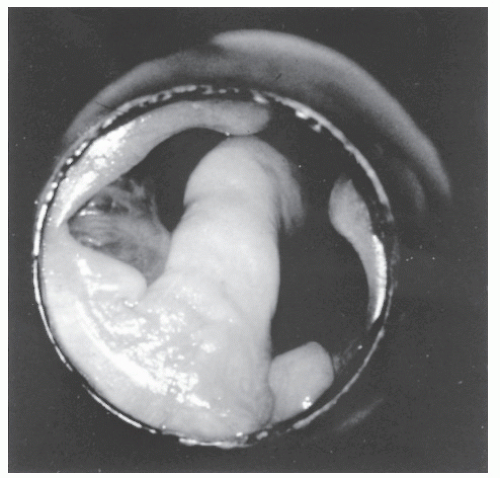

A firm mass that seems to arise from an attached pedicle in the region of the dentate line is most likely to represent a hypertrophied anal papilla (Figures 11-6 and 11-7; see Figure 12-3). Anoscopy will clarify any confusion by revealing that the pedicle arises from the dentate margin and that the entire lesion is invested by skin.

Rectal Prolapse

Rectal prolapse may be either partial, involving only the mucosal layer of the rectal wall, or complete, involving the full thickness. Partial prolapse may affect either part or all of the circumference of the anal outlet. Differentiating prolapsed internal hemorrhoids from partial or mucosal prolapse may be somewhat confusing at times, but internal hemorrhoids are separated by sulci that radiate peripherally from the center of the anal outlet, whereas mucosal prolapse usually exhibits a more uniformly concentric protrusion.

Often there is some element of mucosal prolapse when a circumferential rosette of hemorrhoids becomes irreducible and thrombosed (Figure 11-8). Complete rectal prolapse, however, should be readily distinguished by its concentrically arranged mucosal folds, which are strikingly different from the radiating sulci separating prolapsed internal hemorrhoids.

Often there is some element of mucosal prolapse when a circumferential rosette of hemorrhoids becomes irreducible and thrombosed (Figure 11-8). Complete rectal prolapse, however, should be readily distinguished by its concentrically arranged mucosal folds, which are strikingly different from the radiating sulci separating prolapsed internal hemorrhoids.

FIGURE 11-7. Prolapsed hypertrophied anal papilla. The fact that the lesion is covered by skin should eliminate confusion regarding the diagnosis. |

▶ SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The most common presenting complaint of patients with hemorrhoids is bleeding. This usually occurs during or after defecation and is exacerbated by straining and by frequent bowel actions. Blood can be evident on the paper, in the toilet bowl, or both. Occasionally, blood loss may be severe enough to produce profound anemia. Pain is usually not caused by hemorrhoids, unless the hemorrhoidal vein is thrombosed, ulcerated, or gangrenous. The most common cause of anal pain is fissure. Prolapse, either with spontaneous return or requiring manual reduction, is a common presentation of hemorrhoids. The hemorrhoids may also be irreducible. Pruritus ani is often attributed to hemorrhoids, but frequently the examination fails to reveal significant hemorrhoidal disease. That is why, unfortunately, many patients who undergo operative hemorrhoidectomy for this indication discover that the pruritic symptoms persist. Pruritus ani is a condition whose treatment includes diet, bowel management, anal hygiene, and perhaps medication (see Chapter 9).

Constipation is not a symptom of hemorrhoids, but defecation may be difficult when thrombosis or gangrene produces pain. Patients tend to avoid the toilet if hemorrhoidal symptoms are exacerbated by defecation; this can lead to refusal of the urge to pass stool and can result in constipation or even obstipation.

▶ EXAMINATION

Physical examination should include proctosigmoidoscopy and anoscopy. Colonoscopy or a barium enema study must be performed in all patients who have rectal bleeding when the source is not readily apparent from these examinations. In patients older than 50 years of age, an evaluation of the colon should be performed at some time, even if hemorrhoids are the apparent cause of the patient’s symptoms. This may be deferred if an individual’s symptoms or inconvenience preclude carrying out such studies at the time of the examination.

Kluiber and Wolff at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota reviewed in a retrospective fashion the incidence

of hemorrhoidal bleeding that produced anemia.158 The incidence of bleeding attributed to hemorrhoids that caused anemia was found to be 0.5/100,000 population per year in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1976 to 1990. The authors found that recovery from anemia after definitive treatment by means of hemorrhoidectomy was quite rapid. From a mean hemoglobin concentration before treatment of 9.4 g/dL, it was found that the hemoglobin concentration increased to 12.3 g/dL after 2 months. By 6 months, the mean hemoglobin concentration was 14.1 g/dL. The authors concluded that failure to recover hemoglobin concentration should prompt further or repeated evaluation for other causes of the anemia.158

of hemorrhoidal bleeding that produced anemia.158 The incidence of bleeding attributed to hemorrhoids that caused anemia was found to be 0.5/100,000 population per year in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1976 to 1990. The authors found that recovery from anemia after definitive treatment by means of hemorrhoidectomy was quite rapid. From a mean hemoglobin concentration before treatment of 9.4 g/dL, it was found that the hemoglobin concentration increased to 12.3 g/dL after 2 months. By 6 months, the mean hemoglobin concentration was 14.1 g/dL. The authors concluded that failure to recover hemoglobin concentration should prompt further or repeated evaluation for other causes of the anemia.158

▶ GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT

Bleeding

Bleeding, if occasional and related to straining or to diarrhea, can often be managed without specific treatment of the hemorrhoids; in other words, treatment should be directed to the cause of the bleeding. Constipation may be controlled by appropriate dietary measures, a bowel management program, stool softeners, laxatives, or a combination of these. Moesgaard and colleagues, in a prospective double-blind trial of a bulk agent (i.e., psyllium) versus a placebo in patients with bleeding and pain at defecation, noted a statistically significant difference in improvement of symptoms during a 6-week period (P < .025).192 They recommended the use of a high-fiber diet as the initial approach to the treatment of patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids. Diarrhea or frequent defecation may be managed with antidiarrheal medications and diet. Attention should also be given to improvement of anal hygiene. No less a sage than Moses Maimonides wrote in the 12th century of the importance of the nonoperative management of hemorrhoids.

MOSES MAIMONIDES (1138-1204)

|

Maimonides’ full Arabic name was Abū ‘Imrān Mūsā bin Maimūn bin ‘Ubaidallāh al-Qurt.ubī, or Mūsā ibn Maymūn in short. His full Hebrew name was Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon whose acronym forms “Rambam,” his nickname. In Latin, the Hebrew “ben” (son of) becomes the Greek-style suffix “-ides” to form “Moses Maimonides.” He was born in Cordova, Spain in 1138. His family was forced into exile in 1148, finally settling in Fez, Morocco after traveling for 10 years. Little is known of Maimonides’ formal education, but it is thought that he was essentially self-educated, evincing knowledge of Greek and Muslim writers. Hippocrates, Galen, Aristotle, Al Rhazes, and Ibn Zuhr were quoted frequently in his works. Maimonides moved again in 1165 to Fustat (now part of Old Cairo). He was later appointed court physician to the Regent of Egypt while the sultan was fighting in the crusades, and later became physician to the sultan’s son. He was also known for declining an offer from Richard the Lionhearted to be his personal physician. Maimonides was well recognized as a spiritual leader of the Jewish community in Egypt. He was one of history’s most famous rabbis. He wrote numerous books, the most famous of which was the Mishneh Torah (“Repetition of the Torah”). Compiled between 1170 and 1180, this code of Jewish religious law (Halakha) in 14 books is regarded as Maimonides’ magnum opus. He also wrote 10 medical works. His fourth such effort was a Treatise on Hemorrhoids, written for a nobleman who was thought to be a member of the sultan’s family. The paper provides an early insight into the etiology and management of hemorrhoids. Maimonides believed that surgery should be reserved for severe hemorrhoids or “closed” type (strangulated hemorrhoids). He describes the importance of changes to one’s lifestyle, diet alteration to soften stool, topical treatments, and fumigation. Maimonides died on December 12, 1204. He was buried in Tiberias, in what is now a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel. (Magrill D, Sekaran P. Maimonides: an early but accurate view on the treatment of haemorrhoids. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(979):352-354; Rosner F. The Medical Legacy of Moses Maimonides. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing House; 1998; Davidson HA. Moses Maimonides, The Man and His Works. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005; Picture. htpp://www.pneuro. com/publications/oaths/[Courtesy of Hussna Wakily, MD.])

The use of commercial topical creams, lotions, and suppositories is worthy of comment. These preparations include Tucks pads and cream, Anusol cream and suppositories, Balneol lotion, Prax, ProctoFoam, Calmol 4, micronized purified flavonoid fractions, and the most ubiquitous self-medication employed by the average American for “symptomatic hemorrhoids,” Preparation H. Preparation H has been alleged in the past to contain shark liver oil as well as a “skin respiratory factor” of unknown formulation that is supposed to improve wound healing. Its active ingredient today is phenylephrine hydrochloride (0.25%), a vasoconstrictor that may lead to temporary relief of burning and itching. Subramanyam and colleagues created rectal ulcers by performing rectal biopsy on volunteer subjects, determined the speed of healing with use of this product in suppository form, and compared it with a placebo.282 Although healing was quicker and more complete in the Preparation H group, the number of patients in the study was too small to achieve statistical significance. In my personal opinion, Preparation H acts essentially to soothe skin irritation and is as effective for this purpose as virtually any topical cream, lotion, or ointment. Symptoms of pruritus ani may be ameliorated, but there is no evidence that Preparation H causes hemorrhoids to shrink. There are also commercially available mechanical devices and products that are used to facilitate cleansing of the anus, such as mini-bidets, the Shower Mini, and the Water-pic.

Suppositories have been employed since the civilization of ancient Egypt for three basic reasons:

To promote defecation

To introduce medications into the body

To treat anorectal disease19

It is difficult to assess the actual efficacy of suppositories regarding this last condition. Because the anorectal disease is often self-limited, resolution may occur irrespective of this treatment. Furthermore, the physician cannot gainsay the psychological benefit that vigorous promotional effort of such products produces for the patient. Finally, the bulletshaped suppository often used in the treatment of anal conditions cannot exert its primary benefit within the anal canal because it must advance at least as far as the rectum. To be truly useful, Banov suggested that the suppository be hourglass or collar button shaped to maintain effective contact with the anal mucosa.22 Such a modification has yet to be produced.

If bleeding persists despite the foregoing approaches, some form of interventional treatment should be offered. If the patient believes that bleeding is caused by hemorrhoids and does not seek medical attention, or if the surgeon accepts this diagnosis without attempting to address the bleeding, a neoplasm may develop and go unrecognized. Such a situation could jeopardize the opportunity for early diagnosis and treatment.

Prolapse

Prolapsed hemorrhoids that return spontaneously or are manually reducible can usually be treated by a number of the office procedures discussed later. Attempting reduction is important because persistent prolapse predisposes the patient to thrombosis and possibly even necrosis. If the prolapse is irreducible or if an external component is present, an excisional approach may be indicated.

Pain

If pain is caused by gangrenous, ulcerated, or thrombosed hemorrhoids, a surgical procedure is the best means of treatment. If symptomatic or extensive hemorrhoids are associated with an anal fissure, hemorrhoidectomy should be considered and the fissure treated by internal anal sphincterotomy (discussed later in this chapter; see also Chapter 12). A thrombosed external hemorrhoid that produces pain is ideally managed by local excision.

The physician should consider the value of warm sitz baths in the treatment of any anal problem. Subjectively, there is little question that pain is ameliorated by the application of heat. Studies suggest there may be an explanation for how heat contributes to this response. Dodi and colleagues performed anorectal manometry on volunteers and on patients with anorectal problems (e.g., hemorrhoids, anal fissure) and determined pressure changes after immersion in warm (40° C) and cold (5° C and 23° C) water.84 In all subjects, a statistically significant decrease in resting pressure was observed after immersion in the warm water. No change was seen when patients were exposed to the colder temperatures. Because individuals with certain anal conditions often have elevated pressures, the lowering of resting anal canal pressure probably produces the observed symptomatic improvement.

▶ AMBULATORY TREATMENT

In 1993, practice parameters for ambulatory anorectal surgery were established by the Standards Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) and were subsequently revised in 2003.59,279 A disclaimer was incorporated recognizing that the guidelines were not inclusive of all proper methods and did not exclude other reasonable options. Their purpose is to provide information on which decisions can be made rather than dictate a specific form of treatment.59 Cataldo and coworkers authored another set of parameters in 2005 for the management of hemorrhoids on behalf of the ASCRS.46 Fundamentally, they concluded that the ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure falls within the purview of the treating physician. The subject of parameters and guidelines is discussed in other chapters where such management issues are addressed.

Gastroenterologists, internists, and family practitioners have all invaded the hitherto sacrosanct domain of the surgeon through the invasive treatment of hemorrhoids. This contemporary change seems reasonable when specialized training that nonsurgeons may receive in the management of other invasive techniques is considered.265 In fact, some of the tools that are advocated for the outpatient treatment of hemorrhoids are directly marketed to nonsurgeons by mail and at meetings and conventions. I believe that it is fitting and proper for any physician to perform many of the following discussed procedures, with the proviso that they are held to the same standards of care that are demanded of surgeons. Likewise, surgeons must be held to the very same criteria for competence as are gastroenterologists when they perform colonoscopy or colonoscopy-polypectomy.

Sclerotherapy: Injection Treatment of Hemorrhoids

The first attempt to obliterate hemorrhoids by means of injection was reported in 1869 by John Morgan. Morgan used iron persulfate to treat external hemorrhoids, varicose veins, and vascular lesions. In 1871, this unique form of therapy, using phenol and other chemical agents, was introduced in the United States. It was advertised as a “painless cure for piles without surgery (probably from the Latin, pila “a ball” presumably because of the shape).”10 Because specula were not available at that time, only prolapsed hemorrhoids were selected for treatment, with a single massive injection given to slough off the hemorrhoid. In 1879, Edmund Andrews, president of the Chicago Medical Society, presented a report of 3,295 patients, collected through correspondence, who had undergone injection therapy.10 Many of the patients had been treated by itinerant charlatans and inadequately trained physicians. Numerous complications, including severe pain, sloughing, and even death (nine cases), were reported. Despite these problems, Andrews believed that cautious application of the procedure was appropriate if the following criteria were met: internal hemorrhoids were treated, the patient was kept at bed rest for at least 8 hours after the procedure, and carbolic acid in oil or glycerine was employed. At about this time, Kelsey in the United States and Edwards in England recognized that the injection method was beneficial and substituted a

weaker solution of 5% to 7.5% carbolic acid in glycerine and water; this resulted in less sloughing.86,150 Phenol (5%) in almond or vegetable oil is still the primary sclerosing agent used in Great Britain today; 3 mL is usually injected into each hemorrhoid site.

weaker solution of 5% to 7.5% carbolic acid in glycerine and water; this resulted in less sloughing.86,150 Phenol (5%) in almond or vegetable oil is still the primary sclerosing agent used in Great Britain today; 3 mL is usually injected into each hemorrhoid site.

JOHN MORGAN (1820-1891)

|

Morgan was born in Bath, England, the son of a physician. After the death of his father, he moved to London and entered King’s College. As was the custom of the day, he became apprenticed to a surgeon and attended lectures, especially at St. George’s Hospital. He established himself as a surgeon in London in 1845 in the neighborhood of Hyde Park, the area being the “resort of the wealthy and successful.” Little is known about how Morgan came to employ the technique of injection, but he did achieve a significant reputation in the medical community as an anatomist and surgeon. (Morgan J. Varicose state of saphenous haemorrhoids treated successfully by the injection of tincture of persulphate of iron. Med Press Circular. 1869:29.)

EDMUND ANDREWS (1824-1904)

|

Andrews was born in Putney, Vermont. At the age of 16, he moved to Detroit and completed his literary studies at the University of Michigan, graduating in 1849. He received his medical degree 3 years later from the same university. After several years on the faculty in the department of anatomy at the university, he joined the Department of Surgery at the Rush Medical College. In 1854, Andrews founded the Chicago Academy of Sciences. During the Civil War, he served as chief of surgery at one of the camp hospitals and directed mobile surgical units in Tennessee and Mississippi, with the responsibility for maintaining the records of surgery during the war. As professor of surgery at Rush, he ultimately became dissatisfied and severed his connections there. With several other well-recognized physicians in Chicago, Andrews established the Lind University Medical School, which eventually became the Medical School of Northwestern University; for 46 years he was professor of surgery. An innovative surgeon, Andrews developed many instruments, including braces for correction of spinal curvature, an appliance for trephining, and an early endoscope that paved the way for modern cystoscopy. Following a trip to England in 1867, he was the first surgeon in the West to use and promote Lister’s antiseptic methods.

CHARLES BOYD KELSEY (1850-1917)

|

Kelsey was born in Farmington, Connecticut, the son of a Protestant minister. He received his medical degree from the College of Physicians in New York in 1873 and became a house surgeon at St. Luke’s Hospital in New York. There followed a period of 5 years in the department of anatomy at his alma mater as a demonstrator, during which time he developed a commitment to the treatment of anorectal diseases. In 1880, he was instrumental in the establishment of a hospital in New York that was “founded on the same general plan as St. Mark’s Hospital in London.” St. Paul’s Infirmary for Hemorrhoids, Fistula, and Other Diseases of the Rectum survived for only a few years, but Kelsey became recognized as one of the leading authorities on rectal surgery in the United States. His books, Surgery of the Rectum and Pelvis and Diseases of the Rectum and Anus: Their Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment, were considered the most authoritative texts in the United States at the time on the subject of rectal disease. Kelsey became professor in the Department of Diseases of the Rectum at the University of Vermont in 1889 and 2 years later occupied the same chair at the New York Postgraduate School. (Kelsey CB. Surgery of the Rectum and Pelvis. New York, NY: W. Wood; 1902; Kelsey CB. Diseases of the Rectum and Anus: Their Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: W. Wood; 1890; Banov L Jr. St. Paul’s infirmary for haemorrhoids, fistula, and other diseases of the rectum. South Med J. 1978;71(12):1559-1561.)

The combination of quinine and urea hydrochloride, widely used as a local anesthetic agent before the introduction of procaine, was associated with the development of fibrous tissue proliferation and sometimes sloughing at the site of injection.287 In 1913, Terrell first used this substance in the injection treatment of internal hemorrhoids, with dramatic results. He concluded that a 5% solution was satisfactory from the standpoint of effectiveness and the patient’s safety.287 The historical implications of the development of the injection method are well described by Anderson in his 1924 review.8 Sclerosants include sodium morrhuate and sodium tetradecyl sulfate (i.e., Sotradecol), but the safest continues to be phenol (5%) in

vegetable oil. A new sclerosing agent has been recently described and advocated from a group in Japan, that of aluminum potassium sulfate/tannic acid.291 In essence, all the ambulatory, nonexcisional treatments of hemorrhoids produce fibrosis of the submucosa, thereby obliterating the redundant tissue.

vegetable oil. A new sclerosing agent has been recently described and advocated from a group in Japan, that of aluminum potassium sulfate/tannic acid.291 In essence, all the ambulatory, nonexcisional treatments of hemorrhoids produce fibrosis of the submucosa, thereby obliterating the redundant tissue.

Indications and Contraindications

The nonprolapsing internal hemorrhoid is most amenable to injection treatment. Sometimes, a large, slightly protruding hemorrhoid can be successfully treated in this manner. Injection usually affords only temporary relief of symptoms when hemorrhoids are voluminous, contain a great deal of fibrous tissue, or require digital replacement after defecation. External hemorrhoids should never be treated by injection. Internal hemorrhoids that are infected or contain thrombi likewise should not be injected. Hemorrhoids with evidence of inflammation, such as ulceration and gangrene, are also unsuitable for injection treatment. Tags, fistulas, tumors, and anal fissures are complicating conditions that contraindicate use of the injection method.

Technique

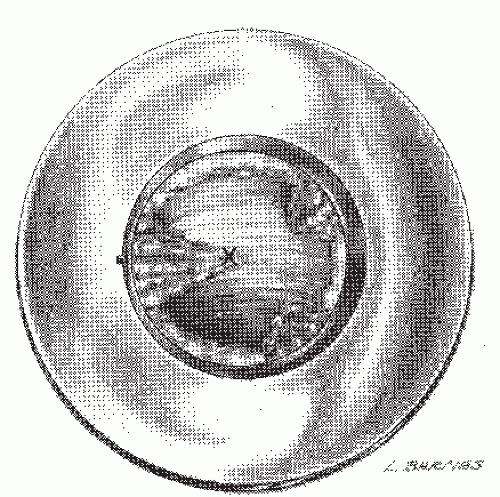

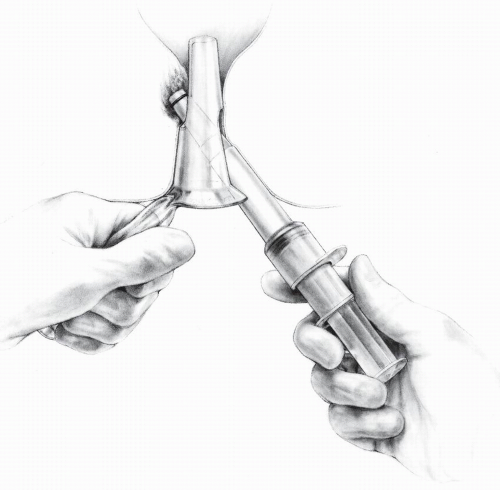

With the patient in the semi-inverted jackknife or left lateral (i.e., Sims’) position, an anoscope is inserted and the anal canal observed (Figure 11-9). The entire region is inspected so that, ideally, a diagram of the position of the hemorrhoids can be drawn on the patient’s chart (see Figure 11-1). This is especially useful when long intervals elapse between injections. The point at which each injection is made, the amount of solution used, and the date of the injection should be recorded on the chart, or at least clearly documented in the notes. The term o’clock should not be used to describe the location of the treatment or the location of the hemorrhoids. Left lateral is left lateral whether the patient is in the prone jackknife position, in the lithotomy position, or hanging from the chandelier. The use of the word o’clock mandates that the position of the patient be described, and this is inevitably absent in most office notes and communications.

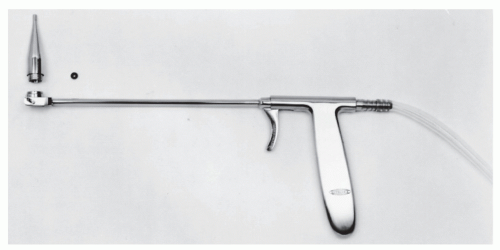

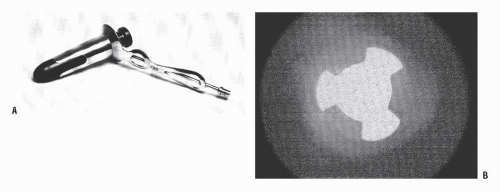

Figure 11-10 shows the syringe and long, angled needle used for sclerotherapy. Although this type of needle is very well known to head and neck surgeons, its value for the colon and rectal surgeons is not generally appreciated. More to the point, however, is the fact that standard, straight, disposable needles are a requisite for every physician’s office. Still, the longer the needle that is used (e.g., a spinal needle), the better the visualization is of the pile site.

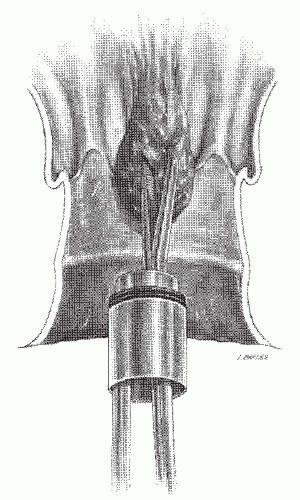

The needle is introduced through the mucous membrane into the center of the mass of veins (Figure 11-11). No antiseptic is necessary. Care must be taken to avoid bringing the point of the needle into contact with the sensitive margin of the pectinate line. Because of the extremely remote possibility that the needle could enter the lumen of a vein and that the solution could be injected into the circulation, some surgeons withdraw the plunger of the syringe to see whether blood appears. Unlike sclerotherapy for varicose veins, this technique requires that intraluminal injection be avoided, but in actuality it is virtually impossible to perform an intravenous injection.

After the needle is in position, 0.5 mL of sodium morrhuate, quinine, and urea hydrochloride, or Sotradecol is slowly injected submucosally into each pile site. Alternatively, the physician may employ a 5% solution of phenol in almond, vegetable, or arachis oil. A wheal should form, indicating that the injection was given in the proper plane. No more than 3 mL should be used in total if a commercial sclerosant is being used. Conversely, with the phenol in oil solution, 3 mL may be injected into each pile site. All hemorrhoids should be injected at the first treatment session.

A modification has been adopted by some gastroenterologists, that is, injection via a catheter passed through the channel of a colonoscope. Because gastroenterologists generally do not use anoscopy, they look at the anal canal (as best they can) through a retroflexed, long instrument. This technique is mentioned only to condemn it. However, having never attempted it, I can only imagine what a cumbersome exercise it must be to endeavor to perform sclerotherapy by this technique.

Complications

Sloughing

If sloughing follows the injection of a sclerosant, one or more of three errors are usually responsible:

The injection was too superficial.

Too much solution was injected into one area.

A second injection was made into a hemorrhoid too soon after the first.

Expectant management usually results in resolution without long-term sequelae. However, anal stricture can be a consequence of extensive tissue destruction.251

Thrombosis and Necrosis (Sloughing)

Thrombosed hemorrhoids, whether internal, external, or both, are uncommon consequences of properly performed sclerotherapy. However, necrosis of anal mucosa or perianal skin is usually the result of too superficial an injection, the injection of too much sclerosant, or the injection of overlapping areas. Generally, treatment is conservative and consists of sitz baths, analgesics, and topical anal creams. If scarring or stricture supervenes, an anoplasty should be considered (see later).

Burning

Burning in the anal canal is a late consequence of repeated sclerotherapy. The discomfort can in some patients be quite disabling, unremitting, and unresponsive to the usual local measures. Systemic pain medication may be the only effective therapy. I do not recommend repeated injections primarily because of my fear of this complication.

Local Abscess and Paraffinoma

Submucous abscess and paraffinoma (i.e., oleogranuloma) have been reported, the latter after the use of oil-based sclerosing agents (see Chapter 26).82,199

Bacteremia and Sepsis

Bacteremia following sclerotherapy has been reported in 8% of patients who undergo this procedure.2 Although septicemia did not develop in any of the patients, antibiotic prophylaxis had for a long time been recommended for those individuals at an increased risk (e.g., valvular heart disease). However, recent evidence suggests that most people with heart conditions are actually at substantially lower risk for endocarditis than previously believed, and therefore do not need endocarditis prophylaxis. Accordingly, the American Heart Association made a major revision in their guidelines on endocarditis prophylaxis in 2007, so that prophylaxis is now recommended for many fewer patients, and for fewer procedures, than previously. Endocarditis prophylaxis is now recommended only for people who are at the highest risk for endocarditis. These include

patients with artificial heart valves,

patients who have had heart repairs using prosthetic material (note: this does not include coronary artery stents),

patients with a prior history of endocarditis,

patients with certain unrepaired or incompletely repaired congenital heart disease, and

patients who have transplanted hearts who now have developed heart valve problems.

It is worth noting that the current guidelines do not recommend endocarditis prophylaxis for most patients with aortic or mitral valve disease (including those with mitral valve prolapse), or for patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The new guidelines recommend prophylaxis only for

dental procedures involving manipulation of the gums or the roots of the teeth,

procedures of the respiratory tract, and

procedures involving infected tissues.

Prophylaxis is no longer recommended for procedures of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary systems.

Other extremely rare reported complications include urologic sepsis, prostatic abscess, epididymitis, seminal vesicle abscess, urinary-perineal fistula, retroperitoneal sepsis, perineal and scrotal necrotizing fasciitis, septic shock, and rectal perforation with retroperitoneal abscess.123,245 In the era of HIV and the immunocompromised patient, one must be sensitive to the potential for an increased risk of septic complications in these individuals.

Results

Few reports of sclerotherapy have been published in contemporary English language publications. Khoury and colleagues conducted a randomized trial that compared single versus multiple phenol injections in the treatment of hemorrhoids.152 Results were assessed up to 1 year later. Most patients fell into the category of mild-to-moderate hemorrhoid disease. The authors demonstrated that a single session of injection treatment using “adequate doses of sclerosant” (i.e., 3 to 5 mL) was as effective as multiple treatments. Dencker and colleagues reported on the comparative results obtained from three forms of treatment of internal hemorrhoids—ligation, operation according to Milligan, and injection—and concluded that the results obtained with injection were poor.78 Only 21% of patients were well at the time of review. Santos and coworkers assessed the outcome following single-session sclerotherapy with 5% phenol in almond oil in 189 patients.261 With a 4-year follow-up, the authors concluded that this approach to the management of hemorrhoids provided only shortterm benefit for the majority of individuals. Additional

studies demonstrate sclerosant therapy to be less effective than a number of other options.7,105,168,272 Because other methods afforded Dencker and colleagues better results, they did not think that injection treatment should be used routinely for internal hemorrhoids.

studies demonstrate sclerosant therapy to be less effective than a number of other options.7,105,168,272 Because other methods afforded Dencker and colleagues better results, they did not think that injection treatment should be used routinely for internal hemorrhoids.

EDWARD THOMAS CAMPBELL MILLIGAN (1886-1972)

|

Milligan was born at Waterloo, near Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, the son of a gold miner. He attended Ballarat College and received his medical training at Melbourne University, graduating with honors in 1910. In 1914, he went to France with the Australian Expeditionary Force and distinguished himself by the application of the radical exploration and debridement of wounds. At the conclusion of the war, he received the Order of the British Empire and settled in London to become a consultant to a number of hospitals, including St. Mark’s. He developed an interest in anal diseases and became extremely adept in performing a combined abdominoperineal resection. It was said that he was a “master of surgical planes and deft atraumatic dissection, and even after the most major procedures his patients looked undisturbed.” One of his outstanding achievements was the work that he and his junior colleagues prepared on the detailed anatomy of the pelvis, the sphincter mechanism, and the treatment of hemorrhoids. (Milligan ETC, Morgan CN, Jones LE, et al. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal, and the operative treatment of haemorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;233:1119-1124.)

Alexander-Williams and Crapp, in a report on conservative management of hemorrhoids, stated that they had used sclerotherapy extensively in the past and as part of clinical comparative trials. They found that it gave satisfactory shortterm results, particularly in the treatment of patients with first-degree hemorrhoids.4

Opinion

I believe injection treatment is a reasonable option for the management of a limited number of individuals who have symptomatic hemorrhoids, especially bleeding, and in whom rubber band ligation cannot be tolerated (see next section). Because of my concern for the complication of intractable burning and discomfort from multiple injections, only one treatment of all pile sites is advisable. If symptoms persist, an alternative approach should be offered.

Rubber Ring Ligation

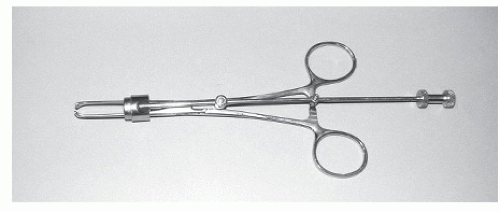

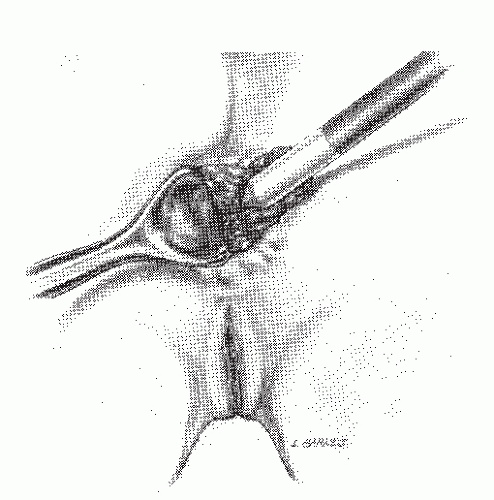

Ligation of hemorrhoids was first described by Hippocrates in 460 BC, writing about using thread to tie off the hemorrhoids. Tissue necrosis and fixation can also be produced by rubber ring ligation.80,81 In 1954, Blaisdell described an instrument for ligation of internal hemorrhoids as an outpatient procedure.36 In 1962, Barron modified this instrument and presented two series reporting excellent results (Figure 11-12).24,25 The results of the ligation technique have been so gratifying that this approach has replaced surgical hemorrhoidectomy for approximately 80% of my patients and is the primary office procedure for hemorrhoid management by surgeons in the United States.69

Any individual who has hemorrhoids manifested by bleeding, prolapse, or both is a candidate for this procedure. No anesthetic is required, but the rubber rings must be placed on an insensitive area, usually at or just above the dentate line. Skin tags or hypertrophied anal papillae cannot be treated by ligation because the patient would experience too much discomfort.

After a small cleansing enema has been given, proctosigmoidoscopy and anoscopy are performed. If the patient’s history is suggestive of colonic disease, colonoscopy or barium enema examination is completed before any treatment of the hemorrhoids is considered. Several treatments, spaced over 3- to 4-week intervals, may be required, depending on how many pile sites must be eliminated to alleviate the symptoms. Generally, I do not recommend multiple bandings in the first treatment session. I make exceptions to this policy based on patient insistence or convenience, lack of discomfort with a prior treatment, or the necessity of the patient to travel a considerable distance for subsequent therapy. However, multiple bandings are offered or routinely employed by some physicians.

Technique

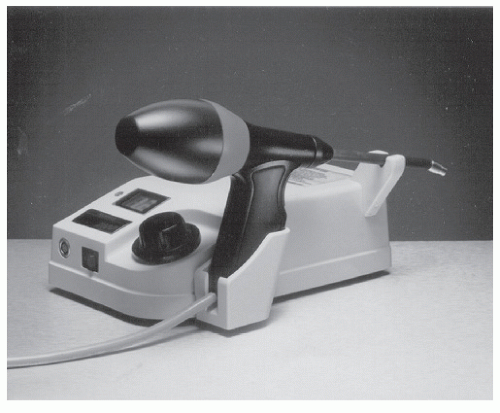

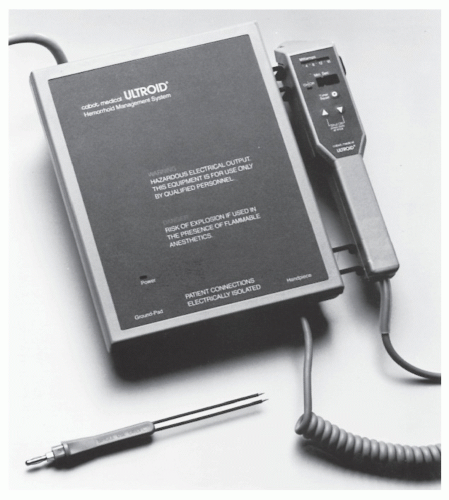

Figure 11-13 shows the McGivney ligator; I prefer this instrument to the Barron ligator. It has a much more secure shaft, which may be rotated in a 360-degree arc to facilitate placement. All nonsuction instruments have the relative disadvantage of requiring two people to perform the procedure: one to maintain the anoscope or retractor in position and the other to hold the ligator and grasping forceps. Alternatively, the physician may use a suction hemorrhoidal ligator such as the Lurz-Goltner (Figure 11-14) or the McGown ligator (Figure 11-15). These instruments draw the hemorrhoid into the cup through suction and therefore do not require a grasping forceps. Because the Lurz-Goltner ligator is a side-application device, maneuvering the ligator onto the pile is quite easy. An end-suction instrument, such as the McGown ligator, is also very simple to use, but it requires slightly more manipulation to fit onto the hemorrhoid. Conversely, the disadvantage of the side-suction ligator is that mechanical problems occasionally prevent the instrument from working optimally. Treatment with a suction ligator seems to be associated with less patient discomfort, but this is perhaps

because the drum incorporates a smaller volume of tissue. This factor, of course, is a potential disadvantage because the open-barrel device can permit incorporation of very large hemorrhoids and even redundant rectal mucosa.

because the drum incorporates a smaller volume of tissue. This factor, of course, is a potential disadvantage because the open-barrel device can permit incorporation of very large hemorrhoids and even redundant rectal mucosa.

FIGURE 11-14. Lurz-Goltner suction hemorrhoidal ligator. (Courtesy of Scanlan International, St. Paul, MN.) |

FIGURE 11-15. McGown one-hand hemorrhoidal ligator. This instrument has two interchangeable heads and a thumb suction activator. (Courtesy of George P. McGown, MD.) |

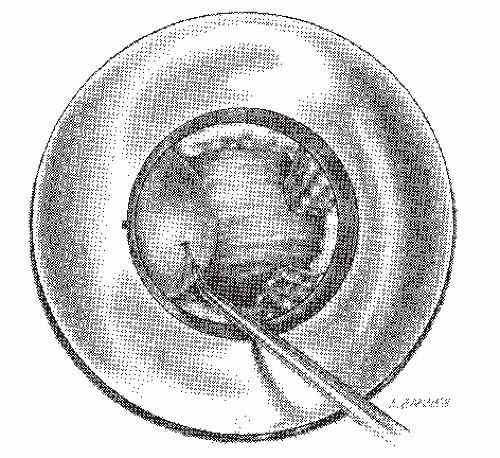

Figure 11-16 shows an anal canal in which the ligator and alligator forceps have been inserted. I personally prefer to use the long alligator forceps because they securely grab the tissue, but more importantly they facilitate clear visualization of the site to be treated. However, most surgeons are familiar with and use Allis forceps. This short instrument is less than ideal because one’s hand is often in the way, but the angled Allis forceps help somewhat in ameliorating this difficulty.

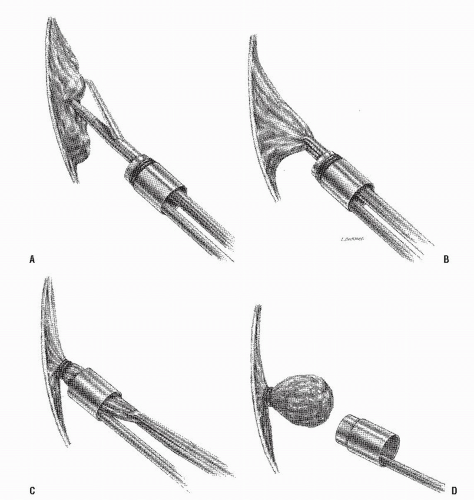

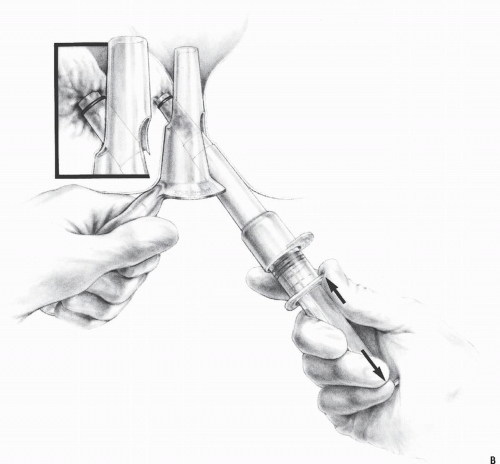

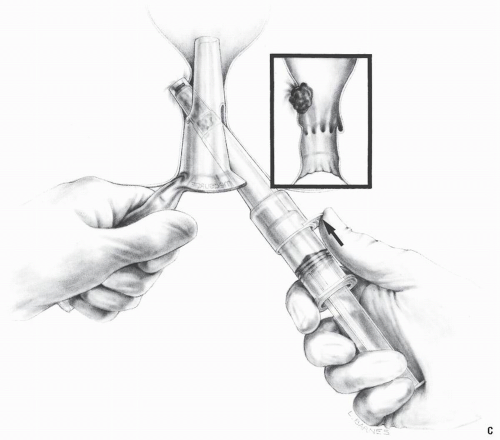

The most prominent hemorrhoid is treated first. It is grasped with the forceps as illustrated in Figure 11-17A and pulled up through the drum of the ligator (Figure 11-17B). If the patient experiences pain, a slightly more proximal point is selected, and this step is repeated. If the patient is still very uncomfortable, the wise course is to abandon this method of treatment and consider one of the alternatives. The tissue is drawn into the drum until it is taut, and the trigger is released, expelling two rubber rings (Figure 11-17C). Two rings are advised in case one breaks; there is considerable variation in the form and force of the rubber rings available on the market.147 When the rings are in place, the anoscope is withdrawn (Figure 11-17D). As previously mentioned, if the physician uses the suction ligator, no grasping instrument is required.

FIGURE 11-16. Rubber ring ligation. Alligator forceps are used to grasp the hemorrhoid. The forceps pass through the drum of the ligator. |

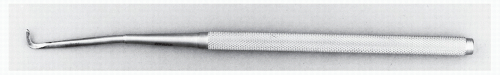

The patient rarely experiences pain so severe that removal of the rings is necessary, but if required, this can be done by interposing the end of a conventional disposable suture-removal scissors or the application of a crochet hook. George McGown (Pembroke Pines, FL) has designed a cutting hook for this sole purpose (Figure 11-18). Other methods for removing the rings, such as cutting with a scalpel, tend to precipitate bleeding. Removal of the rubber rings can be accomplished with minimal trauma within a few minutes after application. However, if the patient returns at a later time because of pain, the associated edema precludes the possibility of safe removal. Adequate analgesic medication, therefore, is the preferred option. This presupposes that sepsis is not the cause (see Complications).

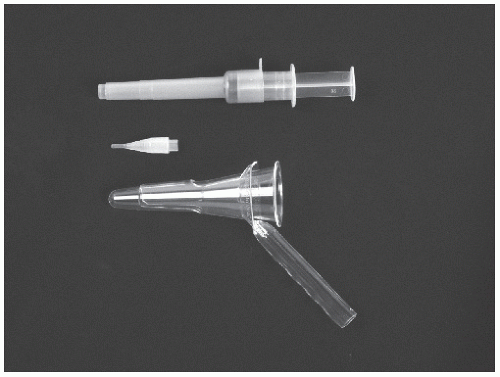

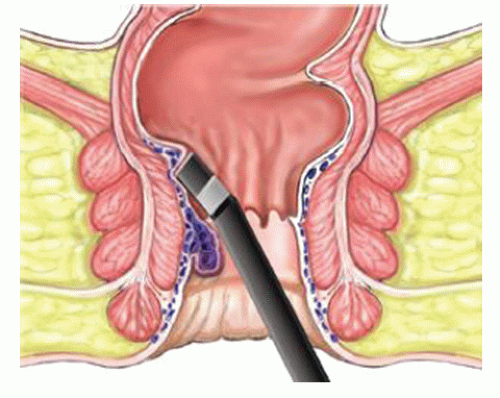

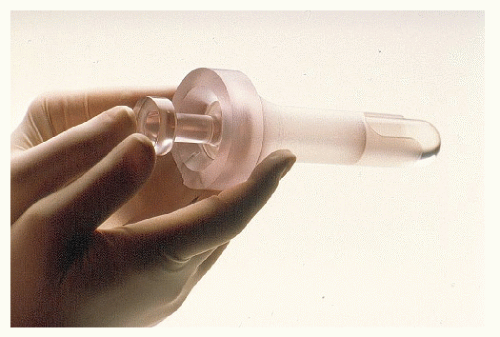

A more recent modification of a rubber band ligator has been developed, that of a disposable instrument, the O’Regan System (Figures 11-19 and 11-20). This device is a self- contained syringe-like instrument that eliminates the need for wall suction and tubing. As with the reusable instrument, it requires only one person, but clearly the primary advantage is that of disposability. In an era of concern for reprocessing costs, occupational health issues, and the risks of cross-contamination, this alternative has real merit. The technique is illustrated in Figure 11-21.

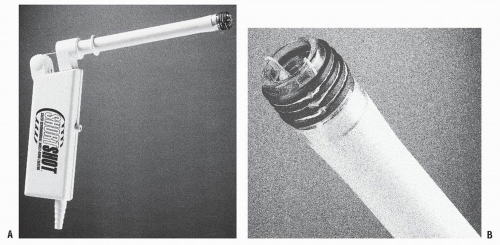

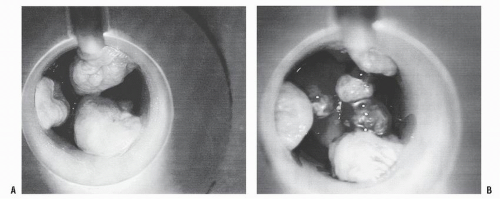

Armstrong has developed a modified anoscope with lateral apertures at the left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior quadrants in order to enable synchronous exposure and concomitant multiple hemorrhoidal ligations (Figures 11-22 and 11-23).14 Another innovation that facilitates the performance of multiple ligations in one sitting is a multiple-banding instrument, the ShortShot Saeed Hemorrhoidal Multi-Band Ligator (Figure 11-24—Cook Medical, Bloom-ington, IN). This is a fully disposable suction ligating device that permits up to four bandings with the one instrument. A similar product called Haemoband is also available preloaded with four rubber bands and a multiaction handle that fires and reloads the bands (Haemoband Surgical, Belfast, Northern Ireland). And speaking of loading the bands, this may be an exercise in frustration as the rings fly across the room when one uses the conventional applicator to set the ring onto the barrel. A simple attachment, the “magic loading cone,” (George Percy McGown, Brooklyn, NY) has been developed to address this concern (Figure 11-25).

Care Following Treatment

Bowel actions should be maintained without the patient straining. Appropriate dietary instructions, bulk agents, or a stool softener should be considered. The individual should be forewarned that some bleeding may be noted initially and again when the rubber rings are dislodged.

One of the major advantages of rubber ring ligation is its convenience. The patient need not return at fixed intervals for further ligation. Nothing is lost if one chooses to return 3 months, 6 months, or even years later. Other areas subsequently can be treated equally well despite such delays. However, the patient should realize that if symptoms are

not completely relieved, it is probably because other hemorrhoidal areas need to be addressed, assuming of course that there is no other explanation for the bleeding. Conversely, if the individual experiences complete relief after the initial ligation, there is no need to continue therapy. Under these circumstances, the patient is advised to return if and when symptoms recur.

not completely relieved, it is probably because other hemorrhoidal areas need to be addressed, assuming of course that there is no other explanation for the bleeding. Conversely, if the individual experiences complete relief after the initial ligation, there is no need to continue therapy. Under these circumstances, the patient is advised to return if and when symptoms recur.

FIGURE 11-20. O’Regan Disposable Banding System. Rubber band applicator with rings. (Courtesy of Medsurge Medical Products Corp., North Vancouver, Canada.) |

FIGURE 11-21. (continued) (B); plunger withdrawn to second position to create maximum suction (continued) |

Complications

A moderate sense of discomfort or fullness in the rectum can be anticipated for a few days following the procedure, but complaints are usually minimal and can often be relieved by sitz baths and mild analgesics. Complications are occasionally seen after rubber ring ligation and may include the following:

Delayed hemorrhage

Severe pain

External hemorrhoidal thrombosis

Ulceration

Slippage of the ligature

Fulminant sepsis

Delayed Hemorrhage

Late hemorrhage (i.e., 1 to 2 weeks after treatment) following rubber ring ligation occurs in approximately 1% of patients. As with late hemorrhage after surgical hemorrhoidectomy (see later), this may be attributed to sepsis in the pedicle or to early cutting through of the tissue.

Significant bleeding, as determined by the presence of clots or by the passage of blood without stool, requires urgent assessment, even emergency management. Patients may be evaluated in the emergency department or, if convenient, in the surgeon’s office. Anoscopic examination is mandatory. If the patient is unstable, hypotensive, or tachycardic,

hospitalization is required. It must be remembered that individuals who have undergone rubber ring ligation can bleed massively. Transfusion may be necessary. Usually a local anesthetic, field block (see later), or general or spinal anesthetic is required. If the bleeding site is identified, suture ligation is performed. If the facilities are unsatisfactory for adequate visualization and suturing, packing the anus with gauze and with a hemostatic agent such as Surgicel, Gel-foam, or Avitene may be effective on a temporary basis. The use of a Foley catheter with a 30-mL balloon has also been suggested as a useful means for tamponading the bleeding. Often, however, no active bleeding site is appreciated at the time of assessment. Under these circumstances, the use of a hemostatic agent may be reassuring, in addition to hospital admission and observation. It is because of the risk of late hemorrhage that rubber ring ligation is absolutely con-traindicated for individuals who are taking anticoagulants. An excisional option, sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation, or one of the other alternatives may be considered, unless the anticoagulant can be discontinued.

hospitalization is required. It must be remembered that individuals who have undergone rubber ring ligation can bleed massively. Transfusion may be necessary. Usually a local anesthetic, field block (see later), or general or spinal anesthetic is required. If the bleeding site is identified, suture ligation is performed. If the facilities are unsatisfactory for adequate visualization and suturing, packing the anus with gauze and with a hemostatic agent such as Surgicel, Gel-foam, or Avitene may be effective on a temporary basis. The use of a Foley catheter with a 30-mL balloon has also been suggested as a useful means for tamponading the bleeding. Often, however, no active bleeding site is appreciated at the time of assessment. Under these circumstances, the use of a hemostatic agent may be reassuring, in addition to hospital admission and observation. It is because of the risk of late hemorrhage that rubber ring ligation is absolutely con-traindicated for individuals who are taking anticoagulants. An excisional option, sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation, or one of the other alternatives may be considered, unless the anticoagulant can be discontinued.

FIGURE 11-21. (continued) (C); the pusher is advanced to release rings. The inset shows a ligated hemorrhoid pedicle. |

FIGURE 11-22. Armstrong anoscope for synchronous hemorrhoidal ligation. (Courtesy of David N. Armstrong, MD.) A: With obturator in place. B: End view without obturator. Note the lateral apertures. |

FIGURE 11-23. Multiple hemorrhoid ligations. Appearance of internal hemorrhoids prior to synchronous ligation (A) and following ligations (B). (Courtesy of David N. Armstrong, MD.) |

Pain

Pain requiring removal of the rings and measures to alleviate discomfort have been mentioned previously. Tchirkow and colleagues recommend injection of a local anesthetic solution into the hemorrhoid bundle.286 In my experience, however, in most patients who complain of pain, this symptom develops after the anesthetic effect would have dissipated.

However, a local anesthetic at the time of treatment may be a valuable adjunct if the patient is particularly apprehensive.

However, a local anesthetic at the time of treatment may be a valuable adjunct if the patient is particularly apprehensive.

In my opinion, pain is much more likely to be a source of concern if multiple bandings are attempted. Although this statement is not supported by controlled studies, it seems reasonable to conclude that the simultaneous ligation of three or more pile sites will inevitably lead to an exponential risk of discomfort. Pain that seems to worsen a few days following treatment merits reevaluation of the patient, especially if fever supervenes or if a problem with micturition develops. Anal and perineal sepsis can lead to gangrene and result in death (see Sepsis).

In the usual scenario, however, sitz baths and an over-the-counter or nonnarcotic prescription pain medication should be sufficient to relieve discomfort associated with rubber ring ligation. If the patient returns within a few hours of banding with exquisite pain, attempt at removal of the rubber rings is generally a bloody, unhappy exercise for both patient and surgeon. It is better to offer a stronger, even a narcotic prescription, rather than to struggle trying to remove the rings. Removal, if advisable, should only be performed, in my opinion, soon after banding (see Technique). With respect to subsequent management, it seems reasonable to conclude that if the patient tolerated the initial ligation poorly, an alternative approach should be considered if additional treatment be required.

Thrombosis

With ligation of internal hemorrhoids, the risk for subsequent thrombosis of corresponding external hemorrhoids is 2% to 3%. If thrombosis occurs, sitz baths and stool softeners are recommended. Occasionally, excision of the thrombosed hemorrhoid is required (see later).

Ulceration

Anal ulceration is a normal consequence of ligation. The rubber rings cause tissue necrosis, and they generally fall off in 2 to 5 days, leaving an ulcerated area. On rare occasions, a large ulcer, sometimes associated with a fissure, may be a troublesome complication. Treatment consists of sitz baths and perhaps a topical cortisone preparation, but if the fissure persists, internal anal sphincterotomy should be considered (see Chapter 12).

Slippage

The rubber rings can slip or break at any time, but this usually happens after the initial bowel movement. Breakage may be caused by a defective rubber ring, hence, the reason I prefer to use two. A more likely explanation is that it is a consequence of tension produced by a large bulk of tissue that has been ligated. The use of a mild laxative, bulking agent, or stool softener can help prevent the passage of a hard stool and, it is hoped, avoid precipitous dislodgement of the rings. If necessary, a repeat ligation of the same pile site can be reasonably performed 3 to 4 weeks after the initial procedure.

Sepsis

Aside from the normal sloughing that occurs from necrosis of tissue, sepsis following rubber ring ligation had been unknown for more than 20 years since rubber ring ligation had been generally available. A case of tetanus was reported as a possible consequence of treatment in 1978,199 but the first reported incident of a profound infection was reported by O’Hara in 1980, that of a patient who developed fatal clostridial sepsis following rubber ring ligation.215 Since this observation, others have described the same or a similar complication.62,237,253,264,275,303 There seems to be a characteristic scenario of events. Young male patients appear to be at the greatest risk. A complaint of increasing anorectal pain, perineal pain, scrotal swelling, and difficulty urinating mandates emergency evaluation. So horrendous is this complication that I specifically inform all young male patients to be aware of the warning signs.

The origin of this potentially devastating complication is unclear, but some have suggested that many of these individuals may actually be in an immunocompromised state. For example, the initial reports of this complication originated from the San Francisco Bay area before the recognition of HIV, in a community with a large gay population. Still, Moore and Fleshner report that rubber band ligation can be safely performed in selected HIV-positive patients.194 Another possible explanation is that the physician failed to recognize a septic process as the cause of the patient’s so-called hemorrhoid complaints. Obviously, the physician should vigorously seek alternative causes of anorectal complaints, especially pain, before embarking on rubber ring ligation.272 Still, there are highly experienced colon and rectal surgeons who have had the rare patient develop this complication and for whom there has been no satisfactory explanation. For example, Eugene Salvati, a former president of the ASCRS reported in a podium presentation at the society’s annual meeting that he had performed in excess of 25,000 rubber band ligations and encountered only one individual who developed a septic complication.

Findings on physical examination may include fever, perineal edema, scrotal edema, perineal ulceration, cellulitis, or frank gangrene. Rectal examination usually demonstrates a boggy, edematous anal canal that is exquisitely tender. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis are useful, especially to identify thickening of the rectal wall, gas within the wall of the bowel or within the pelvis, a pelvic fluid collection, or any other extrarectal disorder.264

Treatment requires massive antibiotic therapy, vigorous debridement, and possibly hyperbaric oxygen treatment. A colostomy may be necessary. Survival is problematic in the advanced case; those who recovered were inevitably recognized early and treated aggressively. Suggestions for prevention have included using prebanding enemas, prophylactic antibiotics, and even meticulous sterile technique (whatever that may be).148 I believe that such measures are neither appropriate nor helpful. However, I routinely administer a small-volume Fleet enema before all anorectal procedures, primarily for aesthetic purposes (I simply do not enjoy the presence of stool in the field) and the fact that usually the patient need not be concerned about defecating for the remainder of the day.

Error in Diagnosis

A theoretical disadvantage of rubber ring ligation and all the nonexcisional methods for treating hemorrhoids is that no

pathologic specimen is obtained. Invasive epidermoid carcinoma or other tumor occasionally has been reported in an excised hemorrhoid specimen (perhaps in less than l% of cases). In the rare instance of its occurrence, such a lesion will obviously be missed. However, the physician should not condemn the procedure and limit its application because of an apparently reasonable, albeit truly unwarranted, concern. One must be mindful of the fact that the standard of care no longer requires submission of a pathologic specimen even when a surgical hemorrhoidectomy is performed. Cataldo and MacKeigan reviewed more than 20,000 hemorrhoid operations over a 20-year period.47 Only one example of an unsuspected carcinoma of the anus was diagnosed solely by microscopic analysis. The authors conclude that selective rather than routine pathologic evaluation of hemorrhoidec-tomy specimens should be the policy. I concur. As stated previously, however, if there is any doubt or concern about the presence of a lesion or the possibility of an underlying malignancy, biopsy should be performed.

pathologic specimen is obtained. Invasive epidermoid carcinoma or other tumor occasionally has been reported in an excised hemorrhoid specimen (perhaps in less than l% of cases). In the rare instance of its occurrence, such a lesion will obviously be missed. However, the physician should not condemn the procedure and limit its application because of an apparently reasonable, albeit truly unwarranted, concern. One must be mindful of the fact that the standard of care no longer requires submission of a pathologic specimen even when a surgical hemorrhoidectomy is performed. Cataldo and MacKeigan reviewed more than 20,000 hemorrhoid operations over a 20-year period.47 Only one example of an unsuspected carcinoma of the anus was diagnosed solely by microscopic analysis. The authors conclude that selective rather than routine pathologic evaluation of hemorrhoidec-tomy specimens should be the policy. I concur. As stated previously, however, if there is any doubt or concern about the presence of a lesion or the possibility of an underlying malignancy, biopsy should be performed.

EUGENE PHILIP SALVATI (1923-PRESENT)

|

Eugene Salvati was born in Purslove, West Virginia, on September 7, 1923, the son and grandson of Italian immigrants. He attended college at West Virginia University, graduating from the University of Maryland Medical School in 1947. After beginning his postgraduate training at the

Muhlenberg Hospital in New Jersey, he ultimately completed his general surgery residency in Indiana at the St. Vincent’s Hospital in Indianapolis. During the Korean War, he served with the United States Medical Corps, receiving the Bronze Star and the Combat Medical Badge. He returned to complete his fellowship in colon and rectal surgery in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and began his practice in that specialty in Plainfield, New Jersey. In 1969, he established the first residency program in the specialty in the greater New York metropolitan area. In 1982, he was appointed professor of surgery at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey—Rutgers University Medical School. During his career, Salvati championed many innovative and important contributions to the field, including local treatment of rectal cancer, the management of acute diverticulitis, the use of local anesthesia in anal surgery, and the value of hemorrhoid ligation. Salvati served as president of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the American Board of Colon and Rectal Surgery, as well as the New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey Societies. The Salvati Colon and Rectal Residency Program has trained more than 100 surgeons as of 2010, “not bad for a West Virginia country boy,” as he has been fond of saying. (With appreciation to Theodore E. Eisenstat, MD.)

Results

In 1977, Bartizal and Slosberg published a retrospective review of the records of 670 patients who underwent 3,208 rubber ring ligations for internal hemorrhoids.26 The degree of discomfort after banding and the presence and amount of rectal bleeding were assessed. All were followed for a minimum of 1 month after the completion of banding.

Complications were confined to pain and bleeding. Only 21 patients (4%) had any pain. Mild pain was defined as that which did not require treatment; moderate pain required analgesics, and severe pain caused limitation of activities. No bleeding at all was reported by 642 (96%). Bleeding to a slight degree was noted by 19 (3%) but required no specific treatment. Bleeding to a significant degree occurred in 9 patients (1%). Most were treated successfully with bed rest, but two required hospitalization. When those patients who had moderate and severe pain were combined with those who had severe bleeding, only 13 (2% of all patients treated) had complications severe enough to interfere with daily activity.

Bat and coworkers performed a prospective study involving in excess of 500 patients who underwent rubber band ligation.28 The hospitalization rate was 2.5%, with approximately half of these admissions based on delayed massive rectal bleeding. There was no incident of overwhelming sepsis. An additional 4.6% suffered minor complications, including thrombosed hemorrhoids, mild bleeding, and urinary retention.