Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy for chronic gastritis achieved world-first coverage by the Japanese national health insurance scheme in 2013, making a dramatic decrease of gastric cancer–related deaths more realistic. Combining H pylori eradication therapy with endoscopic surveillance can prevent the development of gastric cancer. Even if it develops, most patients are likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, possibly resulting in fewer gastric cancer deaths. Success with the elimination of gastric cancer in Japan could lead other countries with a high incidence to consider a similar strategy, suggesting the potential for elimination of gastric cancer around the world.

Key points

- •

Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy for chronic gastritis achieved world-first coverage by the Japanese national health insurance scheme in 2013, making a dramatic decrease of gastric cancer–related deaths more realistic.

- •

Combining H pylori eradication therapy with endoscopic surveillance can prevent the development of gastric cancer. Even if gastric cancer develops, most patients are likely to be diagnosed while it is at an early stage, possibly resulting in a large decrease of gastric cancer deaths.

- •

Success with the elimination of gastric cancer in Japan could lead other countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer (China, Korea, and Latin American countries) to consider a similar strategy, suggesting the potential for elimination of gastric cancer around the world.

Introduction

After the discovery of Helicobacter pylori in 1983, the causal relationship between this bacterium and gastritis and/or gastric cancer has been steadily elucidated. In 1994, H pylori was classified as a definite carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization. Subsequently, many clinical studies were conducted in various countries to determine whether eradication of H pylori could contribute to the prevention of gastric cancer. However, the very low incidence of gastric cancer among the subjects meant that sufficient data for statistical analysis were not obtained. In 2008, a randomized multicenter clinical study conducted in Japan revealed that eradication of H pylori reduced the incidence of secondary gastric cancer by approximately two-thirds after endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer, suggesting the usefulness of H pylori eradication for prevention of gastric cancer. However, this study also showed that H pylori eradication did not completely eliminate gastric cancer. Therefore, to eliminate gastric cancer, periodic surveillance would be required after H pylori eradication. Thus, to achieve the elimination of gastric cancer in Japan, the important issue is how to combine primary prevention through H pylori eradication with secondary prevention through surveillance. Fortunately, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) approved national health insurance coverage for eradication therapy in patients with gastritis caused by H pylori infection (chronic active gastritis) on February 21, 2013, for the first time in the world.

Introduction

After the discovery of Helicobacter pylori in 1983, the causal relationship between this bacterium and gastritis and/or gastric cancer has been steadily elucidated. In 1994, H pylori was classified as a definite carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization. Subsequently, many clinical studies were conducted in various countries to determine whether eradication of H pylori could contribute to the prevention of gastric cancer. However, the very low incidence of gastric cancer among the subjects meant that sufficient data for statistical analysis were not obtained. In 2008, a randomized multicenter clinical study conducted in Japan revealed that eradication of H pylori reduced the incidence of secondary gastric cancer by approximately two-thirds after endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer, suggesting the usefulness of H pylori eradication for prevention of gastric cancer. However, this study also showed that H pylori eradication did not completely eliminate gastric cancer. Therefore, to eliminate gastric cancer, periodic surveillance would be required after H pylori eradication. Thus, to achieve the elimination of gastric cancer in Japan, the important issue is how to combine primary prevention through H pylori eradication with secondary prevention through surveillance. Fortunately, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) approved national health insurance coverage for eradication therapy in patients with gastritis caused by H pylori infection (chronic active gastritis) on February 21, 2013, for the first time in the world.

Previous preventive measures for gastric cancer in Japan

In Japan, the prevention of cancer, including gastric cancer, has primarily focused on secondary measures for early detection of cancer, rather than on primary prevention aimed at elimination of the causes. Indirect barium contrast imaging has been used as the screening method for gastric cancer, but despite the long interest and emphasis, the screening rate was only 9.6% in 2010. Screening for gastric cancer based on barium contrast imaging also does not have a high sensitivity for detecting early cancer and is associated with considerable exposure to radiation. Furthermore, targeting all people age 40 or older for screening is a major problem, as people younger than 50 account for only approximately 3% of all patients with gastric cancer in Japan. Moreover, patients who are H pylori –negative with minimal or no atrophy of the gastric mucosa are very unlikely to develop gastric cancer, such that these patients are unlikely to benefit from annual barium contrast screening and are still exposed to the adverse effects of radiation.

The most serious disadvantage with Japan’s attempts to prevent gastric cancer was the inability to implement primary prevention, which is understandable, as the cause of gastric cancer had not been identified in the 1970s when programs of screening for this cancer were begun. However, we now know that more than 95% of gastric cancers are due to H pylori infection in Japan and Korea. As a general rule for cancers caused by infections, such as liver cell cancer and cervical carcinoma, primary prevention based on preventing the infection or early eradication before significant damage is done is preferred over screening. Primary preventive measures for gastric cancer have yet to be started in Japan, and Japan has relied on barium contrast screening for 30 years. The aging of the population has increased the population at risk and thus the number of patients dying of gastric cancer has remained unchanged at approximately 50,000 per year. The lack of a reduction in the total number of deaths despite the decline in age-standardized mortality rates provided important evidence to the Japanese government that current programs were not effective in the prevention of gastric cancer deaths.

Current status and characteristics of screening for gastric cancer in Japan

Approximately 60% of patients with gastric cancer worldwide are found in only 3 East Asian countries (Japan, China, and Korea), and the disease seems to be endemic to this area. Gastric cancer was the most common cause of cancer death in Japan until it was replaced by lung cancer in 1995. Thanks to concerted efforts by clinical and fundamental researchers, the concept of early gastric cancer was proposed in Japan in 1963. At that time, early gastric cancer was defined as a lesion with infiltration of tumor cells limited to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of lymph node metastasis.

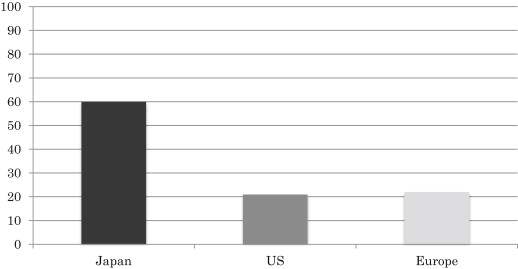

The prognosis of early gastric cancer is far better than that of advanced cancer, with a 5-year survival rate exceeding 90%. Therefore, many studies in Japan have focused on how to effectively diagnose early gastric cancer. As a result, early cancer now accounts for nearly 60% of all gastric cancers detected in Japan. This has not been reported in any other country and suggests high diagnostic capability for early cancer in the country. The efforts made so far have led to an overall 5-year survival rate of more than 60% for patients with gastric cancer in Japan. In other countries, including the United States and Europe, the 5-year survival rate of patients with gastric cancer is reported to be only 10% to 25% ( Fig. 1 ). This is not because treatment of gastric cancer is superior in Japan to that in other countries, but because the detection rate of early cancer is much lower outside Japan. In the United States and Europe, intramucosal carcinoma is not even considered to be cancer, and is classified as dysplasia. Thus, researchers in the United States and Europe have speculated that the diagnosis and treatment of precancerous lesions as early gastric cancer improves the prognosis in Japan compared with other countries. There is undoubtedly a difference of diagnostic criteria between Japan and the United States/Europe. Although Japanese pathologists make a diagnosis of gastric cancer based on the presence of atypical nuclei in gastric mucosal cells and atypical glandular or ductal structures, pathologists in the United States and Europe will diagnose gastric dysplasia instead of gastric cancer when atypical glandular and ductal structures do not extend beyond the muscularis mucosa. This difference in the diagnostic criteria for gastric cancer between Japan and the United States/Europe is an issue that seems to be difficult to resolve. However, based on the findings that 30% to 60% of lesions diagnosed as dysplasia show progression to gastric cancer within a few years, and that examination of larger biopsy specimens leads to diagnosis of more lesions as cancer, high-grade dysplasia should be classified as intramucosal gastric cancer and be treated aggressively to improve the prognosis of gastric cancer.

The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication for gastric cancer prevention

After it became clear that H pylori infection is an important risk factor for gastric cancer, the issue of whether H pylori eradication therapy can decrease the incidence of gastric cancer has attracted increasing attention. Intervention studies to assess the preventive effect of H pylori eradication on gastric cancer have been conducted in healthy individuals worldwide. However, the incidence of gastric cancer is very low in Western countries and the study populations enrolled in those countries were not large enough to detect a significant effect of eradication therapy, resulting in the discontinuation of most studies.

You and colleagues reported a study of 3365 Chinese patients who were randomized to an H pylori eradication group, a garlic group, or a vitamin group, and then were followed for 7.3 years in 2006. They found no difference of gastric cancer among the 3 groups. However, longer follow-up for 15 years subsequently revealed a significant reduction of gastric cancer in the H pylori eradication group (odds ratio 0.61; P = .032). Because the incidence of progression from H pylori –positive atrophic gastritis to gastric cancer is very low, it has been suggested that it would be difficult to demonstrate a significant difference unless the sample size is increased or the observation period is longer. Gail and colleagues recently reported that H pylori eradication at later times also has a benefit in that it stops the progression of damage and the age-related increase in cancer incidence.

We conducted a clinical trial with a small sample size and short follow-up period that involved patients who had undergone endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer, a population in which gastric cancer is very likely to develop. To investigate the ectopic recurrence of gastric cancer, 544 patients who had received endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer were randomly allocated to H pylori eradication or noneradication groups and were followed for 3 years by annual endoscopic examination. Metachronous recurrence was detected in 9 and 24 subjects from the eradication group and the noneradication group, respectively, and there was a significantly lower relapse rate in the eradication group ( P <.01 according to intention-to-treat analysis). H pylori eradication therapy reduced the incidence of differentiated gastric cancer by at least two-thirds irrespective of whether the patients had atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, or early gastric cancer. Data obtained up to 8 to 10 years after completion of this study were also analyzed, revealing a persistent difference in the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer between the H pylori eradication and noneradication groups (Kato M, Kikuchi S, Asaka M. Long-term preventive effect of H pylori eradication on the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of primary early gastric cancer. BMJ. Submitted for publication). Thus, our findings indicate that the preventive effect of H pylori eradication therapy on gastric cancer persists for a long time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree