Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Abdominoperineal Resection (HAL-APR)

Hak-Su Goh

Dean C-S Koh

Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is not just a mutilating operation. It also profoundly alters the lifestyle of a patient. It is therefore the most dreaded of all colorectal operations, and as such it is not uncommon for a surgeon to be told, “I would rather die than to have a stoma.” Fortunately, in current practice, APR is fast disappearing to become an “endangered” operation.

Diminishing requirement for APR is brought about by a combination of advances in anastomotic techniques, advent of transanal local excision, advances in chemoradiotherapy, and a better appreciation of the natural history of anorectal cancer (Table 33.1).

Table 33.1 Reasons for Diminishing Abdominoperineal Resection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For over 50 years, following the description by Miles in 1908 (1), APR was the only treatment for anorectal cancer until the introduction, followed by the slow acceptance, of anterior resection by Dixon in 1948 (2). This was a high-risk operation with significant anastomotic leak rates and mortality. Circular surgical staples popularized in the 1980s, and now accepted worldwide, allow for a safer and lower anastomosis.

A seminal advance in surgical technique is total mesorectal excision (TME) as championed by Heald (3). It dramatically improves local control of rectal cancer and allows ultra-low anterior resection to be performed. APR can be further avoided by using intersphincteric dissection with coloanal anastomosis (4,5). Functional results are not necessarily compromised by such low anastomoses because of colonic pouches, end-to-side anastomosis, or coloplasty, as well as adopting very precise rectal dissection that preserves pelvic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves (6,7,8,9). Although transanal local excision and transanal endoscopic microscopic (TEM) excision have significant recurrence rates of 20–25%, it is an important option for the very elderly and infirmed patients who are not suitable for major surgery (10).

In 1974, Norman Nigro pioneered the use of chemoradiotherapy in place of APR for anal cancers (11). The results were just as good, with the bonus of avoiding a permanent stoma. It quickly became the treatment of choice for nonadenocarcinoma anal cancers. APR is therefore reserved for salvaging failed chemoradiotherapy.

At present, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy can achieve a response rate of up to 60% for rectal adenocarcinomas, and a complete response rate of 20% in some cases (12,13). These response rates will continue to improve with ever-improving chemotherapeutic agents. With significant shrinkage and downstaging of tumors, more sphincter-saving procedures can be performed, which otherwise would require APR. The most exciting information would be the long-term outcomes of those cancers with clinical complete response. If survival and recurrence rates are similar to those of surgical excision, the need for APR will be further reduced. With metastatic rectal cancer, the standard approach has been rectal surgery first, including an APR, before chemotherapy, followed by liver or lung resections when possible (14). The rationale is to have surgical reduction of tumor bulk as well as to prevent future complications from the primary tumor such as intestinal obstruction or bleeding. The removal of the primary tumor may also prolong survival by about 5 months (15,16). This paradigm may need to be changed.

The age-standardized relative survival ratio for metastatic colorectal cancer in the United States is 5.4% for males and 7.5% for females. In Singapore, which has similar cancer survival data as Europe, it is 3.5% and 2.8%, respectively (17). With such poor survival, surgeons must take a step back to reflect on the wisdom of rushing into a mutilating operation. There are reports suggesting that, with improved chemotherapy, the incidence of future primary tumor complications is 10% or less, much lower than what is generally assumed (18). The response rate, including complete response, to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is gradually increasing. It is therefore increasingly difficult to justify APR for metastatic rectal cancer especially if there is complete response to chemoradiotherapy.

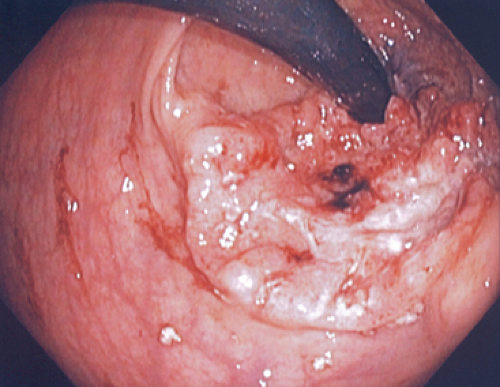

APR should be an operation of last resort when surgery is needed and sphincter salvage is not possible, such as when an adenocarcinoma has invaded the sphincter muscles or when chemoradiotherapy has failed (Fig. 33.1). Palliative APR is sometimes indicated for symptom control, but accurate preoperative assessment is critical because cutting through tumor tissues would invariably lead to local recurrence. Tumor fungating through a perineal wound is one of the most distressing problems to manage. To the purist laparoscopic colorectal surgeons, hand-assisted laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection (HAL-APR) is an oxymoron. The ultimate goal of laparoscopic surgery is to avoid having a tumor extraction abdominal scar; therefore, APR is an ideal full laparoscopic operation as the tumor is removed from the perineum. Nevertheless, the advantages of hand-assisted laparoscopic colorectal surgery over conventional open

surgery have been shown to be similar to full laparoscopic surgery (19). The remaining problem is the incisional scar from placement of the handport. Although it can be partially hidden in the skin crease of a Pfannenstiel incision, it is best to position the scar on the planned end-colostomy site to hide the scar completely.

surgery have been shown to be similar to full laparoscopic surgery (19). The remaining problem is the incisional scar from placement of the handport. Although it can be partially hidden in the skin crease of a Pfannenstiel incision, it is best to position the scar on the planned end-colostomy site to hide the scar completely.

In a case of low rectal cancer, a careful digital examination of the location, position, and fixity of the tumor is important. The critical landmark is the puborectalis muscle. It is possible to feel the distance of the tumor above the muscle as well as invasion of the muscle.

The distance between the lower margins of the tumor from the anal verge is then measured with a rigid rectoscope (sigmoidoscope) and recorded. The position of the tumor: anterior, posterior, right, or left lateral, is also determined. This orientation will influence the rectal dissection such as dissecting in front of, or behind the Denonvilliers’ fascia (20); resecting a posterior cuff of the vagina; or preserving the left or right inferior hypogastric nerves (nervi erigentes). Digital examination can also differentiate mobile tumors from fixed tumors according to fixity to the underlying muscles, especially the sphincter muscles.

For a mobile tumor, it is best to evaluate with transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), which is sensitive and accurate in assessing tumor invasion of the submucosa or the muscularis propria. For a tumor with only minimal invasion of the submucosa, the best treatment option is local excision or TEM. For a fixed tumor, the examination of choice is rectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The depth of muscle invasion and probable lymph node involvement (size >8 mm, irregular border or mixed signal intensity) are better demonstrated than TRUS or CT scan. Following TRUS examination, CT scan of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis is performed to assess for distant metastasis. If rectal MRI has been performed, CT scan of the thorax and the abdomen would suffice.

Before major rectal surgery is planned, it is absolutely essential to have a positive histological diagnosis of an adenocarcinoma. Squamous or epidermoid cancers are treated by chemoradiotherapy. Tuberculous masses or atypical inflammatory masses, which may mimic rectal cancers are not to be treated by APR. If distant metastasis is present, the patient is again best treated with chemoradiotherapy first. APR is reserved for those who have failed chemoradiotherapy or palliation of distressing symptoms. When APR is inevitable, the preoperative general preparation is similar to that of any major surgery. Patients with colorectal cancer are usually elderly with significant comorbidities. Cardiac, respiratory, or renal insufficiencies need to be corrected and optimized.

Diabetes is a major problem worldwide, not just a problem of developed countries. In Singapore, 20% of colorectal cancer patients are diabetic. They are converted to insulin on a sliding scale for their surgery with close blood glucose monitoring postoperatively until regular diet is reestablished.

Diabetes is a major problem worldwide, not just a problem of developed countries. In Singapore, 20% of colorectal cancer patients are diabetic. They are converted to insulin on a sliding scale for their surgery with close blood glucose monitoring postoperatively until regular diet is reestablished.

Specific preoperative preparation includes the following:

Height and weight of patients to calculate their body mass index (BMI). Morbidly obese patients, BMI >35 kg/m2, have significantly higher risks of wound infection and dehiscence, pulmonary embolism (PE), and renal failure (21). Perineal wound breakdown is already a major problem in patients who have received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and Ca 19.9 levels. Both may be useful in patient follow-up as persistently raised or rising cancer marker levels would indicate residual disease or recurrent disease. In addition, CEA may have a prognostic value especially in Stage II disease. In colon cancer, combination of raised CEA, lymphovascular invasion, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma is found to carry a poorer prognosis (22).

Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. For Caucasian patients, a combination of mechanical foot pumps and low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis is routine, but it remains a controversy in Asian patients. There is evidence that PE following surgery is less common among Asians, especially in Chinese patients (23,24). For these patients, full prophylactic measures are reserved only for high-risk patients (those with a history of DVT or PE, morbidly obese patients, and patients with a large tumor load). For average-risk patients, only mechanical foot pumps are used routinely.

Preoperative siting of colostomy. If a stoma therapist service is available, this is most helpful. If not, the surgeon performs the siting himself or herself. Clear instruction and stoma education go a long way to reduce patient bewilderment and anxiety.

Pain team and patient controlled anesthesia (PCA). One of the major fears of any surgical patient is pain. A pain team giving clear instruction on pain-relieving procedures such as PCA is very reassuring to patients. They can reduce not only physical pain, but also anxiety.

Physiotherapy. Physiotherapists play a very important part in the surgical team. Preoperative breathing exercises with the aid of a spirometer is important for minimizing postoperative chest atelectasis and infection especially for smokers. Education on the benefits of early postoperative mobilization and ambulation will encourage patients to ambulate early. The basic belief in many Asian communities is that staying immobilized in bed for as long as possible is best for recuperation and wound healing.

Bowel preparation. Traditionally, full mechanical bowel preparation is routine for APR. Recent evidence has shown that this is not necessary. Fleet enema to clear the rectosigmoid fecal loading is now considered sufficient.

Conventional synchronous combined APR involves two teams of surgeons operating on the abdomen and perineum simultaneously. With the laparoscopic approach, this procedure is performed sequentially. For laparoscopic dissection, the thighs have to be positioned horizontally at the hip joints for optimal laparoscopic light, instrument, and hand access to the pelvis, while the perineal dissection requires the thighs to be fully flexed to adequately “present” the perineum; for laparoscopic surgery, the abdomen needs to be distended with carbon dioxide (CO2) and this would be lost once the pelvis is entered from the perineum.

Positioning

Under standard general anesthesia, epidural analgesia is optional, the patient is positioned on the operating table as in a standard laparoscopic anterior resection (Fig. 33.2).

There are two pertinent requirements, the legs need to be in adjustable stirrups like Allen or Yellowfin stirrups for easy flexing of the thighs, and the perineum needs to be lifted off the table by placing the sacrum on a sand bag, or placing the patient on a bean bag.

There are two pertinent requirements, the legs need to be in adjustable stirrups like Allen or Yellowfin stirrups for easy flexing of the thighs, and the perineum needs to be lifted off the table by placing the sacrum on a sand bag, or placing the patient on a bean bag.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree