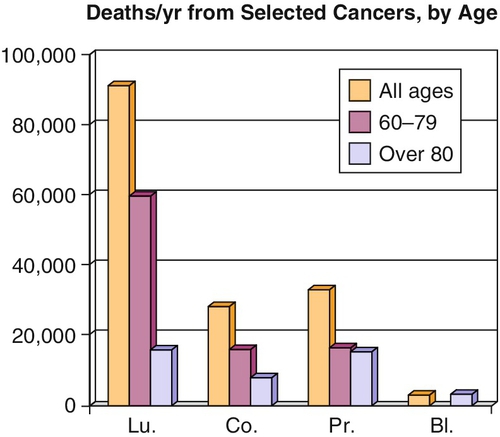

Chapter 31 George W. Drach, MD, FACS, FCPP Our growing geriatric population will impact urology in major ways over the next 2 to 3 decades. General urologists will see in their offices nearly 50% of their patients in the over-65 age group (Table 31-1). Urologists will also face difficult management decisions opting for or against major surgery in these patients. This is especially true for patients with bladder and prostatic cancer because they often do not reach the stage of invasive cancer until over age 60 (Figure 31-1). Some of these surgical candidates remain relatively healthy. Others demonstrate poor surgical risk because of their general condition and comorbidities. Table 31-1 Outpatient Visits by Medicare Patients (2006) (Adapted from Drach GW, Forciea MA: Geriatric patient care: basics for urologists, AUA Update Series 24:286–296, 2005.) Should we in urology approach these elderly patients differently from our younger, healthier patients? Yes, but the response to this question comes in modification of three elements of our usual “evaluation and management” algorithm: Steps in initial evaluation of the elderly patient differ, decision processes regarding further evaluation and recommendation for treatment require alteration, and decisions on management of definitive therapy require additional thought integrated into the milieu of aging. Several excellent sources of help exist for geriatric urology. Throughout this chapter I will refer to a small text, Geriatrics at Your Fingertips (GAYF), which is of great assistance in management of all geriatric patients. Another source is the text, Geriatrics Syllabus for Specialists. Both are available from the American Geriatrics Society, and both should be on the office bookshelf of every urologist who treats adults. In addition, the text Primer of Geriatric Urology has recently been published. To summarize, for our geriatric urology patients, one must alter the initial evaluation to include careful drug history, obtain necessary old records, and evaluate functional abilities. Therapeutic decisions must be based upon presence or absence of comorbidities along with total functional capacity, rather than chronological age. Finally, the perioperative period must include concern for optimization of comorbidities, attention to pain control, fall prevention, and early discharge planning. All possible steps to prevent or ameliorate mental status change are necessary. With these details accomplished, care of our aged patients will be more beneficial. Of course, one begins with the usual history and physical examination, but several additional inquiries and examinations are needed. A first addition includes careful attention to the medication regimen and the patient’s adherence to it. Elderly patients often do not take medications as prescribed. They may take only half doses or take daily doses only once weekly. In other cases they may not take the medication at all, perhaps because of excessive expense or their perception of side effects. In addition, one must ask them about their intake of all over-the-counter medications and herbal or other supplements that can affect their health. The average person over age 70 takes four to five prescription medications and two to four supplemental medications. These all must be recorded so that all personnel know what is actually taken. One risk buried below this medication problem is that one must avoid the routine rewriting on admission of all medications “found in the record.” What happens if you order an alpha-blocking agent such as terazosin to a patient who has not in reality taken this prescribed medication? One risks side effects such as postural hypotension and falls. On admission, order only those necessary drugs that the patient actually takes and those needed for procedural preparation (e.g., antibiotics). Another challenge is the recovery of information specific to prior treatment. Older people tend to forget details of treatments received years ago. If the patient has received radiation, what was the total dose and area of the field(s)? If the patient had surgery, what was actually done? Did the prior surgeon take out over four feet of small bowel? Even though chasing down such information can be difficult, it is very necessary. Other significant additions to the geriatric evaluation are an assessment of the cognitive, mobility, and flexibility functions. These three elements can be combined to give an estimate of the patient’s overall functional ability. First,

Geriatric Urology

Urology and aging patients

Specialty

%

Cardiology

58.4

Ophthalmology

48.5

Urology

47.9

General internal medicine

42.7

General surgery

35.8

Neurology

28.6

Dermatology

28.1

Otolaryngology

22.5

Orthopedic surgery

25.0

Family practice

25.9

Psychiatry

9.9

Gynecology

7.1

Additional content, including Self-Assessment Questions and Suggested Readings, may be accessed at www.ExpertConsult.com.

Additional content, including Self-Assessment Questions and Suggested Readings, may be accessed at www.ExpertConsult.com.

Special aspects of approach to the geriatric patient

Initial evaluation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Geriatric Urology

Figure 31-1 Most prostate cancer deaths occur after age 60. Bladder cancer deaths do not become noticeable until after age 80. Lu, Lung; Co, colon; Pr, prostate; Bl, bladder. (Adapted from Hollenbeck BK, Miller DC, Taub D, et al: Aggressive treatment for bladder cancer is associated with improved overall survival among patients 80 years old or older, Urology 64:292–297, 2004.)