Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

George D. Demetri

Brian P. Rubin

Mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract comprise a widely diverse group of neoplasms, completely separate from carcinomas or neuroendocrine tumors. This diverse grouping of tumors includes histopathological subtypes (e.g., leiomyosarcoma, leiomyoma, neurofibroma, schwannoma, desmoid fibromatosis, benign and malignant vascular tumors, glomus tumor, and other rare subtypes of sarcoma) that also can occur outside the GI tract; importantly, though, the most common subtype of mesenchymal tumor of this organ system is the subtype known as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) that occurs exclusively within the abdomen, retroperitoneum, and pelvis (1). Even before the advent of molecular-targeted therapy for this disease, much had been written about GIST, yet, until recently, these tumors defied precise histogenetic classification. Prognostication has also always been problematic. Recent advances in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of GISTs has led to fascinating new insights into the histogenesis and molecular lesions, which are fundamental to the biology and clinical behavior of GISTs. Based on these exciting developments in the molecular biology of GISTs, new approaches to therapy have been developed to target the molecular aberrancies that are causative for GISTs, and this disease is now a proof of concept for the rational investigation of “smart drugs,” which target specific pathways that are selectively activated in cancer cells. This chapter focuses on the pathological and clinical characteristics of GISTs, with an emphasis on the recent therapeutic developments in this rapidly evolving field.

Clinical Aspects

GISTs can occur at any age, although they are more common in adults, with a peak incidence in the fifth and sixth decades of life (2,3,4,5). Although numbers vary slightly from study to study, it appears that males and females are affected equally (2,3,5). Although it is not possible to know the exact incidence of GISTs in the population, these tumors are not common. A population-based retrospective study in Sweden estimated the incidence at approximately 14.5 cases per 1 million (6). In the United States, the incidence of newly diagnosed GIST has been estimated to be at least 5,000 cases per year. GIST was clearly underdiagnosed prior to the year 2000, when newer diagnostic methods (e.g., immunohistochemical staining for the KIT protein antigen, CD117) made the characterization of GIST more accurate. This incidence figure for GIST is important considering that it is commonly reported that approximately 10,000 new cases of sarcomas overall present annually in the United States. Once GIST is included in these figures, the incidence of sarcomas is certainly greater than previously reported. It is also important to note that GIST is not reported separately in large databases such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results system of the National Cancer Institute. Also, many gastroenterologists and even pathologists are increasingly finding incidental small lesions that are true GISTs (7). Such “micro-GISTs” exhibit many of the same mutations that larger, more aggressive GISTs harbor (8), although lesions <1 cm in size clearly have only a trivial risk to behave in a malignant fashion.

GISTs occur along the entire length of the GI tract but with different frequencies at different anatomical locations (Table 50.1) (9). Importantly, GISTs from different GI sites of origin also exhibit different incidences of the underlying type of molecular mechanism: In other words, the specific activating pathway (usually through a specific activating mutation in a signaling kinase such as the KIT proto-oncogene) appears to correlate with the site of origin of the primary GIST (10). GISTs are extremely rare in the esophagus. Most mesenchymal tumors of the esophagus are leiomyomas, although increasingly small GIST lesions are detected incidentally on upper endoscopy (8,11,12,13). GISTs occur most commonly in the stomach, followed by the small intestine, and are rare in the colon and rectum. GISTs may also rarely arise in the omentum, mesentery, and peritoneum, and are known collectively as extragastrointestinal GISTs.

Most small GIST lesions are asymptomatic. When large lesions are present, or if the tumor is highly infiltrative into vascular or neural structures, initial symptoms may include abdominal fullness, pain, nausea, dyspepsia, acute abdominal crisis with perforation, or evidence of GI bleeding, such as melena, hematemesis, and anemia (14,15). Large tumors may be palpable, especially when located in the stomach. Small, incidental GISTs may be diagnosed at the time of surgery for unrelated reasons and generally pursue a more benign course (8,16).

There are no known etiologic factors that predispose to the development of GISTs besides rare germline genetic conditions. There is an increased incidence of GISTs in patients with neurofibromatosis (17), the significance of which is discussed in the Future Studies section (18). In addition, GISTs are one of the tumors associated with Carney’s triad, a sporadic tumor syndrome that usually presents in childhood and is characterized by the combination of epithelioid leiomyoblastomas (GISTs), functioning extra-adrenal paragangliomas, and pulmonary chondromatous hamartomas (19). Rare familial GIST syndromes have also been described with a high penetrance of the disease and germline activation of the kinase-encoding KIT or PDGRA proto-oncogenes (20,21,22,23,24).

Pathology and Histogenesis

Grossly, GISTs are usually well-demarcated (although unencapsulated) nodules that arise from the wall of the GI tract or,

much less commonly, from the omentum, mesentery, or peritoneal surface. They vary in size from barely discernible nodules that present as incidental findings at autopsy or surgery for unrelated reasons to enormous masses measuring ≥30 cm (7,8,25,26,27). The histopathological grading of GISTs is misleading because the majority of these tumors are bland spindle cells with a rather monotonous and overall “low-grade” appearance (Fig. 50.1); approximately one-third to one-half of GIST lesions may have an epithelioid morphology or a mixture of epithelioid and spindle cells. Given the fact that even tiny GIST lesions harbor the activating mutations that are causative for GIST, it is critical to note that any GIST has the potential for malignant behavior: It is only a matter of likelihood and risk of such malignant behavior in the clinic (8). The lesions formerly called “benign GISTs” are now referred to more accurately as very low or low-risk GIST; these tend to be small, whereas more aggressively malignant lesions are more often large (>5 cm). Ulceration of the overlying mucosa is not uncommon, and cystic degeneration and necrosis can be seen in larger lesions (27). Many malignant GISTs have already metastasized at initial presentation; they present as multiple nodules, often dispersed throughout the peritoneal cavity or with liver metastases. Lesions of the more aggressively malignant GIST subtypes may also be characterized by gross invasion of adjacent organs (27). Distant metastases to extra-abdominal soft tissues are rare but reported in GISTs. Importantly, the pattern of metastatic spread in GISTs is quite different from other soft tissue sarcomas. The risk of pulmonary metastases with GISTs is significantly lower than for other pathological subtypes of sarcomas. The biological reason(s) for these observed differences in the pattern of metastases between GIST and other mesenchymal cell malignancies remains obscure.

much less commonly, from the omentum, mesentery, or peritoneal surface. They vary in size from barely discernible nodules that present as incidental findings at autopsy or surgery for unrelated reasons to enormous masses measuring ≥30 cm (7,8,25,26,27). The histopathological grading of GISTs is misleading because the majority of these tumors are bland spindle cells with a rather monotonous and overall “low-grade” appearance (Fig. 50.1); approximately one-third to one-half of GIST lesions may have an epithelioid morphology or a mixture of epithelioid and spindle cells. Given the fact that even tiny GIST lesions harbor the activating mutations that are causative for GIST, it is critical to note that any GIST has the potential for malignant behavior: It is only a matter of likelihood and risk of such malignant behavior in the clinic (8). The lesions formerly called “benign GISTs” are now referred to more accurately as very low or low-risk GIST; these tend to be small, whereas more aggressively malignant lesions are more often large (>5 cm). Ulceration of the overlying mucosa is not uncommon, and cystic degeneration and necrosis can be seen in larger lesions (27). Many malignant GISTs have already metastasized at initial presentation; they present as multiple nodules, often dispersed throughout the peritoneal cavity or with liver metastases. Lesions of the more aggressively malignant GIST subtypes may also be characterized by gross invasion of adjacent organs (27). Distant metastases to extra-abdominal soft tissues are rare but reported in GISTs. Importantly, the pattern of metastatic spread in GISTs is quite different from other soft tissue sarcomas. The risk of pulmonary metastases with GISTs is significantly lower than for other pathological subtypes of sarcomas. The biological reason(s) for these observed differences in the pattern of metastases between GIST and other mesenchymal cell malignancies remains obscure.

Table 50.1 Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors at different locations of gastrointestinal tract | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Before the use of modern pathological techniques, the vast majority of GISTs were believed to exhibit a smooth muscle phenotype. Such nonepithelial tumors of the GI tract were classified by various names, including leiomyomas, bizarre leiomyomas, leiomyoblastomas, or leiomyosarcomas (4,15,28,29,30). The evidence cited to support the smooth muscle phenotype was that the tumors usually arose from the muscular wall of the GI tract, frequently adopted a fascicular architecture, and possessed fibrillar cytoplasm. However, GISTs had some peculiar features that suggested they might not be true smooth muscle tumors. They frequently exhibited a palisaded morphologic appearance reminiscent of neural tumors, such as schwannomas. In addition, a subset of GISTs had an epithelioid appearance with atypical nuclei, at least focally, that were difficult to reconcile with a smooth muscle phenotype. These unusual histologic features were often dismissed as representing degenerative changes.

FIGURE 50.1. Hematoxylin-and-eosin section of a typical low-grade spindle cell gastrointestinal stromal tumor. (See also color Fig. 50.1.) |

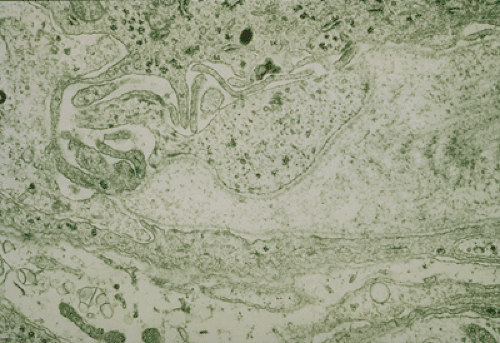

However, once the cellular microanatomy of GIST cells were studies with electron microscopy, investigators failed to find evidence to support the putative smooth muscle phenotype of GISTs (31,32,33,34,35,36,37). In contrast to leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas at other sites, actin filaments with focal densities were not abundant, and basal lamina was present only focally in most GISTs (31). In addition, GIST demonstrated ultrastructural features not usually associated with smooth muscle tumors, such as interdigitating processes. Many tumors were said to exhibit “incomplete smooth muscle differentiation” or “undifferentiated” phenotypes. In addition, subsets of GISTs were found to have unusual neuroaxonal characteristics with dense core granules (Fig. 50.2) and synapselike structures; these tumors became known as the so-called gastric autonomic neural tumors (GANTs), with other groups preferring the term plexosarcomas (32,35,36,38,39).

As immunohistochemical techniques came into widespread use and immunophenotypic data on GISTs became available, the results seemed to echo what was found with electron microscopy (2,3,35,37,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49). Results of different studies varied considerably, with anywhere from 25% to 100% of tumors showing immunoreactivity for muscle-specific actin (2,40,41,44,45,46,47,48,49), 31% to 74% displaying immunoreactivity for smooth muscle actin (3,45,47,49), and 0% to 50% binding antibodies to desmin (2,3,35,37,40,44,45,46,47,49). In addition,

some tumors revealed a neural phenotype with immunoreactivity to S-100 protein (2,3,35,37,40,41,44,45,46,47,49) and neuron-specific enolase (3,40). Still other GISTs were biphenotypic, expressing neural and partial smooth muscle phenotypes. Some GISTs failed to express any line of differentiation and were immunoreactive for vimentin only; these tumors were said to have a null phenotype (3,40).

some tumors revealed a neural phenotype with immunoreactivity to S-100 protein (2,3,35,37,40,41,44,45,46,47,49) and neuron-specific enolase (3,40). Still other GISTs were biphenotypic, expressing neural and partial smooth muscle phenotypes. Some GISTs failed to express any line of differentiation and were immunoreactive for vimentin only; these tumors were said to have a null phenotype (3,40).

FIGURE 50.2. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor with a bulbous, synapselike structure containing dense core granules. (See also color Fig. 50.2.) Source: Courtesy of Dr. Christopher Fletcher, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. |

Table 50.2 Histologic differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor | |

|---|---|

|

Due to the bewildering array of histologic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical features, the noncommittal term of GIST was popularized with the recognition that the histogenesis, although certainly mesenchymal (stromal) in nature, was unclear (35). The widespread acceptance of the term GIST for a loose collection of nonepithelial tumors of the GI tract served to simplify the classification of these bewildering stromal tumors. However, the diversity of histopathological phenotypes and lack of consistent diagnostic criteria created a situation in which many different histogenetic tumor types were grouped into an excessively broad diagnostic category of GISTs, thereby creating a clinically indistinct and biologically heterogeneous tumor category (Table 50.2). Thus, tumors once diagnosed as GIST might include not only what would today be recognized as true GISTs but also could represent less common subtypes with different underlying biological behavior, such as true smooth muscle tumors (leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma), true neural tumors (neurofibroma, schwannoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor), desmoid fibromatosis, and others. More important, unusual epithelial tumors with a mesenchymal appearance, such as sarcomatoid carcinomas, were also occasionally misclassified as GISTs. This situation has persisted until relatively recently when our understanding of GISTs has been radically altered due to the convergence of several lines of investigation (discussed in Molecular Genetics of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors section).

Behavior, Prognostic Factors, and Grading of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

There is a fascinating discordance in the experience base and the literature of pathologists, gastroenterologists, and oncologists. For many gastroenterologists, it has been widely taught that GISTs often follow a relatively indolent course. They have a tendency for local recurrence followed by metastasis only in an unusual subset of cases. This appears to be a matter of referral selection bias because many gastroenterologists care for patients with smaller lesions of lower risk. In the oncology literature, GIST is known as a consistently aggressive malignancy, with high rates of death due to recurrent and metastatic disease (50,51). Although it is difficult to obtain absolute percentages due to a lack of consistent definitions about grading and diagnosis of GISTs, approximately 50% of low-grade lesions eventually recur. Of the low-grade tumors that do recur, 60% also metastasize (usually to other intra-abdominal sites, liver, or both) (52). Virtually all high-grade GISTs recur, and >80% of those tumors that recur eventually metastasize (52). Survival seems to be site dependent. In one large study, the overall 10-year survival was 48%; however, site-specific 10-year survival was 74% for gastric tumors and 17% for small bowel tumors (2). In a separate study, the median survival was 25 months for low-grade tumors and 98 months for high-grade lesions (52).

Most GISTs are low-grade neoplasms, and yet all GISTs appear to harbor the biological ability to pursue an aggressive, metastatic course in individual patients; however, it has been difficult to determine exactly which tumors at the low-grade end of the GIST spectrum will behave aggressively (15). Of particular concern, it has been noted by several pathologists that lesions that lack any “histologic criteria for malignancy” will nonetheless occasionally metastasize (26,30). A smaller number of GISTs are obviously malignant and exhibit features that divulge their propensity for aggressive behavior (as noted later in this section). The pathology literature prior to the year 2000 is confusing with many reports of so-called “benign” GISTs. However, experts now exhibit a consensus that GISTs of histologic low grade (aside from those that are discovered incidentally and are very small [<1 cm in maximal dimension]) are virtually all low-grade malignant and should be treated and undergo clinical surveillance as such (53,54). However, very long-term follow-up (on the order of 20–30 years) is hardly ever reported in the literature and would seem to be necessary to establish that a GIST is truly benign (55). Attempts to predict prognosis have focused on various clinical and histopathological features, and these are reviewed later in this section (Table 50.3) (53,54).

Tumor location is one of the most important factors. In a mammoth study of 1,004 GISTs, tumors that arose in the stomach had a better prognosis than those that occurred in the small bowel; colon or rectum; and peritoneum, omentum, or mesentery; in fact, tumors that had origin in the colon and peritoneum, omentum, or mesentery appeared to exhibit a particularly bad prognosis (9). Esophageal tumors were reported to have the best prognosis, but in retrospect these tumors were most likely esophageal leiomyomas and not true GISTs because no attempt was made to distinguish between GISTs and smooth muscle tumors, and GISTs only rarely occur primarily in the

esophagus. These data are also supported by several smaller studies, which confirm the major conclusion that extragastric GISTs, in general, have a worse prognosis than gastric GISTs (5,42,44,56,57,58,59).

esophagus. These data are also supported by several smaller studies, which confirm the major conclusion that extragastric GISTs, in general, have a worse prognosis than gastric GISTs (5,42,44,56,57,58,59).

Table 50.3 Proposed Guidelines for Defining Risk of Aggressive Behavior in gastrointestinal stromal tumors | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Tumor stage is also an important prognostic factor, although the contributions to tumor “stage” are somewhat different in GIST compared to carcinomas of the GI tract (e.g., GISTs virtually never spread to locoregional lymph nodes, so that is not a useful component of the staging system for prognostication). In addition, invasion of adjacent organs is an adverse factor, as is the presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis, both of which are associated with a worse prognosis (14,27,56). As noted previously, the pattern of metastatic spread of GISTs is characteristic and quite different from other soft tissue sarcomas. Metastatic disease is usually confined to the liver and peritoneal cavity, and rarely to the lungs (25,26,27,29,46,52,60,61). Individual GISTs have been documented to metastasize to virtually all organs and soft tissues; however, these metastases are the exception and not the rule (25,27,52). It is unusual for GISTs to metastasize to lymph nodes, and, in the authors’ experience, lymph node metastases from purported GISTs should prompt a reappraisal of the diagnosis (26,27,29,46). The authors have frequently observed that metastatic omental or mesenteric implants that grossly resemble lymph node metastases are frequently misdiagnosed as such. Great care should be taken to identify residual lymph node tissue to determine that a tumor has indeed metastasized to a lymph node. In addition, “drop metastases” with invasion of nodal tissue may well explain incidental nodal involvement more than lymphatic spread of tumor, which does not seem to be characteristic of GISTs. The molecular mechanisms responsible for this unique pattern of spread have not been identified in GIST compared to other GI tract malignancies or other sarcomas.

The effect of age on prognosis has also been examined, and older age is associated with a worse prognosis (9,46). It has been suggested that the better prognosis associated with GISTs in the pediatric and young adult population might be attributable to their association with Carney’s triad (62). Prolonged survival has been observed in patients with Carney’s triad, even in the face of metastatic disease (63,64). The biological basis for this is unclear. However, it supports the hypothesis that the GISTs in Carney’s triad may be fundamentally distinct from sporadic GISTs in adults, which is also consistent with the fact that the GIST lesions in children tend to lack defined mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA kinase genes, and yet KIT signaling is uncontrollably active in these cells (65). Further studies, including correlations with in-depth molecular analysis of signaling pathways in this clinicopathological syndrome, are necessary to elucidate the differences between pediatric (syndromic) GIST and the sporadic GISTs of adults.

In general, GISTs are not very mitotically active compared with many other sarcomas. However, the mitotic count has been widely accepted as the best prognostic indicator (1,5,9,14,25,27,29,46,52,56,58,59,66,67,68,69). Mitotic rates in the range of >1 to 5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs) have been associated with a higher incidence of recurrences and metastases (9,26,29,46,47,56,70). Emory et al. showed that the utility of mitotic index in predicting prognosis is site dependent; although it is useful in gastric GISTs, it is not useful in stratifying those that occur in the small bowel (9). In addition, tumors without demonstrable mitotic activity have been known to recur, metastasize, or both (9,26). The presence of atypical mitoses has also been suggested as useful in predicting prognosis (56). In our own experience, atypical mitoses and significant mitotic activity (>10 mitoses per 10 HPFs) are uncommon in GISTs; their presence should prompt a reassessment of the diagnosis of GIST.

Tumor size has also been associated with aggressive behavior (16,26,29,52,53,54,56,58,59,66). Tumors <5 cm are generally indolent; however, some do behave aggressively (9,52). Small GISTs discovered incidentally at operation for other reasons are associated with a good prognosis. In one study, none of 19 tumors discovered incidentally behaved aggressively (16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree