N/A, data not available.

aIndicates differences reached statistical significance.

bThis difference was statistically significant but did not include patients who were converted to standard cholecystectomy. If included, there was no statistically significant difference in length of hospital stay.

cTotal complications.

dThis included 1 (0.7%) major biliary injury in the LC group and no major biliary injuries in the MC group.

e Histology revealed a carcinoma of the gallbladder and ultrasound at three months showed multiple liver metastases and the patient died two months later.

Further data comparing laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy are available from the meta-analysis of Shea et al. of the outcomes of 78,747 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 12,973 patients undergoing open cholecystectomy [31 ]. Mortality rates were lower for laparoscopic cholecystectomy than for open cholecystectomy, while common bile duct injury was higher for laparoscopic cholecystectomy than for open cholecystectomy. The data for common bile duct injury were re-analyzed by group-level logistic regressions to identify the differences in rates among the studies. A pattern of infrequent common duct injury in early studies, an increased incidence in studies initiated in early 1990, followed by a subsequent decrease in rate was revealed. However, the data were quite variable in terms of reporting of results and length of follow-up. The authors conceded, “there are still some considerable uncertainties that need to be addressed by better-designed studies and more complete reporting”.

Considering the current evidence, in the elective setting, laparoscopic cholecystectomy appears to be as safe as open cholecystectomy and may provide short-term improvement in quality of life. Ala, C There is a lack of convincing evidence of decreases in length of stay, recovery time or economics (hospital or societal). However, the general acceptance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy as the standard of care as well as public demand for minimally invasive surgery will prevent a future randomized controlled trial that may definitively answer these questions.

Further issues in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy

With the advent of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy, there has been a move towards ambulatory surgery. Grade A evidence from two randomized trials which compared outpatient to inpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy are available [32, 33]. Exclusion criteria included American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) III/IV, patients less than 18 and more than 70 years old, lack of a capable caregiver at home and complicated cholelithiasis (common bile duct stones or acute cholecystitis). The degree of pain, readmission and complication rates were the same in both groups. Late complications such as bile leaks became evident several days later and there was no benefit from 24-hour admission. Keulemans et al. found that 92% of the outpatients preferred outpatient care to clinical observation [33]. Of the 504 planned outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomies, Bueno Lledo et al. found that 88.8% were discharged the same day [34]. Fifty-one patients required overnight stays (10.1%), most of them for “social” causes, and five patients required 1–2 day admission for intraoperative and postoperative complications. Six patients (1.1%) required readmission. In summary, outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe and feasible option for selected patients (defined by the exclusion criteria in the randomized trials). Alc

There are two randomized trials comparing three-port versus four-port laparoscopic cholesyctectomy [35, 36]. In both studies there was no significant difference in operative time or complications. The main advantages of the three-port technique are that it causes less pain and leaves fewer scars. Again, this technique was carried out by expert hands and may not be generalized to all surgeons.

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis, inflammation secondary to obstruction of the cystic duct, is the most common complication of cholelithiasis. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the treatment of choice for acute cholecystitis and there is now little controversy concerning the use of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy. Controversy remains over the timing of cholecystectomy.

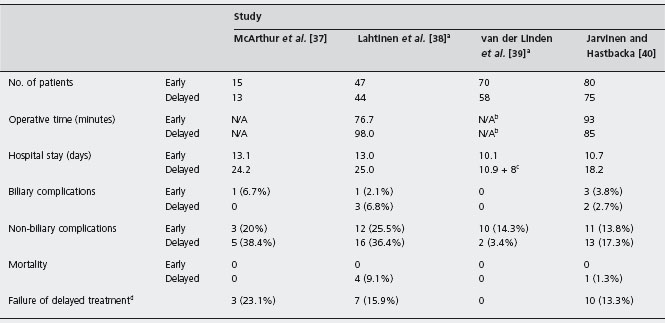

In the pre-laparoscopic era, the question of early versus delayed cholecystectomy was heavily debated. Evidence from five randomized trials carried out in the 1970s and 1980s is available [37–41]. Alc These studies demonstrated that cholecystectomy could be carried out in the acute stage with shorter hospital stay, decreased mortality and fewer operative complications (Table 23.2).

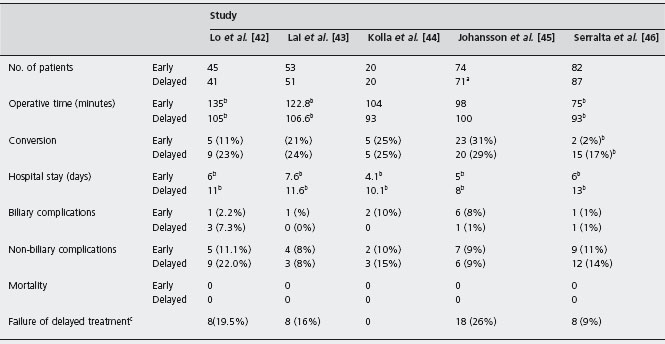

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy caused a movement to return to delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. This movement arose because laparoscopic cholecystectomy was considered to be associated with more complications and an increased risk of common bile duct injuries than interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy after the resolution of the acute episode. Grade A evidence from six randomized controlled trials on early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy is available (Table 23.3) [42–47]. Once again, the data show that early cholecystectomy, even if carried out with the laparoscopic approach, is safer and better for patients in terms of shorter illness and hospital stay, compared with delayed surgery.

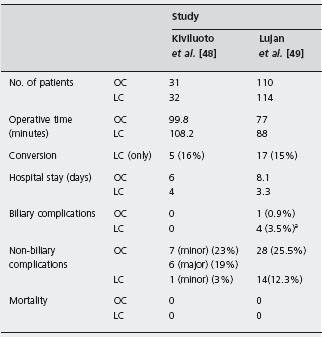

Evidence regarding laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis is available from two randomized trials [48, 49]. Alc The results are summarized in Table 23.4. The laparoscopic approach did not increase mortality or morbidity compared with the open approach and offered the benefit of shorter hospital stay. Both studies found that the rate of conversion to the open procedure was slightly higher than the average observed in elective cholecystectomy series.

Table 23.2 Randomized controlled trials comparing early versus delayed open cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis.

N/A, data not available.

aAlso showed decreased insurance payments (for time off work) for the patients treated with early cholecystectomy.

bNo average or mean time for surgery was given but the distributions of operative times were similar.

cThe mean stay for initial conservative management was 10.9 days followed by a mean stay of 8.0 days at the time of the delayed cholecystectomy.

d Patients randomized to conservative treatment initially who failed and required urgent cholecystectomy.

Table 23.3 Randomized controlled trials comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis.

aTwo patients refused surgery and were excluded.

bIndicates differences reached statistical significance.

cPatients randomized to conservat ive treatment initially who failed and required urgent cholecystectomy.

Table 23.4 Randomized controlled trials comparing open (OC) versus laparoscopic (LC) cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis.

aTwo out of four were retained common bile duct stones.

A retrospective study of 202 consecutive laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients compared complications and conversion rates when performed in the acute (<72hrs), intermediate (between 72hrs and 5 weeks) or delayed (>5 weeks) settings [50]. There was no significant difference in conversion rates (11–20%) or complication rates (7–16%) between the three groups and it was concluded that cholecystectomy can be performed safely during initial hospi-talization regardless of symptom duration. Considering the current evidence, acute cholecystitis should be treated with early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (within the first 96 hours of symptoms).

Cholecystectomy via NOTES

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) is a new technique that can be used to perform cholecys-tectomies through a transvaginal approach. The first human case was reported on 13 March 2007 by Zorron on a 43-year-old female with biliary colic [51]. Since then, Zornig reports 20 patients who have had transvaginal cholecystectomies with no intra- or postoperative complications [52]. Another three females of varying BMIs have successfully undergone cholecystectomy using the NOTES technique with no postoperative complications [53]. Also, there was a case report of a morbidly obese female with a BMI of 35.8 who had a cholecystectomy via transvaginal NOTES approach with no postoperative analgesic use and no postoperative complications [54]. Transvaginal endoscopic cholecystectomies may in the future provide a safe surgical technique for women of varying BMIs with less visible scars and less postoperative pain, but it is currently still under investigation and further research is required before its use is widely accepted.

Gallstone pancreatitis

Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Evidence from three randomized controlled trials on early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stone extraction versus conservative therapy as a treatment for biliary pancreatitis is available [55–57]. Alc In patients with severe pancreatitis or with evidence of biliary obstruction or cholangitis, early ERCP within 72 hours of presentation probably decreases morbidity and mortality rates. In patients without these criteria, early ERCP has no benefit and may in fact increase morbidity and mortality. Therefore, patients must be carefully selected for early ERCP. (See Chapter 24 for further discussion.)

Preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus cholecystectomy with cholangiogram

Gallstone pancreatitis is considered to be an indication for imaging the biliary tree with either ERCP or intraoperative cholangiogram (IOC). In order to determine if ductal evaluation is always necessary before or during cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis, Ito et al. examined 148 patients undergoing cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis [58]. Only those patients at low risk for choledocholithiasis were included (normal or decreasing liver function tests and no ductal dilation on non-invasive preoperative imaging). The choice to perform IOC was based on the preference of the operating surgeon. Twenty-seven patients underwent IOC and 121 patients did not undergo IOC. There was no difference in recurrent pancreatitis, cholangitis and asymptomatic elevation of liver function tests three months after discharge. This study suggests that direct ductal evaluation can be omitted safely in patients with low risk of choledocholithiasis.

Seven observational studies, two with controls, have assessed the optimal approach to imaging the biliary tree following an attack of gallstone pancreatitis [59–65]. Gallstone pancreatitis does not appear to be a strong predictor of CBD stones without evidence of a dilated CBD, persistently abnormal alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin, or evidence of cholangitis. Patients with these features may be considered for preoperative ERCP. C5 In one retrospective study, the incidence of procedure-induced pancreatitis was 19% in the ERCP group and 6% in the surgical/IOC group [59]. The other retrospective study demonstrated similar results with pancreatic-biliary complications in 24% of the ERCP group and 6% of the surgical/IOC group [65]. The data suggest that preoperative ERCP may in fact increase overall morbidity compared with cholecystectomy with IOC, further supporting the approach of selective ERCP in this group of patients. C5

Timing of surgery with gallstone pancreatitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree