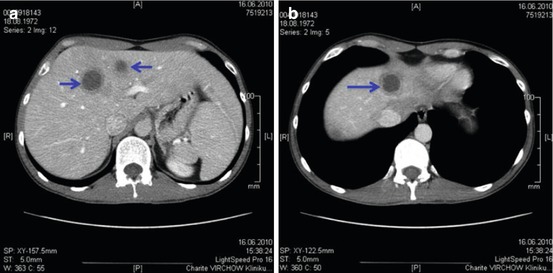

Fig. 17.1

(a–c) CT scan of three cases of liver abscesses by Klebsiella pneumoniae (Reprinted with permission from Moore et al. [5])

17.1.4 Therapy

Percutaneous drainage is required in addition to antibiotic therapy in the majority of cases, especially if the lesion is more than 3–5 cm in diameter [8, 9]. Surgical drainage is seldom required unless percutaneous approach is not feasible or a treatment for associated intra-abdominal infection is needed [7, 10].

Microbiologic tests are of capital importance for the identification of the etiologic agent and to help the choice of antibiotic: blood cultures are positive in half of the cases, and multiple sets (both aerobic and anaerobic) should be taken before the institution of empiric antibiotic therapy. In case of percutaneous or surgical drainage, samples for microbiologic examination (both Gram stain and culture) should be obtained. The importance of correct handling of the sample and its prompt dispatch to the lab, in order not to hamper the recovery of anaerobes, has to be stressed. The catheter usually is left in place for a few days until the drained volume becomes minimal.

The diagnosis of pyogenic abscess should be reevaluated if the drainage fails to give purulent material. In this case alternative differential diagnosis (amebic abscess, cyst, neoplasm) should be considered.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be guided by the suspected origin of the abscess and may be started with an association of drugs (Table 17.1).

First choice | Alternative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Metronidazole + | Ceftriaxone or Cefoxitin or Tazobactam/piperacillin or Sulbactam/ampicillin or Ciprofloxacin or Levofloxacin | Metronidazole + | Imipenem or Meropenem or Doripenem |

17.2 Amebic Liver Disease

17.2.1 Epidemiology

Amebiasis is the most aggressive intestinal human protozoan disease and is considered one of the leading causes of mortality from parasitic diseases worldwide, only surpassed by malaria, leishmaniasis, and African trypanosomiasis. The parasite is worldwide distributed; about 7–10 % of the world population is infected by one of the three human-infectious species: E. histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii with mortality rates in excess of 100,000 annually. The nonsymptomatic form is ubiquitous (prevalence: 1–5 % in temperate countries, up to 50 % in tropical areas), while the clinical pathological one is mainly seen in India and Southeast Asia or in Africa. European and American patients with amebic liver abscess classically have a history of travel to endemic areas and are typically males in the third or fourth decade of life.

17.2.2 Etiology

The principal host and source of infection is the human. Amebic infection originates from ingestion of cysts (the dehydrated survival form) of Entamoeba histolytica with contaminated food or water; interhuman transmission is rare (dirty hands, oro-genital and oro-rectal practices) [12]. In the intestinal lumen, the excystation takes place and the trophozoites perpetuate the infection. In the majority of cases, the infection (amebic infection) does not evolve in the symptomatic clinical phase (amebic illness), and the trophozoite is found in (non-diarrheic) feces in its minute form (E. histolytica minuta); this ameba does not have invasive properties. Sometimes (10 %) the infection progresses and the vegetative form of the trophozoite in its pathogenic form (E. histolytica histolytica) invades the intestinal mucosa, causing its disruption with eventual dissemination to other organs (mainly the liver through the portal system). The parasite produces proteolytic enzymes and cytotoxins able to kill leukocytes, thus halting local inflammation response and causing multiple ulcerative lesions mainly in the cecum, ascending colon, and sigmoid. This usually stimulates peristalsis, causing dysentery (amebic dysentery) sometimes with severe evolution (fulminant hemorrhagic colitis). Sometimes (1 %), not related to the severity of intestinal disease, trophozoites reach the liver sinusoids through the portal blood flow, causing microinfarcts and focal areas of hepatocyte necrosis, and in a subsequent series of lyric steps, the abscess is formed. Since the majority of the portal blood flow reaches the right hepatic lobe, usually amebic abscesses are right sided. With time a fibrous connectival wall develops (capsule) which sharply demarcates the abscess from normal liver tissue. The cavity of the abscess is filled with a thick, acellular fluid, yellowish creamy often referred as “anchovy paste” or “like chocolate.” Later calcification may develop as well as superinfection or extension to other organs: the pleura, lung, pericardium, peritoneum, spleen, and kidney (amebic extraintestinal disease).

17.2.3 Clinical Presentation

Hepatic amebiasis always needs a prior intestinal infection, but such an anamnestic element (diarrhea, gastrointestinal symptoms, abdominal pain or cramping) is present only in 15–35 % of cases. The main complaint may be irregular fever sometimes accompanied by malaise or vague digestive symptoms and right upper abdominal quadrant discomfort or even pain, possibly with posterior interscapular irradiation.

The onset of symptoms may be acute or may ensue months from a travel in an endemic area. Usually the abscess is single and right sided, but multiple lesions can also be observed.

The clinical presentation does not differ from the pyogenic liver abscess (see Sect. 17.1.3), and the differential diagnosis cannot be made on a pure clinical ground. Serology is of little help, since a positive result does not exclude other etiologies and a negative one does not rule out amebiasis [13]. Usually, however, the antibody titer is high. Stool examination is useless because cysts of Entamoeba dispar (a nonpathogen ameba) are indistinguishable from cysts of Entamoeba histolytica. US and CT scans reveal a cavity with liquid or mixed content with the lack of peripheral dense zone seen in pyogenic abscesses. Percutaneous aspiration of amebic abscess yields sterile chocolate-like or greenish material possibly without evidence of trophozoites (localized mainly in the peripheral wall). Eosinophilia usually is not present, and this can be used as a differential diagnosis criterion with hydatid disease (Fig. 17.2) (Table 17.2).

Symptoms | % |

|---|---|

Fever | 98 |

Pain | 100 |

Hepatomegaly | 80 |

Jaundice | 55 |

Vomiting | 43 |

Diarrhea | 35 |

Weight loss | 31 |

17.2.4 Therapy

Medical therapy is usually sufficient to eradicate amebic infection, and percutaneous or surgical drainage is seldom necessary. Metronidazole 750 mg thrice daily for 10 days is the first-line treatment. Tinidazole (2 g daily for 5 days) or secnidazole (500 mg TID for 5 days) may also be employed. A course of contact amebicidal agents like paromomycin (25–35 mg/kg/day p.o. divided in 3 doses × 7 days) or iodoquinol (600 mg TID p.o. × 20 days) should follow in order to sterilize the intestinal colonization by E. histolytica.

Therapeutic aspiration associated with amebicidal therapy is a well-indicated alternative in patients with large abscesses (>5 cm). Superinfected abscesses may also benefit from percutaneous aspiration. Surgery is rarely used as a treatment alternative and may be needed in case of complicated abscess or abscess rupture.

17.3 Unusual Causes of Liver Abscess

17.3.1 Listeriosis

Infections from Listeria monocytogenes usually occur in the immunocompromised host. Frequently clinical manifestations include meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or bacteremia, but liver abscesses have also been described [15]. This rare condition may mimic a neoplastic disease. The antibiotic of choice is ampicillin +/− gentamicin; co-trimoxazole may be an effective alternative.

17.3.2 Brucellosis

Brucellosis is a common zoonosis with worldwide diffusion with more than 500,000 cases per year. The Mediterranean, Middle East, Latin America, and parts of Asia constitute areas of high endemicity. The disease occurs for occupational exposure, direct or indirect contact with the infected animal (sheets, goats, cattle, pork, domestic animals) or ingestion of contaminated product, especially fresh dairy products. Bacteria are phagocytized by macrophages and monocytes and directed to the spleen, liver, bone marrow, and lymph nodes, where tissue damage and granulomas progressively develop. After the acute febrile phase, which typically occurs 2 months after infection, in untreated (or undertreated) patients, chronic infection can develop.

Hepatic brucelloma is a rare localization occurring in the chronic phase of the disease and may be difficult to diagnose if not accompanied by symptoms typical of the systemic disease. Usually abscesses are single (but multiple abscesses also have been described) and hypoechoic, right sided, 3–10 cm in size, and with a central calcification. Abscesses show one or more loculi whose walls can show a contrast enhancement on TC scan.

Therapy of chronic brucellosis is still an object of debate: usually rifampin, doxycycline, streptomycin, and co–trimoxazole are used in various combinations and for long courses [16].

17.3.3 Tuberculosis

Tubercular liver abscess is a rare disease which occurs usually in the clinical setting of a pulmonary or intestinal tuberculosis. Together with fever and weight loss, ascites is the principal symptom. CA-125 is very high in almost all cases, and this can lead to misdiagnosis. Peritoneal fluid usually has an exudative appearance, the cellular component mostly constituted by lymphocytes. Acid-fast stain is usually negative. Cultures give positive results in about a third of cases, but they take as long as 6 weeks to grow. PCR can help the diagnosis in most cases [17].

17.3.4 Actinomycosis

Hepatic actinomycosis is a rare disease and usually originates from dissemination from other abdominal sites of infection. Symptoms are often nonspecific (nausea, malaise, weight loss, and fever). Alkaline phosphatase is usually elevated. The typical appearance is that of multiple hepatic abscesses often of small dimensions. Percutaneous aspiration may allow the diagnosis by detection of “sulfur granules” with Gram-positive acid-fast bacilli or by culture (provided that specimen is correctly handled and promptly placed in anaerobic conditions). Intravenous high-dose penicillin is the treatment of choice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree