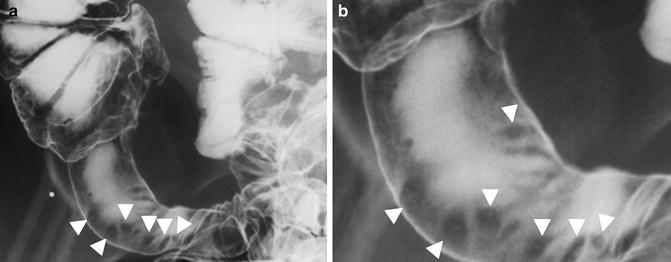

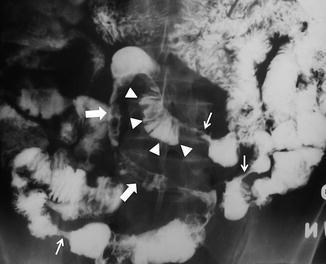

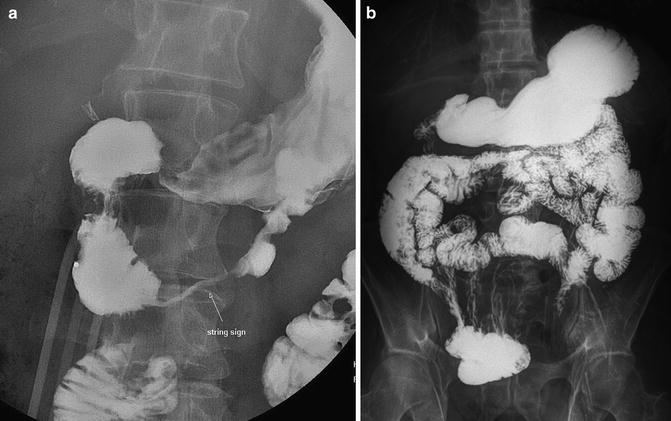

Fig. 3.1

A 17-year-old male on Adalimumab and steroids with persistent abdominal pain. Images show serial spot films from a SBFT demonstrating (a) lymphoid hyperplasia (in brackets), (a) aphthous ulcerations along the mesenteric border (arrows), (b and c) mesenteric border linear ulcer (arrowheads), and (b) a long intramural sinus tract (small arrows). (c) The mesenteric border ulcer is viewed in profile and enface. In most small bowel lesions with mucosal inflammation, multiple radiographic findings will be present

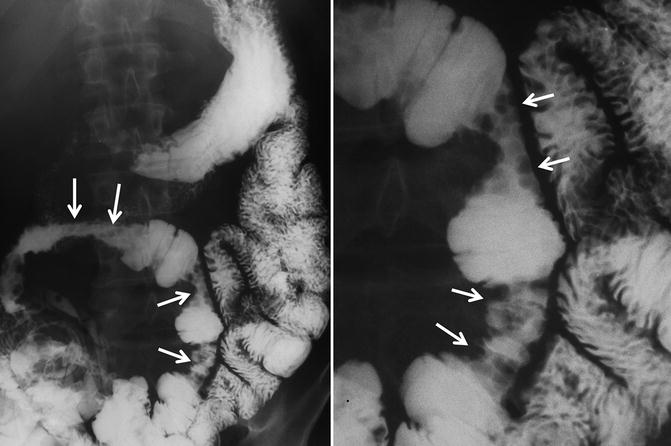

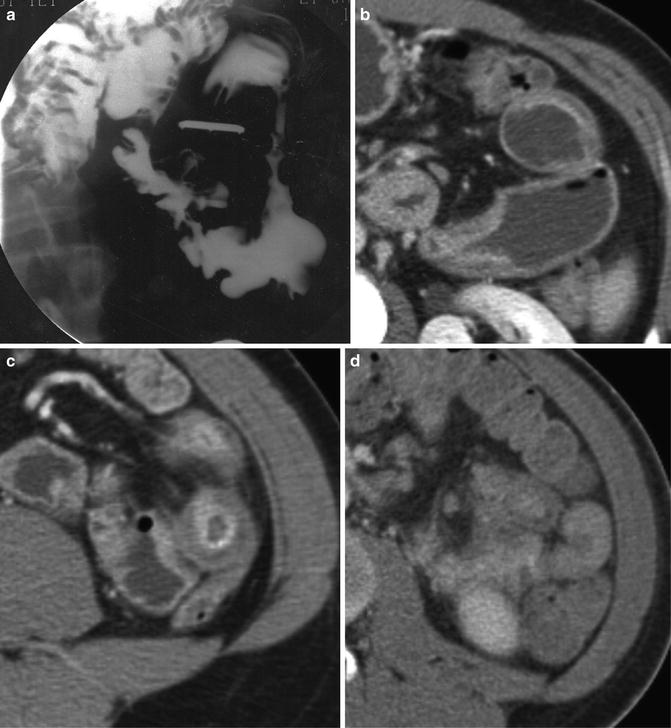

Fig. 3.2

(a, b) Peroral pneumocolon demonstrating double contrast appearance of aphthous erosions (arrowheads) in the terminal ilium

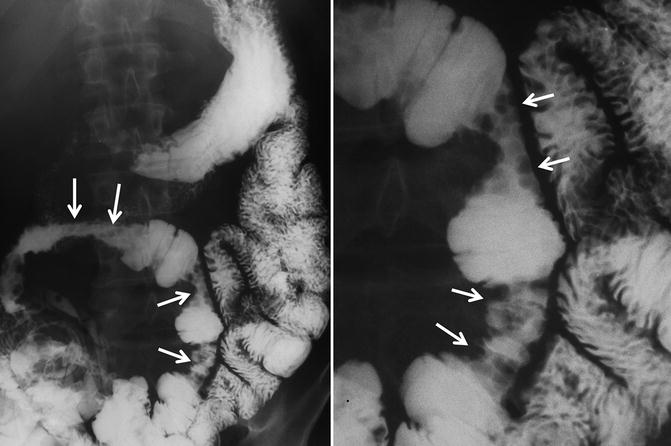

Aphthous ulcerations are best seen using double contrast technique or with careful palpation [11]. As ulcerations progress and become deeper, longitudinal and transverse ulcers coalesce and combine with edema and traction to form the classic cobblestone pattern (Fig. 3.3) [2]. Transmural ulcerations can progress to form “rose thorn” ulcers, which project perpendicularly beyond the lumen.

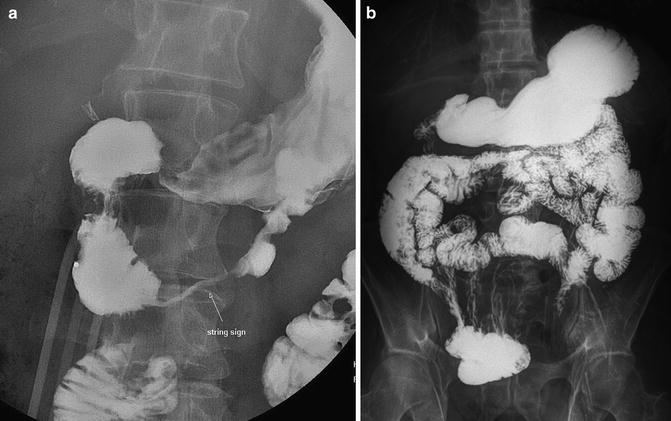

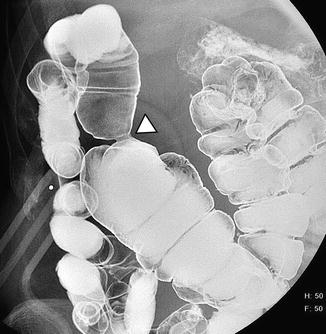

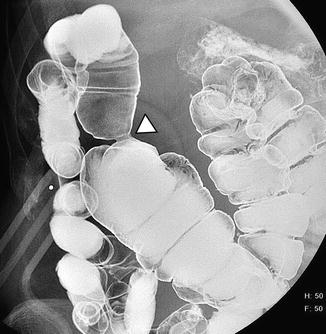

Fig. 3.3

Small bowel follow-through from 42-year-old man with multiple segments of ileum involved by Crohn’s-related inflammation, demonstrating confluent linear and transverse ulcers showing a cobblestone pattern (arrows). Cobblestone pattern arises from a combination of linear and transverse ulcers, edema, and sometimes fibrosis

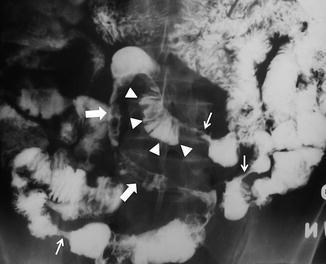

One of the early morphologic patterns recognized by Marshak, Herlinger, and others is the asymmetric inflammation of Crohn’s, which is generally most pronounced along the mesenteric border of the small bowel. Inflammation and edema along the mesenteric border leads to straightening of the mesenteric border, with ulcerations occurring in this region. Ulcerations can progress and coalesce until the classic mesenteric border linear ulcer of Crohn’s disease is seen. This is a pathognomonic finding (Figs. 3.1 and 3.3) [9]. In profile, the linear ulcer often has a shaggy appearance due to mucosal erosion with a nearby line of radiolucency representing edema surrounding the ulcer (Fig. 3.1). As the disease progresses, sacculations occur along the antimesenteric border of the bowel lumen, where there is a relative absence of inflammation and fibrosis (Fig. 3.4). Straightening of the mesenteric border can also be due to fibrofatty proliferation, which also occurs along the mesenteric side and is seen as creeping fat at surgery. At fluoroscopy, fibrofatty proliferation displaces normal bowel loops away from involved loops and crowds the uninvolved loops into different areas of the abdominopelvic cavity. In the rectum, fibrofatty proliferation displaces other bowel loops superiorly in the pelvis.

Fig. 3.4

Small bowel follow-through demonstrating the string sign (small arrows), antimesenteric border sacculation (arrowheads), and long segmental involvement with cobblestoning (large arrows)

Spasm of mildly inflamed small bowel is a known early sign of Crohn’s disease. One of the strengths of fluoroscopy is the ability to visualize luminal narrowing in real time to discriminate between true narrowing and spasm. Fluoroscopy can be used to accurately measure stricture length without resorting to post processing methods or crude estimation across multiple slices, and to map nearby strictures preoperatively for potential surgical resection or strictureplasty (Fig. 3.4). While CT and MR enterography are highly accurate for the detection of strictures and fistulae [12], clear delineation of multiple strictures is sometimes problematic as areas of spasm or collapse can be misinterpreted [13].

Small Bowel Follow Through

SBFT is performed by having the patient ingest multiple cups of thin liquid barium and fluoroscopically evaluating the contrast column from the duodenal bulb to the terminal ileum. Frequent palpation under fluoroscopy should be performed to efface the small bowel loops to visualize aphthous ulcers and other radiographic features, in addition to assessing peristalsis and fixation of small bowel loops. Occasional overhead images provide a global view of diseased loops and their location. While large volumes of barium are generally used to speed the examination and unmask strictures and obstructing lesions, smaller volumes can also be used in patients unwilling to ingest the large volumes necessary for CT and MR enterography.

Several studies of patients with known or suspected Crohn’s disease who underwent cross-sectional enterography and SBFT by experienced fluoroscopists have been performed. They demonstrate slight but significantly decreased sensitivity and unchanged specificity for SBFT compared to CT enterography for detecting active mural inflammation [14–17]. When intubation of the terminal ileum can be successfully accomplished at colonoscopy, there is little improvement in cost effectiveness when performing additional SBFT; however, incremental effectiveness is substantial when terminal ileal intubation cannot be performed [18].

SBFT has several relative strengths compared to CT and MR enterography, which should be exploited in the appropriate clinical contexts. Real-time examination permits the best and easiest distinction between spasm, collapse and stricture. During CT enterography, usually only one acquisition of the bowel is performed to minimize radiation dose. Observation over time is permitted at fluoroscopy. Additionally, inexperienced radiologists not infrequently overlook jejunal inflammation at CT enterography (manifested by asymmetric wall thickening and hyperenhancement) or confuse it with the normal feathery appearance of the valvulae conniventes or jejunal collapse, which is observed in approximately one-third of routine CT enterography cases. Advanced jejunal inflammation can be entirely occult at routine abdominopelvic CT, when bowel loops are not distended. At fluoroscopy, advanced inflammatory changes cannot be confused with the jejunal fold pattern of the valvulae conniventes, as the bowel loops are markedly distorted by cobblestoning, linear ulcers with sacculation, and stricture formation (Fig. 3.5). While fluoroscopy can take longer when smaller volumes of barium are ingested, fluoroscopists can examine the patient over multiple time-points (sometimes several hours), so patients that are unwilling to consume large volumes of enteric contrast can be imaged. As such, fluoroscopy provides the best overview for complex postoperative anatomy, stricture mapping, as well as providing the easiest method for estimating small bowel length [19] (Fig. 3.6). As such, side-to-side anastomoses are sometimes mistaken at cross-sectional enterography for dilated segments proximal to a stricture, and such postoperative changes are easily determined at fluoroscopy.

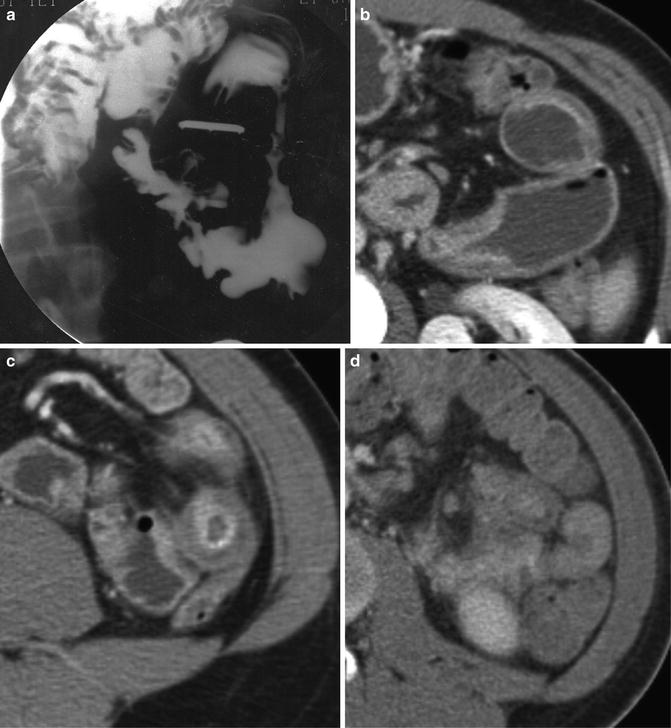

Fig. 3.5

Jejunal Crohn’s disease as demonstrated by (a) small bowel fluoroscopy, and (b and c) CT enterography. Findings such as asymmetric narrowing and string sign are easy to identify at small bowel follow-through, with recognition of analogous cross-sectional findings required at CT enterography; e.g., (b and c) asymmetric wall thickening and hyperenhancement, and target sign, but entirely occult at (d) routine abdominal CT

Fig. 3.6

Single contrast upper GI demonstrating a long segment duodenal stricture (the string sign). Small bowel follow through represents an ideal way to measure (a) the length of strictures and (b) bowel length (in a patient with prior colectomy)

Peroral pneumocolon is performed after a SBFT by insufflating air into the colon (Fig. 3.2). Air refluxes into the terminal or neo-terminal ileum to provide exquisite double contrast images of the ileal mucosa (Fig. 3.7). This double contrast technique is extremely useful as the distention allows excellent evaluation of anastomotic and ileal strictures (Fig. 3.8).

Fig. 3.7

Images from a peroral pneumocolon clearly show aphthous erosions (arrows) in a distended terminal ileum, in addition to a widely patent ileocolic anastomosis (arrowheads)

Fig. 3.8

Peroral pneumocolon in another patient with prior right hemicolectomy and end-to-end ileotransverse colostomy demonstrates a stricture at the ileocolic anastomosis (arrowhead), but normal mucosa in the terminal ileum

There are no prospective studies that we are aware of comparing cross-sectional imaging techniques to the SBFT with peroral pneumocolon for the detection of active inflammation. The strengths of this exam are that by achieving maximum distension spasm can be differentiated from strictures, and that double contrast visualization of the terminal ileal mucosa is achieved. Apthous ulcers can be detected. These findings can be particularly useful after ileocolic anastomosis, where there is generally some nonspecific inflammation at endoscopy and hyperenhancement at cross-sectional enterography (Fig. 3.9). Peroral pneumocolon is probably the best method to assess for mucosal inflammation at fluoroscopy in the presence of an ileocolic anastomosis, as air is easily refluxed into the distal small bowel.

Fig. 3.9

Left panel: Crohn’s patient with prior right hemicolectomy and ileoascending anastomosis (arrowheads) at CT enterography, with questionable mural hyperenhancement in the neoterminal ileum (black arrows). Right panel: Peroral pneumocolon nicely demonstrates the anastomosis (white arrow), and normal appearing ileal mucosa. Patient treatment remained unchanged as a result of peroral pneumocolon

There are several weaknesses of the SBFT, which should be considered. As mentioned, there is a sensitivity penalty in not performing cross-sectional enterography [14, 16], but in the presence of low probability of disease, the SBFT can add substantial confidence to ileocolonoscopy in making the correct diagnosis [18]. Mild jejunal disease can still be challenging, but moderate and advanced inflammation can be reliably detected. Unlike cross-sectional enterography, the mesentery, colon, anus, and appendix are not imaged, so the SBFT alone cannot reliably stage the full extent of Crohn’s involvement along the GI tract. Additionally, to detect penetrating disease by SBFT, barium must fill sinus tracts or fistulae. In contradistinction, fistulae and sinus tracts at cross-sectional enterography often do not contain enteric contrast but are easily recognized as enhancing, extraenteric tracts that stand out from the surrounding mesenteric fat and which cause tethering of involved small bowel loops [15, 17, 20]. The SBFT can be performed in patients with a small bowel obstruction but is rarely needed and is often unfruitful owing to the time required for examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree