Flexible Sigmoidoscopy and Colonoscopy

Chris E. Lascarides

One look is worth a thousand listens.

—APHORISM

The ability to visualize the colon, rectum, and anus has essentially paralleled the precision with which the surgeon has been able to diagnose and treat individuals with diseases of this area of the digestive tract. In the mid-19th century, visualization was accomplished by means of a hollow tube illuminated by a candle and focused with a parabolic mirror. However, examination of the entire colon had not been possible prior to the introduction of x-rays (see Chapter 5). Although improved radiologic techniques facilitated the accuracy of colonic diagnoses, distal bowel visualization was limited to that which could be accomplished with the rigid proctosigmoidoscope. Illumination was provided by a lightbulb within the instrument or directed to the tip by means of straight fibers (see Chapter 5).

The origin of flexible endoscopy of the colon began with the introduction of semirigid and then flexible upper gastrointestinal instruments (esophagogastroscopy). Hopkins and Kapany are generally credited with describing the initial flexible fiberscope, in 1954.84 Subsequently, a major improvement in the quality of light transmission was made with the establishment of a glass-coated fiber that permitted the transmission of illumination along nonlinear paths. When combined with a similar fiber bundle whose orientation was preserved, the illuminated image could be transmitted back to the observer. Initially, the technology was applied to the stomach, but this was quickly adapted to the colon. Short, flexible fiberoptic instrument examinations of the rectum and distal colon were performed, but soon longer instruments were developed, usually with the use of gastroscopes applied to the bowel. It came to be appreciated, however, that successful colonic examination often required more forceful manipulation than was necessary for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Consequently, the later versions of the colonoscope that evolved were longer and more robust (see later).

A later advance in instrumentation has been the introduction of videoendoscopy. The image-transmitting fiberoptic bundle has been replaced by a charged coupled device that provides an electronic image of the field of view. The examiner no longer has to contend with broken fiber bundles and progressive degradation of the endoscopic picture. Furthermore, the endoscopist no longer needs to squint into the lens at the end of the instrument but can instead work directly from a high-resolution monitor. In addition, the digitized image can be handled like any electronic file: stored, printed, and annotated. This has proved to be a clearly superior method of record keeping and documentation.

▶ FLEXIBLE FIBEROPTIC SIGMOIDOSCOPY AND VIDEOENDOSCOPY

The term endoscope is derived from two Greek words: endon, meaning within, and skopein, to view. With the fiberoptic sigmoidoscope, the diameters of the individual glass fibers in the image-conveying aligned bundles are similar, ranging from 9 to 12 µm.50 The individual fibers are bound together at their ends, whereas the rest of the fibers remain loose and flexible. The fiberoptic endoscope can be made as long as necessary because light loss is negligible over several meters.50

There is no doubt that flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) inspects more bowel surface area than is possible with the rigid proctosigmoidoscope. Marks and associates reached 50 cm or more in approximately two-thirds of their patients.107 The overall yield of pathology was more than three times greater with the flexible instrument. Wherry and Thomas recruited more than 4,000 asymptomatic patients in a screening program using FS.171 Eleven carcinomas were detected, an overall rate of 3.2 per 1,000 subjects screened. Others also report considerable satisfaction in this regard,14,21,59,134,174 but the length of bowel examined is often considerably less than it might appear. For example, Lehman and colleagues determined the anatomic extent of insertion by placing a clip on the bowel mucosa and subsequently identifying that point on a barium enema study.101 A so-called 60-cm examination viewed the entire sigmoid in only 81% of patients. It is also important to recognize that if an individual were to undergo subsequent barium enema study, regardless of the endoscopic findings, there would be no appreciable difference between rigid proctosigmoidoscopy and FS in the incidence of detection of neoplasms.152 This presupposes, of course, that the barium enema examination is of optimal quality (see Chapter 5).

FS is not a simple examination to master. The most difficult part of colonoscopy is negotiation of the sigmoid colon, and this problem pertains equally to FS; the only difference perhaps is that the physician does not usually employ various straightening maneuvers, although this can be accomplished if necessary (see Colonoscopy). The examination requires skill and patience, and there is no substitute for experience. To paraphrase Hedberg, “If only we could omit the first 100 endoscopies and begin with number 101, a more comprehensive examination would be obtained, and we would experience very few complications indeed” (S. E. Hedberg, personal communication,).

In addressing the assertion that the procedure is more comfortable than rigid proctosigmoidoscopy, this may be more a reflection of patient position than of the examination. As mentioned in Chapter 5, the lateral Sims’ position is preferred for patient comfort, and this is the recommended approach for FS. The examination does, however, take longer; approximately one-half of the procedures took more than 5 minutes in a series by Marks and associates.107 It has been shown, in fact, that women who have undergone hysterectomy have more difficult, painful, and more limited examinations.4 Analgesia (i.e., conscious sedation) should perhaps be considered in this group of patients. With excessive air insufflation, gas cramping tends to persist for a much longer period following FS. The list here illustrates some real and theoretical disadvantages to this examination:

Cost | |

Capital expense and repairs | |

Personnel time for enema administration and/or bowel cleansing | |

Duration | |

Communicable disease | |

Complications | |

Perforation | |

Hemorrhage with concomitant procedure | |

Explosion with electrocautery | |

Infection | |

Compromise of adequate colon examination when colonoscopy is indicated | |

The first and most often quoted criticism of the technique is the cost of the equipment, which may exceed $15,000, including light source and accessories. In addition to the outlay for the capital expense and repairs, there are the costs of personnel (e.g., longer time for examination, need for cleansing the instrument, patient preparation). Of course, a critical consideration is the cost to the patient. In polling numerous medical centers and physicians, the fee for the examination ranged from a minimum of 25% more than for rigid proctosigmoidoscopy to as much as 200% more.

FS is an advance over rigid proctosigmoidoscopy as a screening tool, but it is not a substitute for colonic assessment. When a complete evaluation of the colon is indicated, such as when occult blood is present or when polyps have been documented, colonoscopy is the requisite procedure. There is, however, a place for rigid sigmoidoscopy. This technique is often preferred when a large biopsy is required, when a distal anastomosis needs to be visualized, when a culture needs to be obtained, or when an inflammatory disease is confined to the rectum.

FS is indicated in the following situations:

As a substitute for rigid proctosigmoidoscopy in screening, in evaluation of gastrointestinal complaints, and in interim polyp and cancer surveillance between colonoscopic examinations for distal disease

For evaluation of questionable radiologic findings in the sigmoid colon

For confirmation of radiographic findings within range of the instrument

For diagnostic and follow-up evaluation of a patient with inflammatory bowel disease, especially if the disease is confined to the left or distal colon

For inspection of colon anastomosis when it is within range of the instrument

Therapeutically, FS may be employed to reduce sigmoid volvulus and in combination with the snare to remove a foreign body. Absolute contraindications to this examination include fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, peritonitis, and acute diverticulitis. A poorly prepared bowel and an uncooperative patient are certainly limiting factors.

Instrumentation

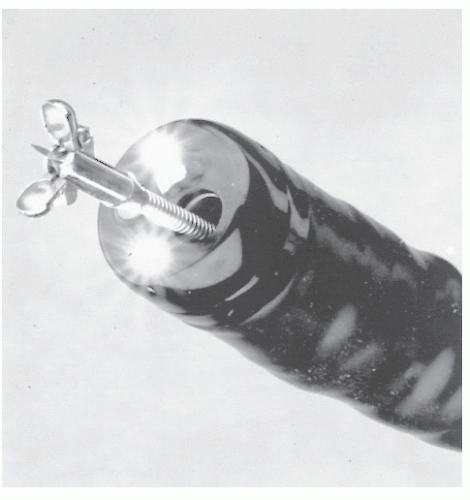

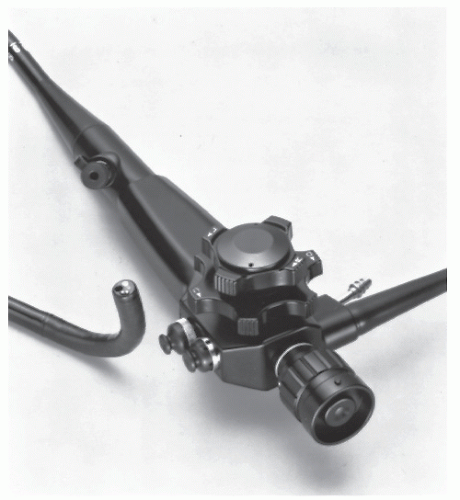

The flexible fiberoptic sigmoidoscope is available in the United States through several companies (Olympus America [Melville, NY], Pentax [Orangeburg, NY], Fujinon [Wayne, NJ], and Vision Sciences [Natick, MA]). The specifications of the instruments vary somewhat among the manufacturers. Generally, the channel size ranges between 2.6 and 3.8 mm, the instrument diameter varies from 12.2 to 14.0 mm, and lengths range from 60 to 71 cm. Figure 6-1 illustrates a flexible fiberoptic sigmoidoscope, and a close-up view of the bending section is shown in Figure 6-2. Biopsy forceps, a cytology brush, or a snare and electrocautery may be passed through the working channel (Figure 6-3). The tip of the instrument is deflected by rotation of the larger dial in each direction (Figure 6-4). The smaller dial deflects the tip from side to side. If both dials are turned maximally, it produces a tight bend that causes the instrument to double back and impede further passage. When passing the instrument, it is advantageous to keep the dials in the neutral position as much as possible (see Colonoscopy).

FIGURE 6-1. Pentax slim model (11.5-mm diameter) fiberoptic sigmoidoscope (model FS-34P2) with 70-cm working length. (Courtesy of Pentax Precision Instrument Corp., Orangeburg, NY.) |

The 35-cm flexible instrument should be mentioned, especially regarding the relative merits of this shorter diagnostic endoscope. As a tool for screening, there seems to be little difference between the two fiberoptic instruments with respect to identification of neoplasms.48,74 Furthermore, patients report that examination with the shorter instrument is, not surprisingly, more comfortable. I see, however, no great advantage in limiting the area of colon to be screened, and, in fact, with increased experience of the examiner, the length of time to perform the procedure should not be significantly different. The 35-cm flexible sigmoidoscope will in all probability be employed almost exclusively by the nonsurgeon and nonspecialist endoscopist.

Preparation

The use of FS requires only a limited bowel preparation. Two small enemas (e.g., Fleet) are given separately, the second approximately 10 minutes after the first has been eliminated. Dietary restrictions and oral laxatives are generally unnecessary. In some cases, oral preparations may be beneficial.

Technique

The patient is placed in the left lateral (Sims’ position) on a relatively high-examining table. The patient’s right leg is flexed more than the left, and the right shoulder is rotated anteriorly. It is usually easier for the physician to stand than to sit. Some physicians prefer a two-person team approach: one to handle the dials and the other to advance the instrument. Members of this school believe that in this way the procedure can be carried out much more expeditiously. This approach requires the use of a fiberoptic teaching attachment or videoendoscope (Figure 6-5). Conversely, most individuals believe that a single person should maneuver the dials with one hand and guide the instrument with the other, thereby permitting a more facile straightening maneuver. As a consequence, this may offer a more comfortable experience for the patient. The concept of discomfort has been addressed in a paper by Palakanis and colleagues on the effect of music therapy with individuals undergoing FS.129 Not surprisingly, the authors discovered that those who listened to self-selected music tapes during the procedure had significantly decreased anxiety inventory measurements (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory). Furthermore, they had statistically significantly reduced heart rates and decreased arterial blood pressures in comparison with control subjects. The authors concluded that music

is a very effective anxiolytic for the patient who undergoes FS.129

is a very effective anxiolytic for the patient who undergoes FS.129

A well-lubricated finger is passed into the rectum, and then the instrument is inserted. Passing the blunt-ended endoscope through the anal canal without prior digital examination is difficult to accomplish and leads to considerable apprehension and discomfort for the patient.

What is usually encountered initially is a dull pink or orange haze, perhaps with some fecal debris or retained enema fluid. While insufflating air rather than redirecting the tip, the examiner passes the instrument to a depth of 10 or 12 cm. This will permit visualization of the rectal ampulla.

The instrument is passed with the lumen seen either under direct visualization or with the mucosa seen sliding past. Again, the endoscopist can judge how firmly to push while watching the mucosa rush by. This approach is quite similar to that applicable to rigid proctosigmoidoscopy, but this maneuver is not preferable to luminal visualization and must be undertaken with great caution.

If further passage is impeded, the instrument is withdrawn slightly, the lumen is searched out by dial manipulation and rotation, and the instrument is advanced again. Coller has described in detail various methods helpful in advancing the instrument. He calls them torquing, dithering, and dither-torquing (i.e., accordionization; see later).32 By using the approach of dithering—the principle by which a person sitting on a chair with feet raised can move it across the floor through abrupt, jerking motions of the body—staccato movements of the instrument forward and backward may permit the bowel virtually to intubate itself onto the instrument.32

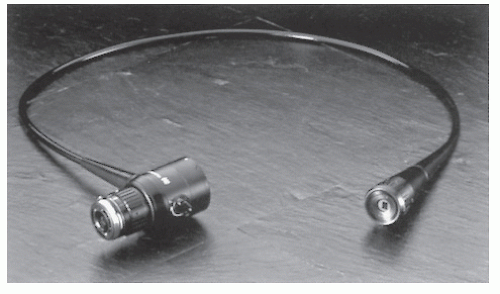

FIGURE 6-5. Fiberoptic teaching attachment, model LS-10. (Courtesy of Olympus America, Melville, NY.) |

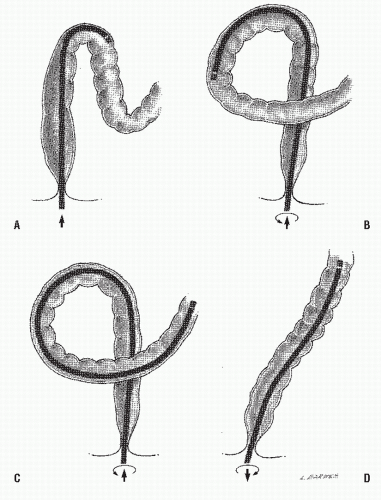

Negotiation of the sigmoid colon is the most difficult part of the procedure. With an intended limited examination, straightening the sigmoid is, perhaps, of less importance than it is with colonoscopy. If all the physician accomplishes, however, is to stretch the colon through attempts at advancement, another maneuver must be tried. Counterclockwise rotation of the instrument produces the alpha loop (Figure 6-6). Clockwise rotation results in relative straightening of the sigmoid and the opportunity to advance the instrument into the descending colon. Sedation may be required to accomplish this, but this is usually not available for office examination. Another means of proceeding into the descending colon when the sigmoid loop has already been traversed is to withdraw the instrument while rotating it clockwise.

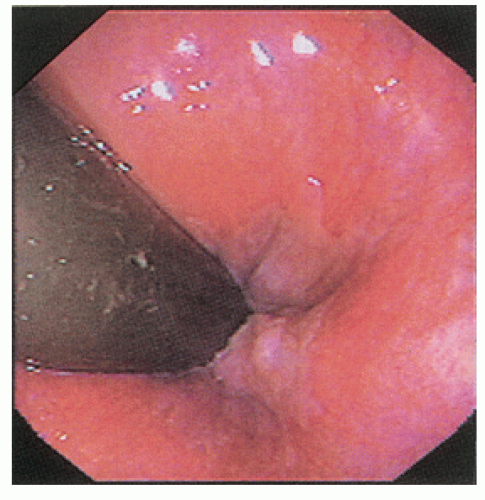

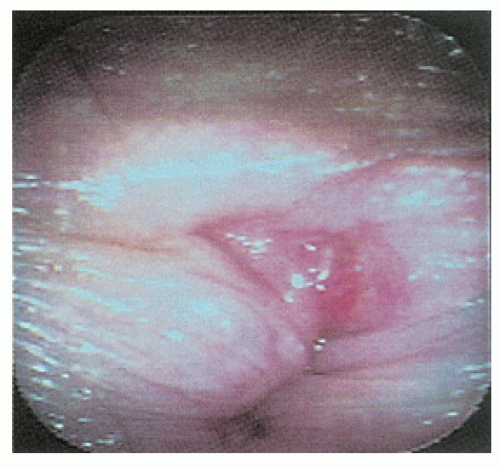

After the instrument has been passed to its full length or as far as is possible, it is carefully and slowly withdrawn. Suction, irrigation, and air insufflation are alternately employed as indicated to obtain clear visualization of the entire mucosa. Biopsy without electrocoagulation or brush cytology is obtained if appropriate, and the instrument is removed. It is important to remember that FS and colonoscopy are suboptimal tools for evaluation of ampullary or distal rectal disorders. Particular care is required for examination of this area, and retroflexion is strongly recommended as the ultimate maneuver (Figure 6-7).

Rectal Retroflexion

The importance of rectal retroflexion (RR) has been emphasized by Hanson and colleagues.78 They compared 480 patients who had undergone FS without RR with a subsequent examination wherein RR was employed routinely. Discomfort precluded completion of this maneuver in 3.5%. There was a 1% increased yield of identifiable adenomas when RR was performed.78

The technique for accomplishing RR has been well described78:

Advance the shaft approximately 10 cm above the mucocutaneous junction.

Maximally deflect the shaft upward.

Advance the instrument an additional 5 to 10 cm against the rectal fold.

Rotate the retroflexed shaft to view the circumference of the anorectal junction.

Finally, the physician must not forget why the examination was being performed in the first instance. If bleeding were the indication, it is not sufficient to reassure the patient that FS was normal. Furthermore, the flexible sigmoidoscope is not the optimal tool for diagnosing pruritus ani, hemorrhoids, or fissure and obviously is not the ideal instrument for evaluating the anal canal (Figure 6-8). Anoscopy and additional studies may be required.

Gastroenterologists, however, because they do not generally perform anoscopy, seem quite comfortable with using FS and colonoscopy with RR as a diagnostic instrument for anal disorders. Although this is the standard of care for this specialty, anal lesions can be missed or misinterpreted if anoscopy is not performed when certain anal problems are suspected.

Gastroenterologists, however, because they do not generally perform anoscopy, seem quite comfortable with using FS and colonoscopy with RR as a diagnostic instrument for anal disorders. Although this is the standard of care for this specialty, anal lesions can be missed or misinterpreted if anoscopy is not performed when certain anal problems are suspected.

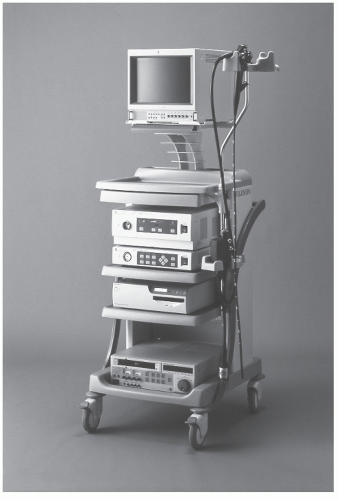

Videoendoscopy

In 1983, the Welch Allyn Corporation (Skaneateles Falls, NY) introduced a special feature for viewing the gastrointestinal tract, the videoendoscope. The endoscopic images are transmitted by a small electronic chip known as a charged coupled device.142 Other companies have since entered the field, each producing video screen imagery with the ability to videotape examinations; to produce remote hard copy; and, of course, to serve as an excellent teaching modality (Figure 6-9). Information can be displayed on the monitor (i.e., patient’s name, physician’s name, pertinent history) to create a useful database for retrieval purposes.148 Figure 6-10 shows the basic equipment. With the cost in excess of $75,000, this method is employed primarily in teaching centers and in endoscopy units, especially wherein there are numbers of patients sufficient to justify considerable capital investment. An attachment for converting the fiberoptic output to a video screen is also available (Figure 6-11). Their principles of passage are identical to those of FS with the fiberoptic instrument.

Complications of Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Complications such as hemorrhage or perforation should not occur with any greater frequency with a flexible instrument than with the rigid, especially if the examiner does not force its passage—at least there are no randomized, clinical trials that demonstrate a difference. However, if an alpha or a straightening maneuver is undertaken, it is possible for the sigmoid colon to be torn and a perforation to occur. Attention to limiting patient discomfort is therefore an important concern. Furthermore, caution is obviously required whenever the procedure is undertaken in the presence of bowel disease. Depending on the acuteness of the process, especially with active inflammation, diverticulitis, or ischemia, FS may be

contraindicated. Minimal air should be used when inflammation is present. Care should also be observed, especially with respect to insufflation of air, when an individual has a known inguinal hernia. Incarceration and obstruction of a herniated sigmoid colon from overdistension has been reported.172 Explosions should not occur because electrocautery should not be employed for biopsy or snare excision with this instrument, unless a full bowel preparation has been used. The limited bowel preparation that is usually employed, combined with a closed system, presents a potential hazard for the presence of an explosive gas mixture. Biopsies should be carried out only with “cold” forceps. Brush cytology may, of course, be safely employed.

contraindicated. Minimal air should be used when inflammation is present. Care should also be observed, especially with respect to insufflation of air, when an individual has a known inguinal hernia. Incarceration and obstruction of a herniated sigmoid colon from overdistension has been reported.172 Explosions should not occur because electrocautery should not be employed for biopsy or snare excision with this instrument, unless a full bowel preparation has been used. The limited bowel preparation that is usually employed, combined with a closed system, presents a potential hazard for the presence of an explosive gas mixture. Biopsies should be carried out only with “cold” forceps. Brush cytology may, of course, be safely employed.

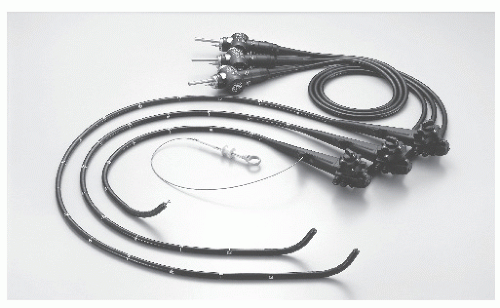

FIGURE 6-9. Videosigmoidoscope (73 cm [model CF-Q160S]) and videocolonoscopes (in two lengths: 133 cm [model CF-Q1601] and 168 cm [model CF-Q160L]). (Courtesy of Olympus America, Melville, NY.) |

▶ COLONOSCOPY

In 1969, fiberoptic colonoscopy was introduced as a means of directly visualizing the colon and rectum and, in many instances, even the terminal ileum. Within a few years, Wolff and Shinya demonstrated that by using a wire loop snare and electrocautery, polyps could be removed through the instrument, thus virtually rendering colotomy and polypectomy obsolete.175

WILLIAM IRWIN WOLFF (1916-2011)

|

William Wolff was born in New York City and attended the University of Maryland School of Medicine, where he received the Prize Gold Medal. He then entered the Cornell and Columbia residency program at Bellevue Hospital in New York, with his training interrupted by World War II. While serving in a field hospital in Belgium after the Normandy invasion, he barely escaped capture during the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he completed his residency at the Bronx Veterans Hospital in New York. As an attending surgeon at Cornell Division at Bellevue, he developed a research facility and an open-heart surgery program. In 1962, he became the first full-time director of surgery at the Beth Israel Medical Center in New York and professor of surgery at the new Mount Sinai School of Medicine. In the mid-1960s, he and his young associate, Hiromi Shinya, established an upper gastrointestinal fiberoptic endoscopic laboratory and clinical facility. Their work led to the development of the first flexible instruments for evaluating the entire colon. After a successful study, the era of colonoscopy and colonoscopic polypectomy was born. Their efforts resulted in what Francis Moore described as a “quantum advance in surgery.” Their article was, in fact, selected by members of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons as among the top 11 literature contributions to 20th century colon and rectal surgery.37 A founding member of the Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons, Wolff received the highest award given to an alumnus of his alma mater, the University of Maryland, for “outstanding contributions to medicine and distinguished service to mankind.” He died at his home in Manhattan, August 20, 2011, in his 95th year.

HIROMI SHINYA (1935-PRESENT)

|

Hiromi Shinya was born in Yanagawa, Fukuoka prefecture, Japan, and completed his medical studies in 1960 at Tokyo’s Juntendo University. After his internship at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Yokosuka, he arrived in New York City to begin his general surgical residency at the Beth Israel Medical Center. In 1967, while still in his residency, he became interested in the newly evolving instrumentation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. As a consequence of this experience, he moved on to develop the technique for examination of the colon, devising many of the accessories, such as the snare cautery. In 1969, with the support and encouragement of his chief, William Wolff, he began a series of successful polypectomy procedures. Because of his unique experience and abilities, he received a special visa waiver by order of the president of the United States to remain in the country and to continue his work. His colonoscopy experience to date exceeds 250,000 patients.

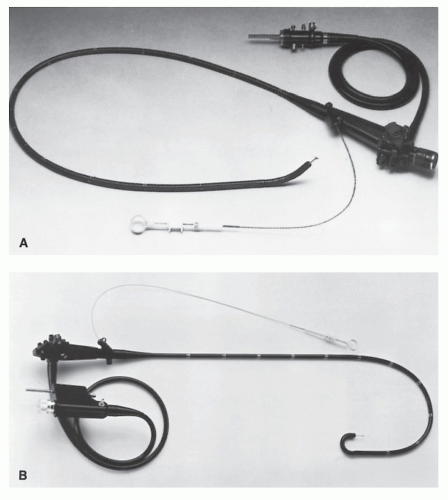

Instrumentation

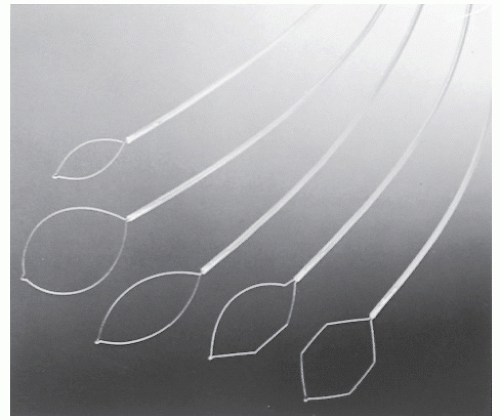

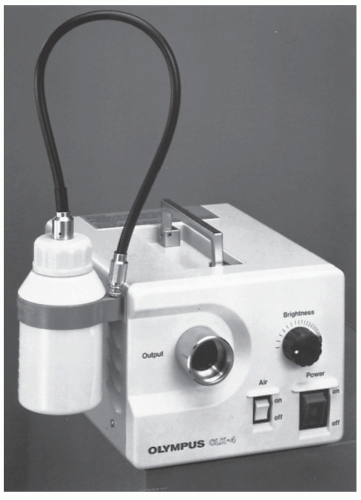

As mentioned earlier, there are numerous suppliers of colonoscopes in the United States, most of which use similar optical or video structures. The instruments vary mainly in length, total diameter, and maneuverability and have a number of accessories. Working lengths vary from approximately 115 cm to almost 180 cm. They are forward viewing and may offer a field of view up to 160 degrees (Figure 6-12). Newer endoscopic systems additionally offer high-definition output for an even higher level of clarity on compatible monitors. Some individuals prefer a twochannel system in order to use two accessories for treatment, including that of polypectomy (Figure 6-13). As with FS, four-way angulation of the distal end is achieved from approximately 180 degrees up or down and 160 degrees right and left by manipulating the control knobs (Figure 6-4). Additional features include an air outlet, a forward water jet channel, and a suction/forceps channel. Air or carbon dioxide can be insufflated and liquid debris removed during the procedure. Accessories include a halogen light source (Figure 6-14) and an electrosurgical unit (Figure 6-15), as well as photographic equipment. Requisite items for procedures include biopsy forceps, a diathermy

snare, and grasping forceps, in addition to an instrument for brush cytology.

snare, and grasping forceps, in addition to an instrument for brush cytology.

FIGURE 6-13. Two-channel therapeutic colonofiberscope (model FC-38TLH) features water jet. (Courtesy of Pentax Precision Instrument Corp., Orangeburg, NY.) |

FIGURE 6-14. This simplified 150-W halogen light source includes an air pump and water container with pipe. (Courtesy of Olympus America, Melville, NY.) |

Cost is also a major concern when contemplating the purchase of a colonoscope. The cost of a video colonoscope approximates $35,000. With all the accessories, the comprehensive unit could cost three times that amount. Repairs and the limited life expectancy of the instruments also must be considered in assessing the expense. However, there is universal agreement that, with the plethora of colon disorders in Western countries, especially neoplasms, colonoscopy and colonoscopy-polypectomy are among the most important advances for diagnosis and treatment to become available since the late 1960s.

Indications

It is generally agreed that colonoscopy has for the most part replaced the barium enema in the evaluation of colon disorders.1 The list here summarizes the indications for this procedure:

Confirmation or refutation of suspected or equivocal radiologic abnormality (e.g., filling defects, narrowing [intrinsic vs. extrinsic lesion], polyps)

Evaluation and follow-up of inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., dysplasia)

Differential diagnosis of diverticular disease and malignancy

Presence of a rectal polyp with or without barium enema abnormality (e.g., synchronous lesions)

Gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., bleeding, abdominal pain, iron-deficiency anemia) with or without radiologic investigation failing to reveal the source

Follow-up evaluation of patient with prior colon surgery

Colon and rectal cancer screening

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Clinically significant diarrhea of unexplained origin

Endoscopic polypectomy

Reduction of sigmoid volvulus

Decompression of dilated colon (e.g., Ogilvie’s syndrome)

Intraoperative colonoscopy; confirmation of location of lesion at time of laparotomy or during laparoscopic procedures

Colonoscopic percutaneous colostomy

In some instances, the procedure is employed either because the barium enema study or virtual colonoscopy demonstrates a possible abnormality or because other investigations fail to indicate or identify the source when symptoms suggest colonic disease.34 In two reports analyzing the results of unexplained rectal bleeding, 30% of the patients were found to have significant lesions in spite of a normal barium enema examination.16,160 Needless to state, however, that colonoscopic procedures are usually carried out without the patient having undergone a prior contrast study.

Colonoscopy has been demonstrated to be of diagnostic usefulness in a host of clinical situations (e.g., screening for colorectal cancer, diverticular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, pseudomembranous colitis, and unexplained rectal bleeding, to name only a few; see endoscopic photographs that appear throughout this text).13,16,17,41,43,58,61,67,76,83,97,104,113,118,149,156,159,160,164 Other conditions for which diagnosis has been confirmed or expedited by colonoscopy include amebic colitis, intestinal tuberculosis, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, and radiation colitis.34,42,153

Diagnostic colonoscopy is generally not appropriate for chronic, stable, irritable bowel complaints, in acute limited diarrhea, when bleeding is readily observed to come from an obvious source (e.g., fissure, hemorrhoids, peptic ulcer) and when patient management would be unaffected by the findings (e.g., metastatic carcinoma in the absence of bowel symptoms).

Contraindications and Concerns

Absolute contraindications to this examination are essentially limited to those patients with an acute cardiovascular problem (e.g., unstable angina, myocardial infarction) and those with an acute abdominal inflammation (e.g., peritonitis), acute diverticulitis, fulminant colitis, bowel perforation, and toxic megacolon. Relative contraindications include the last two trimesters of pregnancy, pregnancy at any stage if fluoroscopy is to be employed, marked splenomegaly, and an abdominal aortic aneurysm.33

Aspirin

Traditional teaching is to withhold aspirin 7 days prior to colonoscopy because of the concern for bleeding. Ker and colleagues challenged this concept by prospectively randomizing 205 patients to receive 650 mg of aspirin for 10 days prior to colonoscopy with biopsy or polypectomy or not to receive the drug.94 The bleeding time was marginally prolonged in the former group, the platelet count was not affected, and there was no increased incidence of bleeding. The authors concluded that aspirin can be safely continued in preparation for colonoscopy.94

Anticoagulation

Patients who may be at a risk for bleeding because of a possible blood dyscrasia should undergo coagulation studies prior to colonoscopy. Those receiving the anticoagulant sodium warfarin (Coumadin) should ideally have the medication discontinued prior to the procedure.33 Caliendo and coworkers performed a retrospective review of their patients with regard to anticoagulation.19 They observed that colonoscopy without

polypectomy may be performed safely without discontinuing therapy. However, resuming antiplatelet treatment immediately after colonoscopy-polypectomy was associated with a high risk of bleeding. There were no thromboembolic complications. Timothy and colleagues, also in a retrospective review involving 94 patients (109 examinations) on warfarin, noted that colonoscopy could be performed safely, but that there was a slightly increased incidence of hemorrhagic complications with biopsy or snare excision.162 Their recommended approach to the patient on warfarin who can tolerate a “period” of “normal” coagulation is as follows162:

polypectomy may be performed safely without discontinuing therapy. However, resuming antiplatelet treatment immediately after colonoscopy-polypectomy was associated with a high risk of bleeding. There were no thromboembolic complications. Timothy and colleagues, also in a retrospective review involving 94 patients (109 examinations) on warfarin, noted that colonoscopy could be performed safely, but that there was a slightly increased incidence of hemorrhagic complications with biopsy or snare excision.162 Their recommended approach to the patient on warfarin who can tolerate a “period” of “normal” coagulation is as follows162:

Stop warfarin for 3 days.

Obtain the prothrombin time/INR (international normalized ratio) prior to the procedure.

If the INR is less than 2, proceed with colonoscopy and restart warfarin (using prior dosage) on the first postoperative day.

If the INR is 2 or greater, postpone the procedure for 1 to 2 days or, alternatively, perform the diagnostic procedure and postpone restarting warfarin for 2 to 3 days if a therapeutic procedure is contemplated.

If a diagnostic procedure is performed, restart warfarin at the prior dose on postprocedure day 1.

Privileging and Credentialing

Wexner, Eisen, and Simmang, in 2002, prepared a consensus document concerning endoscopic privileging and credentialing that has been endorsed by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.170 They emphasized that the credentialing structure and process are the responsibility of the health care facility, and that uniform standards should be developed for performing specific endoscopic procedures regardless of the specialty in which an individual physician practices. Training may be accomplished through a formal surgery or gastroenterology residency program or through an equivalent “certification of experience by a skilled endoscopic practitioner.” Determination of competence requires the following:

Completion of a residency program with structured, documented experience in gastrointestinal endoscopy, or

Demonstrated proficiency in technique and clinical judgment equivalent to that which is obtained in a residency program, and

Confirmation in writing from the endoscopic director as to the applicant’s training, experience, and observed level of competency

The consensus document also incorporates statements on training in new techniques, proctoring of applicants for privileges, criteria for competency, monitoring of performance, requirement for continuing medical education, and the renewal of privileges.170

Preparation of the Patient

As with barium enema examination, the importance of an adequately cleansed colon cannot be overemphasized.157 There are two reasons for requiring a clean colon before proceeding with colonoscopic examination: safety and accuracy. The danger of causing injury when trying to intubate a feces-laden bowel is appreciable. The presence of formed stool may obscure the lumen and lead the endoscopist to apply forces in dangerous ways. Even a minor amount of stool can lead to confusion and misinterpretation. For example, a piece of stool that is firmly adherent to the lens may require removal of the instrument blindly and the necessity of starting all over again. When residual fecal matter is encountered, it is important to irrigate it free before passing on to other areas.

For most ambulatory patients, a vigorous cathartic followed by colonic irrigation or a small-volume enema (i.e., Fleet), along with appropriate dietary restriction, is generally satisfactory and can be commenced in the morning for an afternoon examination or in the evening prior to a morning endoscopy. However, sedentary or frail individuals may require several days to prepare the bowel adequately, especially if a less vigorous cleansing regimen is adopted. Care must be taken to maintain adequate fluid intake and to avoid electrolyte abnormalities because fluid loss may cause patients to lose as much as 7 lbs (3.2 kg).18,171 This is of particular concern in individuals with cardiovascular or renal disease.

Davis and colleagues devised an electrolyte solution containing primarily sodium sulfate with polyethylene glycol (PEG) as an additional osmotic agent (i.e., Golytely).40 Studies have been published that verify the safety and efficacy of this lavage method in preparation for colonoscopy and for barium enema examination, especially if bisacodyl (Dulcolax) is added to ensure evacuation of residual fluid.45,51,70,71 It has become, at least for endoscopists, if not for patients, the most popular preparation in the United States for colonoscopy.

The preparation can be administered orally or by tube feedings. A dose of 4 L is usually sufficient to produce adequate cleansing. The most frequent complaint about this method of cleansing the bowel and the primary drawback are the discomfort and distaste associated with consumption of such a large quantity of fluid. “The preparation was worse than the procedure” is a frequently voiced statement. Another PEG preparation, Colyte, has been made available in various flavors to deal with the difficulties associated with poor patient compliance.111

It is because of patient complaints that some have used another colon-cleansing technique in these individuals. Fleet Phospho-Soda was a common component of colonoscopy preparations replacing PEG in most preparations. It was not applicable for those with renal failure, ascites, congestive heart failure, a diversionary stoma, a history of myocardial infarction within 6 months, or those taking a calcium channel blocker such as nifedipine (Procardia) or verapamil (Calan). In December 2008, this preparation was recalled from the market because there were several cases of renal toxicity in patients with no risk factors for renal insufficiency. Some of these patients had such pronounced renal insufficiency that they required hemodialysis and renal transplantation. It has been removed from general use in the preparation of patients undergoing colonoscopy and should not be prescribed.

Alternative Preparations

Magnesium citrate is an alternative preparation that was used as an intermediate volume preparation between the 1 gal PEG solutions and the 45-mL Fleet Phospho-Soda preps. This involves using two 10-oz bottles of magnesium citrate on the day prior to colonoscopy. It can be an effective preparation but carries some of the same electrolyte risks as the Fleet preparation and should not be used in patients with the previously detailed clinical conditions. Various other manufactures have come to market with alternative cleansing solutions, such as HalfLytely and MoviPrep (PEG + ascorbic acid).

They are all more or less based on PEG-type compounds, and one generally varies the volume used to cleanse the bowel. A common preparation in practice with gastroenterologists involves the use of Miralax, a tasteless laxative in powder form used in the treatment of constipation. It is often used in an off-label manor, with 238 g mixed with 64 oz of clear liquids, such as a sports drink or apple juice. This has supplanted Fleet Phospho-Soda as the preparation used in patients concerned about the taste of the preparation. Once again, use of this Miralax-based preparation is off of the FDA-approved label.

They are all more or less based on PEG-type compounds, and one generally varies the volume used to cleanse the bowel. A common preparation in practice with gastroenterologists involves the use of Miralax, a tasteless laxative in powder form used in the treatment of constipation. It is often used in an off-label manor, with 238 g mixed with 64 oz of clear liquids, such as a sports drink or apple juice. This has supplanted Fleet Phospho-Soda as the preparation used in patients concerned about the taste of the preparation. Once again, use of this Miralax-based preparation is off of the FDA-approved label.

Timing of Preparations

It has been demonstrated that more important than the type of preparation used for bowel cleansing is the timing of administration. Traditionally, colonoscopy preparations have been administered as a single dose or in a divide dose on the evening prior to colonoscopy. Numerous recent studies have linked the quality of bowel cleansing, specifically of the right colon with “split-dose” regimens in which the second dose is given on the morning prior to the procedure.108,130

It has been deemed by many that the standard of care should include a colonic preparation when the second dose of laxative is begun 4 to 5 hours prior to the colonoscopy time and completed within 2 hours of the time of the procedure.

Sedation and Monitoring

Sedation with monitoring is usually employed whenever total colonoscopy is undertaken. The insufflation of air or carbon dioxide—the latter is more rapidly absorbed—and traction on the bowel from the instrument may cause considerable discomfort and anxiety. It is important for the examiner to be aware of any excessive discomfort that the patient is experiencing in order to avoid possible injury to the bowel wall, mesentery, or adjoining structures.

Certain combinations of medications have been advised to reduce discomfort, including meperidine hydrochloride (Demerol), fentanyl, diazepam (Valium), and midazolam (Versed).34 Irrespective of the choice of medication, a heparin lock is recommended for intravenous access and is generally required by standardized conscious sedation regulations. Several publications have appeared cautioning one as to the risks of oversedation and the requirement for continuous monitoring, including electrocardiogram, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, nasal airflow by thermistor probe, and impedance pneumography.79 Care should be taken to avoid respiratory depression and hypotension; elderly patients and those with respiratory and pulmonary difficulties are at particular risk. The most frequently employed monitoring device is the pulse oximeter, a method that provides continuous noninvasive measurement of arterial hemoglobin and oxygen saturation.

One of the real concerns about monitoring has been the cost. A manual sphygmomanometer is about $150; automatic pressure monitor, $3,000; electrocardiographic monitoring systems, $5,000 to $6,000; and pulse oximeters, $2,000 to $5,000.56 Some recommendations concerning monitoring for conscious sedation have been offered by Fleischer.56 However, there are no controlled studies that address the question of whether noninvasive monitoring decreases the incidence of complications. These guidelines have been fairly standardized and established at all hospitals and endoscopy centers. They generally include the following56:

Monitoring should be part of the overall quality assurance program for the endoscopy unit.

A competent assistant is the most important part of the monitoring process.

The amount of monitoring should be proportional to the risk of the procedure for that individual.

Minimal monitoring should include heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate prior to, during, and immediately after the procedure and when the individual is about to leave the room.

The requirement for sedation or analgesic medication must, perforce, be related to the technical facility of the examiner.

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has published a protocol for sedation and monitoring of patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. This is worth quoting:

Every available means to ensure the safety of patients during endoscopic procedures is mandatory. This begins with a fully trained and knowledgeable endoscopist, thorough preparation of the unit to handle endoscopic procedures and potential adverse outcomes, appropriate patient preparation, skilled assistants, and monitoring of the patient’s well-being before, during, and after the procedure.

The relative risks involved can be estimated from patient and procedural factors and should be determined for each examination. The level and type of monitoring during endoscopic procedures are dependent on a thorough understanding and assessment of the risk to the patient.

Monitoring of patients undergoing endoscopic procedures is mandatory and prudent. The ultimate responsibility for protecting the patient rests with the endoscopist and cannot be assigned to an assistant or to an electronic monitoring device. However, both may greatly improve the ability to detect patient distress at a time when intervention will prevent an otherwise adverse outcome.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Technique of Examination: General Principles

If you don’t know where you are going, all roads will get you there.

—Koran

Most colonoscopies require at least a modest amount of manipulation, and many are truly challenging. It is particularly important that the endoscopist has a thorough understanding of the interaction between a relatively unforgiving instrument and the variably compliant colon. Furthermore, a clear understanding of colonic anatomy is essential. For example, it is fixed at the rectum and is usually attached to the retroperitoneum at the descending, cecal, and ascending portions. Other areas, such as the hepatic and splenic flexures, although not fixed in the abdominal cavity, are intimately related to adjacent structures. Certain parts, notably the sigmoid and transverse colon, may have considerable mobility, being tethered only by the mesentery. Each portion of the colon has its own individual compliance. Successful intubation is in great part dependent on taking advantage of this compliance as well as overcoming the varied obstacles to passage.

There are certain properties of the colonoscope and maneuvers that must be employed in order to accomplish successful intubation. These include tip deflection, shaft torquing, and shaft dithering. These physical movements of the instrument are combined with air insufflation, deflation, patient positioning, and abdominal pressure.

Tip Deflection

The articulating deflection tip is the most critical element in the design of the colonoscope. The ability to move the viewing tip off center by more than 180 degrees in any direction enables the examiner to have active control of what happens at the far end of the instrument. Deflection permits the endoscopist to look around a bend or fold in order to see in just which direction one needs to proceed. Folds can be pressed against the wall so that small lesions, which would otherwise stay hidden, are exposed. This articulation is essential during therapeutic maneuvers in order to aim a snare or biopsy forceps in the proper direction. In selected instances, the deflection tip may be retroflexed in order to obtain a clearer view of an obscured area such as the top of the anal canal (Figure 6-7) or the cecal side of the ileocecal valve (see Figures 6-21 and 6-22 later).

The articulating deflection tip, as essential as it is to facilitating intubation, may at the same time be the single greatest impediment to successful passage, at least for the novice colonoscopist. As the tip is deflected from the straight position, a gentle curve forms along the distal 10 to 12 cm. With a relatively modest bend of 30 to 45 degrees, an advancement of the instrument shaft will not distort the contour of the colon. However, when one attempts to increase the deflection to more than 90 degrees, in an effort to see around a curve or angle of the bowel, the distribution of forces against the colon wall changes profoundly. In the latter situation, a greater proportion of the advancing force is distributed against the sidewall of the bowel rather than in the forward direction of the lumen. In addition, the application of extreme deflection to both knob controls further deviates force distribution and precludes all attempts at advancement. Longitudinal advancement of the scope no longer follows the tip of the instrument. Instead, the deflection bend now becomes the leading edge of the instrument, with forward force transmitted directly to the wall of the colon. As a consequence, blunt or tearing trauma can easily occur. This can take the form of splitting of the fibers of the muscle wall or frank perforation. The operator can avoid this complication by simply recognizing that extreme deflection is being employed, and that with attempted instrument advancement, the bowel under view seems to be getting further away rather than closer. Occasionally, extreme deflection is required in order to find the lumen. But once identified, the deflection should be eased, preferably to less than 90 degrees before attempting further advancement of the scope.

In summary, the least amount of deflection that is necessary in order to acquire the desired view is preferred. Limiting deflection to the use of the up-down dial only, while abjuring the simultaneous application of both controls, is helpful for minimizing inappropriate deflection.

Shaft Torquing

Torquing is an essential maneuver for effective intubation as well as for optimal surface visualization during extubation. Shaft torquing can produce three major effects. When left-handed or counterclockwise torque is applied, there is a tendency to produce a loop in the redundant sigmoid colon. Second, if clockwise torque is applied, the sigmoid colon tends to straighten. The third effect is produced at the tip of the scope. When the shaft is torqued in either direction in the presence of modest tip deflection, strong leverage is transmitted toward the entrance to the more proximal bowel. Using torque with modest tip deflection is generally more effective in locating an elusive proximal segment, as opposed to holding the shaft rigid while manipulating the deflection tip alone.

As more instrument is introduced, the response to torquing becomes more complex. If the scope is relatively straight, the torque will transmit nearly one to one to the viewing lens of the instrument. The field of view will simply be rotated; this facilitates identification of lesions or positioning of snares. However, if the scope shaft is within one or more loops, the results of torquing will have a much more profound effect on the bowel than on what is perceived through the viewing end of the instrument. If there is a so-called alpha loop present in the sigmoid colon, the effect of clockwise torquing (especially when combined with shaft withdrawal) is to reduce that loop by accordionizing the bowel onto the scope. This occurs without loss of intubation distance. However, once reduced, the sigmoid loop will have a tendency to form again, particularly if counterclockwise torque is applied during subsequent scope advancement. Therefore, in order to maintain reduction of a redundant sigmoid loop, one must advance the instrument while maintaining clockwise torque. The examiner can readily perceive this tendency to form the loop again by applying clockwise torque; the scope will appear to advance. Counterclockwise movement will reveal that the scope tends to lose ground.

Occasionally, an extremely redundant sigmoid colon will develop two complete loops during intubation. Nearly always, both are reducible. However, unlike the single-loop configuration, the first loop is removed by counterclockwise rotation and the second by clockwise rotation. Removing both loops is usually essential before proximal passage into the descending colon can be accomplished. After both loops have been straightened, the sigmoid colon is once again most likely to remain in this position only if clockwise torque is continued during further intubation.

Torque is also a very important maneuver in manipulations in the area of the hepatic flexure. If the transverse colon is held in the upper abdomen, the scope takes a straight line to the hepatic flexure. At this point, clockwise torque is usually beneficial as the gently deflected tip is directed down the ascending colon. Conversely, if the transverse colon is redundant, stretching down toward the pelvis, the hepatic flexure is then approached from below. When the ascending colon is viewed in this situation, there is a rather sharp deflection of the tip. Once again, gentle scope withdrawal along with clockwise torquing, as well as intermittent desufflation, all combine to broaden the hepatic flexure and to drop the instrument down into the ascending colon and cecum.

During extubation, torquing is an extremely important manipulation for efficient and thorough examination of the colon surface. As the instrument is withdrawn, the right hand is maintained on the shaft to apply torque. The left hand supports the scope head with the thumb free to move the up-down control. By combining back-and-forth torque with simultaneous small tip deflections, one can continuously examine the colon surface with minimal risk of overlooking

lesions. This permits the colon that has been accordionized onto the scope to be dropped off, a bit at a time. If, rather than torquing, one simply withdraws while using both hands of the dial controls, the view behind prominent folds is likely to be inadequate. Furthermore, if the colon is redundant, the bowel will likely fly off the scope at an uncontrollable rate.

lesions. This permits the colon that has been accordionized onto the scope to be dropped off, a bit at a time. If, rather than torquing, one simply withdraws while using both hands of the dial controls, the view behind prominent folds is likely to be inadequate. Furthermore, if the colon is redundant, the bowel will likely fly off the scope at an uncontrollable rate.

Advancement/Withdrawal (“Dithering”)

Colonoscopic intubation would be a simple matter if the colon were a noncompliant tube without redundancy or irregularity. The procedure would be nothing more than an effortless advancement of the instrument. On occasion, especially after sigmoid colon resection, colonoscopic intubation may be no more demanding than this. However, under most circumstances, the in-and-out movements of the shaft are only effective when combined with appropriate tip deflection and torquing. There is a tendency for the inexperienced endoscopist to resist losing ground even though it is unclear in which direction the scope should be advanced. Almost always, when anatomy is unclear or visualization is difficult, it is best and certainly safest to withdraw rather than to continue blind manipulation or advancement.169 The simple process of limited withdrawal is most likely to reveal the proper direction in which to proceed.

When progression of the instrument is not impeded by severe tip deflection, redundant colon can be encouraged to accordionize along its length. This is most likely to occur if the scope is repeatedly advanced and withdrawn, a process referred to as “dithering.” When combined with torquing in the sigmoid/descending colon, short dithering strokes can often reduce sigmoid redundancy as the scope is advanced, thereby avoiding the creation of a full loop. In less tethered segments, such as with a redundant transverse colon, it is often advantageous to perform long (30- to 50-cm) dithering strokes in order to accordionize the excess bowel onto a limited segment of instrument.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree