The evaluation of a colorectal complaint begins with the physical examination of the anus, rectum, and colon. The standard approach includes inspection, palpation, anoscopy, and proctosigmoidoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. These findings then dictate any further radiologic evaluation. Generally, the term proctosigmoidoscopy is used interchangeably with the words procto and sigmoidoscopy. All three imply the use of the 25-cm rigid instrument.

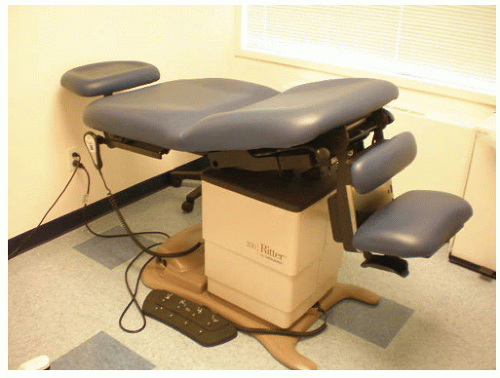

Positioning the Patient for Rigid Sigmoidoscopy

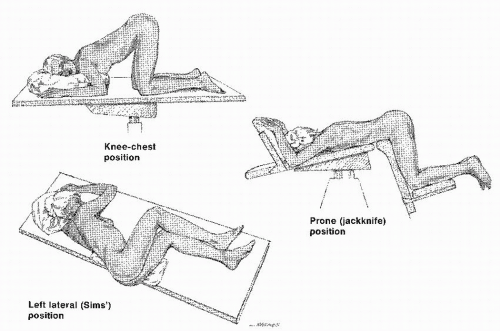

The technique for rigid sigmoidoscopy is becoming a lost skill as flexible sigmoidoscopy has become available in the outpatient setting. However, there are certain advantages to the rigid examination. For example, ironing out the rectal valves can be more readily accomplished with a rigid instrument. Therefore, a better visualization of areas that are potentially awkward to view may be achieved. In addition, the rigid instrument permits accurate measurement of the level of a lesion. Very often, use of the flexible instrument results in a measurement that is falsely higher than is truly the case. The most commonly used patient positions for performing sigmoidoscopy are the prone jackknife position and the left lateral position (

Figure 5-1).

The prone jackknife position requires a special table that tilts the patient’s head down (

Figure 5-2). The table is expensive, but it provides the easiest access and the best view for the examiner. It is the least comfortable position, however, for the patient.

The most comfortable position for an individual undergoing this examination is the left lateral (i.e., Sims’) position. The patient lies on the left side on the examining table or bed with the buttocks protruding over the edge, hips flexed, knees slightly extended, and right shoulder rotated anteriorly. The examiner may sit or stand depending on the height of the table or bed. Although this position is the easiest of the three for the patient, it is not as convenient for the examiner as is the prone position. Some physicians believe that the sigmoidoscope can be inserted farther when an individual is in one position rather than another, but there is no evidence to suggest that position either interferes with or facilitates insertion of the instrument to its full length.

If one is to perform a satisfactory and reasonably comfortable examination and obtain all necessary information, it is essential to inform the patient continually what is to be expected and

what is happening. Rectal examination may be a frustratingly unsuccessful experience for both the physician and the patient if proper concern is not demonstrated for the patient’s understandable reluctance to submit to such an unpleasant intrusion of the intestinal tract. Warm hands and a reassuring demeanor are most helpful. Additionally, a relaxed and supportive attitude with due consideration for the patient’s modesty is suggested, as is limiting the number of observers to no more than two.

31

Inspection

Inspection of the anal area may reveal hemorrhoids, skin tags, a sentinel pile indicative of an underlying anal fissure, dermatologic problems including pruritic changes, an abscess, a fistula, a scar, or a deformity. Evaluation of the sacrococcygeal region may disclose a laminectomy scar, possibly suggesting a neurologic cause for any incontinence symptoms.

116 Pain on spreading the buttocks may indicate the presence of an anal fissure.

In addition to mere inspection of the perianal skin, evaluation of the resting state of the anal opening is possible. A patulous anal orifice may be seen. This may be due to a concomitant rectal prolapse, neurologic abnormality, or sphincter injury, or it may be a sign of an anoreceptive person.

129By asking the patient to strain, additional valuable information may be obtained. A rectal prolapse; hypertrophied anal papilla; or, most commonly, hemorrhoids may protrude. It should be remembered, however, that the prone jackknife position is least conducive to demonstrating conditions that tend to prolapse. If the physician suspects procidentia, then the examination should be conducted while the patient sits and attempts to strain while sitting on the toilet or commode.

Palpation

A water-soluble lubricant is applied to the gloved index finger. The patient is informed that a finger will be passed into the rectum and that this will make him or her feel as if the bowels will move. Again, it is imperative to inform, distract, and reassure the patient continually. The physician should examine the rectum and its surrounding structures in an organized approach. Assessment of sphincter tone and contractility is an important part of the rectal examination, and these should be noted routinely whenever a patient complains of problems with fecal control or discharge. Digital rectal examination may serve as a rudimentary gauge of anal sphincter weakness or defects. In a study comparing findings of digital examination, anal manometry, and anal ultrasound, the authors found that digital examination correlated well with manometric findings, and was accurately able to detect large sphincter defects.

24In the male patient, the prostate is felt anteriorly. It should be assessed for hypertrophy, nodularity, and firmness. In the female patient, the cervix can be palpated, unless it is surgically absent. The uterine body may be felt to be displaced posteriorly, and the presence of fibroid tumors may be noted. The uninitiated examiner may misinterpret the uterus or cervix as being an intrarectal tumor. Another common error of rectal palpation in women is to misjudge a vaginal tampon for a rectal wall lesion. With experience, however, there should be no confusion. A posteriorly displaced uterus may serve to warn the examiner that rigid proctosigmoidoscopy to the full length of the instrument may not be possible. Bidigital examination (i.e., one finger in the rectum and the other in the vagina) will readily distinguish any anatomic or pathologic variations.

The physician should then sweep the examining finger from anterior to posterior and back again,

consciously thinking of a possible lesion that could be present. The conscious thought process is emphasized because all too often this phase of the examination is performed reflexively, with the assumption that any lesion will be identified by the instrument if it is not perceived by the examining finger. However, a submucosal rectal nodule may not be visible and would otherwise go undiagnosed if direct visualization alone were employed. It may even be possible to feel a tumor in the sigmoid colon or a diverticular mass. Asking the patient to strain down (i.e., Valsalva’s maneuver—see Biography,

Chapter 7) will sometimes reveal a lesion in the upper rectum or rectosigmoid that otherwise would not be palpable. Examination above the prostate in the male patient or in the cul-de-sac in the female patient may reveal Blumer’s shelf,

a hard mass on the anterior rectal wall caused by metastatic tumor, usually of gastric or pancreatic origin. Attention to the presacral area may reveal an extrinsic mass (e.g., cyst, tumor, or sacrococcygeal chordoma). Finally, as the finger is withdrawn, the presence of anal disease is noted (e.g., hyper-trophied papilla, thrombosed hemorrhoid, stenosis, scarring).

Anoscopy

Anoscopy offers the best means to evaluate hemorrhoids, fissures, papillae, or other lesions of the anal canal. It is the requisite instrument if the physician is to perform an anal procedure or to treat a condition of the anal canal.

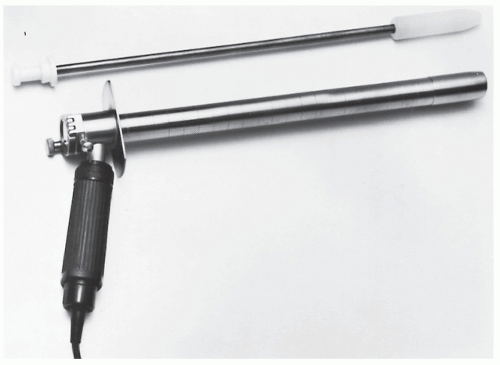

Numerous anoscopes and specula are available (

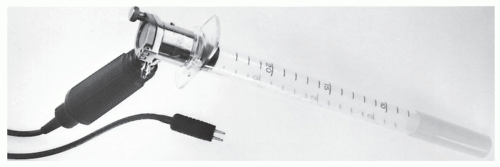

Figure 5-3). The physician can purchase either reusable or disposable fiberoptic anoscopes; some have a light source that fits into the instrument. Although relatively expensive, lighted anoscopes are ideal for diagnostic purposes. However, they may be somewhat limiting when a procedure is attempted through the instrument. Still, the choice of instrument and light source are variables that are decided based on an individual’s training, experience, and personal preference. A fiberoptic, malleable light source can also be used (

Figure 5-4), but a simple gooseneck lamp works reasonably well. When rotating the anoscope around the anal canal circumference, it is helpful to reinsert the obturator to turn the instrument. By doing so, the tendency to drag or pinch the anal canal or perianal skin is minimized.

Finally, when pathologic features are noted or treated, the site should be recorded as follows: right anterior, left lateral, and so forth. The use of o’clock descriptions should be abandoned because it requires a known patient position, and this may differ from one examination or examiner to another. Left posterior is left posterior even if the patient is hanging from a chandelier.

Rigid Proctosigmoidoscopy

The rigid sigmoidoscope is one of our most valuable diagnostic instruments available in the office setting. The examination is indicated to locate sources of bleeding, such as polyps and rectal cancer, and to evaluate proctitis. It may be used as part of the physical examination in asymptomatic

patients as an initial screening tool.

108 Investigators have confirmed a relatively high yield of asymptomatic polyps when proctosigmoidoscopy is performed as part of a complete physical examination. Swinton reported an incidence of 5% in a series of 3,000 routine examinations.

134 Majarakis and Portes noted almost an 8% incidence in 50,000 asymptomatic patients.

87 In addition, it is often used intraoperatively to assess the location of lesions and the integrity of a colorectal or coloanal anastomosis. While leak testing for a colorectal anastomosis may be performed without direct visualization, it is beneficial to view the anastomosis. Direct visualization allows the surgeon to assess whether there is a patent, intact, and hemostatic anastomosis at a time when a decision to revise it or to perform a fecal diversion may be made without inconvenience.

81,112As previously mentioned, the rigid sigmoidoscope is the optimal instrument for evaluation of the rectum. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are not as satisfactory as rigid sigmoidoscopy for evaluating ampullary lesions, unless a retroflexion maneuver is performed. Examination with the sigmoidoscope may reveal a mucosal excrescence, a polypoid lesion, cancer, inflammation, stricture, vascular malformation, or anatomic distortion from an extraluminal mass. It may also detect anal conditions, but it should not replace the anoscope for this purpose.

Preparation

A small-volume enema (e.g., Fleet) is advised prior to the procedure unless the patient has a history suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease. Vigorous catharsis the day before the examination and dietary restrictions are unnecessary.

Technique

There are five principles that should be adhered to if the physician is to conduct a safe, competent sigmoidoscopic examination:

Be expeditious.

Insufflate minimal air.

Always have a nurse or assistant available.

Keep talking to the patient: explain, reassure, distract.

Do no harm.

As mentioned earlier, a digital rectal examination should always precede instrumentation. In addition to providing valuable information, this procedure permits the sphincter to relax sufficiently to accept an instrument. The well-lubricated, warmed sigmoidoscope (if a reusable instrument is employed) is then inserted and passed to the maximal height as quickly as possible while causing minimal discomfort to the patient.

Air insufflation is of value in demonstrating the lumen of the bowel and is of even greater benefit in visualizing the mucosa when the instrument is withdrawn. Air insufflation

should, however, be kept to a minimum because it tends to cause abdominal cramping that may persist for many hours. The novice should not pass the sigmoidoscope without clearly observing the lumen. However, as skill develops, the physician can determine the amount of gentle pressure that can be safely exerted as long as the mucosa is seen to be sliding past. When an obstacle is reached, the instrument is withdrawn slightly and redirected to view the lumen again; it is then readvanced.

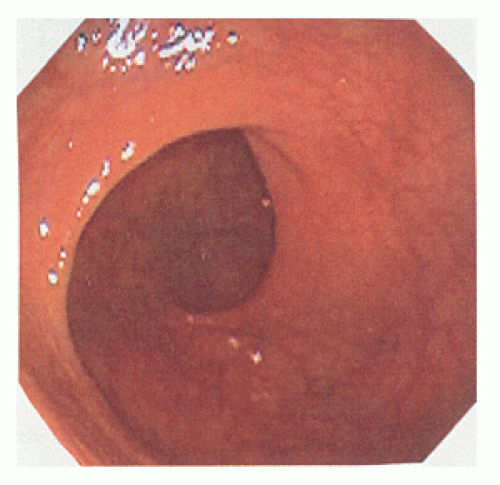

The physician should withdraw in a rotating fashion, carefully viewing the entire circumference of the bowel wall and ironing out mucosal folds to be certain that no small lesion is missed. Several lateral folds are often encountered in the rectum, the so-called valves of Houston (see Biography,

Chapter 1). Usually, three folds can be identified: the upper and lower are convex to the right, and the middle one is convex to the left (

Figure 5-9). The valves can serve as useful sites for performing rectal biopsy when the mucosa is grossly normal because of technical ease as well as the limited risk for perforation. Particular care should be taken to view the posterior wall that sits in the hollow of the sacrum. This may necessitate the awkward placement of the examiner’s head behind the patient’s knees (if the prone jackknife position is employed).

Successful insertion of the sigmoidoscope requires familiarity with the anatomy of the rectum and sigmoid colon. Knowing where the lumen probably is located without actually visualizing it permits the experienced examiner considerable freedom in passing the instrument. When the sigmoidoscope is inserted, the low rectal and mid-rectal areas are midline structures. As the upper rectum is reached, the bowel bends slightly to the left. At the rectosigmoid junction, the tendency is for the instrument to turn to the right and ventrally. Therefore, if difficulty is encountered at the level of 15 or 16 cm, a maneuver to the left may reveal the proximal bowel. At a level of 18 or 19 cm, a more vigorous manipulation to the right and ventrally may permit the proximal colon to be entered.

In a report from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, 25% of patients could not be examined beyond 20 cm.

119 Nivatvongs and Fryd reported the average depth of insertion to be 19.5 cm.

98 The two structures that may preclude complete examination (i.e., to 25 cm) are the uterus and the prostate gland. An enlarged prostate, a uterus containing fibroid tumors, or a uterus that is displaced posteriorly may make it impossible to pass the instrument beyond the 14- or 15-cm level. Persistence in attempting to achieve a higher penetration is usually unrewarding as well as potentially dangerous, and it is most uncomfortable for the patient. As mentioned previously, the potential for encountering this difficulty can often be predicted by careful digital examination.

Men are examined to the full length of the instrument much more often than women. Even when the uterus is surgically absent, fixation of the bowel in the pelvis may preclude further passage. A careful history will alert the examiner, thereby expediting the procedure and minimizing further discomfort.

Younger individuals are often more difficult to examine than older patients; because they usually have better sphincter tone, insertion of the instrument may cause more discomfort. The discomfort leads to apprehension and a tendency to bear down, making the examination more tedious. Also, pelvic organs are less lax in younger than in older women, causing it to be somewhat more difficult to displace the uterus and allow passage of the sigmoidoscope.

Procedures Performed through the Sigmoidoscope

Three procedures are frequently performed through the rigid proctosigmoidoscope:

Biopsy

Electrocoagulation

Snare excision

Gear and Dobbins have published a comprehensive review of the diagnostic usefulness of rectal biopsy, to which is appended an extensive bibliography.

39 It is interesting to note, however, the virtual absence of writings on rigid sigmoidoscopic procedures since the 1980s, owing to the fact that the technique has been essentially replaced by the flexible instruments. This is unfortunate because many diagnostic procedures are preferably performed through the rigid sigmoidoscope, not to mention measurement of the level of lesions that have been identified.

Instruments and Methods

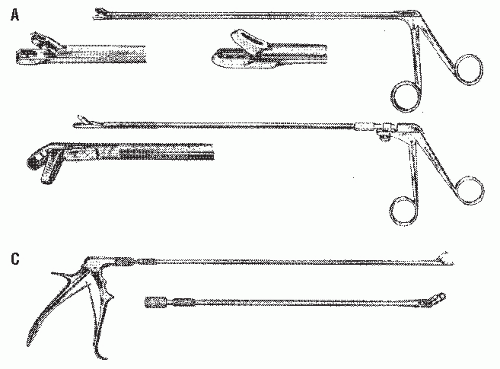

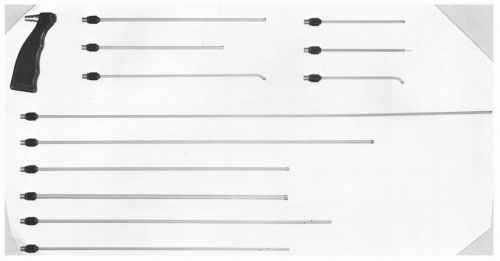

Biopsy forceps are available with various biting tips (

Figures 5-10 and

5-11). Some instruments are electrified

for biopsy and coagulation, but this is usually not necessary as bleeding is rarely a problem when a biopsy is taken from an obvious lesion (see Complications of Procedures). Biopsy of the mucosa when a lesion is not present, such as is undertaken for amyloid, should always be performed on the posterior wall or on a valve of Houston. The valves are only mucosal structures, so perforation is virtually impossible. Conversely, biopsy of this area is not advisable if the physician wishes to obtain a sample of muscularis propria.

Electrocoagulation obviously requires familiarity with electrosurgical equipment (

Figures 5-12 and

5-13). Most surgeons find the instrument setting that works well for the procedure performed, but the same maneuvers carried out in the hospital, with similar or different equipment, may produce inadequate or too vigorous electrocoagulation. The physician is advised to test any unfamiliar equipment on a bar of soap, adjusting the setting for the appropriate conditions. Although it is helpful to know that a small lesion is a neoplasm (e.g., polypoid adenoma rather than a hyperplastic polyp), biopsy of every mucosal excrescence is meddlesome and unnecessary. The physician can feel content to fulgurate lesions smaller than 5 mm without biopsy. However, for larger tumors, it is preferable for one to obtain pathologic confirmation through either a biopsy or a snare excision.

Use of the

wire loop snare (

Figure 5-14) requires considerably more skill than fulguration alone. The technique usually permits complete excision with one application, although sometimes multiple snarings are required to remove larger growths. This is still can be an office procedure if the surgeon has the appropriate equipment.

The snare is passed around the polyp and the wire loop slowly closed; the instrument is jiggled as the wire tightens the base. This maneuver permits adjacent mucosa to escape and minimizes the risk of burning the bowel wall. Coagulation rather than cutting current is preferred for snare excision because greater control of the speed of cutting through tissue can be exerted. If a thick pedicle is present, the physician may take several minutes to excise the specimen. After the polyp is removed, it is helpful to have long alligator or biopsy forceps to retrieve it.

Principles of Electrosurgery

It is useful, especially for the resident who may not be familiar with electrosurgical equipment, to pen a few words about electrosurgical principles. The reader is encouraged to read a monograph on this subject that has been made available to members of the profession by Valleylab, a division of Covidien (Norwalk, CT). The following glossary (

Table 5-2) of definitions and principles is useful.

Complications of Procedures Bleeding

Bleeding is an unusual concern indeed if a biopsy is taken from a lesion, benign or malignant. The occasional incident

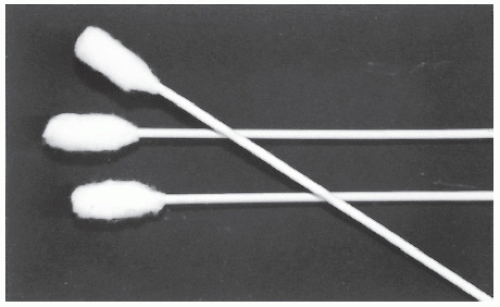

of bleeding usually occurs when a specimen is obtained from a normal-appearing rectum, that is, when the physician is seeking a diagnosis of conditions such as Hirschsprung’s disease or amyloidosis. Unless the bleeding is pulsatile, it is unnecessary to prolong the examination to await complete hemostasis. If persistent bleeding occurs, it may be treated by applying direct pressure with an epinephrine-soaked, cotton-tipped stick (i.e., a chimney sweep) or by saturation with the styptic, Monsel’s solution, rather than by electrocoagulation. Electrocoagulating a bleeding area when a biopsy specimen has been taken from a grossly normal rectum may lead to perforation.

36If bleeding occurs from the pedicle of a snared polyp, it may be secured by fulguration, by application of pressure with an epinephrine-soaked chimney sweep, by the use of a long-armed (i.e., extended) rubber ring ligator, or by an endoscopic clip.

Explosion

In contrast to closed-system flexible endoscopy, electrocoagulation or snare excision with the open-ended sigmoidoscope does not require a full bowel preparation. Under these circumstances, an explosive gas mixture may be present. However, there are no adverse consequences because venting is sufficient to prevent proximal bowel injury. Although the “popping sound” or “firecracker-sounding explosion” may be quite disconcerting, no harm will ensue, at least to the patient.

Perforation

Bowel perforation from a biopsy, with or without electrocoagulation, or snare excision is a potential hazard that can lead to perforation. However, this is extremely uncommon for two reasons. First, the surgeon limits biopsy of grossly normal bowel to the area below the peritoneal reflection. Even a transmural injury at this location is generally harmless. Second, colonoscopy has supplanted polypectomy through the rigid sigmoidoscope. When a lesion is found within range of the short instrument, the patient is inevitably and appropriately submitted to complete colon evaluation.

As with colonoscopy perforation, the patient may develop signs and symptoms of bowel perforation within a few minutes of electrocoagulation, polyp excision, or biopsy, or septic problems may develop as long as 10 days later. Anyone complaining of abdominal pain who has undergone such a procedure within that interval requires reevaluation and examination. The presence of free intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal gas establishes the diagnosis of a perforated viscus, but in the absence of obvious peritonitis, treatment may consist of in-hospital observation, restriction of oral intake, intravenous fluid replacement, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Fever or leukocytosis is not necessarily an indication for surgical intervention. Each clinical situation must be addressed individually. In an equivocal circumstance, the physician may consider a water-soluble enema study (i.e., Gastrografin enema). However, no one should be critical of the surgeon who performs a negative exploratory laparotomy for an individual whose abdominal signs and symptoms are increasing in severity or who continues to manifest fever and leukocytosis. If patients are going to improve on conservative treatment, they almost always will do so within 24 hours. The principles of management are similar to those described for perforation following colonoscopy (see

Chapter 6).