Equipment

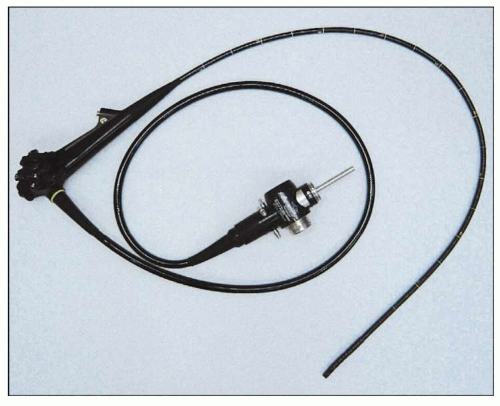

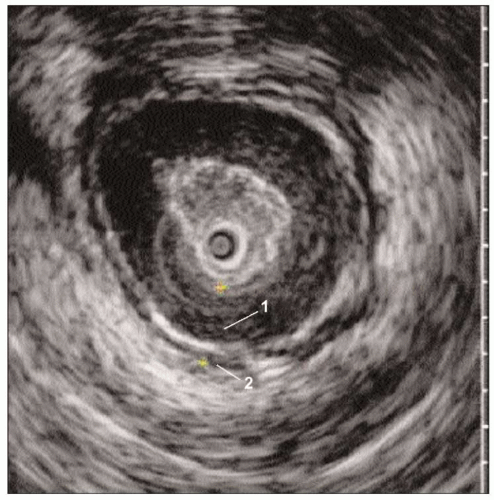

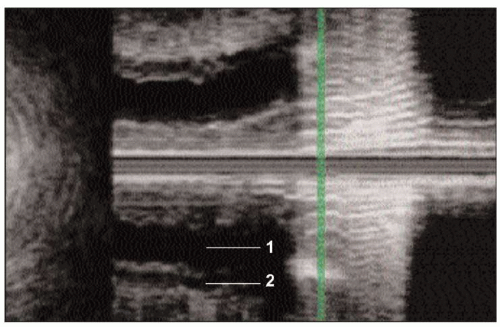

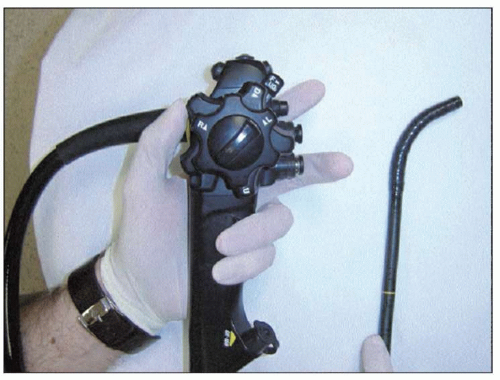

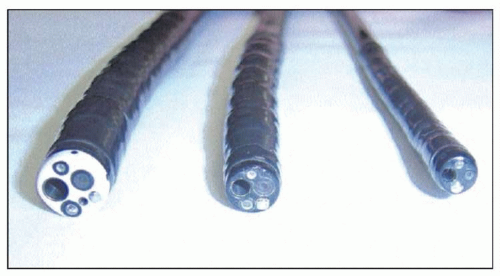

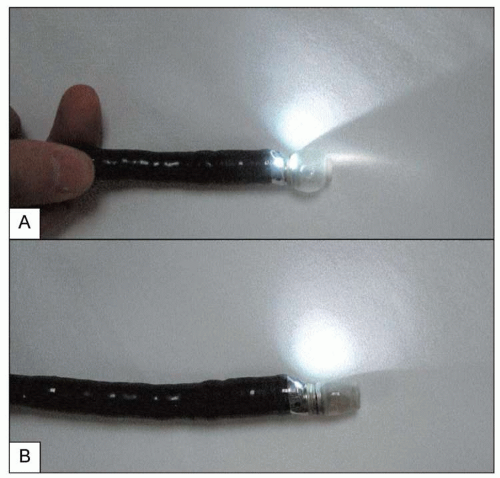

Endoscopy allows direct visualization of the esophageal mucosa and detect structural abnormalities. Endoscopes use fiberoptic technology to capture and transmit the image from the distal end of the endoscope (

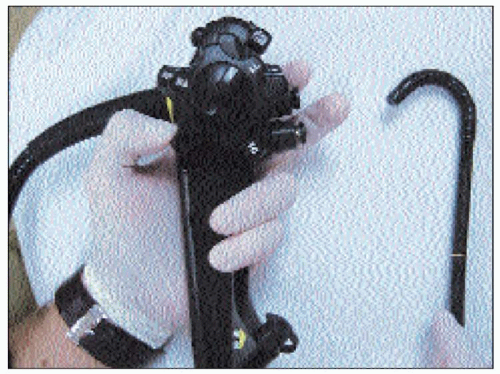

2.1). Four-way tip deflection is permitted by the use of two control knobs, one with up/down movement and the other with right/left movement (

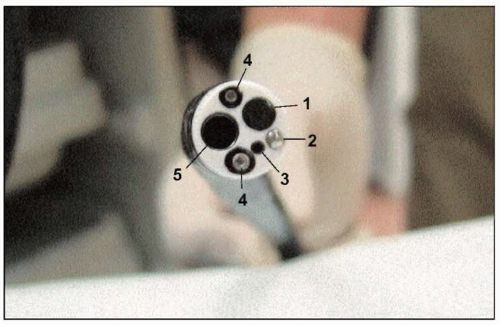

2.2, 2.3 and 2.4). Endoscopes are equipped with internal channels for air, water, suction, and instruments (

2.5, 2.6). The separate instrument channel allows the passage of biopsy forceps and other instruments used for treatment of upper

GI disorders. Visualization is improved when air is used to insufflate the esophagus and stomach, which are normally compressed.

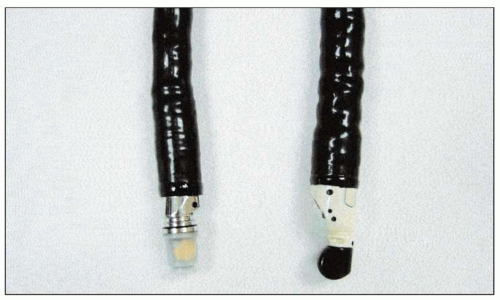

Both small and large scopes are available (

2.7, 2.8): the ‘therapeutic’ endoscope contains a larger instrument channel that permits passage of ‘jumbo’ biopsy forceps and larger coagulation devices, whereas ‘pediatric’ endoscopes may be as small as 4 mm and allow transnasal or transoral endoscopy without sedation.

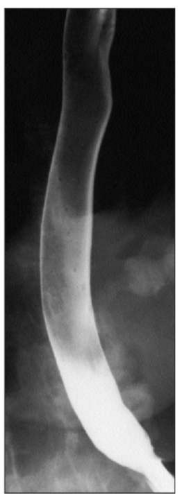

Technique

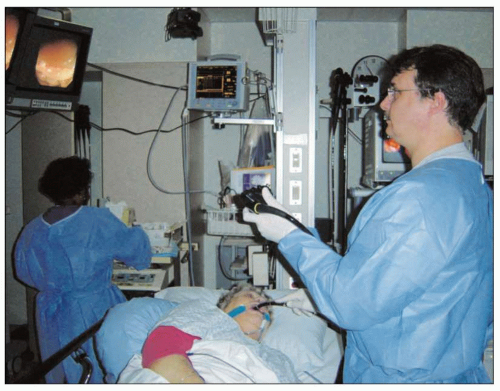

In the United States, upper

GI endoscopy is routinely performed under conscious sedation. Local anesthetic is sprayed on the posterior pharynx and intravenous sedation administered while the patient is in the left lateral decubitus position (

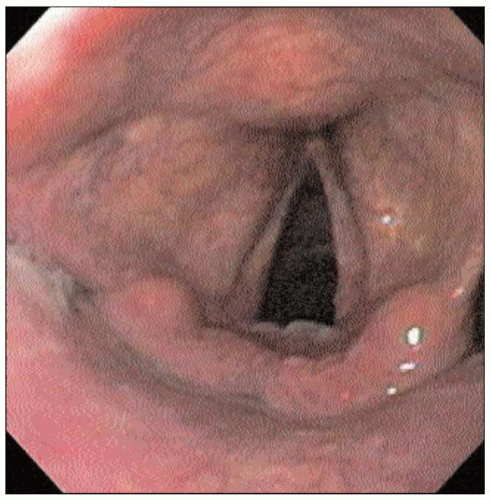

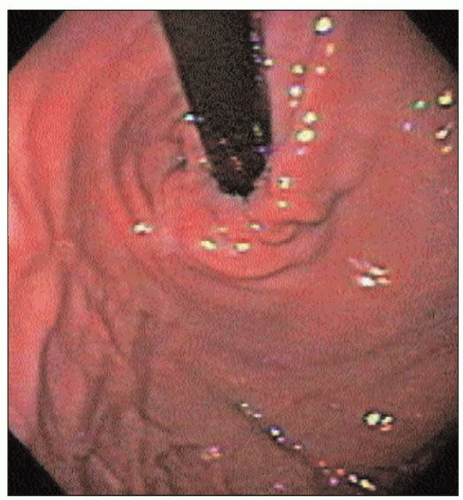

2.9). The endoscope is inserted into the posterior pharynx where the pharynx and larynx can be examined for abnormalities (

2.10). The endoscope is then advanced under direct vision into the tonically closed upper esophageal sphincter. The patient is asked to swallow to relax the upper esophageal sphincter (

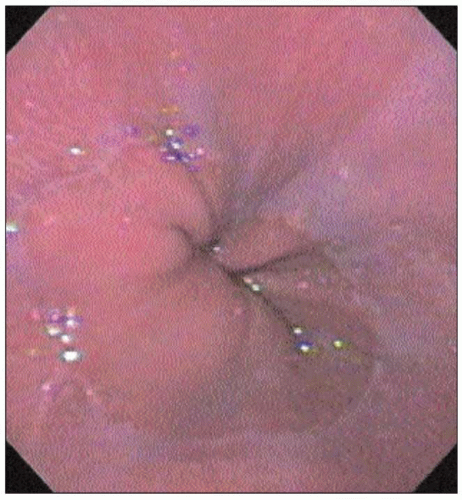

UES) and the endoscope is advanced to the proximal esophagus, where the mucosa should normally be smooth and light pink (

2.11, 2.12).

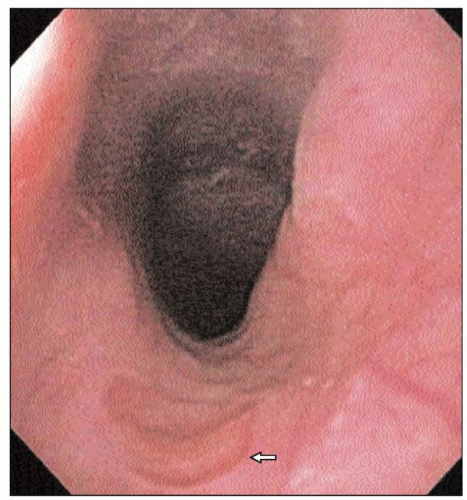

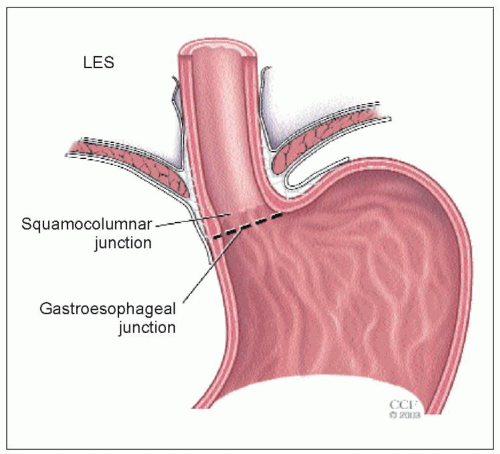

The area of the gastroesophageal junction (

GEJ) is carefully examined to identify specific landmarks (

2.13), and is defined by the proximal margin of the gastric folds. The squamocolumnar junction (

SCJ) can be recognized by the irregular Z-line demarcating the interface between the light pink esophageal squamous mucosa and the red columnar mucosa gastric mucosa (

2.14).

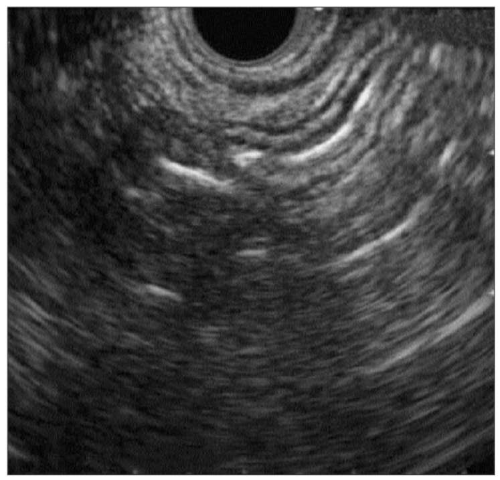

The diaphragmatic hiatus can be identified by diaphragmatic contraction noted during patient respiration. The

SCJ, the

GEJ, and the diaphragmatic hiatus are normally located at the same level, unless pathology is present. In patients with Barrett’s esophagus, the

SCJ is more proximal in the esophagus than the

GEJ, whereas in patients with hiatal hernia, the

GEJ is more proximal than the diaphragmatic indentation. While in the stomach, the endoscope is ‘retroflexed’ to look back at the

GEJ; this yields a better view of the gastric side of the junction (

2.15).