1 Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Social Impact of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Introduction

POP is defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as the descent of one or more of the following structures: the anterior or posterior vaginal wall, the apex of the vagina, or the vault. Loss of the vaginal support is observed in 43% to 76% of patients during routine gynecologic care and in up to 3% to 6% with a descent beyond the hymen. (Swift et al, 2005; Samuelsson et al, 1999)

Prevalence and Incidence of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

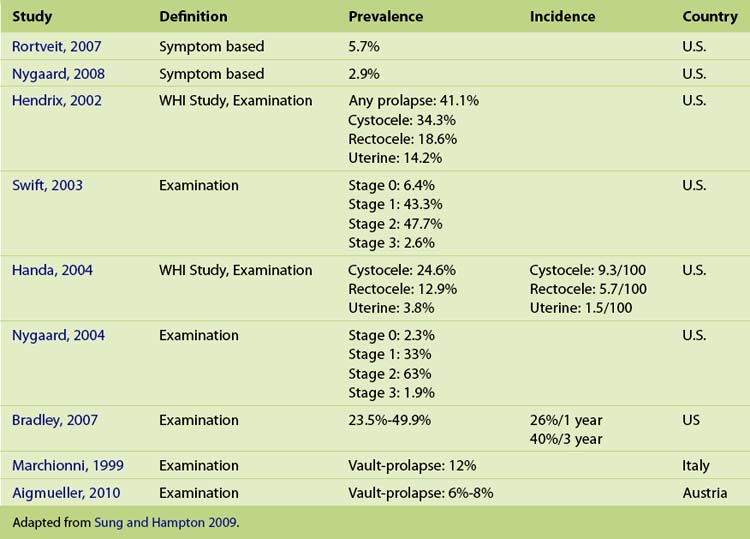

Epidemiologic studies of the natural history, incidence, and prevalence of POP are currently lacking. It is widely accepted that 50% of women will develop prolapse, but only 10% to 20% of those will seek evaluation for their condition. (Phillips et al, 2006) In the current literature, the overall prevalence of POP shows significant variation, depending on the definition used, ranging from 3% to 50% (Table 1-1). When POP is defined and graded on symptoms, the prevalence is 3% to 6%, as compared with 41% to 50% when based on examination, indicating that the majority of women with prolapse are asymptomatic. (Phillips et al, 2006; Samuelsson et al, 1999; Nygaard et al, 2008; Swift, Tate, Nicholas, 2003) On examination, anterior compartment prolapse is the most frequently reported site of prolapse, is detected twice as often as posterior compartment defects, and three times more often than apical prolapse. (Hendrix et al, 2002; Handa et al, 2004) After hysterectomy, 6% to 12% of women will develop vault prolapse (Marchionni et al, 1999; Aigmueller et al, 2010), and in two thirds of these cases, multiple compartment prolapse is present. (Morley, DeLancey, 1988)

Little knowledge of the natural history of POP is available. The reported incidence for cystocele is approximately 9 per 100 women-years, 6 per 100 women-years for rectocele, and 1.5 per 100 women-years for uterine prolapse. (Handa et al, 2004) Bradley et al, report the 1-year incidence of POP at 26% and the 3-year incidence at 40% with regression rates of 21% and 19%, respectively. In general, older parous women are more likely to develop new or progressive POP than to show regression. Of the women over 65 years of age, 10% have had prolapse progression of more than 2 cm, whereas only 2.7% of women younger than 65 years had a regression by the same amount. (Bradley et al, 2007)

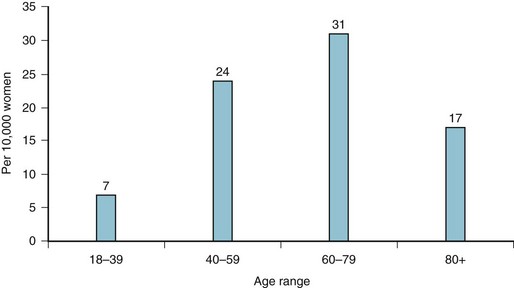

In a large demographic study, Luber and associates (2001) have shown that the peak incidence of symptoms attributed to prolapse is between the ages of 70 and 79 years, whereas POP symptoms are still relatively common in women of younger age (Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1 Distribution of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) among women seeking care in the United States (2000).

Demographic changes with an aging population have significant implications for the future planning of women’s health services. Wu and colleagues (2009) have predicted that by 2050 the number of women suffering from symptomatic POP in the United States will increase at minimum by 46% (from 3.3 to 4.9 million women) and, in a “worst-case scenario,” up to 200% or 9.2 million women with POP.

Incidence and Prevalence of Prolapse Surgery

Both incidence and prevalence for prolapse surgery increase with age. Women older than 80 years of age are currently the fastest growing segment of the population. The estimated lifetime risk of an American woman undergoing at least one surgical intervention by the age of 80 years is 6.3% with 30% requiring subsequent surgeries. (Olsen et al, 1997) However, a more recent prospective study showed a significantly lower subsequent surgical rate of only 13%, which may be explained by improved surgical procedures. (Clark et al, 2003) The longevity or durability of POP surgery is an important variable for planning and thus requires ongoing evaluation.

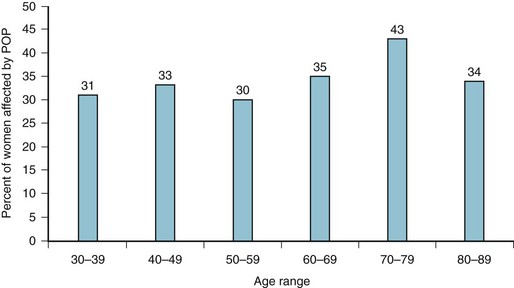

The annual incidence for POP surgery is reported to be between 1.5 (Boyles, 2003) and 1.8 (Shah et al, 2007) cases per 1000 women-years with the incidence peaking in women between the ages of 60 and 69 years. Shah and associates (2007) also demonstrated a peak incidence in 70-year-old women. However, Luber and colleagues (2001) reported surprisingly high numbers of younger women who were also undergoing surgical treatments with a similarity in the prolapse symptoms (Figure 1-2). A more recent study by Smith and associates (2010) reported a lifetime risk of undergoing prolapse surgery as high as 19% in Western Australia. This figure is three times higher than the 6.3% lifetime risk for POP surgery reported by Olsen and others (1997) and requires further evaluation of local factors, as well as other definitions that may have contributed.

In the United States, POP is thought to be the leading cause for more than 300,000 surgical procedures per year (22.7 per 10,000 women) with 25% undergoing subsequent surgical procedures at a total annual cost of more than 1 billion dollars. (Brown et al, 2002; Boyles, Weber, Meyn, 2003; Silva et al, 2006; Shah et al, 2007) Also of note is a study during a 9-year period (1996 to 2005) that reported an increase of 40% of the ambulatory costs related to pelvic floor disorders; if these figures are extrapolated to POP surgery costs, the total annual cost would be over 1.4 billion dollars.

The incidence of prolapse requiring surgical correction after a hysterectomy is 3.6 per 1000 women-years, according to a large cohort study conducted by Mant and colleagues (1997) in the United Kingdom. The cumulative risk rises to 5% 15 years after hysterectomy.

Etiologic Features and Risk Factors of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

The etiologic features of POP are still poorly understood and multifactorial, attributable to a combination of risk factors and varying from patient to patient. (Schaffer, 2005) A reduction of the stability of the pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue through tearing, trauma, and chronically raised intraabdominal pressure are likely to be the key mechanisms involved in the development of POP (Table 1-2).

Table 1-2 Risk Factors for the Development of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

| Factors | Impact on the Development Pelvic Organ Prolapse |

|---|---|

| Vaginal delivery, parity | RR two children: 8.4* |

| RR four children: 10.9* | |

| 10%-20% every additional child | |

| Strong family history | Mother: OR 3.2 (95% CI 1.1-7.6) |

| Sister: OR 2.4 (95% CI 1.0-5.6) | |

| Advancing age | 60-69 years of age: OR 1.2 (95% CI 1.0-1.3) |

| 70-79 years of age: OR 1.4 (95% CI 1.2-1.6) | |

| Connective tissue disorder | Marfan syndrome: 33% |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: 75% | |

| Hernias: 31% | |

| Overweight | 2.51 (95% CI 1.18-5.35) |

| Obesity | 2.56 (95% CI 1.23-5.33) |

| Chronic increase of intraabdominal pressure | Physical work: OR 2.0 (95% CI 1.1-3.6) |

| Previous gynecologic surgery | Posthysterectomy POP: 6%-12% |

| Postcolposuspension: 30% risk for rectocele or apex descent | |

| Racial differences | Caucasian: 5.35 (95% CI 1.89-15.12) for POP |

| Hispanics: 4.89 (95% CI 1.64-14.58) for POP |

CI, Confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; POP, pelvic organ prolapse; RR, relative risk.

* As compared to nulliparous women.

Vaginal birth, advancing age, and an increased body mass index (BMI) or obesity are known to be the most consistent risk factors of developing uterogenital prolapse; however, numerous other factors contribute to this condition. The incidence of POP is largely correlated to vaginal birth, which is well documented in epidemiologic and cohort studies. (Nygaard et al, 2008; Rortveit et al, 2007) Vaginal delivery leads to tearing, stretching, and the dislocation of the pelvic muscles and nerves. In the Oxford Family Planning Study, increasing vaginal parity was the most relevant and strongest risk factor for POP in women younger than 60 years of age. Women who had two or four children delivered vaginally had a relative risk (RR) of developing a POP of 8.4 and 10.9, respectively, as compared with nulliparous women. Hendrix and associates (2002) showed similar findings, reporting that each additional childbirth increases the risk of developing POP by 10% to 20%. Forceps delivery, high infant birth weight, prolonged second stage, and young age (under 25 years old) at the first pregnancy are considered additional obstetric risk factors for POP but less than vaginal childbirth and parity. (Swift, Tate, Nicholas, 2003; Moalli et al, 2003)

Elective Cesarean section reduces the incidence of POP. Women who have undergone vaginal delivery have a higher risk of developing prolapse symptoms as compared to those who had elective cesarian section ( RR 1.82 95% CI 1.04 to 3.19). These data estimate that for every seven women with elective cesarean section, one woman would be prevented from developing a pelvic organ disorder. (Lukacz et al, 2006) With the steadily increasing number of elective cesarean sections, and thus the decreasing numbers of vaginal deliveries, a reduction in the incidence of POP may be achieved in the future.

Advancing age is strongly associated with POP. Both prevalence and the incidence significantly increase with age. Progressing denervation of the pelvic floor muscles with age may contribute to POP. (Wall, 1993) The relative prevalence of POP rises approximately 40% with every decade of life. (Swift et al, 2005) The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) stated that the risk for developing POP in women between ages 60 and 69 years and between ages 70 and 79 years (odds ratio [OR] 1.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.3 and OR 1.4; 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6 respectively) is higher than women aged 50 to 59 years of age.

Obesity and conditions of chronically increased intraabdominal pressure, such as constipation, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and regular weightlifting, place excessive strain on the pelvic floor, supporting muscles, connective tissues, and pudendal nerves. (Swift, Tate, Nicholas, 2003; Spence-Jones et al, 1994) As a result, women who are overweight or obese are at high risk of developing POP with an OR of 2.51 (95% CI 1.18 to 5.35) and 2.56 (95% CI 1.23 to 5.35), respectively. Similarly, overweight women (BMI greater than 26 kg/m2) are more than 1.5 to 5.9 times more likely to undergo prolapse surgery than those with normal BMI. (Moalli et al, 2003; Swift, Tate, Nicholas, 2003; Hendrix et al, 2002) The obesity epidemic in developed countries will further challenge POP surgeons in the future.

Other conditions with chronically increased intraabdominal pressure, such as chronic constipation or straining to defecate as a young adult, are highly associated with the development of prolapse when compared with women with normal bowel function (61% versus 4%). Many women who have physically demanding jobs such as nurses, cleaners, or caregivers are twice as likely to develop POP, as compared with sedentary women. (Miedel et al, 2009) These women have a high chance of undergoing a surgical procedure for POP.

Quantitative and qualitative differences in collagen are likely to contribute to POP. Some histopathologic studies have showed that women with POP have proportionally more type III collagen than other subtypes. (Moalli et al, 2005) Jackson and associates (1996) found in premenopausal women with POP a reduction of total collagen and secondary increased collagenolytic activity in samples of vaginal tissue, as compared with those without prolapse. Differences in collagen structure may possibly account for the strong familial links to prolapse development. Women with a first-degree family history for this condition have a much higher risk for developing POP with a mother OR 3.2 (95% CI 1.1 to 7.6) or a sister OR 2.4 (95% CL 1.0 to 5.6) reporting prolapse. (Brown et al, 2002; Chiaffarino et al, 1999)

POP and hernias share similar pathophysiologic features. Patients with hernias show a decreased collagen synthesis metabolism, a protease-antiprotease imbalance with increased matrix metalloproteinases activity, and a reduced collagen type I/III ratio. Segev and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that women with POP have a significantly higher total prevalence of hernias (31.6% versus 5%, p = 0.0002), compared with women with mild or no prolapse.

In terms of racial or ethnical differences, studies have shown that African-American women have a lower prevalence of POP than Caucasian-American women (Luber, Boero, Choe, 2001; Shah et al, 2007; Whitcombe et al, 2009) with a prevalence ratio of 5.35 (95% CI 1.89 to 15.12) and 4.89 (95% CI 1.64 to 14.58) for symptomatic prolapse in Caucasian and Latina women, respectively. This prevalence may be the result of a smaller pelvic outlet, compared with women from European descent.

Connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome with an impaired collagen and elastin synthesis and metabolism, have a higher rate of POP. In a small cohort study, 33% of women with Marfan syndrome and 75% with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome developed POP. These findings underline the hypothesis that connective tissue disorders play an important role in the cause of POP. (Carley, Schaffer, 2000)

Prior pelvic surgery may also be a risk factor for subsequential POP surgery, depending on the indications. Approximately 7% of women who have undergone a previous hysterectomy are considered at risk for subsequential POP. (Moalli et al, 2003; Mant, Painter, Vessey, 1997) The risk of developing recurrent or nontreated compartmental prolapse is 5.5 times higher in women whose primary indication for hysterectomy was prolapse. Similarly, Dällenbach and others (2007) showed that the risk of subsequential prolapse surgery was 4.7 times higher in women whose initial hysterectomy was for prolapse and 8.0 times higher if preoperative prolapse stage II or more was present.

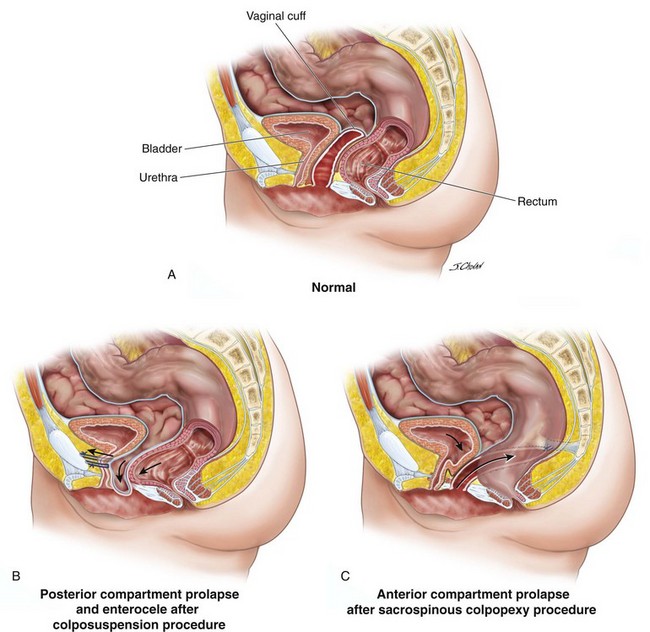

Prior pelvic surgery or iatrogenic prolapse is well reported with anterior compartmental prolapse observed in up to one third of women after sacrospinous colpopexy; in addition, posterior compartmental defects increased by one third in those who undergo colposuspension as compared to suburethral tape continence surgery (Figure 1-3). (Ward, Hilton, UK and Ireland TVT Trial Group, 2008) More recently, a single study found that de novo POP greater than the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system stage II occurred in 46% after an isolated anterior vaginal mesh repair and 25% after an isolated posterior vaginal mesh repair. These prevalence rates are of great concern, and further evaluation of the use of mesh in prolapse surgery is urgently indicated. (Withagen, Vierhout, Milani, 2010)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree