Obese patients present many unique challenges to the endoscopist. Special consideration should be given to these patients, and endoscopists need to be aware of the additional challenges that may be present while performing endoscopic procedures on obese patients. This article reviews the special risks that obese patients face while undergoing endoscopy, endoscopic management of patients postbariatric surgery, and future role of endoscopy in the management of obese patients.

Obese patients present many unique challenges to the endoscopist. Special consideration should be given to these patients, and endoscopists need to be aware of the additional challenges that may be present while performing endoscopic procedures on obese patients. This article reviews the special risks that obese patients face while undergoing endoscopy, endoscopic management of patients postbariatric surgery, and future role of endoscopy in the management of obese patients.

Endoscopy in obese patients: unique challenges

Upper Endoscopy in Obese Patients

As with all patients, it is important to ensure that an appropriate indication exists before performing endoscopy in obese patients. Obese patients are more likely than normal controls to have upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, and hiatal hernias and gastritis are more likely identified by upper endoscopy. It has also been shown that an elevated body mass index (BMI) is associated with an increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and possibly gastric cardia. In addition to increased risk for GI symptoms, obese patients also have an increased risk for underlying GI pathology. Therefore, there may be a lower threshold for performing endoscopy in obese patients despite the increased risk of the procedure related to their obesity.

Upper endoscopy is commonly recommended before performing bariatric surgery. This is partly because of the fact that there is an increased prevalence of upper GI pathology in obese patients and that, depending on the bariatric surgery performed, the postsurgical anatomy may make future visualization of portions of the upper GI tract difficult, if not impossible. Furthermore, the endoscopic findings such as a large hiatal hernia, erosive esophagitis, or ulcer may alter the specific type of bariatric surgical procedure performed. As an example of the increase in associated pathology in obese patients, 1 study demonstrated that 42% of the subjects who underwent upper endoscopy before performing bariatric surgery required preoperative therapy for the pathology identified on their preoperative upper endoscopy. However, this finding is not consistently found in the literature because another study demonstrated that routine upper endoscopy on subjects before bariatric surgery resulted in a change in the planned operative procedure in only 4.9% of cases.

The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has recently published guidelines regarding the use of endoscopy in patients before undergoing bariatric surgery. The recommendations in those guidelines are tailored to the bariatric procedure that is to be performed. They recommend the following:

- (1)

All patients with upper GI symptoms who are to undergo bariatric surgery should undergo a preoperative upper endoscopy.

- (2)

Upper endoscopy should be considered in all subjects who are to undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), regardless of the presence of symptoms.

- (3)

Preoperative upper endoscopy should be considered in asymptomatic patients before performing gastric banding to exclude large hiatal hernias because this may alter the surgical approach.

The authors concur with these recommendations and emphasize that if routine screening upper endoscopy is not performed before bariatric surgery, the endoscopist will have a low threshold for performing upper endoscopy for symptom evaluation in prebariatric surgery patients.

Colonoscopy in Obese Patients

A case-control study has demonstrated a hazard ratio of 3.72 for the development of colon cancer in subjects with a BMI of more than 28, and a prospective study revealed the rate ratio for colon cancer mortality in men with a BMI of more than 32.5 to be 1.9 and for women with a BMI of more than 32.5 to be 1.26. Despite this increased risk of colon cancer prevalence and mortality in obese subjects, performing colonoscopy on patients with a high BMI can be challenging. It has been shown that obese patients are more likely to have an inadequate bowel preparation, and the use of a more aggressive bowel preparation in obese subjects has been suggested. There has been a speculation that cecal intubation may be more difficult in obese patients (eg, difficulty in achieving adequate external pressure, repositioning of the patient); however, this does not appear to be the case because recent studies have actually shown cecal intubation to be more difficult in subjects with a lower BMI. The authors have, however, found that the use of the longer enteroscope may help attain cecal intubation when there is difficulty intubating the cecum, which occurs as a result of looping or other factors during colonoscopy in obese patients. In addition, placing the obese patient in a prone position may improve cecal intubation time and reduce patient discomfort.

Sedation Issues in Obese Patients

When an endoscopic procedure is indicated in an obese patient, there are several additional considerations that should be taken into account. One additional assessment of airway risk, although well accepted for anesthesia evaluation but not universally used in endoscopy, is the Mallampati score. This score was originally devised to stratify risk related to endotracheal intubation, but it is also correlated with the risk of sleep apnea. The obese patient at risk for sleep apnea may also present an additional airway risk during endoscopy. Thus, the authors suggest that the endoscopist be aware of the possible utility of this scoring system in assessing the obese patient’s risk for endoscopic sedation. It is also likely that the positioning of the patient further affects airway compromise in the obese patient more than it does in the nonobese. As such, performing the procedure with the patient in supine position may present greater airway risk in obese than in nonobese subjects.

It is also well established that obese patients are at an increased risk for sleep apnea, and patients with sleep apnea are at an increased risk for developing cardiovascular complications related to the use of sedation. The authors completed a study of 397 subjects who underwent average-risk endoscopy at their institution and found that 35% had a BMI of more than 30, and 82% of those subjects were identified, by means of a validated sleep apnea questionnaire, as having high risk for sleep apnea. The study further revealed that subjects who were identified as having high risk for sleep apnea were more likely to have oxygen desaturation and hypercapnic episodes when undergoing sedation for standard, low-risk endoscopy. Based on these observations, it was concluded that when a patient presents for endoscopy and sleep apnea is either suspected or confirmed, the endoscopist should use additional caution with the delivering and monitoring of sedation for endoscopy. Capnography may prove to be a helpful tool for monitoring these higher risk patients.

Endoscopy in obese patients: the postbariatric surgery patient

Postbariatric Surgery Symptoms: When to Do Endoscopy?

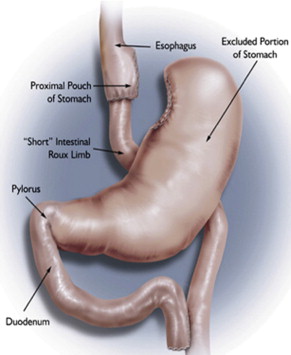

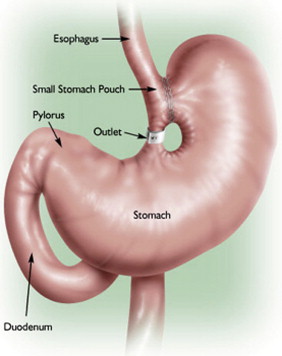

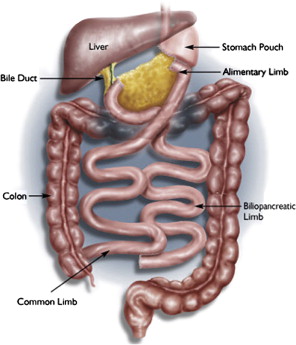

Currently, the most common bariatric surgical procedures performed are the RYGB ( Fig. 1 ) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) ( Fig. 2 ). Other less commonly used procedures exist, such as vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) ( Fig. 3 ), sleeve gastrectomy ( Fig. 4 ), and biliopancreatic diversion ( Fig. 5 ). The variation and extent of bariatric surgical procedures as well as marked differences in anatomy and complications associated with the various procedures mandate that endoscopists familiarize themselves with the surgical anatomy and complications before performing the procedure. Often it is helpful to speak directly with the surgeon who performed the procedure to clarify exactly what was done and the anatomic result of the surgical procedure. If contact cannot be made, a detailed review of available surgical reports is warranted.

Upper GI symptoms are frequently seen in postbariatric surgery patients. The most common symptoms encountered are heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, persistent weight loss, and failure to lose weight or a plateau in weight loss that is less than expected. The incidence of new reflux symptoms after bariatric surgery has not been well studied, and although there are some who believe that lap band surgery can worsen preoperative reflux, the preponderance of the literature suggests that gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms are likely to improve after a bariatric surgical procedure is performed.

Nausea, vomiting, or continued weight loss is often because of dietary noncompliance, such as rapid or large-volume food ingestion or inadequate chewing of ingested food, or the development of an anastomotic stricture. An early plateau in weight loss may also be because of dietary indiscretion or the development of anastomotic excessive dilation. Upper endoscopy should be considered (1) if upper GI symptoms are severe or persistent despite the patient eating an appropriate postsurgical diet, (2) if the patient begins to not tolerate a diet that had previously been tolerated at one point in the postoperative period, or (3) if weight loss is less than anticipated.

A prospective study of 1079 subjects who underwent RYGB revealed that significant pathology was identified in 68.4% of symptomatic patients referred for upper endoscopy. The most common pathology identified was anastomotic stricture (52.6%), followed by marginal ulcer (15.8%), unraveled nonabsorbable sutures leading to functional obstruction (4%), and gastrogastric fistula (2.6%). Abnormal findings were seen in 85% of patients with dysphagia, 65% with nausea and/or vomiting, and 42% with abdominal pain. This study also noted that post-RYGB patients with an abnormal upper endoscopy had symptom onset at a mean of 110.7 days postprocedure compared with 347.5 days for patients with a normal upper endoscopy. In cases where a leak or fistula is suspected, one should start by getting an upper GI series, and if an abscess or seroma is suspected, a computed tomographic (CT) scan should be obtained before proceeding with endoscopy.

Management of Postbariatric Surgery Complications: Stenosis

The most common site of stenosis after bariatric surgery occurs at the gastrojejunal anastomosis after RYGB; however, other areas of stenosis have been described, including at the gastric band, area of passage through the mesocolon, jejunojejunal anastomosis, and at the site of adhesions. Studies have suggested that gastrojejunal anastomotic strictures occur in 5.1% to 6.8% of cases after RYGB, and most occur within the first year after surgery. Endoscopic management of anastomotic strictures can be accomplished with through-the-scope balloon dilation or with Savary-Gilliard dilators (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA). An approach for the management of post-Roux-en-Y strictures has been proposed that takes into account the severity of the initial stenosis. This approach recommends (1) mild stenosis (able to pass 10.5-mm endoscope) be dilated to 16 to 18 mm with pneumatic dilation, (2) moderate stenosis (able to pass 8.5 mm endoscope) be managed with an initial pneumatic dilation up to 15 mm, followed 2 weeks later by dilation with Savary-Gilliard dilators up to 15 to 18 mm, and (3) severe stenosis (able to be traversed only with a wire guide) be dilated initially with a 6-mm balloon over a guidewire, with a maximum initial dilation not to exceed 10 mm, and subsequent dilations up to 15 mm with a Savary-Gilliard dilator depending on the success of previous dilations.

There is some concern that dilation of strictures at the anastomosis can result in weight gain because of loss of the restrictive effect of the anastomosis; however, it has been shown that dilation of more than 15 mm does not appear to result in weight gain and most patients can have anastomotic narrowing managed with as few as 1 to 2 dilations. When standard dilation is ineffective, additional strategies include cutting and removing exposed suture when present, injection of the anastomosis with saline or steroids postdilation, or even use of needle knife to disrupt scar tissue at the anastomosis site.

Management of Postbariatric Surgery Complications: Marginal Ulceration

Marginal or stomal ulceration occurs at the gastrojejunal anastomosis site, most frequently on the intestinal side of the anastomosis. Several predisposing factors have been proposed, including ischemia, use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, staple line disruption, suture or staple erosion, gastrogastric fistula, and presence of Helicobacter pylori . Presence of H pylori preoperatively, even when adequately treated before surgery, increases the risk for marginal ulceration. Because of the association of H pylori and postoperative ulcers, the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has recommended that asymptomatic subjects who do not undergo preoperative endoscopy should undergo noninvasive H pylori testing, and if positive, they should be treated. When a marginal ulceration is present, the endoscopist should give careful attention to inspecting the gastric pouch, as presence of a gastrogastric fistula can result in increased acid exposure to the pouch and the jejunum. This, along with the absence of the usual bicarbonate buffer in the proximal duodenum as a result of the patient’s prior surgical procedure, may be a risk factor for ulcer formation. The role of endoscopy in dealing with marginal ulcers is typically for diagnosis; however, in cases where eroded suture material is present at the anastomosis, the suture material may be cut with endoscopic scissors and removed. Medical therapy for marginal ulcers consists of proton pump inhibitor therapy and sucralfate therapy, treatment of H pylori if found on biopsy, and avoidance of ulcerogenic medications. If the ulceration is particularly large or not responding to medical therapy, surgical revision may be required.

Management of Postbariatric Surgery Complications: Band Migration/Erosion and Slippage

The most common weight-loss surgical procedures that use a band that are encountered by endoscopists are the VBG and the LAGB. Gastric band erosion occurs in 1.6% to 3% of cases. Gastric band erosion is best diagnosed endoscopically. If an eroded band is encountered, as long as it is encapsulated, it can be cut with endoscopic scissors and removed. If there is doubt about encapsulation, it can be confirmed with a CT scan. It should be noted that endoscopic removal of an eroded band cannot be performed with adjustable gastric bands because there is tubing present that connects the band to a subcutaneous port used for band adjustment. Removal of adjustable gastric bands thus requires surgical intervention. Gastric band slippage is another potential complication and is best diagnosed with an upper GI series. Endoscopically, gastric band slippage manifests as an enlarged pouch size and, in severe cases, may lead to ulceration or even gastric necrosis, a potentially life-threatening condition.

Management of Postbariatric Surgery Complications: Anastomotic Leaks and Fistulas

Studies have reported that anastomotic leaks after RYGB occur in 0% to 5.6% of cases and are associated with high morbidity and mortality in the postsurgical patient. Anastomotic leaks generally present with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and tachycardia and are best diagnosed with an upper GI series. Intraoperative endoscopy has been proposed as a way to identify leaks intraoperatively so that they may be surgically repaired before completing the surgical procedure. In one study, intraoperative endoscopy was performed on 825 consecutive patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric procedures and 3.5% of the patients were found to have leaks that were then surgically corrected. In cases where chronic leaks or fistulas develop, surgical revision is often required. However, less-invasive endoscopic approaches have been described. Partially covered self-expanding metal stents, polyflex stents, argon plasma coagulation, endoclips, distal gastrojejunal stenosis dilation, and fibrin glue have all been used in the treatment of chronic leaks and fistulas.

Management of Postbariatric Surgery Complications: Loss of Effect of Surgery

Failure to lose weight or regaining previously lost weight after bariatric surgery may be the result of ingestion of high-calorie liquids or soft foods, gastric pouch dilation, large patulous gastrojejunal anastomosis, and gastrogastric fistula formation. Endoscopic therapies to reduce the size of a patulous gastrojejunal anastomosis have been described. One approach is to perform 4-quadrant injections of sodium morrhuate to induce scarring at the anastomosis. Another approach involves endoscopic placement and tightening of sutures at the rim of the gastrojejunal anastomosis leading to tissue placations, thus reducing the diameter of the anastomosis and potentially the size of the gastric pouch. Strategies for endoscopic management of gastrogastric fistulas have already been described earlier.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree