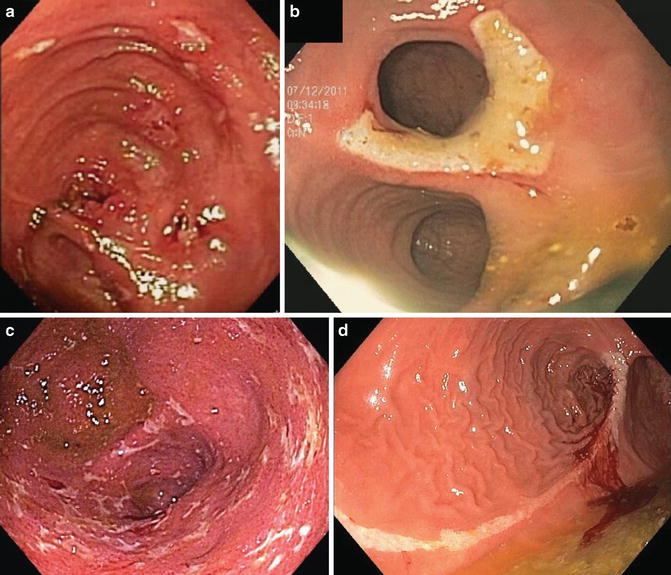

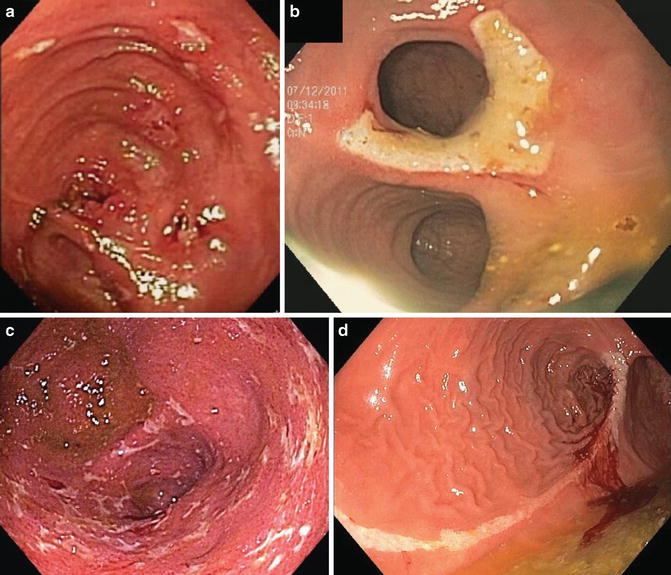

Fig. 15.1

Clinical phenotypes of Crohn’s disease of the pouch. (a) Inflammatory form (in the afferent limb). (b) Stricturing form (at the pouch inlet). (c) Fistulizing form (the orifices at the anal transitional zone). (d) Fistula with seton in place and drained perianal abscess

Patients’ gastrointestinal symptoms may be accompanied by extraintestinal manifestations such as uveitis, iritis, and arthralgia. In my personal experience, erythema nodosum more often occurs in patients with CDP than in chronic pouchitis. In contrast, pyoderma gangrenosum and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are more often seen in patients with chronic pouchitis than in CDP. In fact, the presence of PSC has been shown to be a protective factor for the development of CDP [3].

While clinical symptoms may provide clues for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of CDP, pouch endoscopy is the most important diagnostic modality. It should be pointed out that the disease process in CDP is not limited to the pouch body. In fact, it can involve any parts of the gastrointestinal tract, including stomach, proximal and distal small bowel, and cuff. There are other forms of inflammatory disorders of the pouch, mainly pouchitis and cuffitis. The differential diagnosis can sometimes be difficult. A careful evaluation of the pattern and distribution of mucosal ulceration and inflammation on pouchoscopy may yield clues for proper diagnosis (Table 15.1). Endoscopic features of CDP include discrete or segmental small and large ulcers, nodularity, exudate, and/or inflammatory pseudopolyps in the pouch body, afferent limb, or cuff or anal transitional zone (ATZ). Pre-pouch ileitis may be present in patients with pouchitis, and it is not necessarily indicative of CD. The presence of a long segment of enteritis above the pouch inlet in addition to diffuse pouch inflammation suggests that systemic, immune-mediated factors, such as PSC, contribute to the disease process [4]. The key features to distinguish CD ileitis from immune-mediated pouchitis/enteritis is the presence of an ulcerated and/or strictured pouch inlet and discrete (versus diffuse) mucosal inflammation in the former condition.

Table 15.1

Comparison of endoscopic features of Crohn’s disease of the pouch, pouchitis, and cuffitis

Crohn’s disease of the pouch | Pouchitis | Cuffitis | |

|---|---|---|---|

Pattern of inflammation | Discrete ulcers with or without adjacent inflammation | Diffuse homogenous inflammation | Discrete or diffuse inflammation |

Distribution | Discrete, can be in the pouch body, cuff, afferent limb, or upper GI tract | In pouch body with or without backwash enteritis | Cuff or anal transitional zone |

Stricture | Often | No | No |

Fistula | Yes | No | No |

Extraluminal disease | Yes, in fistulizing disease | No | No |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced injury to the pouch is common in patients with IPAA, resulting in inflammation, ulceration, and strictures (Fig. 15.2a). Those features overlap with those seen in CDP. The NSAID-induced mucosal inflammation typically does not respond to pouchitis-targeted antibiotic therapy and may resolve after the discontinuation of the drugs [5]. However, long-term use of NSAIDs can cause persistent ulcers or strictures in the small pouch, pouch inlet or outlet, or cuff, even after drug withdrawal. The NSAID-induced ulcers and strictures can be confused with CDP, even with proper evaluation with histopathology. Therefore, clinical history is important and patients should be advised to avoid NSAID use.

Fig. 15.2

Differential diagnosis of Crohn’s disease of the pouch. (a) NSAID-induced pouch ulcers that resolved after discontinuation of the agent. (b) Isolated ischemic ulcer at the pouch inlet. (c) Ischemic pouchitis with asymmetric distribution of the pouch body inflammation with a sharp demarcation at the suture line. (d) Long superficial ischemic ulcer along the suture line

Another challenging issue is the presence of the confounding factor of surgery-associated ischemia. Ischemic injury from surgery can result in virtually the same pattern of inflammation, ulceration, stricture, and fistula as in CDP. Like in CDP, the surgery-induced lesions may be present in the distal afferent limb, inlet, pouch body, anastomosis, and cuff or ATZ (Fig. 15.2b). Chronic pouchitis with the contributing factor of ischemia may also be associated with transmural inflammation [6]. Ischemic pouchitis is characterized by the endoscopic appearance of non-diffuse, asymmetric disease distribution, with a sharp demarcation of the inflamed part and non-inflamed part at the suture line (Fig. 15.2c) [7]. Another pattern of inflammation in ischemic pouchitis is the presence of inflammation only in the distal pouch but not in the proximal pouch. This is often seen in obese male patients.

The most common locations for strictures in patients with IPAA include the site of previous loop ileostomy, the pouch inlet and the pouch outlet. The main causes for these strictures are CDP, NSAID (Fig. 15.2a), and surgery-induced ischemia (Fig. 15.2b, c). The endoscopic appearance of the stricture is not helpful for the differentiation diagnosis. The presence of strictures outside these 3 common locations may suggest a diagnosis of CDP, such as those in the middle pouch body, proximal afferent limb, and duodenum.

Not all fistulas in patients with IPAA result from CDP. The most common locations in fistula pouch patients are pouch-vaginal fistula (PVF), perianal fistula, and enterocutaneous fistula. The most frequent causes of fistulae are Crohn’s disease, ischemia, iatrogenic injury, and cryptoglandular abscess. During a stapled anastomosis procedure, entrapment of the posterior wall of the vagina can result in a pouch vaginal fistula. Anastomotic leaks can cause PVF anteriorly or a presacral sinus posteriorly. A leak at the tip of the “J” leak or loop ileostomy site can lead to enterocutaneous fistula. Inflammation of the anal glands also can result in an abscess and perianal fistula. Those non-CD related conditions are difficult to distinguish from CDP. It is important to identify the fistula opening from the pouch side and delineate the length and configuration of the fistula. This can be achieved by the use of an endoscopic guidewire or spraying hydrogen peroxide or methylene blue. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis or examination under general anesthesia in the operating room may provide confirmatory information. The presence of the following features suggests the diagnosis of CDP:

1.

Fistula opening in the mid anal canal, outside of the anastomosis or dentate line

2.

Inflammation around the fistula opening

3.

Complex fistula; i.e., multiple fistulae or branched fistula

4.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fistula and inflammation and ulcers at separate locations of the pouch (Fig. 15.3).

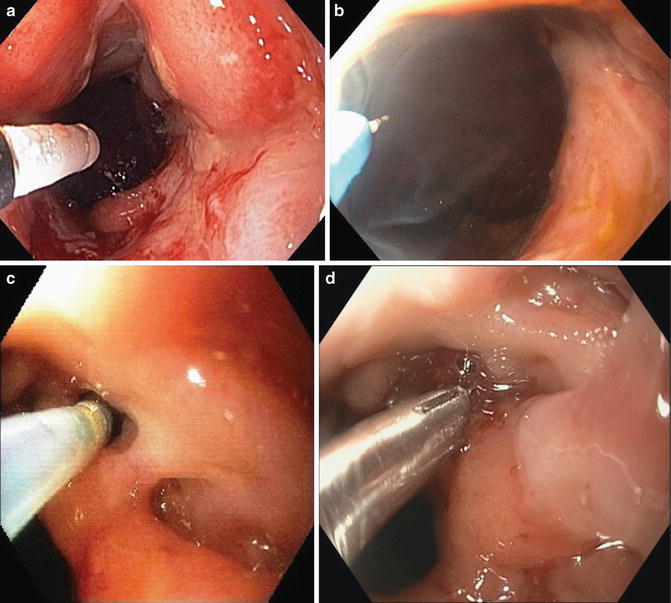

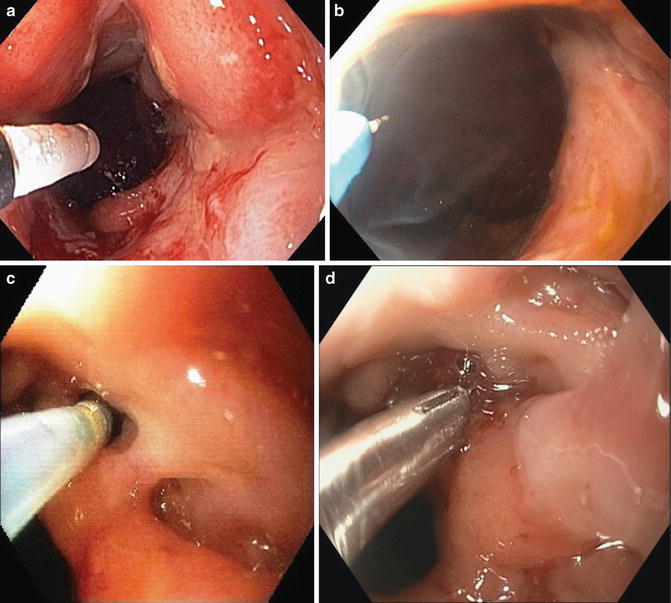

Fig. 15.3

Endoscopic therapy for stricture and fistula: (a) Balloon dilation of anastomotic stricture. (b) Needle knife stricturotomy of anastomotic stricture. Notice that the therapy was only delivered to the posterior aspect of the anastomotic stricture, not the anterior aspect. (c) Infusion of 50 % dextrose through the orifice of pouch-vaginal fistula with a catheter. (d) Deployment of an endoclip at the orifice of a vaginal fistula

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree