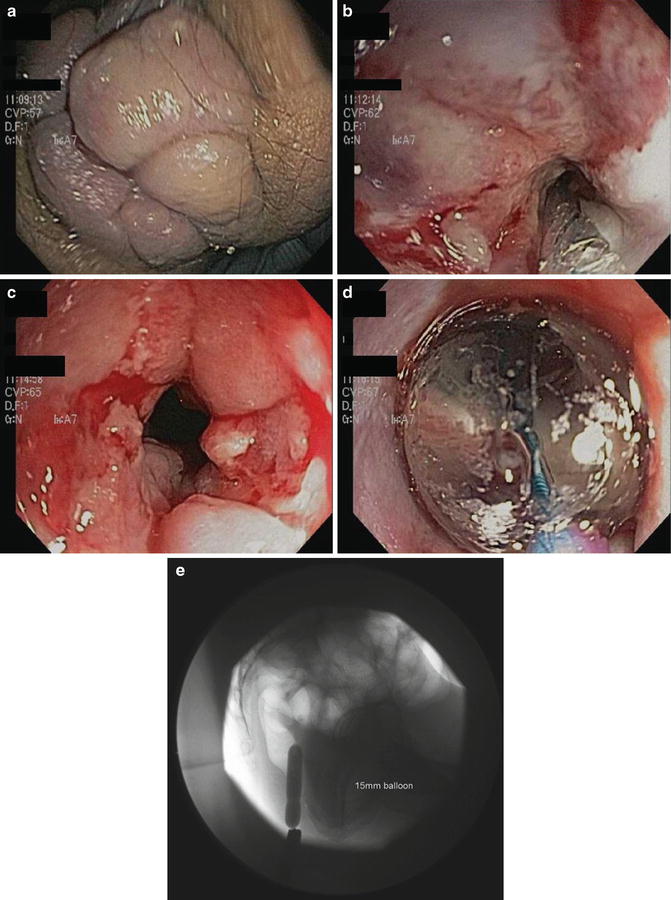

Fig. 21.1

(a, b, c) High-grade jejunal strictures resulting in markedly dilated proximal jejunal loops. Length of stricture/multiple strictures and degree of upstream dilation and damage make surgery a much better option than endoscopic therapy in this patient.

Fig. 21.2

Approach to endoscopic management of IBD-related strictures.

Endoscopic Balloon Dilation

Stricture dilation using a through-the-scope (TTS) balloon dilator may be an alternative to surgery for patients with CD-related benign, pan-enteric strictures. Typically, this is reserved for patients with short (<4–5 cm), symptomatic (obstructive symptoms), predominantly fibrostenotic or anastomotic strictures, without associated fistulous tracts or abscesses.[8] Hence, initial evaluation should focus on assessing the presence of active inflammation contributing to narrowing of luminal diameter—reduction of transmural edema using anti-inflammatory therapy can significantly increase luminal cross-sectional area and result in marked improvement in obstructive symptoms, obviating stricture dilation. Balloon dilation has also been used for pouch-related strictures after ileal pouch anal anastomosis in UC.[9]

There is no uniform technique of TTS balloon dilation of IBD strictures, but generally follows the same principle of any benign stricture dilation throughout the intestinal tract.[10] Bowel preparation and sedation is the same as for a normal colonoscopy, and periprocedural antibiotics are not required. It is advisable to use balloons 5–8 cm in length to decrease the risk of displacement during insufflation. The balloon is gradually introduced into the stricture, under direct visualization, with or without a guidewire (Fig. 21.3) (Video 21.1). Subsequently, graded dilation using multistep balloons is performed, using water to fill to recommended ideal pressure. Protocols are variable with regard to time of dilation (1–4 min) and frequency of dilation (1–6 times/session). There are no set standards for use of wire-guided versus non-wire guided dilation and use of fluoroscopy. When feasible, retrograde dilation with passage of scope beyond the stricture and working backward is preferred over blind antegrade dilation, to minimize risk of adverse events. Wire-guided stricture dilation is typically used for angulated strictures or tight strictures, through which a scope is not able to pass (Fig. 21.4) (Video 21.2). For small bowel-strictures, deep enteroscopy using balloon-assisted endoscopy has been used to perform TTS stricture dilation. In a systematic review of 13 studies in 347 patients with CD-related strictures who underwent pneumatic dilation, the technique varied widely across studies with regard to balloon size (maximum, 18–25 mm in studies), use of graded dilation (used in 8/13 studies), duration of balloon dilation (<1 minute to >3 minutes), number of dilations/session (1–4), and number of sessions per patient (average, 2.2/patient).[11]

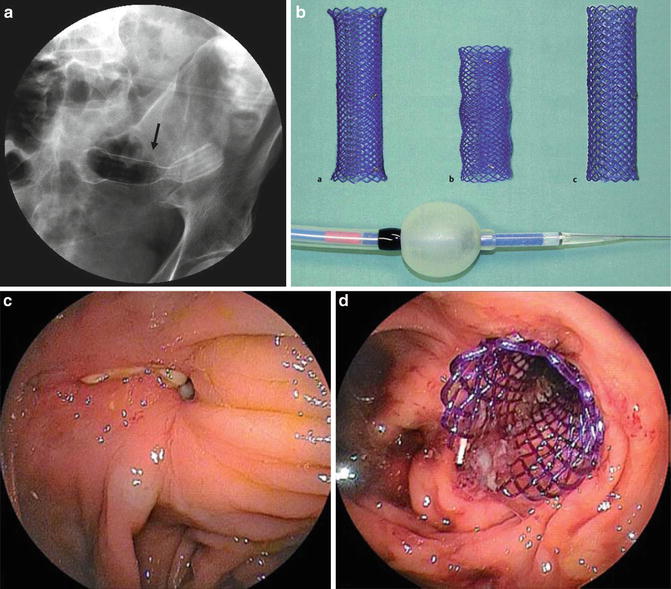

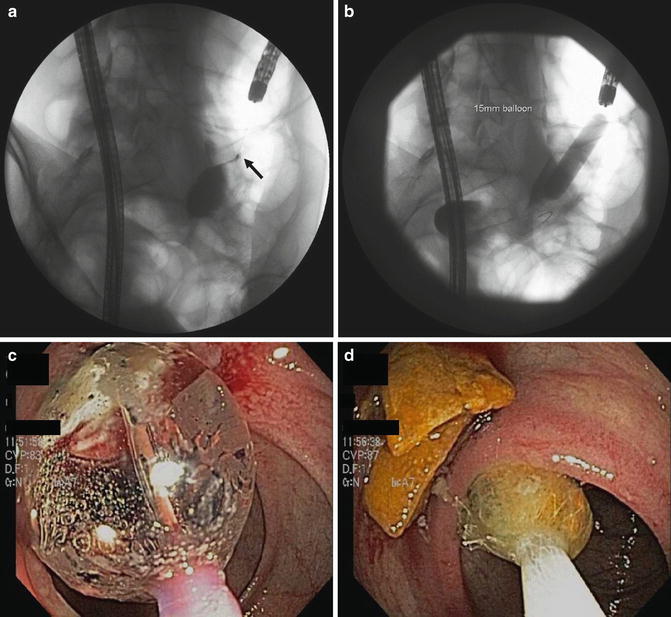

Fig. 21.3

(a, b, c, d) High-grade anal stenosis in patient with additional anastomotic Crohn’s. (e) Anal canal dilated to 15 mm using CRE balloon. Note huge hemorrhoids. Accompanying Video 21.1 demonstrates spontaneous drainage of perirectal abscess following balloon deflation.

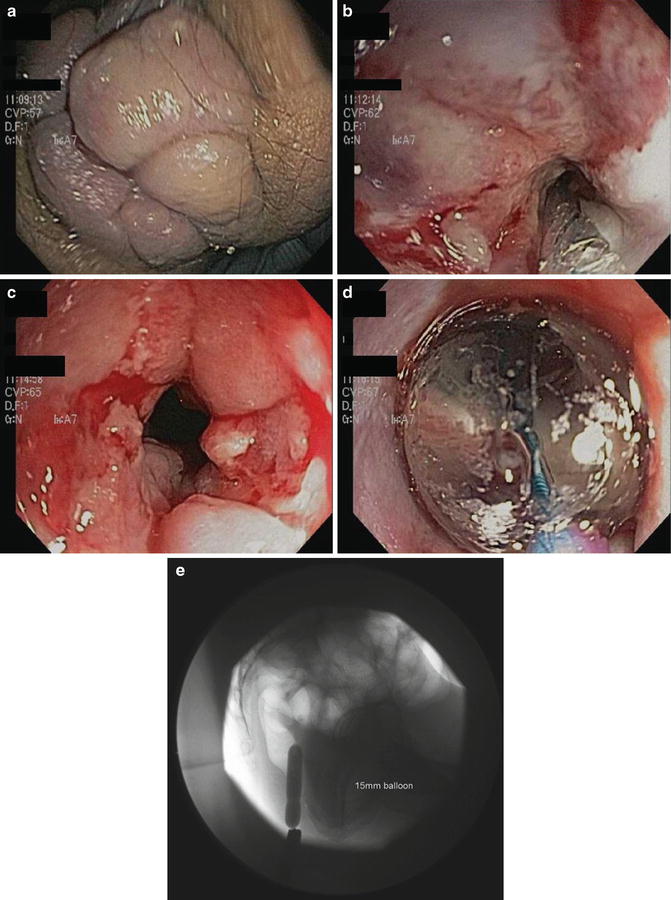

Fig. 21.4

(a) Tight anastomotic stricture in an end-to-side ileocolonic anastomosis (arrow). (b) Contrast injection beyond stricture dilated with 12–15 mm CRE balloon. Accompanying Video 21.2 demonstrates second stricture that was dilated 12–13.5 mm followed by removal of upstream enteroliths (c, d).

The technical feasibility and efficacy of dilation is also variable. On systematic review of fibrostenotic CD in 347 patients in 13 studies (mean age, 54 years; 54 % female; mean time from CD diagnosis to development of stricture, 13 years; mean stricture length, 2.7 cm, range, 0.5–20 cm, with 65 % being <3 cm and 84 % being <5 cm), balloon dilation could be accomplished in 86 % (range, 45–100 % in individual studies) of patients.[11] In others, TTS dilation was technically unsuccessful due to inability to reach the stricture with the endoscope or in passing the balloon through an angulated stenosis; 89 % of these patients underwent surgery. Short-term technical success was achieved in 71–100 % of patients. At mean follow-up of 33 months, long-term clinical efficacy (defined as surgery-free at end of follow-up) was achieved in 58 % of patients (68 % of those in whom dilation was technically feasible), ranging from 50–100 % in individual studies. Approximately 59 % of the responders avoided surgery until the end of follow-up after a single session, 22 % required two sessions, whilst the remaining 19 % required more than two dilatations, ranging from 3 to 18. Surgery was ultimately necessary in 144 (42 %) patients. The mean interval between endoscopic dilatation and surgery was 15 months (range, 1–70 months). Subsequently, in a large series of 138 patients with fibrostenotic CD who underwent 237 dilations (mean age, 51 years; 56 % female; 84 % anastomotic; all strictures <5 cm in length), technical success (defined as ability to pass an adult colonoscope through the stricture after dilatation) was accomplished in 97 %.[12] After a median follow-up of 5.8 years (interquartile range, 3.0–8.4y), 44 % did not require any additional procedures until end of follow-up (dilation- and surgery-free); recurrent obstructive symptoms after the first dilation led to repeat dilatation in 46 % or surgery in 24 %, with a median time to next procedure of 12.5 months (IQR, 6–21.5 m). In another series of 776 dilations in 178 patients of whom 75 patients had >5 year follow-up, cumulative risk of surgery after dilation was 13 % and 36 % at 1 year and 5 years after dilation.[13] In an observational study of 167 patients with ileal pouch strictures who underwent stricturoplasty (10 %) or endoscopic balloon dilation (90 %), there were similar rates of stricture recurrence (56.3 % versus 55.0 %, respectively) after a mean follow-up of 4.1 years, although the response was more durable with stricturoplasty.[14] Factors influencing outcome after endoscopic balloon dilation in fibrostenotic CD are largely unknown. Technically successful dilation, stricture length of 4 cm or less and the absence of ulcer in the stricture have been positively associated with successful dilatation.[8] The data on smoking are inconsistent. In contrast, C-reactive protein, endoscopic disease activity or medical treatment after dilation, seem to influence the subsequent disease course.

Some investigators have advocated intralesional steroid injection after dilation, based on retrospective observational studies (Fig. 21.5). This technique has been used with success in other stricturing gastrointestinal conditions such as peptic, corrosive or anastomotic strictures or fibrosis post-radiotherapy. However, findings from two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conflicting. In an RCT of 29 pediatric patients with fibrostenotic CD, Di Nardo et al. observed that only 1/15 patients with intramucosal triamcinolone injection (40 mg, 4-quadrant injection at 2-cm intervals) required redilation (0/15 required surgery) as compared to 5/14 receiving placebo (4/14 required surgery).[15] The time to redilation was also longer in patients who received steroid injection (steroid versus placebo, median: 11.7 versus 9.4 months). However, contradictory results were observed in another RCT of 13 adult patients with fibrostenotic CD.[16] Five (out of 7) steroid-treated patients required re-dilation, as compared to 1/6 placebo-treated patients. However, all these patients had long-standing (8–30 years), anastomotic strictures. Hence, additional studies are warranted before intralesional steroid injection after balloon dilation can be routinely recommended for patients with fibrostenotic CD. Small, uncontrolled, case series have also suggested that intra-lesional injection of infliximab may be considered for refractory strictures with limited success, although this data is hard to interpret.[17]

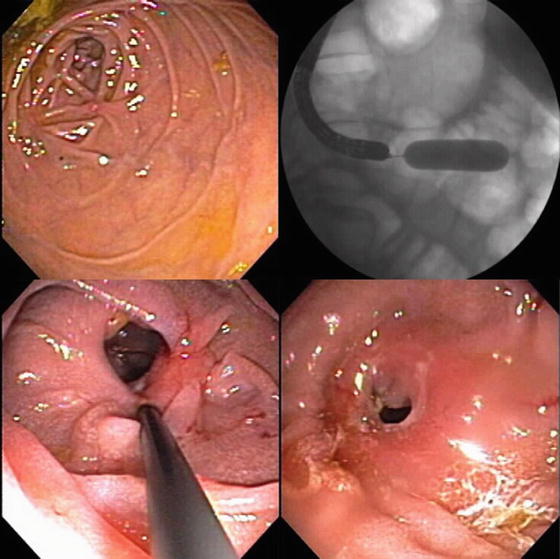

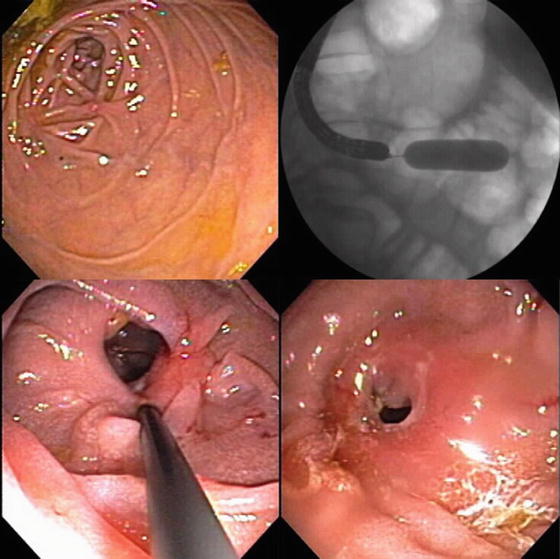

Fig. 21.5

Steroid injection into tight anastomotic stricture following balloon dilation.

Endoscopic balloon dilation is generally safe, but the risk of adverse events is higher than conventionally reported in the general population. In the same systematic review, serious adverse events (defined as bleeding, perforation, infection or other event leading to hospitalization) were observed in 14/695 dilations (rate, 2 % per dilation; 4 % per patient), with perforation rate of 1.9 % per dilation.[11] In another series of 237 dilations in 138 patients, 12 serious adverse events (6 perforations) were observed (rate, 5.1 % per dilation; 8.7 % per patient); all 6 patients with perforation required surgery. In another series of 178 patients who underwent 776 dilations, overall adverse event rate per procedure was 5.3 %, including perforation rate of 1.4 % and major bleeding requiring blood transfusion rate of 1.0 %; there was no procedure-related mortality.[13]

Endoscopic Needle-Knife Stricturotomy

Electroincision using a needle-knife has been conventionally used for precut sphincterotomy in patients with difficult biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). It has also been used for refractory esophagogastric anastomotic strictures before balloon dilation [18] and in congenital pylori stenosis.[19] In a recent study from Cleveland Clinic, endoscopic needle-knife stricturotomy has been performed for ileocolonic and ileal pouch strictures, in patients with fibrotic strictures refractory to repeat balloon dilation.[20] The technique involves use of a TTS catheter-based Doppler ultrasound probe to localize low-flow areas within the stricture. Then, an ERCP sphincterotome is used to dissect the fibrotic stricture, avoiding areas of high vascularity. This technique has been useful, in highly specialized centers, for strictures requiring repeated balloon dilation, with acceptable rates of adverse events.

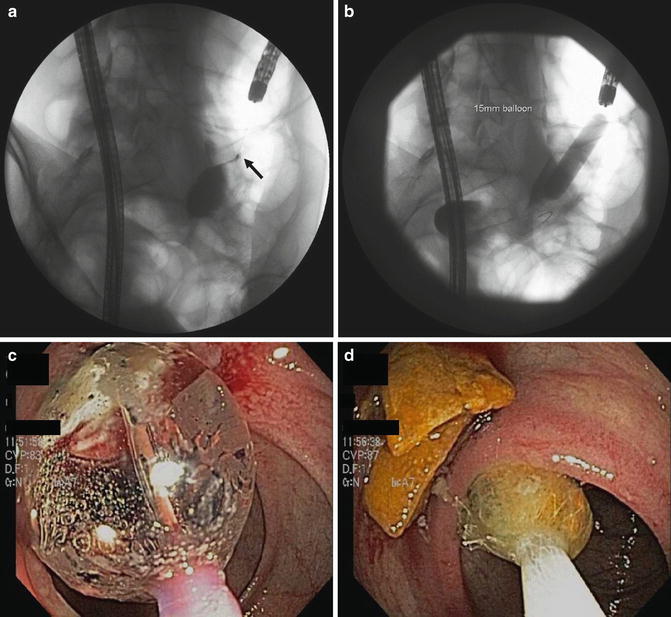

Endoscopic Stent Placement

In patients with fibrostenotic CD or with anastomotic strictures, self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) have been used with limited success (Fig. 21.6a). In a series of 17 patients with fibrostenotic CD, 25 stents (21 fully covered SEMS, four partially covered SEMS) were placed in strictures 2–6 cm in length, after failure of repeated endoscopic balloon dilation, and were kept in place for 28 days (range, 1–112 days).[21] SEMS placement was technically successful in 16/17 patients. After a mean follow-up of ~16 months, the treatment was successful (symptom-free at end of follow-up) in 65 % of patients. The recurrence rate after the therapy in patients with technical success was 44 %, after a mean follow-up of 14 months (range, 3–30 months). While there were no immediate adverse events of bleeding or perforation, four patients developed stent impaction with difficulty in stent removal not unexpectedly with partially covered SEMS. Thirteen of the 25 stents (52 %) spontaneously migrated distally primarily due to resolution of the underlying stenosis, and hence, may not be considered a procedural adverse event. In another French series, SEMS placement was attempted in 11 patients, with technical success in 10 patients.[22] Of these, 60 % had improvement in obstructive symptoms; however, two patients required surgery to address adverse events related to stent placement. Development of an anti-migratory system within the stent may decrease risk of migration; these stents do, however, require removal after intended utility.[23] The use of endoscopic suturing devices to anchor stents in place has not been studied for CD-related strictures.