Endoscopic Separation of Components

Ashley H. Vernon

Ryan R. Gerry

Ramirez published his experience with the “separation of components” procedure in 1990 for the closure of complex abdominal wall hernias, and since this time the use of component separation has become widespread for this indication. His original paper describes complete mobilization of the external oblique muscle and its aponeurosis from the rectus and internal oblique which resulted in the ligation of perforators of the deep inferior epigastric artery and deep circumflex iliac artery to the overlying skin. The Achilles heel of this procedure is that it creates skin flaps that are relatively ischemic, which makes these flaps prone to wound problems, including superficial wound infection and necrosis. Modifications of the original procedure that preserve the perforating vessels to the overlying flaps have been adopted in attempt to preserve the perfusion to the overlying flaps and reduce these complications.

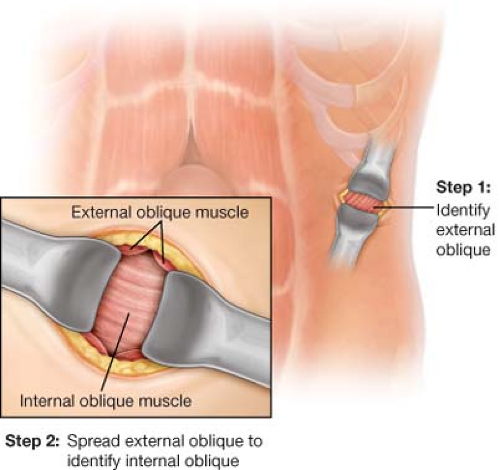

Endoscopic release of the external oblique aponeurosis and component separation, otherwise known as bilateral endoscopic component separation (BECS), incorporates several improvements in technique which reduce complications inherent to the open procedure. The most significant improvement is that the perforating vessels are not disrupted and there is no soft tissue undermining.

Additionally, the incisions used to create the release are separated from the midline wound which ensures that any wound complications created by the release will not undermine the primary repair.

The durability of the open component separation is well documented with wound healing rates approaching 100%, even in contaminated wounds. The longevity of the repair, however, is less certain and may depend upon augmentation with permanent mesh. The endoscopic component separation draws on the strengths of the open version as it has been demonstrated to have similar physiologic and anatomical characteristics.

BECS is gaining popularity because of lower wound complication rates compared with the open technique. The past decade has been notable for an increased availability of bioprostheses that can be used in contaminated wounds. Experience with these products has highlighted the need to restore the muscular function of the

abdominal wall. Combining BECS and underlay mesh to reinforce a primary closure at the midline achieves the best functional outcome with the lowest perioperative complications.

Indications for BECS with ventral hernia repair, include but are not limited to (1) contaminated hernias in which permanent mesh is contraindicated, (2) moderate to large-sized ventral hernias, and (3) hernia-associated symptoms due to large abdominal wall deformity, for which primary closure of the abdominal wall in the midline will restore normal abdominal contour.

Prior surgery of the lateral abdominal wall may pose difficulty with dissection due to adhesions. It is impossible to develop the plane between the oblique muscle layers when they are fused at an old wound. The most commonly encountered lateral deformities which prohibit BECS are open appendectomy scars and stoma sites.

In the elective setting, nutrition is maximized with enteral or parenteral feeding; infection should be adequately treated; and obese patients have lost weight under the guidance of a dietitian and surgeon.

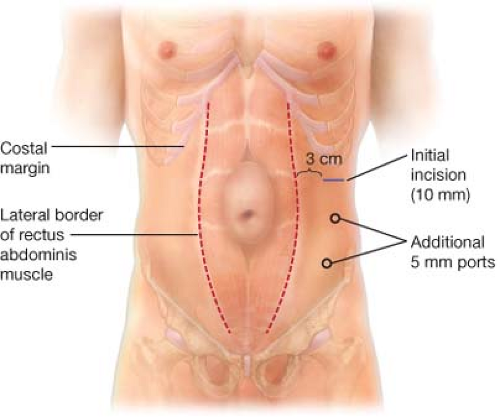

Preoperative abdominal CT assists in determining the size of the abdominal wall defect and in identifying the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscles.

Positioning

The patient should be in the supine position with a wide surgical field, including the costal margins and the lateral abdominal wall.

Tucking both arms at the patient’s side is helpful since both the surgeon and assistant may be more comfortable standing on the same side.

Anesthesia

General anesthesia is routine when repairing hernias of sufficient size to require separation of components.

Prophylactic antibiotics to cover gram-positive organisms should be administered within 60 minutes of incision and re-dosed according to hospital antibiotic guidelines throughout the case.

A urinary catheter is useful to decompress the bladder and helps avoid injury to the bladder when dissecting in the pelvis.

Technique

Port placement and development of the dissection plane:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree