Preoperative Planning

■ ERCP is usually performed as an outpatient procedure, but postprocedural observation may be prolonged due to the potential complexity of the procedure as compared to other standard endoscopic procedures.

■ Prior to initiation of the procedure, the endoscopist should be absolutely certain of the indication of the procedure taking into account all of the preprocedural workup. The importance of having a well-defined therapeutic goal for the procedure cannot be overemphasized. ERCP should not be performed for diagnostic purposes only.

■ Informed consent should be obtained, explaining all the potential benefits, risks, and alternatives. This should include a discussion of the risk to that individual patient, taking into account the patient and procedural factors which influence the rate of postprocedure complications.

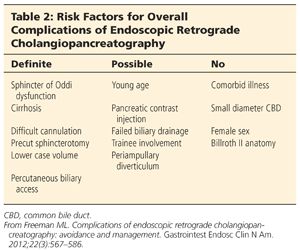

■ Table 2 details risk factors for overall complications of ERCP.

■ Patients are kept NPO overnight prior to the procedure. Antibiotics with broad-spectrum coverage should be considered periprocedurally in only limited circumstances of biliary ductal obstruction or transpapillary pancreatic pseudocyst drainage.

Positioning

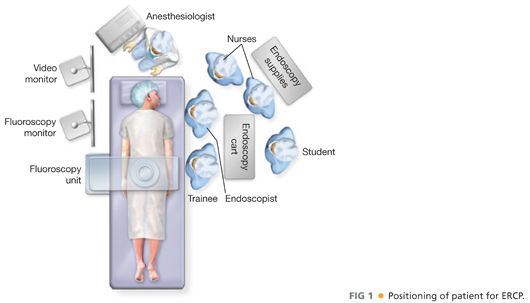

■ The patient lies in a left semiprone position on the fluoroscopy table with both arms at their side. The right chest/shoulder is usually propped up slightly so that the head faces the endoscopist (FIG 1). A plain radiograph (scout film) is usually taken to ensure the field is clear of any radiopaque material such as monitoring wires and to document the presence/absence of any devices such as drains, stents, feeding tubes, and so forth.

■ Sedation can be either conscious sedation (combination of benzodiazepine and opiate) administered under the supervision of the endoscopist or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). Most units now use either MAC or general anesthesia, depending on patient and case specifics.

TECHNIQUES

■ Depending on the indications, various maneuvers may be performed during ERCP. However, passage of the scope to the major papilla in the duodenum and selective cannulation of the desired duct is essential to every successful ERCP.

INTUBATION OF ESOPHAGUS AND PASSAGE OF SCOPE TO DUODENUM

■ Because the duodenoscope is a side-viewing instrument, passage through the oropharynx and esophagus is more by feel than direct visualization. Before intubation, ensure that instrument is in proper working order. The up-and-down and lateral movement dials should be unlocked and the elevator checked to ensure proper functioning; the elevator should be in a relaxed (down) position during insertion. The light source and attachments to the scope, that is, irrigation, suction, insufflation should be checked. Once the patient is adequately sedated, the back of the scope is lubricated (taking care not to smear over the lens) and the scope is guided over the patient’s tongue to the upper esophageal sphincter. With gentle pressure, the scope should pass into the patient’s esophagus and down to the stomach. If any abnormal resistance is encountered while intubating the esophagus, the scope should not be forced. It may need to be removed and the anatomy reviewed with a forward-viewing gastroscope.

■ Once the scope enters the stomach, slight air insufflation may be required to orient the tip toward the antrum. The scope is then passed along the greater curvature toward the pylorus. Once the exact location of pylorus is determined, the scope tip is angled upward and advanced through the pylorus. Because of the side-viewing nature of the scope, the pylorus will not be seen as the scope passes through it.

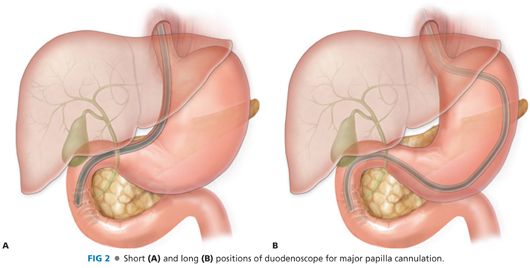

■ The scope is then passed carefully under direct vision to the level of the second portion of the duodenum. Full forward vision is not possible with this scope, and duodenal perforation is possible if an attempt is made to obtain a full forward view of the lumen. At this point, the scope is usually in a “long position.” A shortening maneuver is performed by torqueing the scope shaft clockwise and pulling the scope out of the patient’s mouth while the right wheel is locked in a full rightward position. This usually leads to paradoxical forward motion of the scope tip such that the scope ends up in the preferred “short position” (FIG 2). From this position, small adjustments can be made with a combination of movement of up-and-down and lateral movement dials as well as the endoscopist changing his/her stance slightly left or right. These motions ultimately bring the major papilla into an adequate en face cannulating position. At this point, depending on endoscopist preference, the scope dials may be locked for a more stable position.

MAJOR PAPILLA CANNULATION

■ Selective cannulation of the desired duct is the most important and most difficult skill to master for successful ERCP. Knowledge of normal papillary anatomy is essential, as is adequate training and experience. The most common reason for failure is inability to cannulate the duct of interest. Studies suggest that 180–200 cases in training are necessary before even moderate rates of cannulation are achieved.2 Furthermore, it has been suggested that it takes about 1000 cannulations to become truly comfortable with the technique and several thousand more to become expert.3 Various cannulation techniques have been described but all involve the use of catheters and guidewires. Typically, catheters with cutting wires (sphincterotomes) and preloaded guidewires are used for therapeutic ERCP. Another general principle is to avoid too much contrast injection until the endoscopist is reasonably sure that the cannulating device is at least superficially in the desired duct. This serves to avoid too much fluoroscopic exposure, avoid submucosal injection, and reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

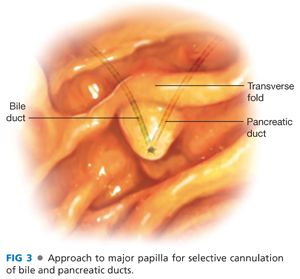

■ Selective biliary cannulation is initially achieved by superficially probing the major papilla usually at the 10 o’clock to 12 o’clock position, thereby staying superior to the intraductal septum and aiming the catheter upward (FIG 3). Once the catheter tip has advanced slightly into the duct orifice, either the guidewire can be advanced further or contrast can be injected to confirm position. If inadvertent pancreatic duct cannulation is achieved, it is important to avoid or limit any contrast injection (unless pancreatic duct cannulation is desired). Once superficial biliary cannulation is confirmed, the guidewire is advanced further proximally into the duct followed by catheter advancement to achieve deep cannulation.

■ Selective pancreatic cannulation is achieved by approaching the papilla generally at its center but aiming at the 2 o’clock position. This usually aligns the catheter tip axis below the septum toward the pancreatic duct orifice (FIG 3). Using a combination of guidewire and catheter advancement, deep cannulation can be achieved. An important aspect is to limit contrast injection to small amounts so as to avoid acinarization of the pancreas, thereby decreasing the potential for post-ERCP pancreatitis.

■ In certain instances where selective cannulation of the desired duct may not be easily achieved due to abnormal or pathologic anatomy (such as periampullary diverticulum, malignancy, postsurgical anatomy), special techniques and/or devices may need to be used. These may include performance of a “precut” or “access” sphincterotomy, use of rotatable cannulating devices, placement of a pancreatic stent (to facilitate biliary cannulation and reduce risk of postprocedure pancreatitis), and the use of specific guidewires which may differ in caliber or hydrophilic nature. In certain cases of postsurgical anatomy, ERCP may be impossible with duodenoscopes. In these instances, enteroscopes (device or nondevice assisted) may be required, which can make the procedure more technically challenging. Patients who have undergone bariatric surgery in whom the stomach and proximal small bowel is bypassed pose a special challenge. In such patients, the procedure can be attempted with enteroscopes, but laparoscopic-assisted ERCPs (with the assistance of a surgical team) are becoming the preferred approach.

■ In patients whom biliary cannulation is initially unsuccessful, the procedure can be reattempted in a day or two if the clinical situation allows. Referral to a center with expertise in ERCP is also reasonable. However, if delay is not feasible, patients generally proceed to percutaneous biliary catheter placement by interventional radiology. Depending on case specifics and endoscopist expertise, EUS-guided biliary access can be performed too.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree