Endoscopic

Surgical

Risks of complications of resection

Low

High

Risks of future cancer

Continues

Nil in proctocelectomy

Needs of continuing surveillance

Yearly at least for 5-years post-resection

None in UC

Continues in Crohn’s Colitis

Potentials for bowel habit change

Nil

Significant change in patients with controlled disease

Lesion Assessment

Determination of Lesion Margin

Accurate assessment of the lesion margin is a critical first step. Endoscopic resection is only appropriate for lesions that have clearly defined borders; i.e., they are clearly circumscribed. For small lesions where immediate resection is often preferred, photo-documentation after chromoendoscopy, and after lesion resection, with biopsies around the resection site are appropriate. For larger lesions, where there is concern regarding high-grade dysplasia or cancer and the dysplastic nature of the lesion needs to be confirmed, a single biopsy of the lesion itself would ideally be taken to avoid “welding” the lesion to the submucosa even further due to biopsy-associated fibrosis. This should be taken from the most suspicious area of the lesion such as a depression or an area with loss of pit pattern (see later). The endoscopist who found the lesion should provide photo-documentation and pathology results. Image-enhanced endoscopy using chromoendoscopy or other techniques are typically necessary in order to visualize and confirm that the lesion is circumscribed (Fig. 20.1a–c). Even if a clear border can be seen, it is appropriate to take biopsies around the resected site or the lesion when the lesion is discovered to look for endoscopically invisible dysplasia.

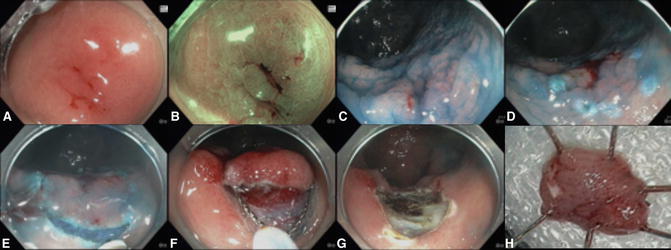

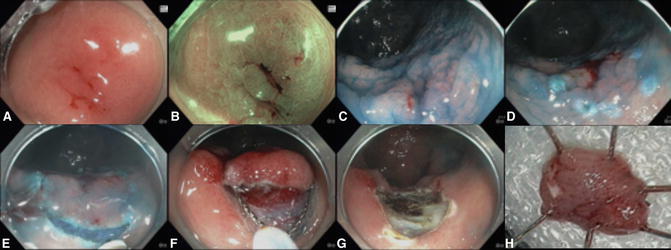

Fig. 20.1

The resection of a superficial flat (Paris 0-IIb) lesion can be challenging. (a) The lesion was detected because of its reddish appearance. The spontaneously bleeding site was the site of prior biopsy, which showed low-grade dysplasia (LGD). (b) The neoplasm appeared slightly more brownish under Narrow Band Imaging (NBI). Note, however, that NBI is not beneficial to detect the nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Pit-pattern analysis under NBI or indigo carmine is also not useful to differentiate neoplastic and non-neoplastic. (c) The circumscribed edge of the lesion is well seen with chromoendoscopy. (d) Periphery of the lesion was marked prior to submucosal injection. (e) Circumferential incision was performed using the Dual Knife. (f) The isolated lesion was resected using a snare. (g) The site of resection. (h) The resected specimen. The pathology showed low-grade dysplasia

Assessment of Potential Invasion

Accurate assessment of the potential for invasive cancer follows the assessment of lesion margin. The lesion should be carefully examined once completely clear of stool and mucus. Typically, a higher concentration of dye for chromoendoscopy is used in order to improve visualization of subtle changes [20], which may indicate the presence of invasive cancer: a large nodule, a depression, loss of pit pattern (Kudo type V), and a mass-like appearance [21]. The presence of any of these signs is a red flag of whether endoscopic resection is appropriate. A perforation of a T1 or T2 cancer during ill-advised resection due to mistaken assessment leading to a by-definition T4 cancer is a clinical tragedy, and usually an avoidable one. Unfortunately these observations, which are reasonably reliable in non-colitic colons for experienced operators, perform less well in colitis as the scarring may lead to pseudo-depression and inflammation distorts crypt openings and pit patterns. While the non-lifting sign has a good specificity for invasive cancer in non-colitic neoplasia, the non-lifting sign is often of limited value because of the sub-mucosal scarring due to chronic colitis [22].

Lesion Location in Difficult Areas of the Colon

Location of the lesion close to areas that might make resection more difficult should also be considered such as the appendix orifice, around the ileo-caecal valve, at a flexure, especially on the inside of the bend, and near the dentate line [23]. Although polyps in all of these positions can be resected in non-colitis colon scan by experienced endoscopists, the technical difficulty is substantially increased. In combination with the other difficulties that lesion in colitis represents, this may make the likelihood of a curative resection so low that an endoscopic attempt may not be appropriate.

Endoscopic Access

The final stage to consider is endoscopic access. This is one of the few areas where working in a colitic colon may have advantages as a scarred and tubular colon makes for a straight endoscope, allows accurate tip deflections, and a lack of haustral folds to be negotiated. Before starting, the endoscopist should be satisfied that he/she could easily reach all areas of the lesion with precision.

There is no specific combination of factors or scoring system that suggests whether lesions are or are not safely and effectively resectable. The risk needs to be individualized according to patients’ preferences and endoscopists’ skills. Ultimately it comes down to the experience and judgment of the endoscopist. Given the fine nature of these judgments, we would recommend that, if possible, the endoscopist who is going to do the resection procedure should perform the endoscopy for lesion assessment prior to resection unless excellent comprehensive images are available.

Colonic Assessment for Disease Status

It is important to consider the rest of the colon before committing to endoscopic resection of a lesion. Performing chromoendoscopy to rule out other lesions is mandatory and although it is generally assumed that the lesion is single, the referring endoscopist may not have assessed the remaining colon using chromoendoscopy. For example, a young patient with multifocal dysplasia may benefit more from surgery.

It is also important to consider the level of disease activity both past and present. Severe inflammation in the past is likely to lead to significant scarring of the submucosa. Lesions that have undergone a previous attempt at resection, recurrence on a scar from previous EMR or non-granular type laterally spreading tumor (LSTs) are examples from non-colitis resection practice that may mimic the severe scarring and increase risk of resection [24]. If the patient has a very tubular colon with evidence of scarring, post-inflammatory polyps, loss of vascular pattern even in remission, or active inflammation, the sub-mucosal scarring is likely to be severe and typically involves the entire lesion. This impedes lesion lifting and makes identification of the submucosal plane difficult.

Active disease is a risk factor for future dysplasia, makes identification of other dysplastic lesions more difficult, and makes edges more difficult to detect. If at all possible, resection should be undertaken in remission and strenuous efforts to achieve this should be made. If reasonable remission cannot be achieved even for a short time, the decision that endoscopic resection was more appropriate than colectomy should perhaps be revisited.

Co-morbidity

As well as taking into account a patient’s wishes regarding colectomy and cancer risk, the endoscopist also needs to weigh the patient’s co-morbidities and lesion difficulty against the likely outcome of a perforation, and severe bleeding. Although co-morbidities may preclude surgery, careful thought is needed as to whether a difficult endoscopic attempt at resection, for a low-risk lesion, in a patient with severe co-morbidities is really likely to extend or improve the quality of their life. Such an attempt may, in fact, reduce it. The best option may be masterly inactivity. The decision may need to be made to terminate a resection even during the resection if the risk seems to be increasing.

Endoscopic Resection

Lesions that lie outside the colitis segment, as assessed both endoscopically and histologically, can be viewed as sporadic lesions and approached with standard techniques. Here we consider dysplasia as neoplasia occurring within the colitis segment.

There are three key principles to be considered for endoscopic resection in colitis:

1.

The patient’s colitis should be in remission.

2.

Confirm the lesion is circumscribed with no surrounding dysplasia using dye-spray and margin biopsies.

3.

Aim for en bloc resection where possible, which may involve en bloc endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or local surgical excision (TEM or laparoscopic disc excision).

Small Lesions ≤ 10 mm

In general small dysplastic appearing lesions, either polypoid (Paris classification 0-Is or Ip) or non-polypoid (Paris 0-IIa, IIb or IIc), within the segment of colitis can be endoscopically resected at the time of detection, but after assessment of the border and extent with chromoendoscopy. Care should be taken to ensure complete excision. EMR can be very useful to resect small non-polypoid lesions en bloc, although the stiffer mucosa of colitis might make resection more difficult. A digital image of the lesion pre-resection with dye-spray, and biopsies from around the lesion are very helpful when discussing the patient’s case subsequently in the IBD MDT.

Larger Lesions > 10 mm

Larger polypoid and non-polypoid, including the laterally spreading tumours (LSTs), are more complex to resect. The risk of residual dysplasia after the resection of non-polypoid lesions is probably higher [25] as in the large non-colitic tumors. The risks and benefits of en bloc versus piecemeal resection need to be carefully balanced. In our experience, the non-polypoid lesions can be very challenging to capture with a snare.

Seeing the edge of lesions once resection has started can be especially challenging in colitis. Although marking is not usually used even for ESD in the lower GI tract, lesions in colitis have some similarities in their subtle appearance to early gastric cancer where marking prior to resection is routine. Endoscopists may therefore choose to use the snare tip to mark the edges of the lesion with cautery “dots” prior to resection to ensure all dysplastic mucosa is resected (Fig. 20.1d).

Lifting

Lifting or the failure of lifting of lesions in colitis is one of the major obstacles to safe and comprehensive resection. This leads to problems with lesion assessment for invasion as outlined previously, but more importantly means that the lesion cannot be safely lifted away from the underlying muscularis propria to allow a safe plane for the snare or endoscopic knife to traverse. Scarring of the submucosa leads to difficulty in finding the submucosal plane, a failure to lift, a “diffuse” lift where fluid tracks laterally rather than resulting in focal elevation, and a rapid loss of any lift achieved. Techniques to counter these problem include the use of dynamic injection technique [26], the use of thinner bore injection needles, 25 gauge rather than 21G or 23G, to help find the submucosal plane, and the use of more viscous and longer lasting injection solutions including colloids—e.g., succinylated gelatine (Braun Medical, Bethlehem PA, USA)—for which there is some evidence of improved performance at EMR in non-colitic colons [27], or sodium hyaluronate, which has been popularized in ESD and provides a very long-lasting lift. Other viscous solutions—e.g., hypromellose or glycerol—might also be considered [28]. Nevertheless, even with the use of these technique and injectants, the submucosal lift can be quite limited. All such solutions are currently not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Snares

Standard snares can be used for EMR in colitis; however, as alluded to previously, scarred, flat lesions with poor lift can be very difficult to engage into the snare. Furthermore, if a large piece is successfully engaged there is a risk that the scarring will pull up an area of underlying muscle, leading to damage to the muscularis propria “target sign” or a full thickness perforation [29]. Perforations can be especially difficult to close in scarred mucosa. In order to improve snare grip, braided or spiral snares may be used, which have an additional spiral wire around the main snare cable to improve gripping (Spiral snare 20 mm, SnareMaster, Olympus, Tokyo). An alternative is the flat band or “ribbon” snare (Flat ribbon snare 22 mm, Resection Master, Medwork, Höchstadt, Germany). This comprises a flat band of metal to make the snare loop with the edge of the band orientated vertically to the mucosa. This snare cuts into and grips the mucosa more effectively than standard braided snares, but seems to have less hemostatic capacity. An alternative is to use a smaller braided snare to resect small pieces at a time, reducing the risk that too much mucosa is gathered with associated muscle as one might do for a scarred lesion in non-colitic colons. A final option is the use of a double channel endoscope using a grasper to pull mucosa into a snare, which is in the other channel. Although this technique guarantees the ability to grip mucosa, the risk of perforation is significantly magnified, and experience and extreme care are needed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree