Ejaculatory duct obstruction presents with infertility, pain, or hematospermia. Partial or functional forms of ejaculatory duct obstruction can be difficult to diagnose. Transrectal ultrasound has replaced formal vasography as the first-line diagnostic test but is not specific. Adjunctive procedures such as seminal vesicle aspiration, seminal vesiculography, and chromotubation further delineate the diagnosis. Using an evidence-based approach, this article reviews how best to approach the diagnosis and treatment of ejaculatory duct obstruction.

First described by Farley and Barnes in 1973, ejaculatory duct obstruction (EDO) underlies 1% to 5% of male infertility . Although the diagnosis of EDO can be complex, treatment is well established and can be very effective . In the past decade, transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) has replaced vasography as the mainstay of diagnosis. Although originally described in azoospermic men harboring complete blockage, it now is clear that EDO may present in several ways, including azoospermia and oligoasthenospermia. Excellent information provided by TRUS has improved the ability of the urologist to diagnose EDO.

Because a significant proportion of men who undergo treatment for EDO do not respond, the limitations of a TRUS-based diagnosis also have become apparent. This experience has led to the development of further diagnostic procedures to confirm EDO in select patients. Several adjunctive techniques now have been described, including seminal vesicle aspiration, seminal vesicle chromotubation, and seminal vesiculography. This article reviews these diagnostic techniques and their limitations and proposes an evidence-based, algorithmic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of this underdetected clinical condition.

Ejaculatory duct anatomy and physiology

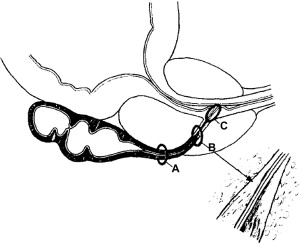

Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the ejaculatory ducts is important for the diagnosis and management of EDO. Anatomically, the ejaculatory ducts are paired, collagenous, tubular structures that commence at the junction of the vas deferens and seminal vesicle, course through the prostate, and open into the prostatic urethra at the verumontanum ( Fig. 1 ). The duct has three regions: a proximal, extraprostatic portion, a middle intraprostatic segment, and a short distal segment within the verumontanum near the urethra (see Fig. 1 ) . Contrary to popular belief, there is no valvelike, muscular “sphincter” at the ejaculatory duct orifice, because the duct sheds its muscular layer in the middle, intraprostatic segment . Instead, ejaculatory continence is maintained and urinary reflux prevented by the acute angle of duct insertion into the prostatic urethra.

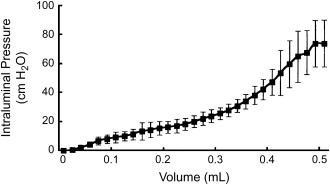

The physiology of the ejaculatory duct complex also is well understood. Animal model studies indicate that a relationship exists between the seminal vesicle and ejaculatory duct that is quite similar to that of the bladder and urethra . Specifically, the compliance and contractile properties of the smooth, muscle-lined, viscous organ that is the seminal vesicle are very similar to those described for the bladder ( Fig. 2 ) . Just as bladder outlet obstruction can result from prostatic or other blockage, so too can physical blockage of the ejaculatory ducts cause EDO. By the same reasoning, “functional” or neurologic dysfunction of the seminal vesicle probably exists that is similar to voiding dysfunction caused by bladder myopathy. Like the neurogenic bladder, this pathologic state could result in functional EDO .

Given the physiologic similarity between the organs of the ejaculatory duct complex and those of the urinary tract, several implications become apparent. “Static” anatomic imaging with TRUS or MRI may be unable to distinguish between functional and physical EDO. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that TRUS alone leads to a false-positive diagnosis of EDO, defined by lack of clinical benefit, in 50% of clinical cases Thus, although it has simplified the diagnosis, TRUS is sensitive but not specific for EDO and may be even less informative in partial or functional forms of the disease. The clinical implications are (1) the evaluation of EDO should include a review of the use of medications and medical conditions that might predispose the patient to seminal vesicle dysfunction, and (2) “static” anatomic imaging such as TRUS may not be sufficient to distinguish among all the forms of EDO that can exist.

Definition of ejaculatory duct obstruction

Based on the current understanding of the anatomy and physiology, it is clear that EDO takes several forms ( Table 1 ). Low-volume azoospermia defines complete or classic EDO and represents the physical blockage of both ejaculatory ducts. Unilateral complete or bilateral partial physical obstruction results in incomplete or “partial” EDO. Both these types of EDO are associated with one or more symptoms of low ejaculate volume, postejaculatory pain, or hematospermia. Partial EDO is uniquely associated with oligoasthenospermia. Currently, the diagnosis of functional EDO is one of exclusion and is made when anatomic evidence of obstruction is ruled out.

| Parameter | Incomplete or partial obstruction | Complete obstruction | Functional obstruction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculate volume | Low or low-normal | Low | Low |

| Sperm count | Low | Absent | Absent or low |

| Sperm motility | Low | Absent | Absent or low |

| Ejaculate fructose | Absent or low | Absent | Absent or low |

Definition of ejaculatory duct obstruction

Based on the current understanding of the anatomy and physiology, it is clear that EDO takes several forms ( Table 1 ). Low-volume azoospermia defines complete or classic EDO and represents the physical blockage of both ejaculatory ducts. Unilateral complete or bilateral partial physical obstruction results in incomplete or “partial” EDO. Both these types of EDO are associated with one or more symptoms of low ejaculate volume, postejaculatory pain, or hematospermia. Partial EDO is uniquely associated with oligoasthenospermia. Currently, the diagnosis of functional EDO is one of exclusion and is made when anatomic evidence of obstruction is ruled out.

| Parameter | Incomplete or partial obstruction | Complete obstruction | Functional obstruction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculate volume | Low or low-normal | Low | Low |

| Sperm count | Low | Absent | Absent or low |

| Sperm motility | Low | Absent | Absent or low |

| Ejaculate fructose | Absent or low | Absent | Absent or low |

Diagnosis of ejaculatory duct obstruction

The causes of EDO are divided into congenital and acquired disorders ( Fig. 3 ). It can result from seminal vesicle calculi, Müllerian duct (utricular) or Wolffian duct (diverticular) cysts, postsurgical or postinflammatory scar tissue, calcification near the verumontanum, or congenital atresia of the ducts . The issue of prostatic cysts as a cause of EDO is interesting, because they are found in the prostate relatively commonly, but most are unlikely to cause obstruction. The incidence of prostatic cysts involving the ejaculatory ducts in infertile men has been reported to be as high as 17%, compared with a screening population in which the prevalence was 5% . In cases of congenital blockage, the urologist should consider a genetic evaluation for cystic fibrosis gene mutations, because men who have idiopathic obstruction have a high prevalence (50%) of cystic fibrosis gene mutations .

Clinical presentation

Clinically, EDO classically presents as hematospermia, painful ejaculation , or infertility (see Fig. 3 ). Persistent or recurrent hematospermia indicates the need for TRUS, which may delineate abnormalities, including dilated seminal vesicles, ejaculatory duct cysts, calculi, absence of the vas, and intraprostatic Müllerian duct remnants . Evaluation of hematospermia by TRUS reveals a malignant source in fewer than 4% of cases, however . A prior urinary tract infection, epididymitis, perineal trauma, orchalgia, and perineal pain also may indicate the possibility of EDO. It is important to discontinue medications that may impair ejaculation ( Box 1 ). Although unusual, a digital rectal examination demonstrating enlarged, palpable seminal vesicles may suggest the diagnosis of EDO. Although no pathognomonic findings exist on seminal evaluation for EDO, azoospermia in a centrifuged semen sample, associated with a low ejaculate volume (<2.0 mL), a pH below 7.2, and absence of fructose in the seminal fluid suggest EDO (see Table 1 ). The finding of low ejaculate volume in association with impaired sperm concentration and motility and a positive clinical history also may warrant further evaluation for EDO (partial or functional). Part of the reason that this condition probably is underdiagnosed is because of its rarity, subtle presentation, and the concomitantly low index of suspicion held by clinicians.