DIVERTICULOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Radiographic or endoscopic demonstration of diverticula.

Normal vital signs and laboratory evaluation.

Absence of complications (diverticulitis, diverticular hemorrhage).

Diverticula are acquired herniations of the colonic mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis propria. They occur most commonly in the sigmoid colon and can vary in size and number, although typically they are between 5 and 10 mm in diameter. Diverticulosis refers to the presence of diverticula in an individual who is asymptomatic, whereas diverticular disease refers to the presence of diverticula associated with symptoms, which occurs in 20% of individuals with diverticula.

Diverticular disease is the most common structural abnormality of the colon. It is estimated to affect 2.5 million individuals in the United States. In terms of health care expenditures (both direct and indirect costs), it is the fifth most important gastrointestinal disease in Western countries, representing total annual expenditures in the United States of over $3 billion. It accounts for approximately 3.2 million office visits and for more than 815,000 hospital admissions annually in the United States, with a mortality rate of 2.5 per 100,000 persons per year.

Although diverticula were described as early as 1700, diverticulosis was uncommon until the 20th century. Currently, it is estimated that diverticulosis affects less than 5% of people at age 40, 30% of people by age 60, and 50–65% of people by age 80. An exception to this is in vegetarians, in whom the prevalence of diverticulosis is much lower, presumably due to diets that are higher in fiber. Men and women are affected equally. The prevalence and distribution of diverticula vary throughout the world. Whereas diverticula are common and predominantly left-sided in Western countries (95% involve the sigmoid colon), in urbanized areas of Asia, such as Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, the prevalence is only 20% and the diverticula are predominantly right-sided, even among those who have adopted a Western-style, low-fiber diet.

Segmentation within the colon is thought to play an important role in the development of diverticula. Segmentation refers to the process by which a short segment of the circular muscle of the colon contracts in a nonpropulsive manner. This produces a closed segment of colon with increased intraluminal pressure, and likely serves to increase water and electrolyte absorption from the colon. These elevated intraluminal pressures may ultimately result in herniation of the mucosa and submucosa at sites of weakness (namely, where the vasa recta penetrates the muscularis propria between the taeniae coli), resulting in the formation of diverticula. Diverticula are not seen in the rectum because the taeniae coalesce at the rectum to form the circumferential longitudinal muscle layer.

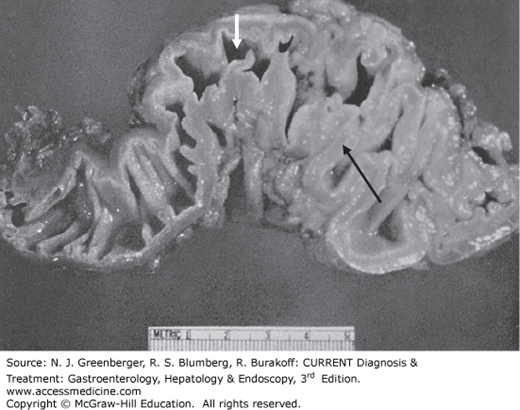

The law of Laplace (transmural pressure gradient equals the wall tension divided by the radius, ΔP = T/r) may help to explain why diverticula are so common in the sigmoid colon. Compared with the remainder of the colon, the sigmoid has a smaller radius. Because the transmural pressure gradient is inversely proportional to the bowel radius, it will be highest at the level of the sigmoid, potentially favoring the formation of diverticula in this region. Additionally, myochosis (thickening of the circular muscle layer, shortening of the taeniae coli, and narrowing of the lumen, Figure 21–1) is seen in most patients with sigmoid diverticula. These changes result from increased deposition of collagen and elastin within the taeniae, and not from hypertrophy or hyperplasia of the bowel wall. In addition to increasing intraluminal pressure by narrowing the lumen, these changes may also decrease the resistance of the colon wall (see below).

Alterations in myoelectrical activity may also contribute to the development of diverticulosis. The interstitial cells of Cajal are thought to be responsible for the generation of slow waves. Extracellular electrodes show that these slow waves correspond to muscle contractions within the colon. Some studies have shown increased slow-wave activity in patients with diverticulosis, which could result in increased segmental contractions. However, one study found that there were significantly reduced numbers of interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with diverticulosis, possibly leading to delayed transit.

As individuals age, the tensile strength of the collagen and muscle fibers of the colonic wall decreases due to increased cross-linking of abnormal collagen fibers and deposition of elastin in all layers of the colonic wall. The colonic wall may be weakened by the breakdown and damage of mature collagen, as well as by the synthesis of immature collagen. This may also contribute to the creation of more distensible muscle fibers. The importance of structural changes in the colonic wall is suggested by the early formation of diverticula in patients with connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and polycystic kidney disease.

Collagen fibers vary in conformation throughout the colon. With increasing age, the collagen fibrils in the left colon become smaller and more tightly packed compared with those in the right, changes that are accentuated in diverticular disease. This may explain why colonic compliance is lower in the sigmoid colon and descending colon compared with the transverse and ascending colon, and may also explain why diverticular disease is more common in the left colon.

Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling is mediated in part by matrix metalloproteinases. Activation of matrix metalloproteinases results in the degradation of the extracellular matrix, including collagens, noncollagenous glycoproteins, and proteoglycans. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases serve as local regulators by blocking the effects of matrix metalloproteinases. Patients with diverticular disease have been shown to have an increase in collagen synthesis, an increase in tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, and a decrease in the expression of a matrix metalloproteinase subtype that is responsible for the degradation of collagen. These changes may contribute to the changes in the structure of the colonic wall seen in patients with diverticulosis.

Patients who have symptoms from uncomplicated diverticular disease resemble patients with irritable bowel syndrome. In both groups, visceral hypersensitivity has been demonstrated in response to rectosigmoid distention. Patients with asymptomatic diverticulosis, however, do not demonstrate increased pain perception with rectal distention. The visceral hypersensitivity seen in patients with symptomatic diverticular disease is not limited to areas of the sigmoid with diverticula and is not associated with altered colonic wall compliance. This suggests that there is a generalized state of visceral hypersensitivity in symptomatic diverticular disease that is similar to that seen in irritable bowel syndrome.

Patients with diverticulosis may exhibit low-grade colonic inflammation that resembles inflammatory bowel disease histologically, a condition known as segmental colitis. Segmental colitis is characterized by a chronic inflammatory process that is localized to the portion of the colon with diverticula, sparing the rectum and right colon.

While the exact prevalence is not known, retrospective studies have found segmental colitis in 0.25–1.5% of patients undergoing colonoscopy. In patients with diverticular disease, the prevalence is 1.2–11%.

The pathophysiology of segmental colitis is unknown. Multiple theories have been put forth, including that it is an atypical form of inflammatory bowel disease, that it is the result of mucosal redundancy and prolapsed mucosa, and that it results from changes in bacterial floral and bacterial enzyme activity due to fecal stasis within diverticula. There is evidence to support the theory that segmental colitis is a form of inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with segmental colitis have higher levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) that controls with irritable bowel syndrome; segmental colitis often behaves similarly to ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease; it often has endoscopic and histologic appearances that are similar to inflammatory bowel disease, and in one case report, it responded to treatment with infliximab.

Fiber in the diet leads to increased stool bulk and decreased colonic transit times and thus may play a role in preventing the development of diverticulosis. Individuals from countries with high-fiber diets tend to have larger diameter colons, compared with those from countries with low-fiber intake. Having a larger colonic diameter may impair the segmental contractions of the colon that lead to higher intraluminal pressures.

The role of fiber in the development of diverticulosis was first suggested by epidemiologic evidence. Diverticula rarely develop in rural Asia or Africa (prevalence of <0.2%), where diets are high in fiber. However, in areas that have developed economically and have adopted Western dietary habits, diverticula become more prevalent. In addition, populations that have moved from rural to urban environments show an increased prevalence of diverticulosis. However, more recent studies have called into question the role of fiber in the development of diverticulosis. In a study of patients undergoing colonoscopy (539 found to have diverticulosis and 1569 without diverticulosis), dietary fiber intake was assessed within 3 months of the examination. There was no association with dietary fiber intake and diverticulosis. However, whether the fiber intake assessed around the time of colonoscopy was representative of the patients’ prior fiber intake (during the period when diverticula would have been forming) could not be ascertained.

The majority of patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic, with only 20% developing symptoms over their life span. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom, and is usually localized in the left lower quadrant. It is important to emphasize that left lower quadrant pain may be the result of myochosis (thickening of the circular muscle layer, shortening of the taeniae coli, and narrowing of the lumen often seen in patients with diverticular disease). In patients with right-sided diverticula, the pain can be felt in the right lower quadrant. The pain may worsen after eating and in some is relieved with the passage of stool or flatus. Patients may also complain of nausea, cramping, irregular bowel movements (intermittent diarrhea or constipation), bloating, and flatulence. Patients with segmental colitis may present with chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, or rectal bleeding.

Patients do not demonstrate abnormal vital signs, such as tachycardia or fever, in uncomplicated diverticulosis. With palpation of the left lower quadrant, mild tenderness and voluntary guarding may be present.

In uncomplicated diverticulosis, laboratory values, including the hematocrit, hemoglobin, and white blood cell count, are normal, and testing of the stool for occult blood is negative.

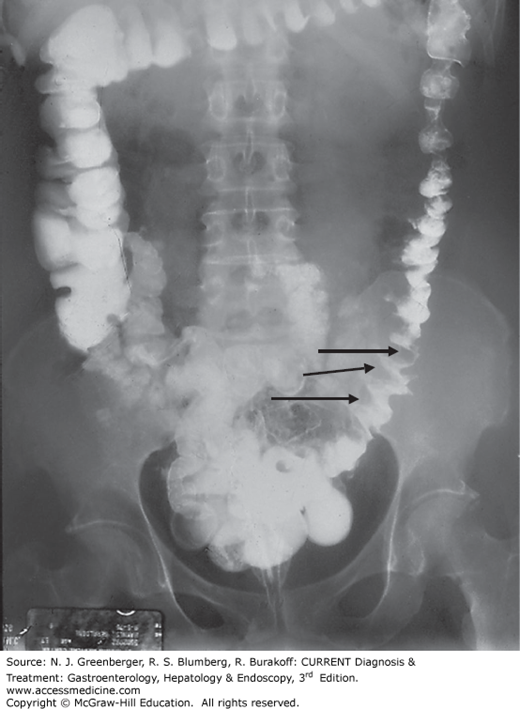

A double-contrast barium enema will demonstrate the presence, localization, and number of diverticula (Figure 21–2). If segmental spasm is present, a transient saw-tooth pattern may be seen. In uncomplicated diverticulosis, there should be no extravasation of contrast, nor should there be evidence of fistulae, strictures, or persistent spasm, all of which suggest diverticulitis. Diverticulosis can also be seen on abdominal computed tomography (CT) with oral or rectal contrast.

In patients with myochosis, a plain abdominal x-ray may show scalloping in the left colon due to muscle hypertrophy (Figures 21–1 and 21–3).

Diverticulosis is frequently discovered during colonoscopy as an incidental finding (Plate 24). Additionally, because disorders such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and ischemic colitis are included in the differential diagnosis for patients with abdominal pain related to diverticulosis, colonoscopy is the preferred diagnostic study. Colonoscopy, however, can be difficult to perform in patients with diverticulosis due to narrowing of the colonic lumen and possible colonic fixation from prior episodes of diverticulitis resulting in inflammation and pericolic fibrosis. Colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated in patients in whom acute diverticulitis is suspected, due to an increased risk of colonic perforation.

In patients with segmental colitis, endoscopy reveals inflammation of the interdiverticular mucosa, characterized by erythema, granularity, and friability. The involvement may be diffuse or patchy. The inflammation is only seen in areas with diverticula and spares the rectum. The rectal sparing is particularly important when attempting to differentiate segmental colitis from ulcerative colitis, since the two entities can appear very similar both endoscopically and histologically. Histologic findings include nonspecific mucosal inflammation, crypt abscesses, a mononuclear cell infiltrate in the lamina propria, and occasional submucosal inflammation.

The nonspecific symptoms of uncomplicated diverticulosis can mimic many other conditions, and differentiation can be difficult. Many of the signs and symptoms of symptomatic diverticulosis are also seen in irritable bowel syndrome. The fact that both disorders are common, and can coexist, makes differentiation even more difficult. Irritable bowel syndrome frequently causes diffuse abdominal pain; thus, pain localized to the left lower quadrant in the setting of demonstrated diverticula supports a diagnosis of uncomplicated diverticulosis.

Mild diverticulitis can manifest similarly and is not ruled out by the absence of a fever, elevated white blood cell count, or other signs of infection. Other pelvic infections, such as appendicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease, can also mimic diverticulosis. Other causes of lower abdominal pain that need to be considered are infectious colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, colorectal cancer, and endometriosis.

Diverticulosis can be complicated by acute diverticulitis, which results from the perforation of a diverticulum, as well as by hemorrhage, which occurs when the arteriole associated with the diverticulum erodes.

Most patients with diverticulosis do not require any specific treatment, and there are no medical treatments that will lead to the regression of diverticula, once present. The treatment of patients with recurrent uncomplicated diverticular disease focuses on relieving symptoms. Therapies used to treat uncomplicated diverticular disease include fiber-rich diets, nonabsorbable antibiotics, mesalazine, probiotics, and prebiotics. Contrary to popular teaching, there is no strong evidence that seeds, nuts, or popcorn lead to an increase in the frequency of complications from diverticulosis. Patients with myochosis may get symptom relief with the addition of a fiber supplement.

Treatment approaches for segmental colitis have only been studied in small groups of patients or presented as case reports. Treatments include oral and topical mesalazine, topical steroids, high-fiber diets, antibiotics, oral steroids, probiotics, and infliximab. Patients with severe disease may require segmental or total colectomy. Patients with mild to moderate disease often respond well to medical therapy (most often with a 5-aminosalicylate), while patients with more severe disease may require topical and/or oral steroids.

Fiber is slowly fermented by gut microflora, resulting in the production of short-chain fatty acids and gas. This in turn results in shortened gut transit time, which reduces intracolonic pressure and helps with constipation. The recommended daily fiber intake for adults is 20–35 g/day, and fiber supplements are available to help meet this requirement. Supplements contain either soluble fiber (psyllium, ispaghula, calcium polycarbophil) or insoluble fiber (corn fiber, wheat bran). Soluble fiber is more readily fermented by gut microflora, whereas insoluble fiber undergoes minimal fermentation, and likely exerts its effects by increasing stool mass and thus increasing the luminal diameter, which in turn decreases the transmural pressure gradient. (Recall that, according to the law of Laplace, ΔP = T/r.) Studies looking at the effect of high-fiber diets on symptoms from uncomplicated diverticular disease, however, have not been conclusive, with some studies showing a benefit, while others do not. Despite this, increasing dietary fiber, often with fiber supplements, is currently the mainstay of treating uncomplicated diverticular disease.

Rifaximin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that acts by binding to the β-subunit of bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Eighty to 90% of rifaximin remains within the gut. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, rifaximin has been shown in a few studies to improve the symptoms of uncomplicated diverticular disease. Symptom improvement may be due to the ability of rifaximin to influence the metabolic activity of gut flora that degrade dietary fiber and produce gas. The drug may also influence the gut flora responsible for chronic, low-grade mucosal inflammation. Two studies in which patients were randomized either to rifaximin plus a fiber supplement or to placebo plus a fiber supplement for 1 year demonstrated symptom improvement in those who received rifaximin. In one study, the number of patients reporting no or only mild symptoms at the end of the study was 69% in the group that received rifaximin and 39% in the group that received placebo. Another study showed that in patients treated over the course of 10 years with rifaximin, 5% had a relapse of symptoms, with 1% developing complications.

Mesalazine is an anti-inflammatory drug that acts topically on the gut mucosa and is typically used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Because some of the symptoms of diverticular disease may be related to chronic mucosal inflammation, mesalazine may have a role in the treatment of patients with symptoms related to diverticular disease. In a 2004 study, 90 patients were treated with rifaximin plus mesalazine (800 mg three times daily) for 10 days and then received mesalazine alone (800 mg twice daily) for another 8 weeks. At the end of the study, 81% of patients reported being asymptomatic. From this, the investigators concluded that mesalazine may help to maintain clinical remission.

Probiotics contain microorganisms with beneficial properties, and the goal in using them is to alter the gut’s microflora to reestablish the normal bacterial flora. Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli are used most frequently. Some preparations also contain other bacteria and nonbacterial organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces boulardii. In diverticular disease, the normal bacterial flora may be altered by slowed colonic transit and stool stasis, so it is theorized that reestablishing normal gut flora may lead to symptomatic improvement. In a study of patients with colonic stenosis following an episode of diverticulitis, the combination of rifaximin and lactobacilli for 12 months was effective in preventing symptom recurrence and complications. In a second study, a small group of patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease were given an intestinal antimicrobial agent and an absorbent. That was followed by administration of a nonpathogenic E coli strain for a mean period of 5 weeks. These patients showed improvement in all abdominal symptoms.

Prebiotics are substances that promote the growth and metabolic activity of beneficial bacteria, especially Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. Prebiotics are frequently indigestible complex carbohydrates. Bacteria ferment these substances, leading to a more acidic luminal environment, which suppresses the growth of harmful bacteria. Substances that have been shown to promote the growth of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli include psyllium fiber, lactulose, fructose, oligosaccharides, germinated barley extracts, and inulin.

Twenty percent of patients with diverticula will develop symptoms of uncomplicated diverticular disease, while 10–25% of patients with diverticulosis will go on to develop a complication (75% of whom will have had no preceding symptoms). Fortunately, most episodes of diverticulitis and diverticular hemorrhage are self-limited and can be managed medically. An additional small subset of patients will develop severe pain and colonic dysmotility. Although not life threatening, the symptoms can be debilitating.

[PubMed: 23891924]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree