Diverticular Disease

R. John Nicholls

Diet cures more than the lancet.

—SPANISH PROVERB

Man shall not live by bread alone.

—MATTHEW 4:4; LUKE 4:4

Diverticulum (a; pl); Latin = a wayside inn, presumably of ill repute

Diverticular disease is a very common condition, and in an aging population it will become even more so. Most patients with diverticula have no symptoms, but about 20% have complaints and of these a minority develops a complication. These can be divided into septic or nonseptic, acute or chronic. Acute inflammation of a diverticulum results in the condition of acute diverticulitis. This can lead to a local or to a free perforation. Most patients with acute diverticular disease are managed medically but those with local abscess formation or free perforation may require intervention, either drainage of a localized abscess or surgery for peritonitis. Those who respond to medical measures have been usually often advised to consider a subsequent elective surgical resection of the diseased segment after the inflammation had settled.

In the last 5 years, important changes in practice have taken place. First, it is apparent from follow-up studies that the possibility of a recurrent acute attack (thought to have been 10% to 25% over the following few years) is lower than previously believed. This has led to a revision in the guidelines regarding further surgery. Those published by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) in 2006 are currently in the process of revision.242 The view of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland expressed in a position statement in 2011 is that elective resection should be recommended based on the particular circumstances of the patient.96 Thus, the number of prophylactic resections is likely to diminish. The second development is a consequence of the development of laparoscopic surgery whereby peritoneal lavage may now be favored over open surgery in patients with purulent peritonitis (Hinchey stage III).129,208,301,311 At the present time, it is not known whether such patients should be advised to have a subsequent elective resection.

Chronic diverticular disease can take the form of fistulization from a diverticulum into an adjacent organ or of stricture formation that may cause obstruction, or it can simply be associated with symptoms of lower abdominal pain and a tendency to constipation. The indication for surgery in patients with a fistula or symptomatic stricture is usually straightforward. It is much more difficult to decide whether surgery will benefit patients with symptomatic noncomplicated disease. This is due to the overlapping of symptoms with that of an irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

▶ HISTORY AND INCIDENCE

Diverticular disease was a rare condition prior to the beginning of the 20th century. It had been described by Littre in 1700 (see Biography, Chapter 24),92 but further reports were not seen until the 19th century when Cruveilhier (see Biography, Chapter 20) included the disease in his beautifully illustrated book on pathology published in 1849 shortly before the introduction of photography.71 Painter and Burkitt described further contributions by Rokitansky, Cripps, and Virchow but until the 20th century, the condition was regarded as a surgical curiosity.222 The term peridiverticulitis was introduced by Graser in 1899.111 He suggested that the diverticula were due to herniation through the bowel wall. Beer considered that the inflammation was the result of obstruction of the orifices of the diverticula by feces.31 In reports by Telling and Gruner, the complications of acute diverticular disease were described including abscess and fistula formation.303,304

The disease had thus become progressively more pervasive in the 20th century and is virtually epidemic in Western countries today.275 A person’s risk for the development of diverticular disease by age 60 in the United States approximates 50%. By the age of 80 years, virtually all Americans have the condition. Yet, not more than 20% of persons with colonic diverticula have symptoms, and only a few of these ever require surgery.229 Of the 10% to 15% of individuals with diverticula who go on to develop diverticulitis, 75% are uncomplicated in the sense of not having features of perforation, localized or general. However, 25% have an abscess, obstruction, perforation, or fistula. Perforation is uncommon, occurring at about the rate of 4 per 100,000 per year, with women having about half the incidence of men.275

In the United States, diverticular disease accounts for approximately 450,000 annual hospitalizations, 2 million office visits, and 112,000 disability cases, and it claims approximately 3,000 lives per year.162 Diverticulosis of the colon is most common in the sigmoid in the United States, whereas the location is primarily right-sided in Asian populations. In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the number of hospital admissions for diverticular disease (see next).

▶ CLASSIFICATION

Diverticular disease is defined by the presence of diverticula. Most patients with diverticular disease are asymptomatic and are referred to as having diverticulosis or asymptomatic diverticular disease. About 20% complain of symptoms and are said to have symptomatic diverticular disease. A proportion of these develops a complication and are said to have complicated diverticular disease. Complications result from local sepsis causing acute diverticulitis; local contained perforation (paracolic abscess) or free perforation causing purulent or fecal peritonitis; or from chronic inflammation causing fistula formation, stricture formation, or secondary hemorrhage (Table 27-1).

In the report of the working party appointed by the ASCRS entitled “Practice Parameters for Sigmoid Diverticulitis,” Rafferty and colleagues refer to diverticulitis without any abscess or other septic complication as “uncomplicated diverticulitis” and use the term “complicated diverticulitis” to include patients with abscess formation or perforation.242 The reader needs to be aware of minor differences in terminology by careful reading of the text in question.

TABLE 27-1 Classification of Diverticular Disease | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

▶ EPIDEMIOLOGY

Diverticular disease is an important source of morbidity and mortality. As previously mentioned, there is evidence that it is becoming more prevalent. In the United States, the National Hospital Discharge Survey in the year 2004, it was demonstrated that diverticular disease was responsible for 312,000 admissions and 1.5 million days of inpatient care per year at an annual cost of $2.6 billion.162,263 In a recent article, Etzioni and colleagues, using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 1998 to 2005, showed a 26% increase in admissions for acute diverticulitis from 1998 (121,000) to 2005 (152,000).86 They showed a reduction in age from 64.8 to 61.8 years during this period and also demonstrated that there was an increase in admissions in the age groups 18 to 44 and 45 to 64 years, whereas the figure for 65 to 74 years remained stable and that for older than 75 years fell. Mäkelä and colleagues have estimated the annual incidence of perforated diverticulitis in Finland to have increased from 2.4/100,000 per year to 3.8/100,000 per year from 1986 to 2000.181 In England between 1989/1990 and 1999/2000, information from the Department of Health Hospital Episode Statistics showed that from 1989/1990 to 1999/2000 there had been an increase in admissions by 16% for males (20.1 to 23.2/100,000 population) and by 12% for females (28.6 to 31.9/100,000 population).150 The proportions of admissions undergoing surgery also increased for males, from 22.9% to 24.1% (16%), and for females, 19.7% to 22.3% (14%). In a recent study using the Scottish national linkage database between 1996 and 2010, the number of hospital admissions increased from 5,284 to 10,935. Most of these were for endoscopy, but 26% were attributed to admissions for treatment of acute disease.25

It is difficult to measure the prevalence because most patients are asymptomatic. Most of the information comes from autopsy and barium enema series with rates varying between 2% and 10%.222 The prevalence of diverticula increases with age, from less than 10% in those younger than age 40 years to 50% to 66% in patients older than age 80 years, with no apparent sex difference.222,228

Burkitt was the initiator of the theory that diverticular disease is a disease of Western industrialized societies such as in the United States, Europe, and Australia. The hypothesis was supported by the low prevalence of the condition in East Africans. Even within a given country the incidence can vary between ethnic groups, such as in Singapore where the frequency among the Chinese and European populations has been reported to be 0.14 and 5.41 cases per million

population. There is evidence that in low-risk communities, the incidence is rising. For example, its prevalence in Singapore was reported to be 19% by Lee in 1986 and also in Africa.170,213,330 With economic development, affluence, and westernization of diet, an increased incidence of diverticular disease has been noted among native Africans.312 Other studies have demonstrated an increased incidence in immigrants to Western countries from less developed nations in comparison with persons remaining in the country of origin. Complicated diverticulitis has increased in Finland by 50% in the past two decades.181

population. There is evidence that in low-risk communities, the incidence is rising. For example, its prevalence in Singapore was reported to be 19% by Lee in 1986 and also in Africa.170,213,330 With economic development, affluence, and westernization of diet, an increased incidence of diverticular disease has been noted among native Africans.312 Other studies have demonstrated an increased incidence in immigrants to Western countries from less developed nations in comparison with persons remaining in the country of origin. Complicated diverticulitis has increased in Finland by 50% in the past two decades.181

DENIS PARSONS BURKITT (1911-1993)

|

Denis Burkitt was born February 28, 1911, in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, the son of an engineer. Without any particular interest in medicine, he followed in his father’s footsteps to engineering school at Dublin University. An indifferent student, he learned of a letter the don had written to his father in which he expressed doubt as to Denis’s ability to obtain a university degree and warned about the risk of forfeiting the £10 enrollment fee. It is therefore ironic that many years later he received the university’s highest award, an honorary fellowship of Trinity College, Dublin. Interestingly, in light of Burkitt’s subsequent career, the British Colonial Office rejected his offer for service in Africa because he had lost an eye in an accident at the age of 11. He abandoned the course he had initiated, instead seeking and obtaining admission to medical school, an act he attributed to a commitment to the highest ideals and principles of his Christian faith. Burkitt completed medical school at Dublin in 1936, received his fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh in 1938, and his doctorate in 1946. Through the Second World War, he served with the Royal Army Medical Corps, and in 1946 he joined His Majesty’s Colonial Service in Uganda as a government surgeon and lecturer at the Makerere University College Medical School. He became committed to serving less privileged people than himself. The rest is medical history. In 1957, he treated a child with swellings in both maxillae and mandibles, a condition that ultimately came to be known as Burkitt’s lymphoma. This led to the discovery of the cause and to the subsequent identification of the Epstein—Barr virus. His keen sense of observation and knowledge of epidemiology helped him to recognize that the most common diseases of Western civilization were virtually unknown in rural populations of developing countries. Modestly, he stated that were it not for the reputation of his eponymous association with a lymphoma, no one would have listened to his thoughts concerning the epidemiology of colon cancer. Numerous honors came to Burkitt, including the Harrison Prize of the Royal Society of Medicine, the Stewart Prize of the British Medical Association, and the Walker Prize of the Royal College of Surgeons. Honorary degrees and fellowships were awarded to him by numerous universities and organizations throughout the world. The author of six books and more than 300 scientific publications, he actively wrote from his home in Gloucester, England, until the end of his life. When autographing a book, he always penned these thoughts: “Attitudes are more important than abilities; motives are more important than methods; character is more important than cleverness; and stick-to-it-iveness is more important than the starting place.”

Painter and Burkitt are the two individuals most responsible for our current concepts of the etiology and epidemiology of diverticular disease.48,49,219,220 and 221,223 Because the condition was extremely rare in the 19th century and began to be relatively commonly observed in Western countries only after 1920, the authors postulated that a change in the dietary habits in those countries was the incriminating factor. During the years 1870 and 1880, the grist mills for grinding wheat into wholemeal flour were replaced by the much more efficient roller mills. This new process succeeded in crushing the grain so effectively that a very pure white flour was produced. At about the same time, with the advent of effective refrigeration and canning, consumption of refined sugar, fat, and protein increased. Painter and Burkitt stated that the greatest change in our diet in the past 100 years has been a reduction in the amount of cereal fiber consumption to as little as one-tenth of that previously eaten.223 Because of this sudden change within a matter of approximately 40 years, diverticular disease had become epidemic.

Fiber increases stool weight, decreases whole-gut transit time, and lowers colonic intraluminal pressure.24,68 A highfiber diet produces a large, bulky stool that requires less “effort” for the bowel to expel its contents. Bran increases stool weight by virtue of its water-retentive properties. Bowel wall muscular hypertrophy does not occur, and segmentation is much less likely to develop. Burkitt and colleagues compared the transit times and stool weights of various ethnic groups.49,219 They were particularly interested in the low incidence of colorectal disease in rural African natives. Ugandan villagers passed more than 400 g of stool within 35 hours, whereas shore-based United Kingdom naval personnel produced 100 g of constipated stool, with a transit time of approximately 5 days.

Gear and colleagues reported the results of barium enema examination in vegetarians and nonvegetarians.105 The mean intake of dietary fiber was twice as great in the former group. Vegetarians were found to have a 12% incidence of diverticular disease, compared with 33% among nonvegetarians. Others have confirmed the importance of diet in the pathogenesis of diverticulosis.127,183

▶ PATHOGENESIS AND PATHOLOGY

Diverticular disease affects the sigmoid colon in almost all cases. Diverticula may extend proximally to a varying degree and rarely may be present throughout the whole colon. The rectum is not affected. In the East, right-sided diverticular disease is the more common form.209 The bowel wall may be thickened with smooth muscular hypertrophy

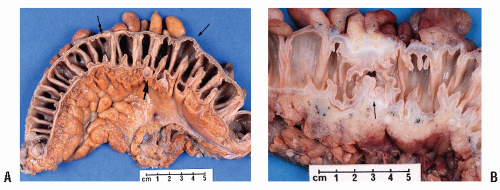

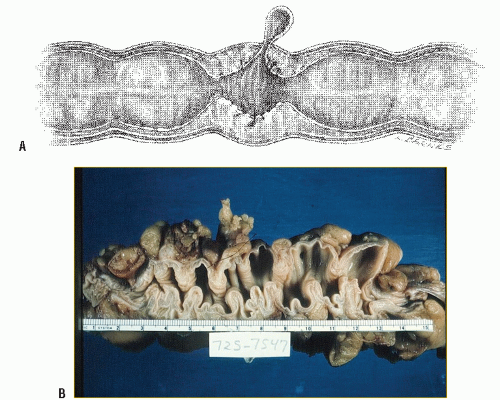

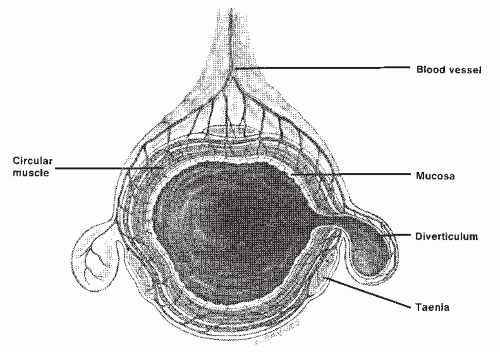

and degeneration when it may be replaced by elastic tissue. In an anatomic study, Slack examined 141 autopsy and 36 surgical resection specimens, including blood vessel injection by latex or barium paste.287 He found that diverticula were consistently located to the points of penetration of the bowel wall by the circumferential branches of the mesenteric artery, which run symmetrically around the colon from the mesenteric to the antimesenteric border on each side. These vessels penetrate the circular muscle of the wall on the mesenteric side of the antimesenteric taenia where they then continue submucosally to anastomose with each other in the antimesenteric area (Figure 27-1). There was no case of a diverticulum emerging through a taenia. A branch of the circumferential artery was seen supplying the mucosa at this point, which may be relevant to the complication of hemorrhage (see Chapter 28).199 In addition, he found that there was hypertrophy of the circular muscle resulting in a foldlike deformity of the lumen. The taeniae were also hypertrophied and the bowel length contracted (Figure 27-2).

and degeneration when it may be replaced by elastic tissue. In an anatomic study, Slack examined 141 autopsy and 36 surgical resection specimens, including blood vessel injection by latex or barium paste.287 He found that diverticula were consistently located to the points of penetration of the bowel wall by the circumferential branches of the mesenteric artery, which run symmetrically around the colon from the mesenteric to the antimesenteric border on each side. These vessels penetrate the circular muscle of the wall on the mesenteric side of the antimesenteric taenia where they then continue submucosally to anastomose with each other in the antimesenteric area (Figure 27-1). There was no case of a diverticulum emerging through a taenia. A branch of the circumferential artery was seen supplying the mucosa at this point, which may be relevant to the complication of hemorrhage (see Chapter 28).199 In addition, he found that there was hypertrophy of the circular muscle resulting in a foldlike deformity of the lumen. The taeniae were also hypertrophied and the bowel length contracted (Figure 27-2).

FIGURE 27-1. Cross section of colon showing areas of weakness through which the diverticula become manifest. |

The diverticula are of the pulsion type and are produced by herniation of mucous membrane through the weak points of entry of the vessels as a result of raised intraluminal pressure (Figure 27-3).

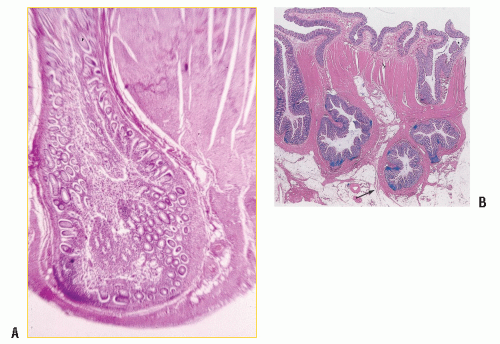

In the absence of complications, particularly inflammation, the lining is entirely normal except for an increase in the size and number of lymphoid follicles.199 The muscle shows thickening but no evidence of cellular hypertrophy or hyperplasia.200 In an autopsy study, Hughes found abnormalities in the arrangement of muscle fibers.136 These were more frequently seen with more extensive diverticular disease (from 30%, with disease limited to the sigmoid, to 86%, with total colonic involvement). Studies have found evidence of abnormal collagen when compared with normal controls.298 Others have also found abnormal collagen.333 Whiteway and Morson showed a marked increase in the elastin content of the bowel wall.335 Antimesenteric diverticula have only a very thin layer of investing tissue, that is, mucous membrane and muscularis mucosae, separating the fecal contents of the bowel from the peritoneal cavity (Figure 27-4).

In the last few years, it has become apparent that there is an association between diverticular disease and that of segmental inflammation, so-called segmental colitis.98,205,320 Study of the physiology of the normal colon by means of

pressure tracings reveals that the principal waveform, that of “segmental contraction,” is shown as a slow change of pressure, waxing, and waning during about 30 seconds.62 Complete quiescence may normally be present for several hours. Usually, the waves are not transmitted to adjacent areas of the colon, but occasionally the transport of material over a considerable distance does occur, during a so-called mass contraction.62 Radiologically, this is seen as a loss of haustration succeeded by movement of the contents through a number of centimeters. Motor studies in patients with diverticular disease reveal an exaggerated response to pharmacologic stimuli, increased intraluminal pressure, and faster

frequency waves and rapid contractions (more than five per minute).62

pressure tracings reveals that the principal waveform, that of “segmental contraction,” is shown as a slow change of pressure, waxing, and waning during about 30 seconds.62 Complete quiescence may normally be present for several hours. Usually, the waves are not transmitted to adjacent areas of the colon, but occasionally the transport of material over a considerable distance does occur, during a so-called mass contraction.62 Radiologically, this is seen as a loss of haustration succeeded by movement of the contents through a number of centimeters. Motor studies in patients with diverticular disease reveal an exaggerated response to pharmacologic stimuli, increased intraluminal pressure, and faster

frequency waves and rapid contractions (more than five per minute).62

FIGURE 27-4. A,B: Diverticulum demonstrating only mucous membrane, muscularis mucosae, and peritoneum separating the lumen from the peritoneal cavity (hematoxylin and eosin). |

Pressure measurements in the sigmoid colon have demonstrated a higher motility index or higher intraluminal pressure in patients with symptoms compared with those who harbor asymptomatic diverticular disease.24,67,80,82 A correlation between low abdominal colicky pain and raised intraluminal pressure following neostigmine was found in patients with diverticular disease compared to those without disease.332 Bassotti and colleagues performed 24-hour manometry measurements in 10 patients with diverticular disease and in 16 controls.29 They found increased motility and increased forceful propulsive activity in the former group.

The points of penetration by the blood vessels create weaknesses in the muscle wall. Raised intraluminal pressure occurring during segmentation movements then results in the formation of diverticula.24,221 When contraction occurs in a segment that is relatively narrowed, considerable intraluminal pressure develops, causing the colon to hypertrophy. The pressure is related to the narrowness or spasticity of the involved segment. According to the law of Laplace, the tension in the wall of an elastic hollow spheroid is proportional to its radius multiplied by the pressure within. This implies that the intraluminal pressure is greater when the lumen is narrowed and explains the increased likelihood that diverticula will develop in the sigmoid colon, the narrowest segment.

The increased pressure results in herniation of mucosa through the weak parts of the bowel wall (see Figure 27-1).221 The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the tensile strength and elasticity of the colon decline with age; this is most marked on the left side.331 The colonic muscle becomes thickened, and smooth muscle fibers may become replaced by elastic tissue.335

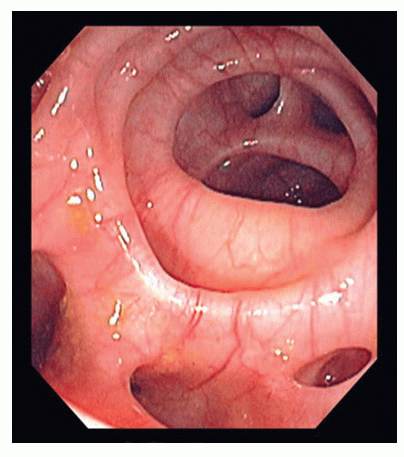

Chronic thickening of the colonic wall with contraction of the musculature explain the symptoms of pain and altered bowel habit. When seen on endoscopy, the orifice of a diverticulum is clear cut and is often accompanied by circular ridges indicative of circular muscle hypertrophy (Figure 27-5). An orifice can become occluded by a fecolith with resultant inflammation. This may lead to a contained or open perforation. In acute diverticulitis, there is evidence of acute inflammation around a diverticulum, with often only one being involved. This is associated with a peritoneal reaction. There may be adhesion to a neighboring structure, such as the bladder in males or the uterus or vagina in females. Local perforation, if contained, will cause abscess formation either in the immediate paracolic region or in the pelvis if

the sigmoid loop is located in the pouch of Douglas. Alternatively, an abscess may erode into a neighboring structure and cause a fistula. A free perforation or perforation of an already formed paracolic abscess will lead to a generalized peritonitis—fecal in the former circumstance and purulent in the latter. The severity of septic complications has been categorized for clinical purposes by Hinchey (see later).129 The bacterial picture is complex and there are no meaningful data on causation in this respect. In a study of 110 specimens from the peritoneal cavity after perforation and of 22 intraabdominal abscesses, Brook and Frazier isolated many species.47 Not surprisingly the majority included Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp., Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Clostridium, and Fusobacterium.

the sigmoid loop is located in the pouch of Douglas. Alternatively, an abscess may erode into a neighboring structure and cause a fistula. A free perforation or perforation of an already formed paracolic abscess will lead to a generalized peritonitis—fecal in the former circumstance and purulent in the latter. The severity of septic complications has been categorized for clinical purposes by Hinchey (see later).129 The bacterial picture is complex and there are no meaningful data on causation in this respect. In a study of 110 specimens from the peritoneal cavity after perforation and of 22 intraabdominal abscesses, Brook and Frazier isolated many species.47 Not surprisingly the majority included Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp., Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Clostridium, and Fusobacterium.

PIERRE-SIMON, THE MARQUIS DE LAPLACE (1749-1827)

|

Pierre-Simon Laplace was born at Beaumont-en-Auge, in Normandy, France. Very little is known about his early life, but it is speculated that his father was either a laborer or a farmhand. Laplace sought a life in education and did so initially by becoming an usher in the school at Beaumont. He then moved to Paris after the paper he wrote on the principles of mechanics caught the attention of Jean le Rond D’Alembert, then at the height of his fame. With D’Alembert’s support, Laplace obtained a position as professor of mathematics in the École Militaire de Paris, continuing his investigations in the field and writing papers on integral calculus, finite differences, and differential equations. He described his astronomical findings in Mécanique Céleste [celestial mechanics] and ultimately came to be regarded as the Isaac Newton of France. He became a member of the Academy of Science in 1785. Laplace built on the work initiated by Young; the Young-Laplace equation explains why the cecum is the part of the colon most susceptible to perforation because it has the greatest diameter. The formula states that the tension on the wall is directly proportional to the diameter, and the pressure within is inversely proportional to the wall’s thickness. Laplace also had a need for recognition. He briefly held the post of Minister of the Interior under Napoleon Bonaparte, but after 6 weeks he was dismissed from the court and joined the Senate. During his later years, Laplace lived most of the time at Arcueil, where he had a country house. In this peaceful retirement he pursued his studies, receiving distinguished visitors from all parts of the world. He died in Paris on March 5, 1827, just short of his 78th birthday. His last words were, “Ce que nous connaissons est peu de chose; ce que nous ignorons est immense” [what we know is little; what we are ignorant of is immense]. He is remembered for his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. His works in these fields became the cornerstone for a multitude of principles and other further research. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre-Simon_Laplace.jpg; http://www. maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Laplace/RouseBall/RB_Laplace. html; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Young%E2%80%93Laplace_ equation; Bayless, Theodore M. Advanced therapy in gastroenterology and liver disease. Hamilton, Ontario; BC Decker Inc; 2005:503; with appreciation to Seth A. Stein, MD.)

▶ ETIOLOGIC FACTORS

Various factors that may be important with respect to causation and clinical significance are considered later.

Age

From a historical standpoint, diverticulitis in younger patients (younger than the age of 50 years) has been described as more virulent and more likely to be associated with complications and more likely to require resection.67,68,217 Young individuals have been variably defined as younger than 50 years in some series and younger than 40 or 45 years old in other reports. Despite the definition of what age defines “young patients,” all series of so-called younger patients with acute diverticulitis have noted a striking male predominance in contrast to those who are older. Also, the older patients have a slight female predominance.69 Earlier series of young persons in the precomputed tomography scan era have shown a large percentage of patients who underwent resection, presumably because they were frequently diagnosed preoperatively as having appendicitis. These individuals then underwent laparotomy and subsequent resection when diverticulitis and not appendicitis was encountered. Currently, such patients would most likely be correctly diagnosed as having acute diverticulitis on computed tomography (CT) scan preoperatively and treated with initial medical management of bowel rest and antibiotics. The current management of young patients with diverticulitis continues to be a source of considerable controversy and is discussed later in this chapter.

Sex and Heredity

Most studies report that diverticular disease is more common in women, the incidence increasing with advancing age.228 Results of postmortem examinations usually place the frequency at about 50%. However, the correlation between the incidence of the condition and the presence or duration of symptoms is less clear. For example, young men are more likely to require surgical intervention for complications than are elderly patients, some even during the initial attack.99 According to the Mayo Clinic experience (Rochester, MN), women tend to present about one-half decade after men with complications requiring surgery.188 An inheritable tendency may also be a factor. Resection has been performed for acute disease in identical twins,101 and Corman reported operating upon three siblings with acute, complicated diverticulitis.66

Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Numerous studies have suggested an association between steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and the development of complications of diverticular disease.50,65,197,337 Possible explanations include a direct effect on the bowel wall through inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis itself, or the inhibitory effect of leukocyte function with failure of the immune system to localize the process. In case-controlled studies, it has been consistently found that more individuals with complicated diverticulitis were taking NSAIDs than were randomly selected other groups.50,337 In addition to NSAIDs, opioid analgesics and corticosteroids are positively associated with the risk of complications in individuals with diverticular disease.197 The effect of drugs on acute diverticulitis is considered further later.

Immunocompromised

An immunocompromised patient is predisposed to infection, and someone with diverticular disease is at an increased risk for the development of diverticulitis. Such patients often mask typical symptoms and signs of an acute inflammatory process of the abdomen. Those with connective tissue disorders are often immunocompromised because of corticosteroids, but they appear to have an additional risk of complicated diverticulitis related to the underlying disorder (see later). Uncomplicated diverticular disease does not appear to be causally related to the immunocompromised condition.

Smoking, Alcohol, Caffeine, and Exercise

Aldoori and colleagues studied a population of 47,678 American males over a 4-year period. During this time, there were 382 newly diagnosed cases of diverticular disease.9 There was no significant difference in alcohol or caffeine consumption when compared with the general population. Others have shown, however, that the risk of diverticulitis was significantly increased in patients with alcoholism.310 Another study from Aldoori’s group, smoking was found to be a modest risk factor in patients with symptomatic disease.9 In a small report in which 45 patients requiring admission to hospital for diverticular disease were compared with 35 asymptomatic individuals, smoking was related to complications (odds ratio [OR] = 2.9).224 There is also evidence that diverticular disease may be associated with lack of exercise.8

▶ DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

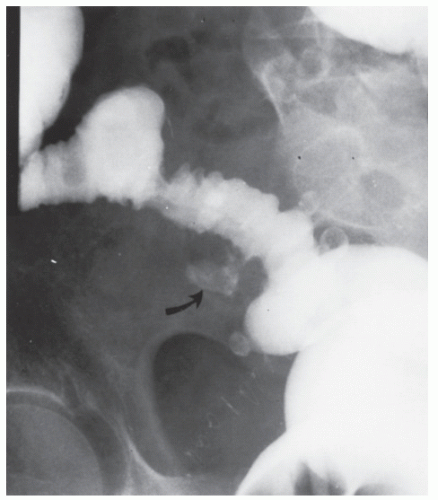

The specific forms of presentation of diverticular disease will be discussed later after a consideration of the differential diagnosis. In all cases, it is important to exclude other possible causes of symptoms that might simulate diverticular disease. To do so, colonoscopy and CT scan with or without contrast are now the most frequently requested investigations. Conventional barium enema is still a useful test, but radiologists are generally hesitant to perform it, preferring CT. This is unfortunate because barium enema is capable of visualizing a small perforation not demonstrated on CT (Figure 27-6).

FIGURE 27-6. Perforation of diverticulum demonstrated by contrast enema (arrow) in a renal transplant patient. No symptoms were apparent except that the patient felt a mass. |

Carcinoma

Colonoscopy

The possibility of carcinoma is likely to be considered more in the elective investigation of the patient. In most cases, this is easily excluded by colonoscopy, but when there is a degree of inflammation and thickening of the bowel wall or a stricture, it may not be possible to enter the sigmoid colon with the instrument.73,95,186,336 Even in the noninflamed bowel, the sigmoid colon may be quite narrow because of thickening of the muscularis propria. Dean and Newell reported 36 patients in whom barium enema examination had suggested the possibility of carcinoma, but it was possible to visualize the diseased segment in only half the cases, although they were able to diagnose carcinoma in 4 patients and to exclude it in 5.73 Max and Knutson performed colonoscopy in 26 patients with an inflammatory stricture in whom radiologic examination had shown an area that raised a suspicion of carcinoma.185 In 19, the questionable area was completely visualized, and in every individual successfully examined, the diagnosis was proven correct.

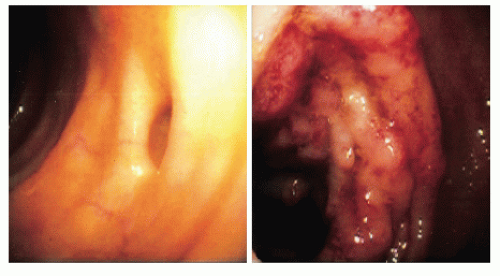

The surgeon can feel assured only if the entire mucosa has been visualized and appears intact. Erythema and edema of the bowel wall may be seen (Figure 27-7), and occasionally pus may be observed to exude from one of the orifices. In such cases, CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) colonography may be helpful. In acute diverticulitis, the clinical picture and the findings on CT will usually be sufficient to exclude a carcinoma. The poor correlation for barium enema of approximately 30% between radiologists reported by Parks and coworkers now 30 years on is no longer relevant.231

Colonoscopy is not without hazard. Overt perforation through a thin-walled diverticulum or walled-off abscess in a patient with acute diverticulitis is possible.336 Examination under such a circumstance is probably contraindicated, but as the individual’s symptoms improve, colonoscopy should be performed if the differential diagnosis is still in question. Very rarely carcinoma can arise in a diverticulum.56

Computed Tomography

CT is the imaging modality of choice to distinguish suspected cancer or diverticular disease. Signs of bowel wall thickening, increased soft tissue density in the pericolic fat, and soft tissue masses related to diverticulitis are helpful for confirming the diagnosis (Figure 27-8), but a perforated carcinoma may exhibit the same changes on CT.174,238 Some investigators have confirmed the value of CT in identifying intra-abdominal abscess and phlegmon, bladder wall thickening and edema, and extracolonic extension, as well as relatively subtle features suggestive of diverticulitis.238 However, the decision for or against surgical intervention in a patient with a mass in whom colonoscopy and CT do not give a clear diagnosis will be based on clinical grounds. Even when surgery is undertaken, especially in the acute circumstance, it may not be possible to distinguish tumor from a diverticular phlegmon.

Padidar and colleagues compared the CT scans of 69 patients with proven acute diverticulitis with 29 patients with carcinoma of the sigmoid.218 When they analyzed the radiologic signs of fluid at the base of the mesentery and engorgement of the sigmoid vessels, they reported sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values for each sign of 36%; 90% and 89%; and 29%, 100%, and 100%, respectively. They concluded that these features could be helpful in distinguishing the two pathologies. Goh and coworkers compared quantitative CT perfusion measurements with conventional morphologic appearances in three groups of patients: sigmoid cancer (20), acute diverticulitis (20), and inactive diverticular disease (20).108 They found that the former were more accurate in differentiating cancer from diverticular disease, with blood flow and blood volume having a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 70% to 75%.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Many patients with diverticula have symptoms that are indicative of IBS. IBS itself is estimated to affect up to one-fourth of the population of Western countries. Unfortunately, the condition is not well understood (see Chapter 4). Many people with diverticular disease do not have symptoms specifically related

to the condition. This implies that surgical extirpation of the affected bowel will not necessarily relieve the patient’s symptoms. Breen and colleagues found that no inflammation was present in 28% of surgical specimens removed for diverticular disease.43 These individuals probably had an IBS.

to the condition. This implies that surgical extirpation of the affected bowel will not necessarily relieve the patient’s symptoms. Breen and colleagues found that no inflammation was present in 28% of surgical specimens removed for diverticular disease.43 These individuals probably had an IBS.

Patients with IBS comprise the vast majority of patients seen by gastroenterologists. The condition is also the single most common reason for referral to major medical clinics. In England, one-fifth of a sample from the general population had experienced abdominal pain more than six times in 1 year.172 Approximately one-fourth of a similar sample in the United States reported abdominal pain more than six times in the year. IBS is not a precursor of diverticulosis as demonstrated by longitudinal study.179 Furthermore, there is no evidence that the symptoms of IBS are affected by the presence of diverticula.216,285,286,307

The diagnosis of IBS is by exclusion, but the history can sometimes be helpful in suggesting its presence. The diagnostic criteria have been updated according to the Rome III criteria in 2006 as follows:

Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month during the previous 3 months that is associated with two or more of the following176:

Relieved by defecation

Onset associated with a change in stool frequency

Onset associated with a change in stool form or appearance

Supporting symptoms include the following:

Altered stool frequency

Altered stool form

Altered stool passage (straining and/or urgency)

Mucorrhea

Abdominal bloating or subjective distension

Still, there may be difficulty in determining whether symptoms are due to diverticular disease or to IBS, and the extent of the diverticula may not be helpful. Severe diverticular-like symptoms may occur in the absence of diverticula as reported in a study of 88 patients with IBS in whom diverticula were present in only 24%.126 Ritchie found that a high proportion of patients with IBS had a lower threshold for pain when the colon was distended with a balloon, similar to that observed in individuals who had diverticular disease.254 Leukocytosis and signs of peritoneal irritation do not occur in IBS, but abdominal tenderness and even the suggestion of a mass in the left lower quadrant may be evident.

In a review, Bergamaschi has discussed the question of interradiologist variation in the diagnostic distinction between diverticulitis and diverticulosis by contrast enema or ultrasound.34 The sensitivity and specificity of the latter drops off significantly when the results of round-the-clock ultrasound are compared with those of dedicated practitioners. Contrast studies and endoscopy may reveal no abnormality, but many patients are found to have coincidental diverticula with or without evidence of “bowel spasm.”

With respect to the apparent difference between the sexes in the results of surgery, men are less likely to have functional bowel complaints. Hence, misinterpretation of symptoms is less of a problem, and the correlation with radiologic and clinical findings is usually self-evident. Thörn and colleagues showed that individuals with functional symptoms or symptoms suggestive of an irritable bowel before surgery predicted a less successful result from surgery.308

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease can demonstrate signs, symptoms, and findings that may mimic diverticulitis. These include segmental colitis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Ischemic colitis may also mimic acute diverticulitis.

Segmental Colitis

In recent years, the condition of segmental colitis associated with diverticula (SCAD) has been recognized (Figure 27-9). This uncommon condition is an inflammation localized to the sigmoid colon and in the presence of diverticula. Freeman identified 24 patients over a follow-up period of 2 to 16 years who were found to have diverticular disease with symptoms of bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.98 Eighty percent

responded to 5-aminosalicylic acid medication, but spontaneous remissions also occurred. The condition was not related to neoplasia.

responded to 5-aminosalicylic acid medication, but spontaneous remissions also occurred. The condition was not related to neoplasia.

In a systemic review, Mulhall and colleagues identified 18 articles out of a total of 478 that were deemed to be eligible for evaluation.205 Most of the 478 were not relevant to inflammatory bowel disease, most were retrospective, and one-third were case reports. The 18 articles included 227 patients of average age of 63.7 ± 5.2 years. Sixty-one percent were male. Of the 227 patients, 162 (71%) were classified as having diverticular-associated colitis, of whom 142 were managed conservatively and 28 by surgery. Recurrent symptoms developed in 37 (26%) over a 3-year period. In a prospective multicenter study of four units in Italy, Tursi and colleagues reviewed 8,525 colonoscopies.320 Of these, 6,041 were performed for symptoms. The target population of patients with diverticula was divided into three groups: those with ulcerative colitis (UC) and diverticula, SCAD with segmental inflammation away from the orifices of the diverticula, and acute uncomplicated diverticulitis (AUD) with the inflammation involving the diverticular orifices. The conclusion from this study was that SCAD and UC in the presence of diverticula is uncommon.

Crohn’s Disease

It may be difficult to differentiate Crohn’s disease from diverticulitis. There are several symptoms, however, that may lead the surgeon to suspect the possibility of the former, especially if the patient complains of diarrhea and rectal bleeding. The presence of an anal lesion is also suggestive (see Chapters 14 and 30). Rectoscopy reveals a normal rectum in diverticulitis, whereas with Crohn’s disease the rectum may or may not be spared. At laparotomy, it may still be impossible to distinguish between the two conditions, even if the resected specimen is opened. Usually, however, in diverticulitis the mucosal surface, although edematous, is otherwise normal. Evidence of granularity or ulceration is indicative of inflammatory bowel disease. A frozen-section examination is not advised because it will not affect the type of operation. The presence of granuloma formation does not necessarily indicate Crohn’s disease because foreign body giant cells can be seen with diverticulitis as a reaction to pericolonic abscess.200 Crohn’s disease is second only to diverticular disease as a cause of intestinal fistulization into the bladder.201

Berman and colleagues reported 25 patients who required colonic resection for “diverticulitis” on a second occasion, and all eventually proved to have Crohn’s disease.35 In many instances, Crohn’s colitis was suspected, but not until after a subsequent resection with histopathologic confirmation. Symptoms and signs of recurrent illness were similar to those present when the patient was initially seen, that is, before the first operation. In these individuals, there was often a history of smoldering illness in contrast to the more episodic nature of the symptoms in patients with diverticulitis. Age was not particularly helpful in distinguishing the two conditions because in the older age group especially Crohn’s disease often tends to involve the large rather than the small bowel. The presence of extracolonic manifestations, such as pyoderma or arthritis, unusual technical difficulty in performing the resection, and failure of the colonic inflammation to resolve, should lead the surgeon to suspect Crohn’s disease.

Ulcerative Colitis

The distinction between acute diverticulitis and ulcerative colitis should not be difficult. Rectoscopy virtually always reveals proctitis in patients with ulcerative colitis (see Chapter 29). The importance of performing even a limited proctoscopy before embarking on surgery for acute diverticulitis cannot be overestimated. The presence of inflammatory changes in the rectum or a high index of suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease would certainly indicate the need for medical management or an alternative operative approach.

Ischemic Colitis

Ischemic colitis may pose a problem in differential diagnosis. This is particularly true if the ischemic changes include the rectosigmoid. However, patients with disease limited to this area usually present with frequent bowel movements and rectal bleeding. Abdominal pain suggests a more fulminant and extensive manifestation of ischemic colitis. The presence of thumb printing on the plain abdominal film, particularly in the splenic flexure region, suggests ischemia (see Chapter 28).

Other

Acute appendicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and urinary tract disease such as infection and nephrolithiasis are important to exclude.

▶ CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

Acute Diverticulitis

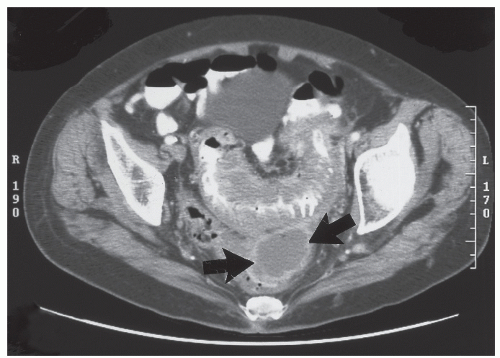

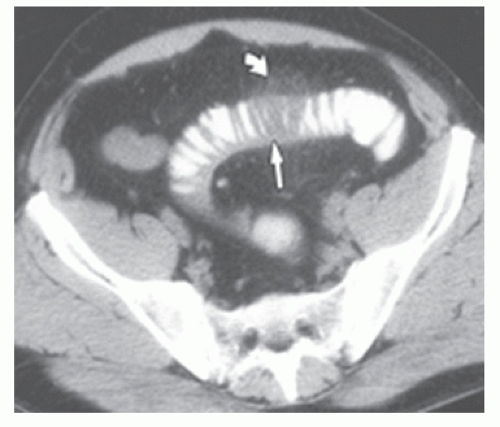

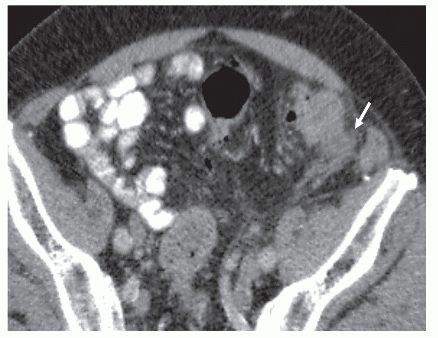

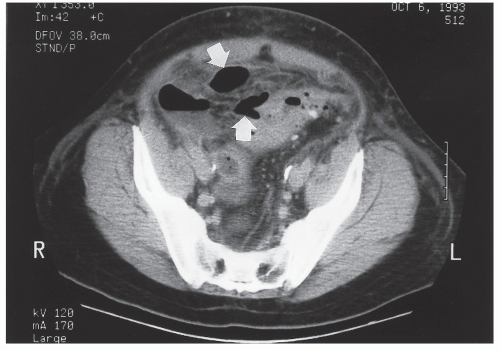

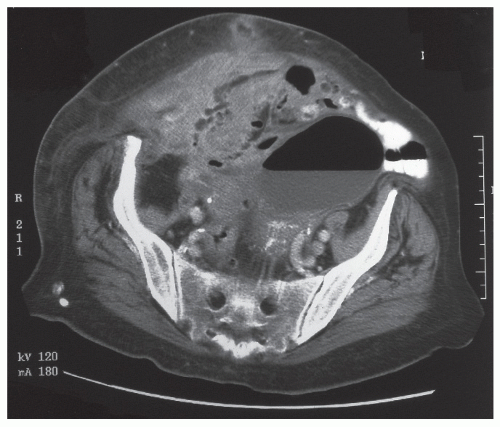

Acute diverticulitis is a common emergency. In most patients, it is mild and may even be treated as an outpatient with antibiotics. Imaging is not usually contributory in such individuals. If the condition does not settle or worsen, imaging can then be carried out. Many patients, however, will require admission to hospital owing to the severity of the clinical condition. It is now accepted that in patients with general or localized physical signs, or where there is a suspicion of a septic complication, a CT scan is indicated as soon as can reasonably be obtained. In acute diverticulitis, there is thickening of the wall of the sigmoid colon in most cases (>4 mm is taken as indicative), with evidence of inflammation (which may be extraluminal such as fat

stranding [Figure 27-10]). It will also demonstrate whether local paracolic or pelvic abscess formation has occurred (Figure 27-11), or whether there is evidence of extraluminal gas or liquid suggesting peritonitis (Figure 27-12).

stranding [Figure 27-10]). It will also demonstrate whether local paracolic or pelvic abscess formation has occurred (Figure 27-11), or whether there is evidence of extraluminal gas or liquid suggesting peritonitis (Figure 27-12).

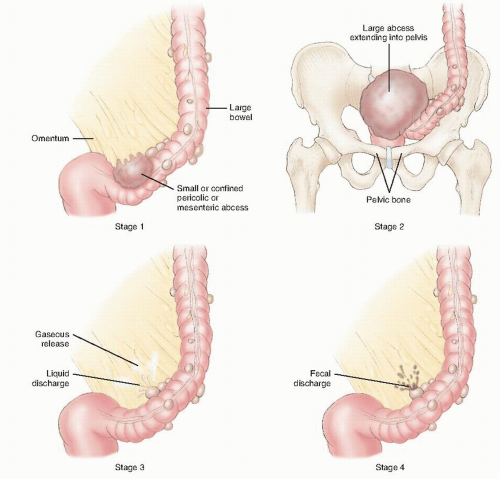

Acute diverticulitis can either be an uncomplicated inflammation of the sigmoid colon without perforation, local or free, or it may be associated with perforation which if contained will be manifested as a local abscess, or if free, as peritonitis. Peritonitis may be purulent or fecal.

Complicated diverticulitis has been classified by Hinchey and colleagues129 as follows (Figure 27-13)

Stage I—Pericolic abscess or phlegmon

Stage II—Pelvic, intra-abdominal, or retroperitoneal abscess

Stage III—Generalized purulent peritonitis

Stage IV—Generalized fecal peritonitis

E. JOHN HINCHEY (1934-PRESENT)

|

John Hinchey was born in Ontario, Canada. He attended King George School and the Belleville Collegiate Institute prior to enrolling in the Queen’s University Medical School in Kingston, graduating in 1959. He served his internship and surgical residency at the Montreal General Hospital. From 1962 to 1966, he was involved in research both at the University Surgical Clinic and in the Department of Surgery at McGill University in Montreal. He went on to achieve his master of sciences and became a fellow of both the Royal College of Surgeons of Canada and the American College of Surgeons. Although serving as an assistant surgeon at the Montreal General Hospital, he began to explore the concept of different approaches to the management of complicated diverticulitis based on the severity of the presentation. However, he credits the famous Australian colon and rectal surgeon, E.S.R. Hughes for initiating the concept 10 years earlier. His ultimate concept of staging evolved over a number of years, culminating in the paper in which he described his four stages. Hinchey has held teaching appointments in the department of anatomy and physiology and ultimately rose to become professor of surgery and director of the Division of General Surgery at Montreal General Hospital/McGill University. Among his many recognitions, he has received the honor of John R. Markle Scholar in Academic Medicine. He is a member of numerous surgical societies, including the American Surgical Association, and served as president of both the Canadian Association of Clinical Surgeons and the Canadian Association of General Surgeons. He has also served as chairman of the Examining Board for General Surgery of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Upon achieving emeritus status in 1999, he became director of the Surgical Scientist Program at McGill.

FIGURE 27-11. Computed tomography showing acute diverticulitis with paracolic abscess formation (arrow). |

Clinical Presentation History

Patients with acute diverticulitis complain primarily of abdominal pain. There may be a prior history of such complaints or of “diverticulitis” or “diverticular disease.” John and colleagues, in reporting a series of 100 patients seen as an emergency with a suspected diagnosis of diverticular disease, found that 54 had had a past history of similar abdominal pain.147 The pain is usually located in the left lower quadrant and tends to be constant rather than colicky in nature. It may radiate to the back, left flank, groin, and leg, although these features may also be seen with an irritable bowel. The duration and severity of symptoms are quite variable, depending on whether the patient has a localized or a diffuse process. Nausea and vomiting are uncommon unless there is some element of intestinal obstruction. A change in bowel habit is frequently observed. Additionally, there may be an absence of bowel movements, or the patient may be experiencing diarrhea.

FIGURE 27-12. Computed tomography demonstrates perforated diverticulitis with extraluminal gas (arrows). |

Individuals with acute diverticular disease often mention urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency, nocturia), which may be attributable to irritation by the inflammatory mass on the wall of the bladder. A urinary tract infection may imply communication with the bowel (see later). Passage of gas in the urine or per vaginam is diagnostic of a fistula (see also later). Fever is also commonly observed in those with acute diverticulitis. This is usually of a low grade, but if peritonitis develops or if an abscess is present, the temperature can be considerably elevated or even depressed in patients with septic shock.

Rectal bleeding has been thought to be part of the symptom complex of diverticulosis, but there is confusion on this issue. Massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the presence of diverticular disease can be caused by a vascular malformation rather than diverticulosis, but patients with diverticular disease may also bleed from a diverticulum.40 This aspect of the presentation is discussed in Chapter 28.

Physical Examination

Physical examination will vary according to the severity of the condition. The patient may be systemically well with mild tenderness localized to the left iliac fossa. The white blood cell count may be normal or mildly raised. The Creactive protein (CRP) level is a more sensitive indication of inflammation and may well be raised when the white blood cell count is normal. In a series of 100 patients admitted as an emergency with a clinical diagnosis of diverticular disease, the CRP was 281 mg/L in those with complicated and 54 mg/L in those with uncomplicated disease.147 In contrast, the patient may be grossly septic, either with peritonitis or with localized abscess. In such a person, tenderness will be marked, with guarding and rigidity if there is peritonitis. Bowel sounds may be absent. In short, the clinical features of an acute abdominal catastrophe may be evident. Tenderness and a mass in the pelvis from a sigmoid phlegmon or abscess may be noted on rectal or vaginal examination. Also, an abdominal mass may be felt. Extraperitoneal infection can present with back, buttock, and hip and leg pain; a positive psoas sign; a lower extremity abscess; perineal and scrotal pain and swelling; and subcutaneous, mediastinal, and cervical emphysema.245 Perforation below the peritoneal reflection can lead to a buttock abscess and a consequent anorectal fistula (see Chapters 13 and 14).78 Pathways of extraperitoneal pelvic abscess spread to the gluteal area are through the suprapiriformis and infrapiriformis fossae, to the external genitalia via the obturator canal, and to the ischiorectal fossa through the pelvic floor (Figure 27-14).

Imaging

Data are available on the accuracy of water-soluble contrast enema (CE), CT, ultrasonography (US), and MRI in diagnosing acute diverticulitis. Plain x-ray of the chest and abdomen may show free gas and may reveal nonspecific features in up to 50% of patients with diverticulitis and is, therefore, considered inadequate in giving sufficient information in most cases.190 In a useful systematic review, Liljegren and colleagues carried out a search of the literature for articles dealing with imaging of acute diverticular disease with the particular purpose of assessing their quality.175 They found 49 of which only 20 were found to pass the test of quality. Of the 29 excluded, 14 were reviews, 6 did not use a reference standard, 8 gave no information on specificity, and 1 was duplicated. Of the 20 included articles, there was 1 (ultrasound compared with CT) with level 1b evidence,240 3 (ultrasound 2, magnetic resonance 1) with 2b level,5,326,343 with the remaining being level 4.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography began to be used for the diagnosis and assessment of acute diverticulitis in the 1980s.21,27,123,165 Labs and colleagues evaluated 42 patients suspected of having diverticulitis, of whom 22 were found to have a complication and 20 without a complication.165 Of the 22 patients, 10 had an abscess and 12 a colovesical fistula. The abscesses were

correctly identified in all cases by the presence of diverticula, a segmentally thickened colon, and an extravisceral fluid collection. An example of acute diverticulitis with abscess formation is shown in Figure 27-8. Only 25% of those studied by contrast enema were thought to have abscesses. Of the 12 patients with a colovesical fistula, this was confirmed by CT through the identification of air in the bladder, thickened colon adjacent to an area of thickened bladder, and the presence of colonic diverticula. Contrast enema identified only three of eight cases with fistula in whom it was performed. Raval and coworkers recommended that CT be performed with the administration of a rectal contrast medium in order to demonstrate the presence or absence as well as the origin of the colonic inflammation (Figure 27-15), to assess pericolic extent, and to confirm the presence or absence of a colovesical fistula (Figure 27-16).244

correctly identified in all cases by the presence of diverticula, a segmentally thickened colon, and an extravisceral fluid collection. An example of acute diverticulitis with abscess formation is shown in Figure 27-8. Only 25% of those studied by contrast enema were thought to have abscesses. Of the 12 patients with a colovesical fistula, this was confirmed by CT through the identification of air in the bladder, thickened colon adjacent to an area of thickened bladder, and the presence of colonic diverticula. Contrast enema identified only three of eight cases with fistula in whom it was performed. Raval and coworkers recommended that CT be performed with the administration of a rectal contrast medium in order to demonstrate the presence or absence as well as the origin of the colonic inflammation (Figure 27-15), to assess pericolic extent, and to confirm the presence or absence of a colovesical fistula (Figure 27-16).244

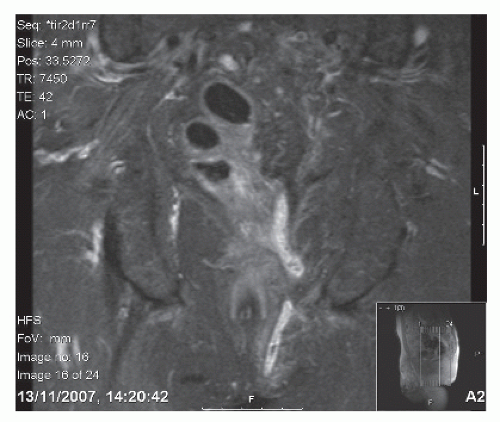

FIGURE 27-14. Magnetic resonance scan of fistula from sigmoid colon to the perineum in a patient with diverticular disease. |

Hansen and colleagues, in a retrospective study of 243 patients with acute diverticulitis, reported that the sensitivity

of CT was 97.5%, with an overall accuracy of 97.1%.123 A similar sensitivity (98%) was reported by Ambrosetti and colleagues among 470 patients.16 Pradel and coworkers reported a level 1b evidence prospective study of 64 patients with acute diverticulitis in whom the diagnosis was confirmed subsequently in 33, with 24 patients being diagnosed with another disease.240 Seven failed to have their diagnosis established. The diagnosis of acute diverticular disease was confirmed on follow-up of patients with typical clinical features, supplemented by subsequent pathology where available and by colonoscopy. The sensitivity and specificity of CT was 85% and 84%, with a positive predictive value of 81% and a negative predictive value of 88%. CT has also been thought to be particularly valuable in the diagnosis of right-sided diverticulitis (Figure 27-17).™

of CT was 97.5%, with an overall accuracy of 97.1%.123 A similar sensitivity (98%) was reported by Ambrosetti and colleagues among 470 patients.16 Pradel and coworkers reported a level 1b evidence prospective study of 64 patients with acute diverticulitis in whom the diagnosis was confirmed subsequently in 33, with 24 patients being diagnosed with another disease.240 Seven failed to have their diagnosis established. The diagnosis of acute diverticular disease was confirmed on follow-up of patients with typical clinical features, supplemented by subsequent pathology where available and by colonoscopy. The sensitivity and specificity of CT was 85% and 84%, with a positive predictive value of 81% and a negative predictive value of 88%. CT has also been thought to be particularly valuable in the diagnosis of right-sided diverticulitis (Figure 27-17).™

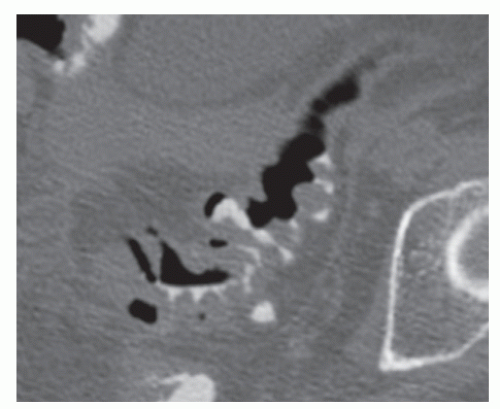

FIGURE 27-15. CT with contrast in the lumen demonstrates configuration of severe diverticular hypertrophy but no associated inflammatory changes or thickening. |

In a recent article, Ambrosetti reviewed his experience based on a long-term prospective study that commenced in 1986.15 He described a series of 355 patients in whom a CT was undertaken shortly after admission. The average followup was 9.5 years. He points out the high sensitivity of CT for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis. There were 132 patients who needed an early operation, and CT correctly diagnosed them in 123 instances. There were four false and five falsepositive results, giving an overall sensitivity of 97%. Of the 79 patients who were initially treated medically but subsequently required early surgery, 42 had had a CT scan. Thirtytwo (76%) were found to have severe changes on the scan, whereas only 74 (24%) of the 303 patients having successful medical treatment did so. Of the 106 patients found on CT to have severe disease, 32 (30%) required early operation compared with 10 (4%) of the 239 patients with moderate CT changes.

FIGURE 27-16. Computed tomography demonstrates an abnormal sigmoid colon with multiple diverticula and with a large amount of air within the bladder consistent with a colovesical fistula. |

CT was also found to be predictive of complications in the long term. In a subgroup of 118 patients followed more than 9.5 years, the greatest complication rate (54% at 5 years) was in CT-severe young patients, and the lowest (19% at 5 years) was in the CT-moderate older patients. Ambrosetti concluded that CT is sensitive at the time of original presentation and is a predictor of failure of medical treatment as well as of long-term, recurrent complications.15

CT as a Predictor of Outcome. Ambrosetti and colleagues reported 107 patients who underwent CT scanning after an initial attack of acute diverticulitis.21 Of these, 24 (22%) continued to have complications, including persistent diverticulitis (9), recurrent diverticulitis (7), stenosis (6), residual abscess (1), and colovesical fistula (1). Eight (44%) of the 18 patients younger than 50 years of age had a poor outcome compared with only 16 (18%) of the remaining 89. Of the 76 patients who showed mild changes on CT, 12 (16%) subsequently experienced a complication compared with 11 (48%) of the 23 patients whose CT showed evidence of persistent abscess formation or localized gas. In a further report of 542 patients

who had the criteria for acute diverticular disease, the same authors reported that 26% of patients with severe findings on CT that had been carried out within 72 hours of admission failed medical treatment. This compared with only 4% in whom the CT findings were moderate. They confirmed that patients with severe CT findings were more likely to have recurrent symptoms than those with moderate changes (36% vs. 17%).16 These differences were statistically significant.

who had the criteria for acute diverticular disease, the same authors reported that 26% of patients with severe findings on CT that had been carried out within 72 hours of admission failed medical treatment. This compared with only 4% in whom the CT findings were moderate. They confirmed that patients with severe CT findings were more likely to have recurrent symptoms than those with moderate changes (36% vs. 17%).16 These differences were statistically significant.

CT Compared with Other Imaging Modalities

WATER-SOLUBLE CONTRAST ENEMA. Ambrosetti and colleagues compared CT with contrast enema in two publications16,19: the first included 420 patients and the second 470, who had both examinations. The results are qualitatively similar. This is not surprising because the second study was an expansion of the patients accrued in the first. The results of the second report are given next. Those attending between 1986 and 1997 underwent a CT and water-soluble CE within 72 hours of admission. Those with peritonitis were operated on immediately and were, therefore, excluded from the study. Of the 470 patients who had had both examinations, 69 were found to have an abscess on CT, but only 20 of these were seen on CE. The overall diagnostic sensitivity of CT and CE was 98% and 92%, a small but statistically significant difference. Severe disease was detected by CT in 26% compared with 9% by CE. It was possible to stratify severity by CT (see previously) into severe and moderate, which were related to failure of medical treatment (26% vs. 19%) and the chance

of a subsequent poor outcome (36% vs. 17%). The authors concluded that CT was better than CE and that CT had the advantage of predicting the outcome more accurately.

of a subsequent poor outcome (36% vs. 17%). The authors concluded that CT was better than CE and that CT had the advantage of predicting the outcome more accurately.

Hansen and colleagues obtained a similar result, reporting a sensitivity of 97.5% for CT and 71.6% for CE in diagnosing acute diverticulitis.123

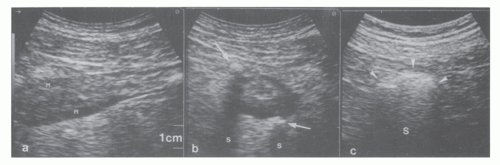

ABDOMINAL ULTRASOUND. A prospective study was undertaken by Pradel and colleagues in 1997 in which 64 patients with a clinical diagnosis of acute diverticulitis and who underwent CT and US were assessed by a blinded observer.240 Subsequent follow-up including colonoscopy and histologic examination of the resected specimen confirmed the condition in 33. There was no significant difference (CT vs. US) in the sensitivity (91% vs. 85%), specificity (77% vs. 84%), positive predictive value (PPV) (81% vs. 85%), and negative predictive value (NPV) (88% vs. 84%). CT and US identified abscess formation in 6 patients, and CT demonstrated an abscess in 3; this was not shown on US. The authors concluded that there was little difference between the studies.

Other reports of ultrasound have supported this finding. Verbanck and colleagues carried out a level 2b evidence prospective study of 123 patients with a clinical diagnosis of acute diverticulitis.326 Of these, the diagnosis was subsequently confirmed in 52. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 84.6%, 80.3%, 76.0%, and 87.7%, respectively. They found that hypoechoic bowel wall with a thickness of more than 4 mm was present in 44 of the 52 patients and was therefore a useful radiologic sign indicating acute diverticulitis when clinical suspicion was present. Zielke and colleagues, in a prospective observational level 2b evidence study of 57 consecutive patients, used length and thickening of the bowel wall as criteria for inflammation and involvement.343 The diagnosis of acute diverticular disease was made by US in 48, giving an accuracy of 84%, with 9 false negatives and 3 nondiagnostic results. Schwerk and colleagues carried out high resolution ultrasound in 130 patients who presented with “abdominal complaints.”280 Of these, 52 (40%) were ultimately confirmed as having diverticulitis. Clinical examination had shown the diagnosis to be “highly suspected,” “possible or equivocal,” or “very unlikely” in 19 (36.5%), 24 (46.2%), and 9 (17.3%), respectively. Ultrasound was highly accurate, with a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 98.1%, 97.5%, 96.2%, and 98.5%, respectively. The signs of particular value were a hypoechoic thickened wall and a “target-like” appearance of the bowel in cross section. This latter finding is felt to be due to inflammatory changes and muscular thickening of the bowel wall (Figure 27-18). Of the 13 patients with abscess formation, this was correctly identified in 12, 7 of which were successfully drained percutaneously. A hemispheric mass, the “dome sign,” has also been described.158

Computed Tomographic Colonography (CTC). Computed tomographic colonography has been compared with conventional colonoscopy in patients with diverticular disease. Lefere and colleagues studied 160 consecutive patients and found that CTC demonstrated wall thickening in 55 (36%), diverticula in 52%, and fecoliths in 39%.171 The results were similar to that of colonoscopy. In a similar study, Hjern and colleagues, in comparing CTC with colonoscopy in 50 patients by blinded evaluation of the images, demonstrated diverticular disease in 96% and 90%, respectively.130 The rate of agreement between them was good (k = 0.64). Gollub and coworkers performed CTC on 150 patients and found that mucosal thickening in diverticular disease was related to decreased sigmoid distensibility.109 These results suggested that CTC may be useful in selected cases in whom colonoscopy is either not possible or too dangerous. Flor and associates also found good sensitivity and specificity for CTC (Figure 27-19).94

Magnetic Resonance Colonography

Ajaj and colleagues investigated magnetic resonance colonography (MRC) in a prospective level 2b study using dark-lumen MRC in 40 patients presenting with suspected diverticulitis.5 T1-weighted images were taken after an aqueous enema and gadolinium-based contrast. Bowel wall thickening and pericolic reaction, including mesenteric infiltration indicating diverticular disease, were seen in 23 patients. The remaining 17 were classified as not having diverticular disease, 4 of whom were judged to be false negatives. Of the 23 positive patients, there were 3 false positives due to carcinoma. There is clearly the need to exercise caution in interpreting the images, but the authors concluded that MRC is a useful investigation, particularly when colonoscopy is either not possible or not indicated as a consequence of severe inflammation. MRC has the additional advantage of being able to demonstrate other colonic pathology.

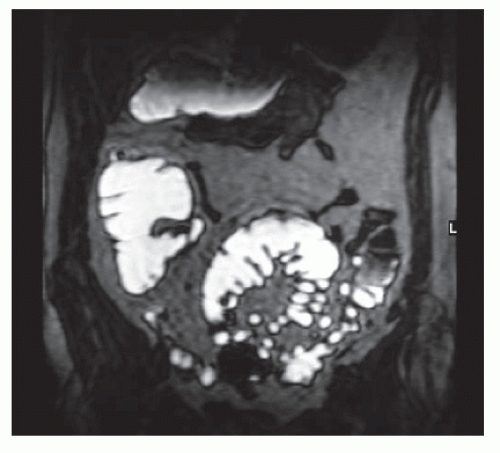

In another study, MRI-based colonography was compared with spiral CT in 14 patients.276 The technique involves the administration of an magnetic resonance (MR) opaque enema. In this study, 56 bowel segments were examined, of which 52 were judged to be of adequate image quality. The authors concluded that MRC was as good as CT without the concern for ionizing radiation. It was conceded, however, that there were differences in the availability of the two methods. An example of an MRC image in diverticular disease is shown in Figure 27-20.

Comment

When the patient is admitted with a suspected diagnosis of acute diverticular disease, the choice of imaging will depend on the severity of the condition. This is based on clinical assessment. Because the purpose is to aid in diagnosis and to assess the severity of the condition, imaging should be used in an intelligent manner. Thus, if the clinical diagnosis is one of mild diverticulitis, then it is reasonable to treat with antibiotics without any imaging. As will be outlined in the following section, when medical management is considered, many such patients can be treated as an outpatient with the expectation of rapid resolution of symptoms. To submit such individuals to a CT scan will usually not contribute to decision making and will only incur radiation and expense. It is a little publicized fact that a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is equivalent in radiation to 300 to 400 chest x-rays. However, if the patient’s condition deteriorates, a CT scan or ultrasound will be necessary.

It is generally believed that CT scan is the diagnostic modality of choice in this condition, but it should be noted that the results of ultrasound are only slightly inferior to CT. However, its ability to detect abscess formation is significantly below that of CT. There is also the value that CT offers in predicting the clinical response to medical treatment and the possibility of long-term complications. Additionally, there is the advantage that the clinician can interpret the images, whereas with ultrasound, someone familiar with the technique is required to inform the clinician of the radiopathologic situation. There is, however, merit in considering ultrasound in a patient who may require more than one attempt at percutaneous drainage. If a collection is accessible to ultrasound drainage, this may be the better option because there is no radiation hazard with this technique. Clinical discretion always should be used in weighing whether to image and if so what form to use.

▶ TREATMENT

Acute Diverticulitis (Uncomplicated)

General Statement

In 2009, Etzioni and colleagues published data on the overall burden of diverticulitis in the United States and on the incidence of surgery performed in those admitted with acute diverticulitis.86 They used the NIS for 1998 and 2005 in order to analyze the outcome of 267,000 admissions for acute diverticulitis and 33,500 elective operations in patients who had had an acute attack. From 1998 to 2004/2005, there was a fall in the proportion of persons who underwent surgery following admission for acute diverticulitis from 17.4% to 14.4%. The prevalence of stoma creation was unchanged at 56.0% and 56.5%. Percutaneous drainage was carried out in only 1.4% of patients in 1998 but rose to 2.5% by 2005. It is evident, therefore, that the vast majority of patients admitted with acute diverticulitis are managed medically. Surgery is indicated for patients with peritonitis, for those with an abscess which does not resolve with antibiotics, or with a minimally invasive drainage procedure (or if it is inaccessible to drainage), and when there is failure to improve more than 24 to 48 hours after initiating medical treatment. The reader is referred to recent reviews on this subject.120,142,143 and 144,177,297

Risk Factors for Surgery

Age

Age younger than 50 years has been regarded by many to be a risk factor that increases the chance of surgery being required.2,217,271 Mäkelä and colleagues, in a series of 366 patients followed for more than 10 years, found that males younger than 50 years had more initial operations and

more recurrences than other groups.183 A similar observation was made by Chautems and coworkers in 118 patients followed prospectively.52 Other articles from the same unit based on the same patient group support the view that patients younger than 50 years were significantly more prone to recurrence and complications after initially successful conservative treatment, whereas older individuals required operation significantly more often during their initial hospitalization.21,22 Vignati and colleagues reported 40 patients with acute diverticulitis younger than 50 years and who were followed for a minimum of 5 years.329 Ten underwent immediate surgery. During follow-up, a further 10 of the remaining 30 patients underwent an operation. Although the authors concluded that surgery in this population following a single episode of diverticulitis that resolves was not recommended, the opposite view could be taken from the data. The risk in young patients led Konvolinka and associates to the opinion that any patient younger than 40 years should be considered for surgery even after one attack.157 Spivak and colleagues evaluated 63 patients younger than 45 years who had been treated for a presumptive diagnosis of acute diverticulitis.289 Two-thirds responded to antibiotics and bowel rest, whereas the remainder required an emergency operation. At surgery, 20% were found to have appendicitis (which they point out must always be considered in the differential diagnosis). However, others conclude that young patients do not have a more virulent form of the disease nor is the risk of recurrence greater than in older patients. Biondo and coworkers divided 327 patients presenting with acute diverticulitis into two groups.38 This included 72 younger than 50 years of age and 255 older than 50 years. In those treated medically, recurrence occurred in 25.5% and 22.3% in each group, respectively. Operative mortality for elective resection was 0% and 2.2% and for emergency surgery, 0% and 34.0%. The authors concluded that the disease was not more aggressive in younger patients.

more recurrences than other groups.183 A similar observation was made by Chautems and coworkers in 118 patients followed prospectively.52 Other articles from the same unit based on the same patient group support the view that patients younger than 50 years were significantly more prone to recurrence and complications after initially successful conservative treatment, whereas older individuals required operation significantly more often during their initial hospitalization.21,22 Vignati and colleagues reported 40 patients with acute diverticulitis younger than 50 years and who were followed for a minimum of 5 years.329 Ten underwent immediate surgery. During follow-up, a further 10 of the remaining 30 patients underwent an operation. Although the authors concluded that surgery in this population following a single episode of diverticulitis that resolves was not recommended, the opposite view could be taken from the data. The risk in young patients led Konvolinka and associates to the opinion that any patient younger than 40 years should be considered for surgery even after one attack.157 Spivak and colleagues evaluated 63 patients younger than 45 years who had been treated for a presumptive diagnosis of acute diverticulitis.289 Two-thirds responded to antibiotics and bowel rest, whereas the remainder required an emergency operation. At surgery, 20% were found to have appendicitis (which they point out must always be considered in the differential diagnosis). However, others conclude that young patients do not have a more virulent form of the disease nor is the risk of recurrence greater than in older patients. Biondo and coworkers divided 327 patients presenting with acute diverticulitis into two groups.38 This included 72 younger than 50 years of age and 255 older than 50 years. In those treated medically, recurrence occurred in 25.5% and 22.3% in each group, respectively. Operative mortality for elective resection was 0% and 2.2% and for emergency surgery, 0% and 34.0%. The authors concluded that the disease was not more aggressive in younger patients.

Guzzo and Hyman reported the outcome of 762 patients presenting with sigmoid diverticulitis at one institution over an 11-year period.116 Of these, 238 (31%) underwent immediate surgery. The risk of this operation was no different in patients older than or younger than 50 years of age. During follow-up, however, elective surgery was carried out in 40% of those younger than 50 years compared with 26% of those older than 50. Of the 196 patients younger than 50 years who were treated medically, only 1 (0.5%) developed a late perforation. Owing to the infrequency of serious later complications, the authors concluded that elective surgery in young patients having had an acute episode of diverticulitis is not warranted.

Comment. Many of the studies estimating the effect of age on outcome are small and lack definitions of what is severe and nonsevere disease. Moreover, there may have been a misdiagnosis of diverticular disease in some cases. The available data give little evidence to support a different management strategy in younger individuals.

Sex