Congenital Anomalies of the Female Urethra

Distal Urethral Stenosis in Infancy and Childhood (Spasm of the External Urinary Sphincter) and Dysfunctional Voiding

There has been considerable confusion about the site of lower tract obstruction in young girls who have enuresis, a slow and interrupted urinary stream, recurrent cystitis, and pyelonephritis and who, on thorough examination, often exhibit vesicoureteral reflux. Treatment has been directed largely to the bladder neck on rather empiric grounds. Most of these children, however, have congenital distal urethral stenosis with secondary spasm of the striated external sphincter rather than bladder neck obstruction.

Lyon and Tanagho (1965) found that the distal urethral ring calibrates at 14F at age 2 and at 16F between the ages of 4 and 10. Even though from the hydrodynamic standpoint, such a stenotic area should not be obstructive, almost all observers agree that dilatation of the ring does relieve symptoms in these children and that it results in cure or amelioration of persistent infection or vesical dysfunction in 80% of cases (Kondo et al, 1994). Tanagho et al (1971) measured pressures in the bladder and in the proximal and mid urethra simultaneously in symptomatic girls and found high resting pressures, some as high as 200 cm of water (normal, 100 cm of water) in the midurethral segment. Attempts at voiding caused intravesical pressures as high as 225 cm of water (normal, 30–40 cm of water) to develop. Under curare, the urethral closing pressures dropped to normal (40–50 cm of water), proving that these obstructing pressures were caused by spasm of the striated sphincter muscle. If the distal urethral ring was treated and symptoms abated, repeat pressure studies showed normal midurethral and intravesical voiding pressures. It seems clear, therefore, that the likely cause of urinary problems in young girls is spasm of the external sphincter and not vesical neck stenosis (Smith, 1969).

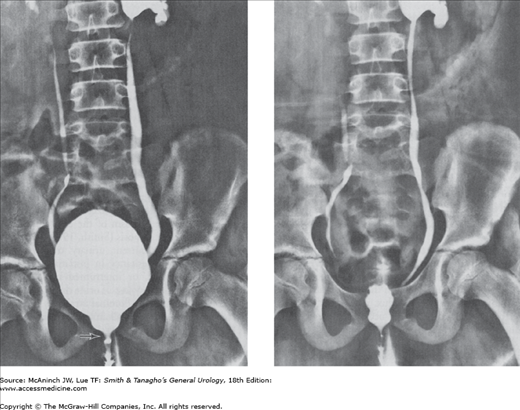

In addition to recurrent urinary tract infections, these patients have hesitancy in initiating micturition and a slow, hesitant, or interrupted urinary stream. Enuresis and involuntary loss of urine during the day are common complaints. Abdominal straining may be required in order to void. Small amounts of residual urine are found, which impair the vesical defense mechanism. A voiding cystourethrogram may reveal an open bladder neck and ballooning of the proximal urethra secondary to spasm of the external sphincter (Figure 42–1).

Figure 42–1.

Distal urethral stenosis with reflux spasm of voluntary urethral sphincter. Left: Voiding cystourethrogram showing bilateral vesicoureteral reflux, a wide-open vesical neck, and severe spasm of the striated urethral sphincter in the mid portion of the urethra (arrow) secondary to distal urethral stenosis. Right: Postvoiding film. The bladder is empty and the vesical neck open, but the dilated urethra contains radiopaque fluid proximal to the stenotic zone. Bacteria in the urethra thus can flow back into the bladder. (Courtesy of AD Amar.)

The voiding cystourethrogram may reveal evidence of the distal ring, but typical findings are not always seen, particularly if the flow rate is slow. Definitive diagnosis is made by bougienage.

Historically, the simplest and least harmful treatment is overdilatation with sounds up to 32–36F). The ring “cracks” anteriorly, with some bleeding. Recurrence of the ring is rare. The results of internal urethrotomy were poor, since incising the urethra along its entire length does not cut the external sphincter (Kaplan et al, 1973).

In the past two decades, it has been recognized that many of these symptoms are due to functional, rather than neurologic or anatomic causes of obstruction. Children must achieve adult patterns of urinary control and disturbances, especially around the time of toilet training. This may cause a variety of symptoms that result from voiding against a voluntarily closed urethral sphincter (dysfunctional voiding). These range from severe functional obstruction with urinary retention, altered bladder anatomy, and vesicoureteral reflux (known as Hinman’s syndrome) to less severe incomplete control of urination. They are often accompanied by bowel symptoms, such as constipation or encopresis. Treatment requires bladder retraining, including psychologic help and biofeedback, as well as restoration of normal bowel habits, including dietary changes and laxatives.

Some children with recurring urinary infection are found to have fused labia minora, which are apt to obstruct the flow of urine, causing it to pool in the vagina. Local application of estrogen cream twice daily for 2–4 weeks usually causes spontaneous separation, with minimal side effects (Aribag, 1975; Leung et al, 2005). Forceful separation or dissection has its advocates (Christensen and Oster, 1971).

It is uncommonly seen as an acquired disease after puberty, caused by genital trauma (sexual abuse, vaginal delivery, surgery, etc) (Kumar et al, 2006). In cultures where “female circumcision” is performed, this may be a relatively common complication (Adekunle et al, 1999).

Acquired Diseases of the Female Urethra

Acute urethritis frequently occurs with gonorrheal (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) or trichomoniasis (Trichomonas vaginalis) infection in women, and it may less commonly occur with infection by Chlamydia trachomatis (approximately 25% of cases are symptomatic). Urinary symptoms are often present at the onset of the disease. Cultures and smears establish the diagnosis. Prompt cure can be achieved with antimicrobial drugs, usually to cover both gonorrhea and chlamydia, such as a combination of intramuscular ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin or doxycycline. Treatment is important, as 40% of women with untreated chlamydia infections will have pelvic inflammatory disease, which may lead to ectopic pregnancy, pelvic pain, and infertility (Simms and Stephenson, 2000).

The detergents in bubble bath and some spermicidal jellies may cause vaginitis and urethritis. Symptoms of vesical irritability may occur (Bass, 1968; Marshall, 1965).

Chronic urethritis is one of the most common urologic problems of females. The distal urethra normally harbors pathogens, and the risk of infection may be increased by wearing contaminated diapers, by insertion of an indwelling catheter, by spread from cervical or vaginal infections, or by intercourse with an infected partner. Urethral inflammation may also occur from the trauma of intercourse or childbirth, particularly if urethral stenosis, either congenital or following childbirth, is present.

The urethral mucosa is reddened, quite sensitive, and often stenotic. Granular areas are often seen, and polypoid masses may be noted just distal to the bladder neck.

The symptoms resemble those of cystitis, although the urine may be clear. Complaints include burning on urination, frequency, and nocturia. Discomfort in the urethra may be felt, particularly when walking.

Examination may disclose redness of the meatus, hypersensitivity of the meatus and of the urethra on vaginal palpation, and evidence of cervicitis or vaginitis. There is no urethral discharge.

When the initial and midstream urine are collected in separate containers, the first glass contains pus and the second does not (Marshall et al, 1970). Ureaplasma urealyticum (formerly called T strains of mycoplasmas) is often identifiable in the first glass. These findings are similar to those of nongonococcal (chlamydial) urethritis in males. Clinically, the presence of white blood cells (leukocytes) in the absence of bacteria on a routine stain or culture suggests nongonococcal urethritis. In other cases, various bacteria (eg, Streptococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli) may be cultured from both the urethral washings and a specimen taken from the introitus.

A catheter, bougie à boule, or sound may meet resistance because of urethral stenosis. Panendoscopy reveals redness and a granular appearance of the mucosa (Krieger, 1988). Inflammatory polyps may be seen in the proximal portion of the urethra. Cystoscopy may show increased injection of the trigone (trigonitis), which often accompanies urethritis.

Differentiation of urethritis from cystitis depends on bacteriologic study of the urine; panendoscopy demonstrates the urethral lesion. Both urethritis and cystitis may be present. Chronic noninflammatory urethritis may be a manifestation of psychic stressors. Patients with anxiety or other temporary or chronic psychologic disorders may present with symptoms that are very suggestive of urethritis. Alternatively, women with long-standing symptoms may have these symptoms as an adult version of childhood voiding dysfunction (see earlier discussion). It is important to understand that chronic dysuria in the absence of a real bacteriologic source is often a manifestation of chronic pelvic pain syndrome (ie, interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome).

Gradual urethral dilatations (up to 36F in adults) are indicated for urethral stenosis; this allows for some inevitable contracture. However, true urethral stenosis is not common in women, and diagnosis should be confirmed by cystoscopy and urethral calibration. If pelvic dysfunction is the underlying issue, calibration under anesthesia will show normal caliber urethra. Immergut and Gilbert (1973) prefer internal urethrotomy (Farrar, 1980). U. urealyticum and chlamydial urethritis usually respond to doxycycline or azithromycin.

After physiologic (or surgical) menopause, hypoestrogenism occurs and atrophic changes take place in the vaginal mucosa, so it becomes dry and pale (Smith, 1972); atrophic vaginitis affects 20–30% of postmenopausal women. This is likely a significant underestimation because women are unwilling to report symptoms due to either embarrassment or lack of knowledge that there are treatments available (Johnston, 2004). Similar changes develop in the lower urinary tract, which arises from the same embryologic tissues as the female reproductive organs. Some eversion of the mucosa about the urethral orifice, from atrophy of the vaginal wall, is usually seen. This is commonly misdiagnosed as caruncle.

Many postmenopausal women have symptoms of vesical irritability (burning, frequency, urgency) and stress incontinence. Dysuria may occur due to urine contact with the inflamed atrophic tissues themselves or because of the increased incidence of urinary tract infections in these women. They may complain of vaginal and vulval itching or tightness, discharge, dyspareunia, and may have bloody vaginal spotting, especially after intercourse.

The vaginal epithelium is dry and pale, with a decrease in the rugae. The mucosa at the urethral orifice is often reddened and hypersensitive; eversion of its posterior lip from atrophy of the urethrovaginal wall is common. Atrophic vaginitis also increases the risk for urinary tract infections, and approximately 10–15% of women older than 60 years have frequent urinary tract infections.

The urine is usually free of microorganisms. The diagnosis can be made by the following procedure: A dry smear of vaginal epithelial cells is stained with Lugol’s solution. The slide is then washed with water and immediately examined microscopically while wet. In hypoestrogenism, the cells take up the iodine poorly and are therefore yellow. When the mucosa is normal, these cells stain a deep brown because of their glycogen content. The diagnosis may also be confirmed by a Papanicolaou smear. Postmenopausal status is associated with a higher vaginal pH, a decrease in vaginal lactobacillus colonization, and increased colonization with E. coli.

Cystourethroscopy may demonstrate a reddened and granular urethral mucosa. Some urethral stenosis may be noted. More commonly, the mucosa at the meatus is reddened, but the remainder of the urethra is quite normal.