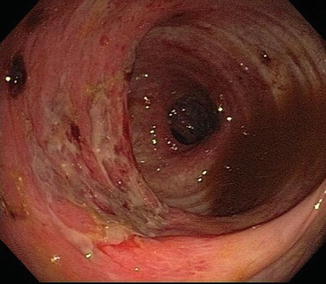

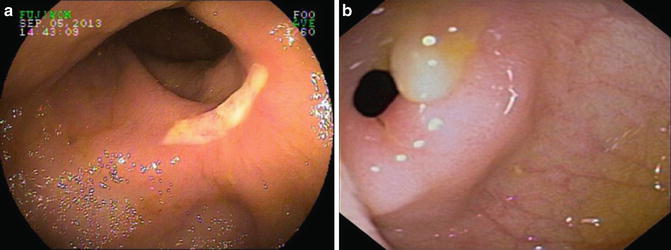

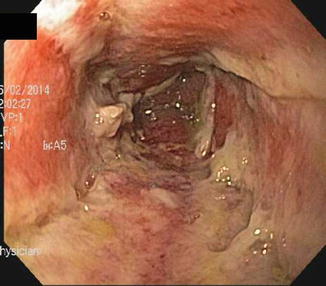

Fig. 10.1

Segmental colitis in the setting of acute diverticulitis

Infectious

A number of infectious colitides can present with bloody or non-bloody diarrhea resembling IBD. These may be due to pathogenic bacteria, viruses, parasites, or fungi. Among these are Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, Shigella, toxigenic Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, Yersinia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI), Neisseria gonorrhea, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes virus, Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium, Isospora, microsporidia, Aspergillus, Cryptosporidium, strongyloides, Candida, Histoplasma, and Toxoplasma [3–12]. These infectious processes should be considered early in patients afflicted with HIV and those with graft versus host disease after transplantation. They should be thought about also in patients who have received antibiotics, imunomodulators or biologic agents—including those with previously documented IBD. Many patients who present with seemingly severe exacerbations of their IBD have acquired a superimposed infectious process, the diagnosis and treatment of which can dramatically alter their course.

Appropriate stool cultures or biopsies are needed to diagnose many of these infections since the macroscopic endoscopic appearance may simulate UC or CD. Clostridium difficile may give rise to creamy plaques of “pseudomembranes,” most often in recto sigmoid but sometimes only in more proximal colon or not at all. Biopsies of inflamed rectal mucosa may reveal the inclusion bodies characteristic of CMV.

Diarrhea is a common symptom in HIV. Although frequently associated with CMV infection (Fig. 10.2), investigation may reveal inflammation of the large intestine without any demonstrable pathogen [17–19]. Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss are typical of this “HIV colitis,” just as seen in IBD. On colonoscopy the mucosal pattern may show diffuse proctocolitis with friability, ulcerations, exudate and edema.

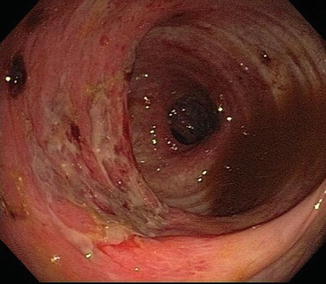

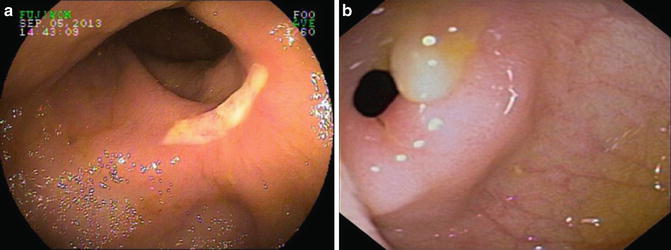

Fig. 10.2

Acute CMV colitis in the setting of HIV infection

Tuberculosis can resemble CD in every respect including biopsy (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4) [20–23]. It most often involves distal ileum and right colon. In fact, prior to the seminal description by Crohn, Ginsburg and Oppenheimer, the entity we now call CD was considered tuberculosis. Now the opposite is true: The diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis can be mistaken for CD, with dire consequences. Consideration of tuberculosis is heightened by travel to or from endemic areas and immunocompromise. Investigation for pulmonary involvement, caseating granulomas, and culturing for M. tuberculosis will eventually reveal the correct diagnosis.

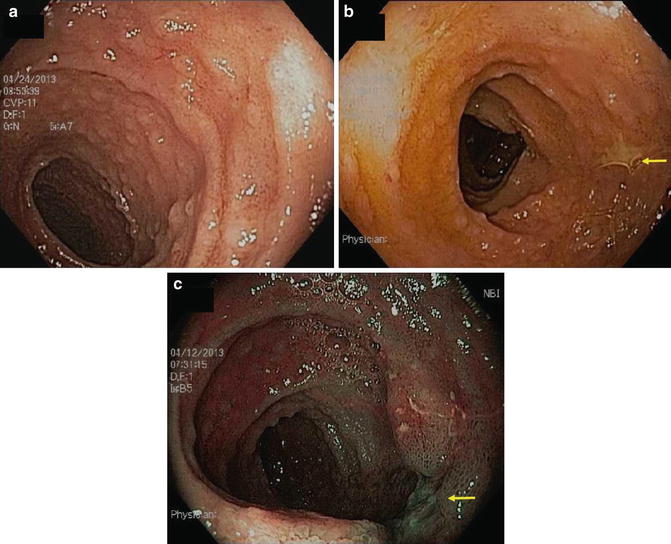

Fig. 10.3

(a) Peyer patch hypertrophy and aphthoid ulcers in patient with ileal tuberculosis. (b) Note larger ulcer visualized with white light and (c) narrow band imaging

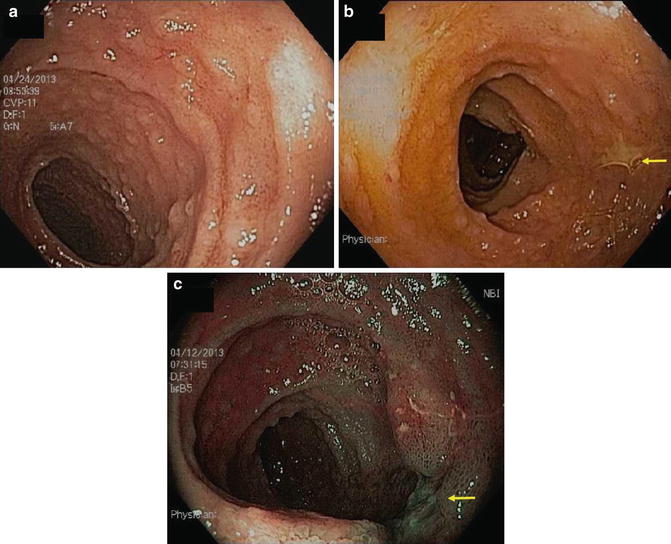

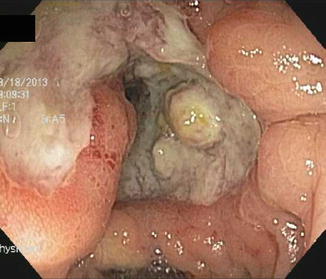

Fig. 10.4

Deep small bowel ulceration related to atypical mycobacterial infection

Vascular

Ischemic colitis typically presents with pain, diarrhea, and bleeding. Unlike UC, it is usually rectal-sparing [24–30]. Like CD, it is segmental, tending to occur at “watershed” transitions of colonic vasculature serving descending-sigmoid colon or around the splenic flexure. The natural course of ischemic colitis is usually spontaneous resolution, but a minority of patients will have a fulminant course progressing to gangrene, necrosis and perforation, or go on to eventual scarring and stricture.

Ischemia is suggested by onset in the elderly or those with hematologic or cardiologic impairment, or those with peripheral vascular disease, recent aneurysm repair or other vascular bypass surgery (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.5

Segmental ischemic colitis following aortic aneurysm repair. Note submucosal hemorrhage, diffuse edema

Endoscopically, ischemia may appear as any other segmental colitis or sometimes as the more diagnostic purplish nodules due to submucosal hemorrhage, corresponding to the “thumb-printing” seen on radiographic studies. Mucosal biopsies often reveal non-specific colitis, but sometimes the more diagnostic mucosal necrosis with cell sloughing.

Iatrogenic

Prominent in this category is the C. difficile colitis described previously that may follow a course of antibiotics [13–16]. There have been reports of C. difficile colitis without antecedant antibiotics administration, perhaps transmitted by health care workers or from antibiotics in consumed food.

Besides antibiotics, other medications can cause gastrointestinal symptoms that simulate IBD. High on this list is the ingestion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [31–33]. These preparations, available without prescription, and often taken liberally for headaches, myalgias, and arthralgias can injure the intestine at many levels. Potential adverse effects on esophagus, stomach and duodenum are better known, but they can cause ulceration and inflammation of other portions of the intestine as well. Sometimes they are dispensed in “enteric coated” or “sustained release” forms that liberate active drug in jejunum, ileum, or colon.

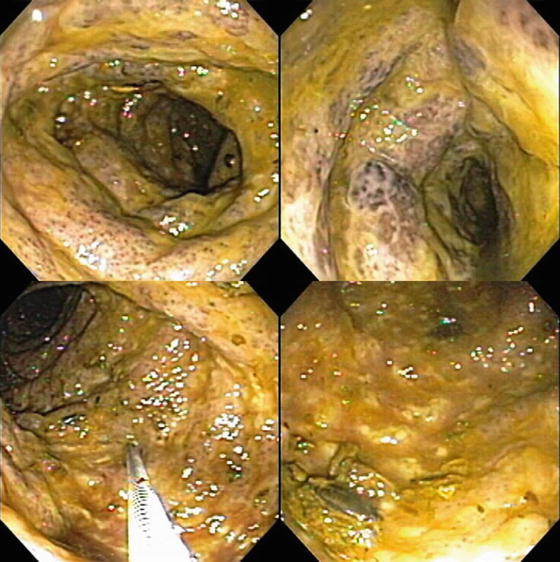

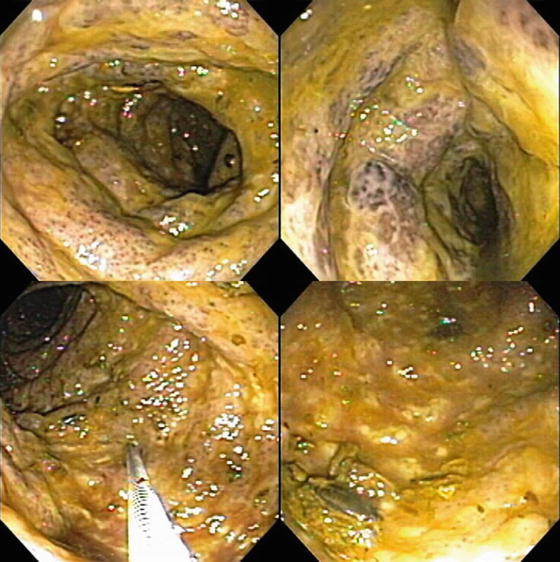

Patients with NSAID-associated enteritis may present with diarrhea and abdominal pain. Examination of small bowel by capsule endoscopy and large intestine by colonoscopy in non-IBD patients has revealed erosions and ulcerations virtually identical to those of CD, often in patients taking NSAIDs who have no gastrointestinal symptoms (Fig. 10.6a, b). Biopsies of these lesions reveal inflammatory cells suggestive of microscopic colitis. These lesions disappear upon discontinuation of the NSAIDs.

Fig. 10.6

(a) NSAID ileal ulcer in patient with multiple additional NSAID-induced small bowel strictures. (b) High-grade ileal stricture as a consequence of chronic NSAID ingestion

NSAIDs have been implicated also in flares of IBD activity in patients with UC and CD. Patients will recognize these symptoms from previous exacerbations of their IBD. Complications may include bleeding, obstruction, perforation, fistulization and stricturing. Physical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic findings are indicative of active IBD and treatment should include elimination of NSAIDs and appropriate escalation of IBD therapy.

A number of medications given topically or systemically can cause inflammation of small or large bowel. These include chemotherapy (Fig. 10.7), enteric-coated potassium, isotretinoin, oral contraceptives, endoscopic cleaning solutions, and phosphosoda-based laxatives [34]. Occasionally and paradoxically, sulfasalazine and mesalamine prescribed to treat mild to moderate colitis can actually produce diarrhea suggestive, wrongly, of active IBD.

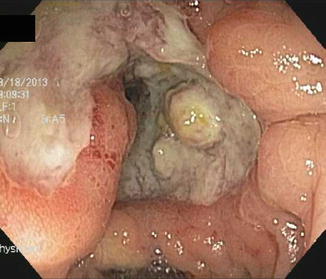

Fig. 10.7

Acute colonic ulceration in patient treated with bevacizumab for breast cancer

Adhesions from prior surgery can cause an obstructive presentation like Crohn’s disease. This can be particularly difficult to differentiate when the surgery was performed for CD. Recurrent Crohn’s commonly occurs around anastomoses. On endoscopy and radiographic imaging, narrowing from adhesions tends to be more localized, as opposed to the longer strictures of recurrent CD. On endoscopy, hypervascularity and circumferential ulceration may be evident at the narrowed anastomosis but the surrounding mucosa appears normal, whereas in Crohn’s there may be the characteristic aphthoid lesions of recurrent IBD. Both anastomotic and CD strictures can be dilated endoscopically using through the scope (TTS) balloons, although this intervention tends to be more successful when the stricturing is just postoperative.

Another post-surgical scenario that can be mistaken for IBD is that in which a portion of the intestine has been bypassed or diverted (Fig. 10.8) [35–37]. Diversion for small bowel CD, in which the Crohn’s segment was left in situ but bypassed had been a popular technique in the mid-twentieth century but is no longer commonly performed for CD. However, temporary diversion of intestinal contents into a colostomy or ileostomy is still performed in multi-staged surgery performed for diverticulitis, cancer, CD, or after colectomy with ileal pelvic pouch. In these instances the bypassed segment of colon or ileum on endoscopic examination prior to closure of the diverting ostomy may appear edematous, friable, and have considerable mucus, raising the specter of IBD. Biopsies may reveal inflammation and lymphoid follicular hyperplasia, just as in IBD. The appropriate and definitive treatment of “bypass enteritis” is to close the diversion and reestablish intestinal continuity.

Fig. 10.8

Bypass colitis with atrophy and marked mucosal friability

Radiation injury to the intestinal tract can be a challenging differential diagnosis from IBD [38–48]. Attempts should be made to elicit a history of prostate or gynecologic malignancy radiation therapy. This history can be relatively recent or very remote. Most of the intestinal tract is protected from radiation by peristalsis, but areas fixed by anatomy (such as the rectum) or by prior surgery remain vulnerable. Thus both small and large bowel may be affected. With rectosigmoid injury patients may have bloody stools, diarrhea, mucoid discharge, urgency and tenesmus, just as in distal UC. With small bowel involvement, patients may have diarrhea, malabsorption, stricturing, fistulization and bacterial overgrowth syndrome, just as can be seen in CD.

Endoscopy of post-radiation colitis may demonstrate mucosal edema, friability and ulceration, just as in acute UC (Figs. 10.9 and 10.10). Often, however, there is a characteristic proliferation of telangiectasias that may be the source of the bleeding. With chronic radiation injury there may be loss of rectal elasticity and even stricturing. Effective therapy of bleeding from the discrete vascular malformations can be delivered via electrocautery or argon plasma coagulation. For more diffuse proctosigmoiditis, topical steroids, mesalamine, or short chain fatty acids can be offered. For refractory distal colitis, application of dilute formalin has been useful but may bring about further loss of compliance and stricturing.

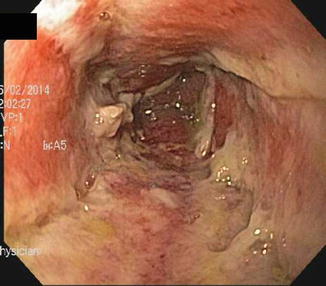

Fig. 10.9

Acute radiation colitis persistent at 6 weeks post irradiation

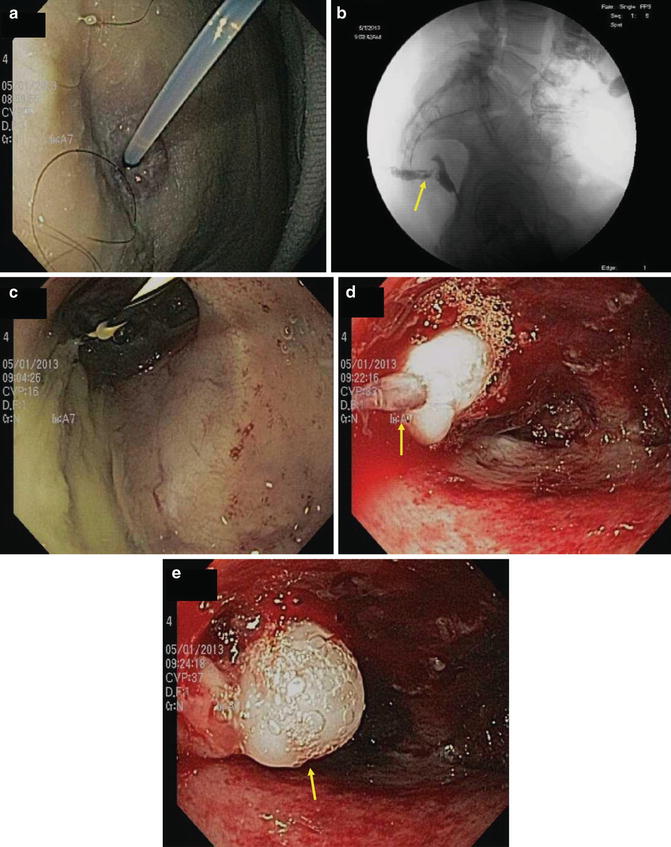

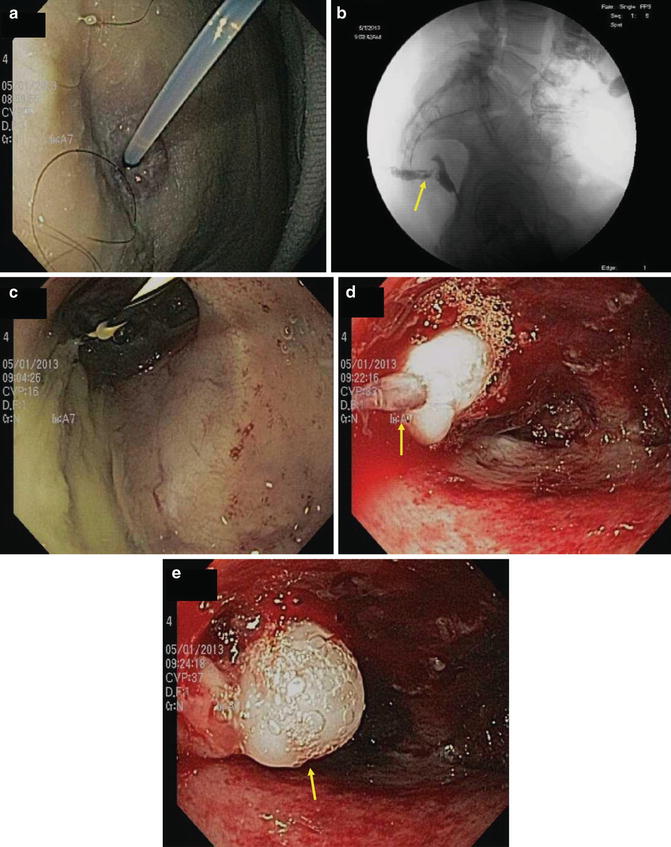

Fig. 10.10

Cutaneous fistula into residual rectum following low anterior resection for cancer followed by irradiation. (a) Note cannula demonstrating (b) fistulous tract radiographically. (c) A guidewire is placed into the rectum. (d) Note multiple radiation telangiectasia following cytology brush abrasion of the tract. (e) The fistula is closed with 2 cc of fibrin glue

Motility

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a misnomer because it is not necessarily solitary or ulcerated [49–55]. The typical history is of chronic constipation, with prolonged straining and use of suppositories or digital manipulation to achieve defecation. It may be associated with rectal prolapse. Patients note blood and mucus associated with tenesmus.

Endoscopic inspection reveals ulceration or localized proctitis with edema, erythema and granularity, just as in idiopathic distal UC. Biopsies of the lesions of SRUS may demonstrate fibroblasts and smooth muscle displaced from muscularis mucosa.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is always in the differential diagnosis of patients with IBD. Symptoms of bowel irregularity, either predominately constipation or diarrhea, bloating, distension, nausea and malaise all overlap with IBD. Significant rectal bleeding, fever, leukoytosis, elevated ESR or CRP, and extraintestinal manifestations are lacking. In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests for IBS, patients usually are evaluated for IBD with the findings of normal colonoscopy, biopsies, and small bowel imaging.

A subpopulation of patients with IBS may be habitual laxative users. They may complain of alternating constipation and diarrhea, bloating and diffuse abdominal pain. Endoscopy reveals normal mucosa, edema, or melanosis after chronic ingestion of anthraquinones such as senna, cascara, or rhubarb laxatives.

Complicating the issue further is the fact that a significant number of patients with documented IBD have coexistent IBS. For these patients relief of symptoms may require simultaneous therapy with antispasmotics and attention to diet and other potential triggers of IBS such as travel, medications, intercurrent illnesses, and stress.

Other Idiopathic Conditions

Microscopic colitis is a diagnostic term encompassing lymphocytic and collagenous colitis [56–60]. Both can present with watery diarrhea and abdominal discomfort. Patients are usually middle-aged or older. Physical examination and blood tests are often normal, although elevations of ESR and CRP are found. The endoscopic appearance may be normal or show edema. Patients are often diagnosed as having IBS of the diarrheal type, but biopsies reveal either a chronic inflammatory mucosal and submucosal infiltrate (lymphocytic colitis) or a prominent subepithelial collagen band (collagenous colitis). Since these findings may be patchy, a number of biopsies from different portions of the colon may be necessary for accurate diagnosis.

The causes of lymphocytic and collagenous colitis have not been established. Some studies have suggested an association with NSAID ingestion [59, 60]. Others have noted the high coincidence of arthritis and autoimmune markers. These mysterious colitides may disappear spontaneously, both clinically and microscopically. Treatment success has been reported with bismuth subsalicylate or with a non-absorbable steroid. In refractory cases, practitioners have had to resort to immunomodulators or even colectomy.

A rare additional idiopathic syndrome mimicking CD is Behcet’s disease [61, 62]. Originally defined by the triad of mouth ulcerations, genital ulcerations, and eye inflammation, this malady can affect any portion of the gastrointestinal tract as well. It presents with abdominal pain, anorexia, rectal bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea.

The mouth ulcerations are described as “aphthous” and the eye lesions include uveitis, just as in CD. The most common gastrointestinal areas affected with ulcerations are distal ileum and cecum. Some patients develop a vasculitis that can lead to bowel ischemia or hepatic vein thrombosis leading to Budd-Chiari syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree