CHAPTER 125 Diseases of the Anorectum

ANATOMY

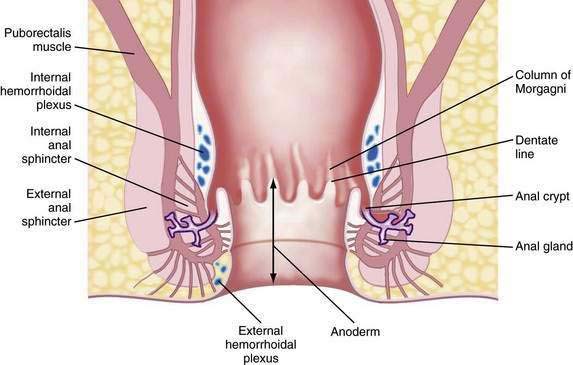

The functional anal canal is 3 to 4 centimeters long, beginning at the top of the anorectal ring (at the puborectalis sling) and extending down to the anal verge (anal orifice).1 The upper anal canal is lined mostly with columnar epithelium, a continuation of the same type of tissue that lines the rectum. Some squamous epithelium starts to be intermixed with the columnar epithelium in the rectum at about one centimeter above the dentate line. This change to squamous epithelium is gradual, and the area 1 to 1.5 cm proximal to the dentate line is termed the transitional zone.2 The dentate line is located in the mid-anal canal and is seen as a wavy line. Distal to the dentate line, the tissue is squamous epithelium, but it is unlike true skin because it has no hair, sebaceous glands, or sweat glands: it is commonly referred to as anoderm. The anoderm is thin, pale, and delicate, with the appearance of shiny, stretched skin. At the anal verge, the epithelium becomes thicker, and hair follicles begin to be seen (Fig. 125-1).3

Embryologically, the dentate line represents the junction between endoderm and ectoderm. Proximal to the dentate line, there is sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation; distally, the nerve supply is somatic.3 Therefore, above the dentate line, pain sensation is negligible; a biopsy can be done painlessly above the dentate line and without the need for local analgesia. Below the dentate line, however, the anoderm is highly sensitive, an important point to note when examining the anal canal or applying hemorrhoidal bands.

The arterial supply of the anal area is from the superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries, which are continuations or branches of the inferior mesenteric, hypogastric, and internal pudendal arteries, respectively. Blood flow is not uniform to the entire circumference of the anus and is relatively less posteriorly. This differential flow is an important factor in the role postulated for ischemia in determining the chronicity of anal fissure.4 The venous drainage from the anal canal is by both the systemic and portal systems. The internal hemorrhoidal plexus drains into the superior rectal veins, which drain into the inferior mesenteric vein and then into the portal vein. The distal part of the anal canal drains via the external hemorrhoidal plexus through the middle rectal and pudendal veins into the internal iliac vein (i.e., the systemic circulation).2

The lymphatic drainage of the anus changes at the dentate line. Proximally, the lymphatic vessels accompany the blood vessels and drain into the inferior mesenteric and periaortic nodes.1–3 Distal to the dentate line, the lymphatics drain into the inguinal nodes. Therefore, inguinal adenopathy can be seen with inflammatory and malignant disease of the lower anal canal.

Immediately proximal to the dentate line, the mucosa appears to have 6 to 14 pleats, called the columns of Morgagni. This configuration represents the funneling of the rectum as it narrows into the anal canal. Located at the base of the columns of Morgagni are anal crypts that lead to small rudimentary anal glands.3 These glands can extend through the internal anal sphincter; if their ducts are blocked, an anal abscess or fistula can develop (see Fig. 125-1).

The muscles surrounding the anal canal are important for maintaining fecal continence. The internal anal sphincter is the thickened continuation of the circular smooth muscle of the rectum. This muscle is involuntary and because it is composed of smooth muscle, it has a black hypoechoic appearance on anal ultrasonography. The internal sphincter ends above the external sphincter.3 The internal sphincter is important for passive continence, but partial division of the internal sphincter is possible without causing significant fecal incontinence. Division in the anterior or posterior position, however, can lead to stool leakage by creating an oval-shaped configuration in the distal anal canal, termed a keyhole deformity because the shape was reminiscent of the opening for the key in old-fashioned door locks.

The external anal sphincter is under voluntary control and is composed of a sheet of skeletal muscle arranged as a tube surrounding the internal sphincter. It appears as a broad cylinder with mixed echogenicity on anal ultrasound. Proximally, the external sphincter is fused with the puborectalis muscle, and distally, it ends slightly past the internal sphincter.1,3 Therefore, a groove can be palpated between the internal sphincter and external sphincter on digital examination, which is referred to as the intersphincteric groove. The puborectalis is U-shaped and forms a sling that passes behind the lower rectum and attaches to the pubis. Therefore, it is prominent laterally and posteriorly but absent anteriorly. The anorectal ring is palpable at the top of the anal canal, where the canal meets the rectum. It is composed of the puborectalis and the upper external and internal sphincters. The nerve supply to the external sphincter and puborectalis muscle is from the inferior rectal branch of the internal pudendal nerve (S2, S3, S4) and also from fibers of the fourth sacral nerve.1,3

EXAMINATION OF THE ANUS AND RECTUM

INSPECTION

Traction applied laterally to each side of the anal orifice with a gauze pad allows eversion of the distal anus for further inspection. This technique is particularly helpful in viewing a fissure without causing undue pain (Fig. 125-2). Some examiners stroke the perianal skin with a cotton-tipped applicator to look for reflex contraction of the anal muscles (anal wink, anocutaneous reflex) or check perianal sensation with a pinprick; these maneuvers give a crude determination of sphincter innervation and are important in evaluating for sensory neuropathies. The nearby skin of the buttocks, perivaginal region, base of the scrotum, and up to the tip of the coccyx should be viewed. Adenopathy in the inguinal region may be seen when certain infectious or neoplastic lesions are found distal to the dentate line.

ENDOSCOPY

The decision to perform endoscopy depends on the findings on history and physical examination. Endoscopy usually is necessary for the evaluation and exclusion of organic disease in patients with fecal incontinence, constipation, unexplained anal pain,5 anemia, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding.

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

The flexible sigmoidoscope is simply a shorter version of a colonoscope, measuring 60 cm in length. Most endoscopists use a gastroscope for sigmoidoscopy because it is thinner, better tolerated by the patient than a sigmoidoscope or colonoscope, and easier to maneuver. One to two enemas are given before the examination and sedation typically is not used, which is the reason patients who have undergone both colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy report that the latter was more difficult.6 The goal is to examine the left colon, which should be reached at least 80% of the time.7 Lesions can be biopsied, but the presence of polyps mandates full colonoscopy after a bowel preparation to exclude synchronous polyps or cancer. The use of electrocautery and argon plasma coagulation should be avoided during sigmoidoscopy, even if enemas have just been given and the preparation appears optimal, because intracolonic bowel explosions have occurred from ignition of bowel gas that has passed from the stool-containing proximal colon distally to the operative site.8

HEMORRHOIDS

Hemorrhoids are perhaps the most misunderstood anorectal problem for patients and physicians alike. In clinical practice, patients use the term hemorrhoid to describe almost any anorectal problem, from pruritus ani to cancer.9 In fact, hemorrhoids are a normal part of human anatomy,10,11 in contrast to hemorrhoidal disease, which is manifested by prolapse, bleeding, and itching.10 Hemorrhoids are dilated vascular channels located in three fairly constant locations: left lateral, right posterior, and right anterior. Internal hemorrhoids originate above the dentate line and are covered with columnar or transitional mucosa. External hemorrhoids are located closer to the anal verge and are covered with squamous epithelium. Traditionally, internal hemorrhoids are classified into four grades: first-degree hemorrhoids, which bleed with defecation; second-degree hemorrhoids, which prolapse with defecation but return spontaneously to their normal position; third-degree hemorrhoids, which prolapse through the anal canal at any time, but especially with defecation, and can be replaced manually; and fourth-degree hemorrhoids, which are prolapsed permanently.11 Although the exact incidence of hemorrhoidal disease is unknown, it is thought to be present in 10% to 25% of the adult population.12

INTERNAL HEMORRHOIDS

Symptoms and Signs

It is speculated that internal hemorrhoids become symptomatic when their supporting structures become disrupted and prolapse of the vascular cushions occurs.13 Hemorrhoids occur more commonly in people with constipation who have hard, infrequent stools.14 They also can occur in patients who have frequent loose stools or if prolonged periods of time are spent sitting on the toilet, leading to vascular congestion. Bleeding is typically painless and the patient describes bright red blood usually seen on the toilet tissue, dripping into the toilet bowl, or streaking the outside of a hard stool. If the bleeding is more substantial, the blood can accumulate in the rectum and be passed later as dark blood or clots.11 If the patient has chronic hemorrhoidal prolapse, blood or mucus might stain the patient’s underwear, and the mucus against the anal skin might lead to itching.10

Treatment

Treatment is based on the grade of the hemorrhoids. Grade 1 and some early grade 2 internal hemorrhoids usually respond to manipulation of the diet, along with avoidance of medications that promote bleeding, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A high-fiber diet, with 20 to 30 g of fiber daily introduced gradually into the diet, should be accompanied by six to eight glasses of nonalcoholic, noncaffeinated fluid daily. Patients are encouraged to read the package regarding the amount of fiber per serving; for instance, a bowl of raisin bran cereal can have eight grams of dietary fiber per serving whereas a similar portion of corn flakes has only one gram.15 Fiber supplementation with psyllium or hydrophilic colloid may be added to achieve the optimal amount of daily fiber, if the patient’s daily dietary fiber is insufficient. In my experience, patients who can achieve adequate dietary fiber intake without supplements have better long-term relief of hemorrhoidal disease with dietary change than those who need daily supplementation.

Patients are urged to avoid straining during defecation and reading while on the toilet. Excessive scrubbing of the anus when showering or bathing or excessive wiping after a bowel movement is discouraged. Most over-the-counter agents are not efficacious, even though many patients report some relief of their symptoms with use of these products.14 Sometimes a stool softener such as docusate sodium or a lubricant such as mineral oil can be prescribed if the stool is hard and does not respond to increased intake of fiber and fluid; laxatives and enemas rarely are needed.15 Even patients who require more-aggressive treatment of their hemorrhoids should be advised to increase their dietary fiber and fluids and to avoid straining during defecation to prevent recurrence after treatment.

Sclerosing Agents

Injection therapy for hemorrhoids has been practiced for more than 100 years. The goal is to inject an irritant into the submucosa above the internal hemorrhoid at the anorectal ring (the area that does not have somatic innervation) to create fibrosis, tack down the hemorrhoid and prevent hemorrhoidal prolapse.16 Usually less than one milliliter of sclerosant is needed to create a raised area. Many substances have been used, but sterile arachis oils containing 5% phenol are the most popular.16 This approach usually is advocated for first- and second-degree hemorrhoids.

Sclerotherapy can produce a dull pain for up to two days after injection. A rare but severe complication is life-threatening perineal sepsis, which can occur three to five days after injection and usually is manifested by any combination of perianal pain or swelling, watery anal discharge, fever, leukocytosis, and other signs of sepsis. Prompt surgical intervention and intravenous antibiotics are mandatory.16,17 Approximately 75% of patients with second-degree hemorrhoids improve after injection therapy.18

In patients with active acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), injection therapy may be favored over surgical treatments because of concerns about the patient’s poor overall general condition. There also may be problems with wound healing for these patients, but successful treatment of second-, third-, and fourth-degree hemorrhoids without complications has been reported in patients with AIDS,19 some of whom did require repeat treatment to manage persistent symptoms.

Rubber Band Ligation

Rubber band ligation (RBL) has become the most common office procedure for the treatment of second- and third-degree hemorrhoids.20 Generally, this approach cannot be used with first-degree hemorrhoids, because there is insufficient tissue to pull into the bander; this treatment is not appropriate for fourth-degree hemorrhoids.18

Rubber bands are applied to the hemorrhoidal complex and rectal mucosa just proximal to the internal anal cushion. To avoid severe pain, bands are never placed below the dentate line, which is innervated by somatic fibers. The number of bands that can be safely placed in one setting remains controversial. Several studies have shown that triple RBL is safe and effective at one sitting,20,21 but many authorities believe that the severity of pain and risk of complications are less if one band is applied per visit. I typically place a single band at the first visit, and if that is well tolerated, I place two bands during the next and subsequent visit. Most grade 2 or 3 hemorrhoids can be managed successfully with two or three RBL procedures.

Major complications from RBL include bleeding, sepsis, cellulitis, and death. Bleeding when the band and necrotic hemorrhoidal tissue comes off four to seven days after application may be severe and even life-threatening; severe bleeding occurs in about 1% of patients21 and usually can be tamponaded by placing a large-caliber Foley catheter in the rectum, filling the balloon with 25 to 30 mL or more of fluid, and pulling the balloon tightly against the top of the anal ring. If this approach fails, epinephrine can be injected at the bleeding site, but sometimes a suture is required to stop the bleeding.

A more serious complication is sepsis. There have been five recorded deaths, two additional patients with life-threatening sepsis, and three cases of severe pelvic cellulitis following RBL of hemorrhoids.17 The onset of sepsis usually is two to eight days after RBL in otherwise healthy people. New or increasing anal pain, sometimes radiating down the leg, or difficulty voiding may be the first indications of a life-threatening infection. Immediate intravenous antibiotics and surgical débridement are required.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy freezes tissue, thereby destroying the hemorrhoidal plexus. Once a popular treatment, its use has declined because of the profuse, foul-smelling discharge resulting from tissue necrosis. The procedure also can be painful, and healing can be prolonged.22

Infrared Photocoagulation

Infrared photocoagulation uses infrared radiation to coagulate the tissue, leading to fibrosis. The device is applied for 1.5 seconds in two or three sites proximal to the hemorrhoidal plexus. Reported results for first- and second-degree hemorrhoids are as good as those reported for RBL or sclerotherapy.18 One study reported a 10% relapse rate at three years in patients who had third-degree hemorrhoids and were treated with RBL at recurrence.23 Pain and other complications are rare with infrared photocoagulation. This technique also can be useful when there is a small amount of residual friable hemorrhoidal tissue that cannot be banded, either because there is too little tissue to be incorporated into the band or the tissue is too distal to be safely banded without causing discomfort. In my opinion, this technique generally is less effective than RBL.

Surgical Therapy

Based on the common finding of increased resting anal canal pressure in patients with hemorrhoids,24 methods to reduce internal anal sphincter pressure in these patients, including internal sphincterotomy and manual dilation of the anus (Lord’s procedure) had been advocated in the past; today, these procedures are mainly of historical interest. One study of the Lord procedure to treat second- and third-degree internal hemorrhoids with a median follow-up of 17 years found a nearly 40% recurrence rate and a 52% rate of incontinence.25 Lateral internal sphincterotomy occasionally is performed if patients are found to have both a fissure and extensive hemorrhoids at the time of surgery for hemorrhoids.

Hemorrhoidectomy is the surgical procedure of choice for fourth-degree and some third-degree hemorrhoids and rarely is needed for first- or second-degree hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoidectomy can be done with local, regional, or general anesthesia. Whether the edges of the mucosa are closed or left open after excision of the hemorrhoidal tissue is a matter of preference, because results and severity of postoperative pain are similar with both approaches.26 In one of the few long-term studies of hemorrhoidectomy, recurrent hemorrhoids were found in 26% at a median follow-up of 17 years,25 but only 11% of patients needed an additional procedure.

Postoperative pain is the major drawback of hemorrhoidectomy. In an effort to reduce postoperative pain, topical and oral metronidazole have been used with success, although the mechanism of this action is not known.27 Additionally, a new procedure was introduced in 1998 by Longo,28 in which a circular stapler is used to fix the anal cushions in their correct positions. The mucosa is excised circumferentially just above the anorectal ring, thereby interrupting the vascular supply to the cushion (Fig. 125-3). This procedure is called the procedure for prolapse of hemorrhoids (PPH) or stapled hemorrhoidopexy. It is used for third- and fourth-degree hemorrhoids. Results of the randomized multicenter U.S. experience, which compared PPH with traditional excisional hemorrhoidectomy, showed that PPH-treated patients experienced significantly less pain.29 Another study comparing PPH with RBL found patients reported more pain and an increased risk of postoperative bleeding with PPH; however, more patients in the RBL group required excisional hemorrhoidectomy for persistent symptoms.30

PPH can have significant postoperative complications, of which bleeding and urinary retention are most common.29 Severe persistent postoperative pain occurs in one third of patients and may be related to placing the staple line too close to the dentate line.31 Additionally, defecation urgency can be persistent in up to 28%. Perhaps the most feared complication is pelvic sepsis leading to death.32 Several studies analyzing the long-term results of the prospective randomized studies comparing excisional hemorrhoidectomy and PPH suggest a higher rate of recurrent hemorrhoidal symptoms in the PPH group.33–34 Further long-term studies are needed to define the durability of the PPH procedure.

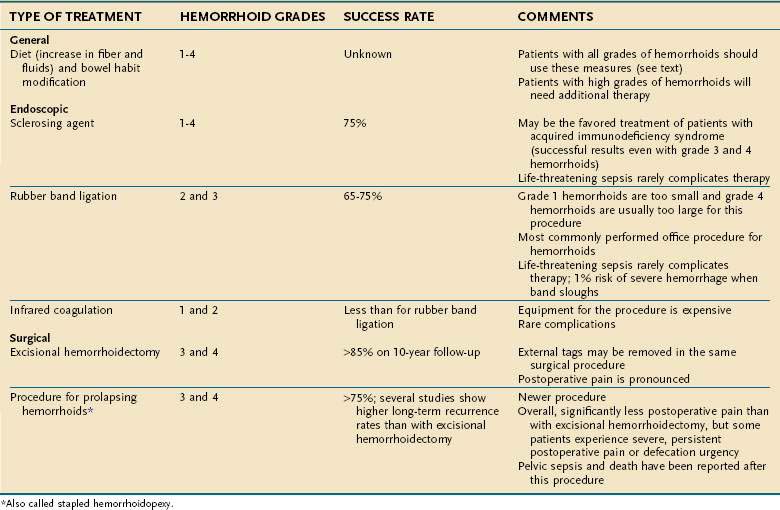

Table 125-1 summarizes the treatment options for internal hemorrhoids.

EXTERNAL HEMORRHOIDS AND ANAL TAGS

Symptoms and Signs

External hemorrhoids can be associated with acute pain from thrombosis.13 The level of pain is variable, but patients might notice a rapidly increasing throbbing or burning pain accompanied by a new lump in the anal region. Sometimes the lump has a bluish discoloration caused by the clot. With time, a small area of necrosis can form over the lump, followed by extrusion of the clot, with relief of the pain.

Treatment

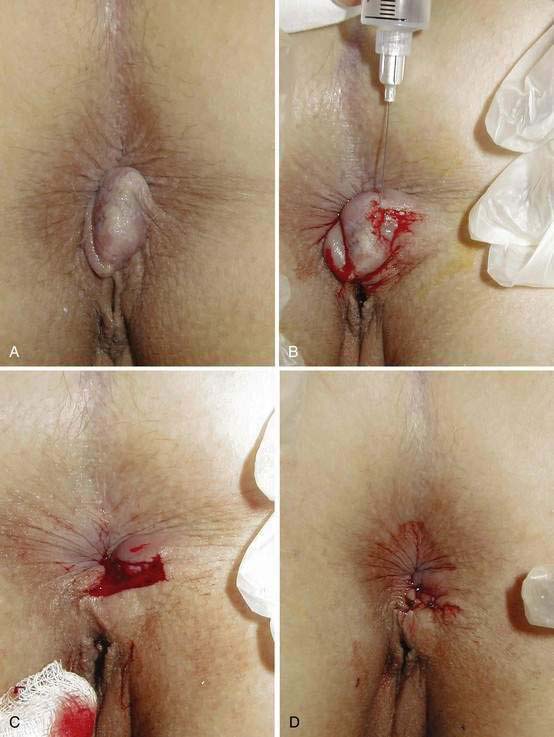

Treatment of thrombosed hemorrhoids depends on the associated symptoms. With time, the pain associated with the acute thrombosis subsides. If the patient has minimal or moderate pain, sitz baths and analgesics are prescribed. For severe pain, the clot is removed under local anesthesia. Because of the high rate of recurrence with simple enucleation alone, most surgeons recommend excising the entire thrombosis and overlying skin. This procedure also can be done in the office with scissors and local anesthesia (Fig. 125-4).35 The skin edges may be closed or left open to heal by second intention.

Another successful therapy has been topical application of 0.3% nifedipine cream.36 It is speculated that the success of nifedipine cream in reducing pain from thrombosed hemorrhoids results from its anti-inflammatory and smooth muscle-relaxing properties. Its use can preclude the need for surgery.

Special Considerations

Large, edematous, shiny perianal skin tags should alert the physician to the possibility of Crohn’s disease. These tags can have a waxy bluish discoloration (Fig. 125-5), are often tender, and are best described as “funny looking.” Careful history taking for symptoms of Crohn’s disease is indicated, and further testing is needed if there is any suspicion that the tags are other than ordinary. Surgical excision of these Crohn’s disease tags is to be avoided in almost every situation, because after surgery the patient usually is left with unhealed anal ulcers.

Figure 125-5. Anal skin tags associated with perianal Crohn’s disease. Note the waxy bluish appearance of the tags.

Patients who are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) usually are treated as if they do not carry HIV, unless their immune status is significantly compromised. Previously mentioned was the use of sclerotherapy in this population.19 In another study of 11 HIV-positive men with a mean CD4+ count of 420 cells/mm3 and a mean follow-up of six months, no complications occurred after RBL of hemorrhoids, and symptoms improved in all.37

ANAL FISSURE

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of a chronic anal fissures is unknown. Using laser Doppler flowmetry, it has been shown that the posterior area of the anoderm is less well perfused than other areas of anoderm. There is speculation that increased tone in the internal sphincter muscle further reduces the blood flow to this area, especially in the posterior midline.4 Based on these findings, fissures are thought to represent ischemic ulceration.38 Trauma during defecation, especially with passage of a hard stool or explosive diarrhea, is believed to initiate formation of a fissure.