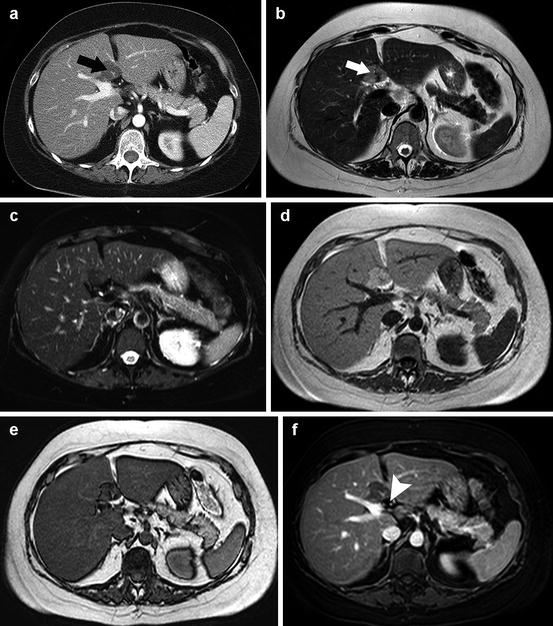

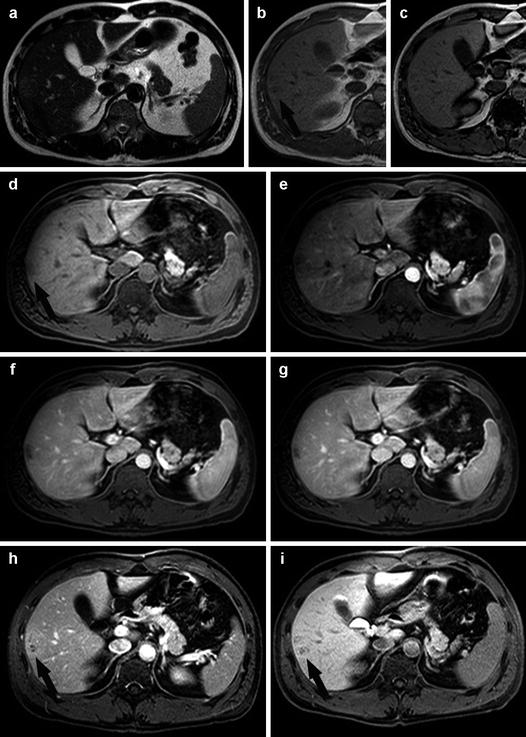

Fig. 7.1

Atypical hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient with chronic liver disease and a previous hepatic resection for HCC. At US screening, an isoechoic nodule with an hypoechoic halo (a) was detected, and the patient was referred for MRI with hepatocyte-specific contrast agent (Gd-EOB-DTPA) to characterize the lesion. On T2-weighted images, (b) the nodule is slightly hyperintense with blurred margins (black arrow), probably due to peritumor edema; on chemical shift imaging, the lesion presents a dropout of the signal in the opposite-phase sequences (c, in phase; d, out of phase), as being predominantly composed of intracellular fat. At the dynamic study (not shown), the tumor is hypovascular. On hepatobiliary phase T1-weighted images without fat suppression, the lesion is isointense (black arrow, e) simulating the presence of functional hepatocytes; however, the fat-saturated sequence (f) reveals marked hypointensity of the nodule, consistent with fat infiltration and loss of hepatocellular function. In relation to a nontypical imaging pattern and to the clinical history, the patient was referred to fine-needle biopsy of the lesion that resulted a moderately differentiated HCC at histology

7.2 Benign Lesions That May Mimic Liver Neoplasm

7.2.1 Liver Abscess

Liver abscess es (Fig. 7.2) present as single or multiple lesions of variable sizes, even coalescing. Imaging is fundamental for diagnosis and may eventually guide percutaneous drainage. The use of intravenous contrast is vital since hepatic abscesses have a typical appearance. On multiphasic CT, they consist in centrally hypodense (due to purulent necrosis) lesions frequently associated to peripheral enhancing rims; the core is usually hypovascular. Thin-section imaging during the portal-venous phase can optimize detection of small lesions and air bubbles [15]. Fungal abscesses typically manifest as microabscesses that involve the liver, spleen, and occasionally kidneys. They are usually multiple, small (2–20 mm), round, and hypodense with or without peripheral enhancement. A peripheral hypodense zone representing edema may be seen, along with septations and fluid-debris levels [15].

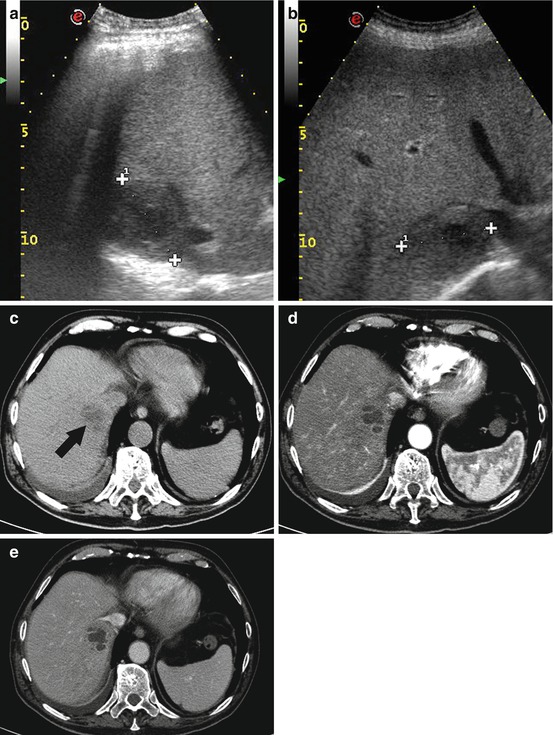

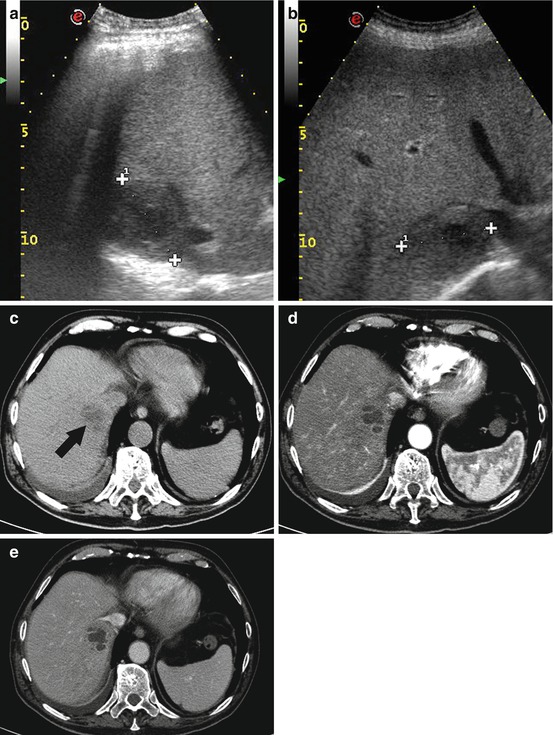

Fig. 7.2

A 72-year-old man with a hepatic pyogenic abscess. The patient was examined with liver ultrasound for abdominal pain in the upper right quadrant. A heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion with ill-defined margins and hypoechoic core was noted (a, b). A contrast-enhanced CT scan was requested to better investigate the lesion and to rule out the presence of source of infection or malignancies. On an unenhanced CT scan, (c) the lesion is heterogeneously hypodense (black arrow); a peripheral rim enhancement is seen on the arterial and portal phase images (respectively d and e) after administration of contrast media. At the dynamic study, the lesion shows also the typical “cluster sign,” consistent with abscess; no source of infection (e.g., diverticulitis, cholecystitis) was found. Due to the small dimensions of the lesions, no percutaneous drainage was indicated and the patient assumed antibiotic therapy with complete remission of symptoms

US offers a prompt evaluation of the probable abdominal source of infection (cholecystitis, appendicitis, or diverticulitis) and the biliary tract [6]. At US liver abscesses are usually solid lesion with variable echogenicity acutely, but with maturation, pus formation, necrosis, and liquefaction, they tend to become hypoechoic with distinct margins [17]; in case of gas-producing organisms, US shows intense echogenicity with posterior reverberations [5]. At color Doppler sonography, liver abscesses are centrally avascular, usually with some peripheral flow corresponding to areas of contrast enhancement at CEUS [4].

At MRI liver abscesses present central low T1w signal and intermediate to slightly hyperintense heterogeneous T2w signal; the abscess wall enhances on the arterial phase and generally intensifies on the interstitial phase on postcontrast T1w sequences. Perilesional enhancement may be seen due to hyperemic inflammatory reaction in the adjacent liver [16]. Fungal abscess es appear as low signal foci on gadolinium-enhanced T1 images, characterized by minimal appreciable rim enhancement. The absence of granulation tissue in the capsule is most likely related to the neutropenia of immunocompromised patients [15].

Echinococcal abscess es (hydatid cysts) present as spherical cystic lesions, with fibrous rims and well-defined margins. Typically, there is little tissue reaction, unless the cyst breaks and leaks fluid that can induce a marked inflammatory reaction: heterogeneous high T2 and low T1 signal is due to internal proteinaceous fluids. The enhancing wall, seen on postcontrast T1w images, is usually thin. Coarse calcifications of the wall are present in 50 % of cases and are better identified with CT. Daughter cysts or septations are found in approximately 75 % of patients [12].

Tuberculosis is globally the most common cause of infectious hepatic granulomas that present with variable signal intensity on basal T1w and T2w sequences and minimal enhancement. Lesions tend to involve the portal triad and are associated to enlarged portal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes [16].

7.2.2 Other Inflammatory Masses

Focal hypereosinophilic infiltration is a focal hepatic lesion caused by eosinophil-related tissue damage, associated with various conditions such as parasitic infections, allergic reactions, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and tumors. It is characterized by indistinct margin and a nonspherical shape. At MRI a focal hypereosinophilic infiltration mass is hypointense on T1- and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The dynamic imaging is characterized by poor enhancement on the arterial phase with homogeneous enhancement on portal-venous phase images. A predominant hypointensity characterizes the hepatobiliary phase of liver-specific contrast agents at MRI [8].

Inflammatory pseudotumor (Fig. 7.3) is a very rare entity characterized by an inflammatory infiltrate usually of undetermined nature, composed of plasma cells, histiocytes, and fibrosis [3, 4]. It presents with nonspecific clinical symptoms (fever, weight loss, and leukocytosis) or may be detected incidentally. Due to its rarity and its atypical imaging features, a percutaneous biopsy should be performed to rule out the presence of malignancy.

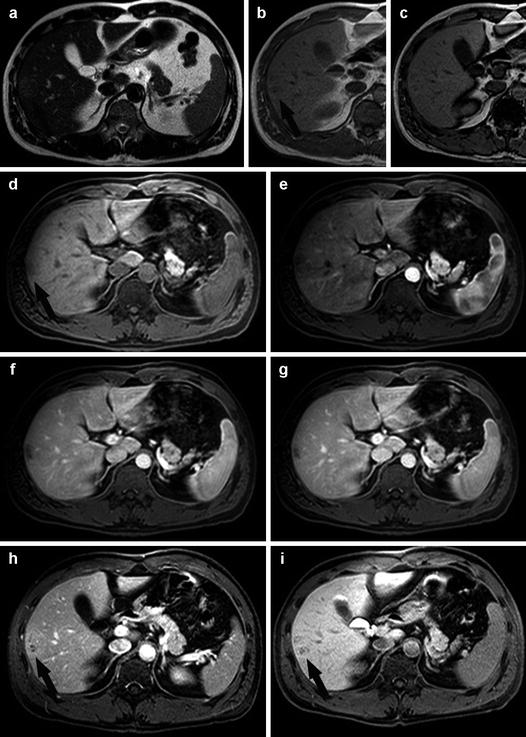

Fig. 7.3

Inflammatory pseudotumor in a young Asian male. On the pre-contrast T2-weighted image, (a) a slightly hyperintense lesion in the right lobe is visible (black arrow). On both the corresponding pre-contrast T1-weighted in-phase (arrow, b) and out-of-phase (c) images, the lesion is hypointense with no signal variation due to chemical shift artifact. The tumor is hardly seen on basal T1w images (black arrow, d); some early peripheral enhancement (e) is seen after bolus injection of contrast agent, reflecting the cellular components and inflammatory changes within the lesion. However, the lesion shows poor vascularity with slow accumulation of contrast agent (during portal and venous phases, respectively f and g) in probably fibrotic components that become hyperintense in T1 fat-suppressed images (arrow, h) acquired 5 min post-contrast injection. Hepatobiliary phase imaging (i) reveals a hypointense area representing the absence of functioning hepatocytes within the lesion (arrow). The patient underwent percutaneous fine-needle biopsy that confirmed the diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumor

7.3 Miscellanea

7.3.1 Post-traumatic Lesions

Surgery and trauma are the two most common causes of intrahepatic bleeding. On CT, the appearance of an intrahepatic hemorrhage changes progressively with time. In an acute or subacute setting, hemorrhage has a higher attenuation value than pure fluid due to the presence of aggregated fibrin components. In chronic cases, a hematoma has an attenuation identical to that of pure fluid. Because of the paramagnetic effect of methemoglobin, MRI is even more suitable than CT for the detection and characterization of hemorrhage. A subacute hematoma appears as a heterogeneous mass with pathognomonic high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images [12].

Biloma s result from rupture of the biliary system, which can be spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic. Extravasation of bile into the liver parenchyma generates an intense inflammatory reaction, thereby inducing formation of a well-defined pseudocapsule. At both CT and MR imaging, a biloma usually appears as a well-defined or slightly irregular cystic mass without septa or calcifications [12].

7.3.2 Focal Steatosis and Focal Fatty Sparing Areas

Focal (Fig. 7.4) or multifocal (Fig. 7.5) steatosis is a common finding that can present with a pseudotumor hyperechoic appearance at US, hypodense on CT; however, its distribution is quite typical with involvement of periportal and periligamentous spaces, subcapsular areas, and gallbladder fossa [18]. On the contrary, focal fatty sparing areas in a steatotic liver appear as a hypoechoic lesion at US, usually with a distribution pattern similar to that of focal fatty infiltration. The topography of these lesions seems to be related to aberrant portal or venous drainage, thus justifying the similar distribution pattern of these apparently opposed conditions [18]. Other conditions in which hepatic steatosis may be observed with atypical distribution and require particular attention are the omental packing (usually posttraumatic or postsurgical) and the presence of (maybe unsuspected) metastases that alters peritumor blood flow. On CT the diagnosis of focal steatosis or focal fatty sparing is easy: the accumulation of fat in the liver proportionally decreases x-ray attenuation. However, the most accurate technique to correctly characterize focal steatosis or focal fatty sparing and to definitely rule out the presence of metastatic disease is MRI with the chemical shift imaging technique, based on the acquisition of in-phase and opposed-phase T1-weighted images [18].