Medical Renal Disease—Overview

Medical renal diseases are those that involve principally the parenchyma of the kidneys. Hematuria, proteinuria, pyuria, oliguria, polyuria, pain, renal insufficiency with azotemia, acidosis, anemia, electrolyte abnormalities, and hypertension may occur in a wide variety of disorders affecting any portion of the parenchyma of the kidney, the blood vessels, or the excretory tract.

A complete medical history and physical examination, a thorough examination of the urine, and blood and urine chemistry examinations as indicated are essential initial steps in the workup of any patient.

The family history may reveal disease of genetic origin, for example, tubular metabolic anomalies, polycystic kidneys, unusual types of nephritis, or vascular or coagulation defects that may be essential clues to the diagnosis. First-degree relatives of patients with diabetic renal disease have an enhanced risk of end-stage renal disease, inherited independently of diabetes mellitus.

The past personal history should cover infections, injuries, and exposure to toxic agents, anticoagulants, or drugs that may produce toxic or sensitivity reactions. A history of diabetes, hypertensive disease, or autoimmune disease may be obtained. The inquiry may also elicit symptoms of uremia, debilitation, and the vascular complications of chronic renal disease, but often, the patient is asymptomatic and the diagnosis of renal disease is made incidentally on abnormal laboratory findings.

Pallor, edema, hypertension, retinopathy (either hypertensive or diabetic changes), or stigmas of congenital and hereditary disease may be detected.

Examination of the urine is the essential part of any investigation of renal disease.

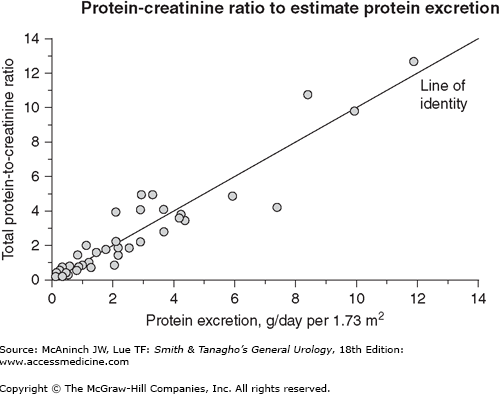

Proteinuria of any significant degree (2–4+) is suggestive of medical renal disease (parenchymal involvement). Formed elements present in the urine additionally establish the diagnosis. Significant proteinuria occurs in immune-mediated glomerular diseases or disorders with glomerular involvement such as diabetes mellitus, myeloma, or amyloidosis. Interstitial nephritis, polycystic kidneys, and other tubular disorders are not usually associated with significant proteinuria. To better quantify the degree of proteinuria, one could either collect a 24-hour urine sample or use a spot urine protein to creatinine ratio (measured in milligrams of protein/mg creatinine) as a surrogate (see Figure 33–1).

Figure 33–1.

This graph illustrates the relation between total 24-hour urinary protein excretion and the total protein-to-creatinine ratio (mg/mg) determined on a random urine specimen. Although there appears to be a close correlation, there can be wide variability in 24-hour protein excretion at a given total protein-to-creatinine ratio. At a ratio of 2, for example, 24-hour protein excretion varied from 2 to almost 8 g/d. (Data from Ginsberg JM et al: N Engl J Med 1983;309:1543.)

Red blood cell casts point to glomerulonephritis. If red blood cell (erythrocyte) casts are not present, microscopic hematuria may or may not be of glomerular origin. Phase contrast microscope study may reveal dysmorphic changes in the erythrocytes present in the urine in patients with glomerular disorders.

Tubular cells showing fatty changes occur in degenerative diseases of the kidney (nephrosis, glomerulonephritis, autoimmune disease, amyloidosis, and damage due to toxins such as lead or mercury).

These types of casts result from degeneration of cellular casts. They are nondiagnostic of a specific renal disorder but do reflect an inflammatory condition in the kidneys.

Abnormal urinary chemical constituents may be the only indication of a metabolic disorder involving the kidneys. These disorders include diabetes mellitus, renal glycosuria, aminoacidurias (including cystinuria), oxaluria, gout, hyperparathyroidism, hemoglobinuria, and myoglobinuria.

Roentgenographic, sonographic, and radioisotopic studies provide information about the size, structure, blood supply, and function of the kidneys.

Renal biopsy is a valuable diagnostic procedure. The technique has become well established, providing sufficient tissue for light and electron microscopy and for immunofluorescence examination. Relative contraindications for percutaneous kidney biopsy may include the patients with a congenitally solitary kidney, severe malfunction of one kidney even though function is adequate in the other, bleeding diathesis, and an uncooperative patient. Poorly controlled blood pressure (systolically >160 or diastolically >100 mm Hg) should be controlled prior to performing an invasive procedure such as renal biopsy.

Clinical indications for renal biopsy, in addition to the necessity for establishing a diagnosis, include the need to determine prognosis, to follow progression of a lesion and response to treatment, to confirm the presence of a generalized disease (autoimmune disorder, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis), and to diagnose renal dysfunction in a transplanted kidney. Ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) guidance provides a more effective biopsy result. More recently, laparoscopic approach has been used by some urologists.

With the increasing demand for renal biopsies in patients with a bleeding diathesis, especially in those with concomitant liver dysfunction, a transjugular approach has been advocated. However, the success of this procedure is highly dependent on the experience of the center and operators, and diagnostic yield on samples obtained range from 73% to 97%.

Glomerulonephritis

The clinical manifestations of glomerular renal disease are apt to consist only of varying degrees of hematuria, excretion of characteristic formed elements in the urine, proteinuria, and renal insufficiency and its complications. Excluding diabetes, purported immunologic renal diseases are the most common cause of proteinuria and the nephrotic syndrome.

Alterations in glomerular architecture as observed in tissue examined by light microscopy alone can be minimal, nonspecific, and difficult to interpret. For these reasons, specific diagnoses of renal disease require targeted immune fluorescent techniques for demonstrating a variety of antigens, antibodies, and complement fractions. Electron microscopy has complemented these immunologic methods. Tissue analysis can be assisted by blood tests of immunoglobulins (Ig), complement, and other mediators of inflammation.

There are two important humoral mechanisms leading to deposition of antibodies within the glomerulus. These are based on the location of the antigen, whether fixed within the kidney or present in soluble form in circulation. The fixed antigens are either a natural structural element of the glomerulus or foreign materials that have been trapped within the glomerulus for a variety of immunologic or physiochemical reasons. The best examples of the fixed natural antigens are those associated with the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). These antigens are evenly distributed in the GBM and cause characteristic linear IgG deposition, as determined in immunofluorescence studies. This process represents 5% of cases of immune-mediated glomerular disease and is referred to as anti-GBM disease. When this is coupled with pulmonary symptoms (antibodies directed against the alveolar membrane), it is known as Goodpasture’s syndrome. However, most patients with glomerular immune deposits have discontinuous immune aggregates caused by antibody binding to native renal cell antigens or to antigens trapped within the glomerulus. In addition, immune complexes formed in the circulation can deposit and accumulate in the GBM and the mesangium.

A group of immune-mediated nephritides characterized by necrotizing and crescentic architecture and rapid progression are referred to as pauci-immune glomerular nephritides because, while antibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease, they are rarely demonstrated within the glomeruli. These are known as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) diseases. Circulating antibodies against myeloperoxidase (MPO, P-ANCA) and proteinase 3 (PR3, C-ANCA) have been noted in microscopic angiitis and Wegener’s granulomatosis, respectively.

Cellular immune processes are likely to be stimulated and contribute in different ways in various other forms of glomerulonephritides.

The current classification of glomerulonephritis is based on the mechanism, the presence, and the localization of immune aggregates in the glomeruli.

Glomerulonephritis associated with postinfectious glomerulonephritis such as poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis.

Membranous nephropathy idiopathic or secondary to other causes such as systemic lupus erythematosus, cancer, gold, penicillamine.

Glomerulonephritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, type I idiopathic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C infection, bacterial endocarditis, and shunt nephritis.

IgA nephropathy, Schönlein–Henoch purpura.

Diffuse linear deposition of Ig.

Minimal change nephropathy.

Focal, segmental glomerulosclerosis.

Hemolytic–uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

ANCA-associated disease: Wegener’s granulomatosis and small-vessel vasculitis.

Type II MPGN (dense deposit disease).

- History of streptococcal infection.

- Mild generalized edema, mild hypertension, retinal hemorrhages.

- Gross hematuria; protein, erythrocyte casts, granular and hyaline casts, white blood cells (leukocytes), and renal epithelial cells in urine.

- Elevated antistreptolysin O titer, hypocomplementemia.

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is a disease affecting both kidneys. In most cases, recovery from the acute stage is complete, but progressive involvement may destroy renal tissue, leading to renal insufficiency. Acute glomerulonephritis is most common in children aged 3–10 years. By far the most common cause is an antecedent infection of the pharynx and tonsils or of the skin with group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, certain strains of which are nephritogenic. Nephritis occurs in 10–15% of children and young adults who have clinically evident infection with a nephritogenic strain. In children younger than 6 years, pyoderma (impetigo) is the most common antecedent; in older children and young adults, pharyngitis is a common antecedent. Occasionally, nephritis may follow infection due to other agents, hence the more general term postinfectious glomerulonephritis.

The pathogenesis of the glomerular lesion has been further elucidated by the use of new immunologic techniques (immunofluorescence) and electron microscopy. A likely sequel to infection is injury to the mesangial cells in the intercapillary space. The glomerulus may then become more easily damaged by antigen-antibody complexes developing from the immune response to the infection. Complement is deposited in association with IgG or alone in a granular pattern on the epithelial side of the basement membrane.

Gross examination of the involved kidney shows only punctate hemorrhages throughout the cortex. Microscopically, the primary alteration is in the glomeruli, which show proliferation and swelling of the mesangial and endothelial cells of the capillary tuft. The proliferation of capsular epithelium occurs, and around the tuft, there are collections of leukocytes, erythrocytes, and exudate. Edema of the interstitial tissue and cloudy swelling of the tubular epithelium are common. When severe, typical histologic findings in glomerulitis are enlarging crescents that become hyalinized and converted into scar tissue and obstruct the circulation through the glomerulus. Degenerative changes occur in the tubules, with fatty degeneration, necrosis, and ultimately scarring of the nephron.

Often the disease is mild, and there may be no reason to suspect renal involvement unless the urine is examined. In severe cases, about 2 weeks after the acute streptococcal infection, the patient has headache, malaise, mild fever, puffiness around the eyes and face, flank pain, and oliguria. Hematuria is usually noted as “bloody” or, if the urine is acid, as “brown” or “coca-cola colored.” There may be moderate tachycardia, dyspnea, and moderate to marked elevation of blood pressure. Tenderness in the costovertebral angle is common.

The diagnosis is confirmed by examination of the urine, which may be grossly bloody or coffee colored (acid hematin) or may show only microscopic hematuria. In addition, the urine contains protein (1−3+) and casts. Hyaline and granular casts are commonly found in large numbers, but the classic sign of glomerulitis, occasionally noted, is the erythrocyte cast. The erythrocyte cast is usually of small caliber, is intensely orange or red, and may show the mosaic pattern of the packed erythrocytes held together by the clot of fibrin and plasma protein.

With the impairment of renal function (decrease in glomerular filtration rate and blood flow) and with oliguria, plasma or serum urea nitrogen and creatinine become elevated, the levels varying with the severity of the renal lesion. A mild normochromic anemia may result from fluid retention and dilution.

Infection of the throat with nephritogenic streptococci is frequently followed by increasing antistreptolysin O titers in the serum, whereas high titers are usually not demonstrable following skin infections. The streptozyme test is available consisting of five antistreptococcal antibodies, and has a diagnostic yield of 95% among those with pharyngitis and 80% of those with a skin infection as precipitating events.

Serum complement levels are usually low.

Confirmation of diagnosis is made by examination of the urine, although the history and clinical findings in typical cases leave little doubt. The finding of erythrocytes in a cast is proof that erythrocytes were present in the renal tubules and did not arise from elsewhere in the genitourinary tract.

Due to the lag in symptoms weeks after the antecedent infection, only 25% of patients will have positive throat or skin cultures.

This is often not necessary; however, if the pattern of presentation deviates significantly from expected, a tissue diagnosis may help differentiate between differential diagnoses. For example, recurrent hematuria may indicate IgA nephropathy, whereas a persistently depressed complement (C3) level 6 weeks and beyond suggests a diagnosis of membrano-proliferative glomerulonephritis.

There is no specific treatment. Eradication of infection, prevention of overhydration and hypertension, and prompt treatment of complications such as hypertensive encephalopathy and heart failure require careful management. Some have used intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone in patients with significant crescents at biopsy, but this is not a universal practice.

Most patients with the acute disease recover completely; 5–20% show progressive renal damage. This damage may be evident only years after the immune injury. If oliguria, heart failure, or hypertensive encephalopathy is severe, death may occur during the acute attack. Even with severe acute disease, however, recovery is the rule, particularly in children.

Primary hematuria (idiopathic benign and recurrent hematuria, Berger’s disease) is now known to be an immune complex glomerulopathy in which deposition of IgA occurs in a granular pattern in the mesangium of the glomerulus. The associated light microscopic findings are variable and range from normal to extensive crescentic glomerulonephritis.

Recurrent macroscopic and microscopic hematuria and mild proteinuria are usually the only manifestations of renal disease. Most patients with IgA nephropathy are between the ages of 16 and 35 years at the time of diagnosis. The disease occurs much more frequently in males than in females and is the most common cause of glomerulonephritis among Asians and in the developed world. While most patients continue to have episodes of gross hematuria or microscopic hematuria, renal function is likely to remain stable. However, approximately 30% of patients will have progressive renal dysfunction and develop end-stage renal disease. Clinical features that indicate a poor prognosis include male sex, older age at onset of disease, the presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypertension, or renal dysfunction at presentation.

There is no satisfactory therapy for IgA nephropathy. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockade in an effort to lower proteinuria and delay progression of chronic kidney disease should be first-line therapy. The role of immunosuppressive drugs such as steroids and cytotoxic agents is not clear, and there have been few rigorously performed controlled trials. A more intriguing approach is the use of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oils) to delay progression of the renal disease. A large, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with IgA nephropathy using 12 g of omega-3 fatty acids has shown that fish oils probably can reduce the deterioration of renal function and the number of patients in whom end-stage renal disease develops.

After renal transplantation, recurrent IgA disease has been described. The risk varies from 21% to 58%. Of those who develop graft dysfunction attributable to recurrence, eventual graft loss occurred in 46–71% of patients. It is disputable whether allografts from living related donors confer a greater risk of recurrence than deceased or living unrelated donors.