Cutaneous Conditions

Julia Zakhaleva

Marvin L. Corman

What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues That, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion, Make yourselves scabs?

—William Shakespeare: Coriolanus I, i, 168

Dermatologic anal problems are often trivialized by the surgeon, who may categorize them as complaints attributable to a psychoneurotic or anal-obsessive personality. The patient may be referred directly to a dermatologist or may be given any one of a number of proprietary creams or the ubiquitous topical steroid, without the benefit of a physical examination. Dermatologists are understandably more adept at establishing the diagnosis of skin problems and usually perform a biopsy for confirmation in questionable cases, but the dermatologist is loath to perform a rectal examination and rarely has endoscopic equipment available. In our opinion, therefore, patients with anal complaints, including perianal dermatologic problems, should be seen by a physician or surgeon who has the knowledge and the instruments necessary to perform a complete rectal evaluation. If the condition appears to be limited to the skin and of uncertain diagnosis, consultation with a dermatologist is certainly appropriate.

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the skin conditions that affect the perianal area, emphasizing the differential diagnosis, indications for biopsy, and treatment of the relevant diseases. Those conditions that may be found in the anal area that are only incidental to a systemic cutaneous process are mentioned en passant if recognition of the disease in the area is believed to be unique or of particular interest. However, this chapter is not meant to be a précis of a textbook of dermatology.

▶ CLASSIFICATION

Dermatologic diseases may be categorized in a number of ways: based on the type of lesion (e.g., flat, elevated, depressed), according to whether they are primary or secondary, histopathologically, or by the commonly employed classifications of inflammation, infection, and neoplasm. A modification using this last method is illustrated as follows:

Dermatologic Anal Conditions

Inflammatory Diseases

Pruritus ani

Psoriasis

Lichen planus

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

Atrophoderma

Contact (i.e., allergic) dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis

Radiodermatitis

Behçet’s syndrome

Lupus erythematosus

Dermatomyositis

Scleroderma

Erythema multiforme

Familial benign chronic pemphigus (i.e., Hailey-Hailey)

Pemphigus vulgaris

Cicatricial pemphigoidpa

Infectious Diseases

Nonvenereal

Pilonidal sinus

Suppurative hidradenitis

Anorectal abscess and anal fistula

Crohn’s disease

Tuberculosis

Actinomycosis

Fournier’s gangrene

Ecthyma gangrenosum

Herpes zoster

Vaccinia

Tinea cruris

Majocchi’s granuloma

Candidiasis (i.e., moniliasis)

“Deep” mycoses

Amebiasis cutis

Trichomoniasis

Schistosomiasis cutis

Bilharziasis

Oxyuriasis (e.g., pinworm, enterobiasis)

Creeping eruption (i.e., larva migrans)

Larva currens

Cimicosis (i.e., bedbug bites)

Pediculosis

Scabies

Venereal

Gonorrhea

Syphilis Chancroid

Granuloma inguinale

Lymphogranuloma venereum (Chlamydia infection)

Molluscum contagiosum

Herpes genitalis

Condylomata acuminata

Premalignant and Malignant Diseases

Acanthosis nigricans Leukoplakia Mycosis fungoides Leukemia cutis Basal cell carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma Malignant melanoma Bowen’s disease Extramammary Paget’s disease

▶ INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Pruritus Ani

Itching in the perianal area, pruritus ani, is a frequently voiced complaint. In fact, it is a symptom that was well recognized in antiquity. In the earliest manuscript exclusively devoted to anorectal disorders, the Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus, 10 of its 41 remedies were devoted to the management of anal itching and irritation.29 By far the most common anorectal symptom presenting to the dermatologist is pruritus ani.11 The rich nerve supply to the perianal area is thought to be the primary reason for the sensitivity to potential irritants.270

Symptoms

Itching is usually noted in the anal or occasionally the genital areas, but the condition is not generalized. Although the anus is frequently the site for autoeroticism, most individuals do not appear to fall into this category. The condition tends to be worse at night, awakening the patient from sleep. This leads to scratching, which exacerbates the complaint even further. Pruritus ani is more common in men.

Differential Diagnosis

Although the symptoms may be associated with a specific condition (e.g., hemorrhoids,286 anal fissure, scarring from prior anal surgery, or with constipation or diarrhea), most patients are not found to have significant anorectal pathology except for the obvious skin changes. Besides anorectal disease, allergic dermatitis (i.e., contact), mycoses, seborrhea, diabetes, and oxyuriasis (pinworm) have all been implicated as causative factors. Other dermatologic problems, such as psoriasis (see later), should be considered. In addition, the possibility of harboring a systemic disease, such as diabetes, may necessitate further studies. Anal neurodermatitis may cause violent itching, which may lead to tearing of the perianal area (Figure 9-1). With chronicity, the skin can become atrophic or hypertrophic, with nodularity and scarring (Figure 9-2).

Special Studies

Physiologic studies have demonstrated that in patients with idiopathic pruritus ani, the anal sphincter relaxes in response to rectal distension more readily than in those with no anal disease.148 Allan and colleagues showed that individuals harboring pruritic symptoms without coexisting anal pathologic features had a significantly greater fall of anal pressure when a rectal balloon was inflated (57%) than did a control population (40%).13 Others have observed that patients with idiopathic pruritus ani have an abnormal rectoanal inhibitory reflex and a lower threshold for internal sphincter relaxation during such studies as the saline continence test.150 It is therefore postulated that pruritus and soiling in some patients may occur as a result of a defect in anal sphincter function.

Evaluation

Physical examination should include anoscopy and proctosigmoidoscopy to look for a local cause of the symptoms. Daniel and colleagues reviewed 109 individuals with pruritus ani as the only presenting symptom and concluded that those with complaints of long duration should undergo evaluation

for proximal colon and anorectal neoplasms.109 Usually, however, the procedures are unrewarding. Examination with a magnifying lens may be helpful.107 Evaluation with Wood’s lamp may reveal fluorescence,356 but this equipment is usually not readily available in the office practice of most physicians and surgeons. If suspicion warrants, skin scrapings of the perianal area may be examined using a potassium hydroxide slide preparation and should be cultured on Sabouraud’s medium for yeast and fungi (see Fungal Infections). However, because there is no good evidence to suggest that abnormal fecal flora contributes to the symptoms, neither qualitative nor quantitative assessment of the stool is considered appropriate.351

for proximal colon and anorectal neoplasms.109 Usually, however, the procedures are unrewarding. Examination with a magnifying lens may be helpful.107 Evaluation with Wood’s lamp may reveal fluorescence,356 but this equipment is usually not readily available in the office practice of most physicians and surgeons. If suspicion warrants, skin scrapings of the perianal area may be examined using a potassium hydroxide slide preparation and should be cultured on Sabouraud’s medium for yeast and fungi (see Fungal Infections). However, because there is no good evidence to suggest that abnormal fecal flora contributes to the symptoms, neither qualitative nor quantitative assessment of the stool is considered appropriate.351

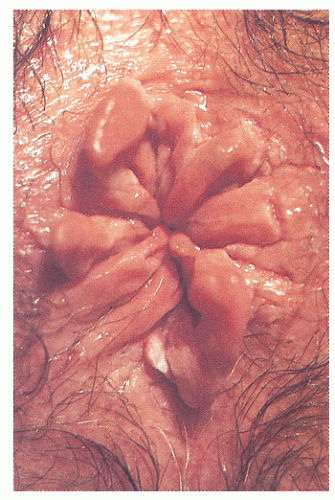

FIGURE 9-2. Marked edema with papillomatosis and nodularity resulting from chronic abrading is characteristic of pruritus ani. (Courtesy of William G. Robertson, MD.) |

Treatment

Pruritus ani has traditionally been considered a condition that eludes all attempts at cure. Numerous potions, nostrums, and lotions have been employed with varying degrees of success, as well as more aggressive treatment, such as injection of local anesthetics, phenol, and alcohol.366,367 Excision and skin grafting have also been suggested. Eusebio and colleagues reported “long-term cure” with the use of up to 30 mL of 0.5% methylene blue (i.e., methylthionine chloride) injected intradermally and subcutaneously in 23 individuals with intractable pruritus ani.147

Psychological factors have been thought to play a role in contributing to symptoms. However, there has never been objective evidence to demonstrate a statistically significant deviation from a normal personality.14 It is reasonable to assume that severe perianal itching, 24 hours a day, every day, is likely to make an individual rather irascible.

In recent years, attention has been drawn to the role of diet in the cause of the condition; therefore, an accurately obtained history will often dictate the appropriate treatment. Items that have been implicated include the following:

Coffee (caffeine)

Tea (caffeine)

Carbonated beverages, especially caffeinated colas

Milk products

Alcohol, particularly wine and beer

Tomatoes and tomato products, such as ketchup

Cheese

Chocolate

Citrus fruits, grapes, prunes, figs349

Cigarette smoking is another factor. It is postulated that all these products induce mucous discharge, probably through a systemic route, or possibly in some instances by changing the pH of the stool.

Because most individuals indulge in one or more of the foregoing substances, it is probable that the physician will receive at least one affirmative response when inquiring about the dietary history. By recognizing the association of one of these agents with pruritus ani, a patient will become an ally of the surgeon. It is therefore important to solicit an individual’s understanding and cooperation.29 A patient may have been previously told that the problem is psychoneurotic, so that the physician’s reassurance and sympathy are beneficial factors that contribute to a satisfactory resolution. Removing or changing the dietary factor may cause the symptoms to disappear. Gradual reintroduction of the potentially causative dietary substance is then used to calculate the acceptable daily level.349 Additionally, promoting complete evacuation with increased fluids and bulking agents (e.g., bran, psyllium) may help avoid the irritation.42 Rectal irrigation and a bowel management program also may be necessary for those individuals who experience incontinence or leakage of stool (see Chapter 16).

Despite the validity of the previous suggestions, the most important advice that can be given is usually directed toward the management of anal hygiene. Many individuals perceive their problem to be one of lack of cleanliness; the opposite is more likely. Vigorous scrubbing of the area with soap and water will cause the skin to be defatted, and contact dermatitis may supervene. Rarely have I identified a patient with pruritus who was not scrupulous with respect to anal cleanliness (one rather stoic individual even used steel wool); the difficulty is to convince the person that the anal area need not be sterilized.

One should advise the patient to remove the soap from the area! The perineum should be cleansed with plain water, particularly when bathing or showering, and ideally even following defecation. Irrigating the rectum with warm water through a bulb syringe is often ameliorating. Some individuals may actually be allergic to toilet paper, so that in stubborn cases a moist cloth should be used for cleansing. Even in a public toilet, a moistened paper towel is preferable to the irritative effects of continued rubbing with toilet paper. For those with copious discharge, a cotton ball placed at the anal verge, changed as necessary, may be helpful.

Heat and sweat tend to exacerbate pruritus. Although there is no evidence concerning the causative effect of clothes, patients should wear garments and underwear that allow air circulation and dryness. Residue remaining on

the clothes after the use of detergents based on biologic enzymes may result in itching, and these should be avoided.349

the clothes after the use of detergents based on biologic enzymes may result in itching, and these should be avoided.349

A wealth of topical creams and ointments, obtained over the counter and by prescription, is available for the pruritus ani sufferer. The use of anesthetic ointments and creams (e.g., dibucaine [Nupercainal], pramoxine [Tronolane], benzocaine [Americaine], lidocaine [ELA-Max 5]) is not advised except on a highly limited basis. Symptoms are only temporarily masked, the underlying problem is not addressed, and allergic dermatitis can develop. Soothing creams and lotions are generally preferred to ointments; many are quite satisfactory (e.g., mineral oil and lanolin [Balneol], witch hazel and glycerin [Tucks], pramoxine [Prax]). For more severe skin cracking, bath treatment with Aveeno colloidal oatmeal may be quite helpful.

The brief, severe, burning sensation produced by topical capsaicin results in an inhibitory feedback, which may eliminate the need to scratch. A randomized crossover study showed topical 0.006% capsaicin cream applied three times a day to be effective in those who had pruritus ani for greater than 3 months.261

When the proprietary preparation fails, one must consider using a topical steroid; this almost inevitably will bring immediate relief. My own preference is to use Proctocort (1% hydrocortisone cream) or 2.5% Analpram-HC (hydrocortisone and pramoxine) because they are nicely packaged with a plastic applicator. The medication is applied at bedtime and once or twice more during the day, if necessary. It should be discontinued, however, as soon as symptoms resolve, in order to avoid skin atrophy (see Atrophoderma). Prolonged use of topical steroids can also result in the rebound itch after cessation requiring further use; this has often been described as an addiction.230 Dasan and colleagues opine that patients with unresolved, long-standing pruritus ani and with no other symptoms to suggest colorectal disease should be referred to a dermatologist for assessment and patch testing (see Allergic Dermatitis).111

Systemic antihistamines may reduce nocturnal scratching,43 thus aiding sleep rather than addressing local inhibition. However, there have been no randomized trials evaluating the usefulness of antihistamines in the management of pruritus ani.

Anal tattooing, or intradermal injection of methylene blue, may be considered in those who have failed other treatment measures, have become steroid dependent, or in whom symptoms severely impact quality of life. The postulated mechanism of action is destruction of nerve endings. However, the adverse effects include skin ulceration and necrosis.269 In the intractable case, sedatives and tranquilizers may be considered. In addition, biofeedback and selfhypnosis have been of demonstrable benefit with some patients. Consultation with a professional familiar with these techniques may be advisable.

Psoriasis

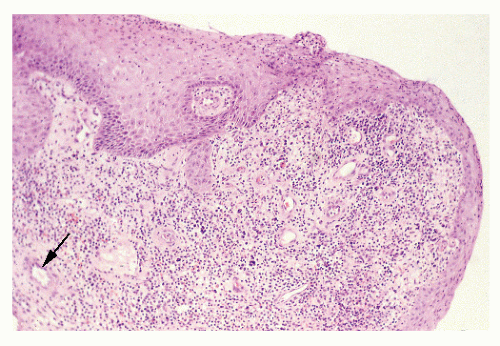

Psoriasis is a common, immune-mediated, chronic inflammatory disease of the skin, characterized by rounded, circumscribed, erythematous, dry, scaling patches covered by grayish white or silvery white scales.291 The lesions have a predilection for the scalp, nails, extensor surfaces of the limbs, elbows, knees, and the sacral region.112 When the condition occurs in the anal area, it may cause severe pruritic symptoms. Perianal psoriasis is usually sharply marginated, with a characteristic butterfly distribution extending over the coccyx and sacrum (Figure 9-3). Psoriatic lesions are often present at other sites on the body. Smoking is associated with an increased risk of psoriasis and also with increased severity.160,190,288 Psoriasis is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease,

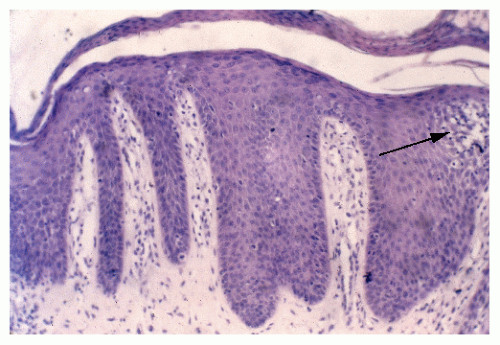

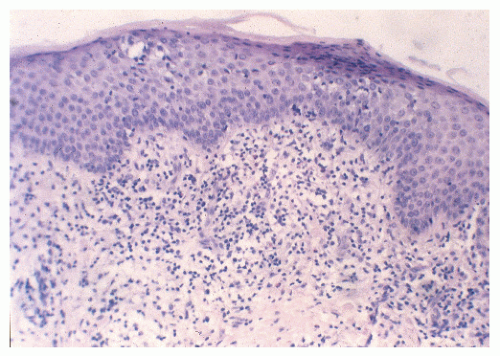

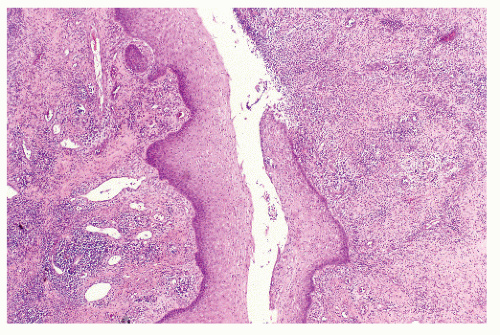

and atherosclerotic disease in noncardiac sites.169,316 A recent large observational study suggests the association of psoriasis with malignancy unrelated to the treatment with immunosuppressants.56 Histologically, characteristic features include epidermal thickening (i.e., acanthosis), regular elongation of the rete ridges with broadening of the deeper aspect, and elongation with edema of the dermal papillae (Figure 9-4). There may be increased mitotic activity in the epidermis. Cells of the stratum corneum usually have retained nuclei (i.e., parakeratosis). Focal collections of neutrophils in the subcorneum are known as Munro’s microabscesses.

and atherosclerotic disease in noncardiac sites.169,316 A recent large observational study suggests the association of psoriasis with malignancy unrelated to the treatment with immunosuppressants.56 Histologically, characteristic features include epidermal thickening (i.e., acanthosis), regular elongation of the rete ridges with broadening of the deeper aspect, and elongation with edema of the dermal papillae (Figure 9-4). There may be increased mitotic activity in the epidermis. Cells of the stratum corneum usually have retained nuclei (i.e., parakeratosis). Focal collections of neutrophils in the subcorneum are known as Munro’s microabscesses.

Treatment may simply consist of moisturizers (emollients) and agents containing salicylic acid. Topical agents include corticosteroids, coal tar products, anthralin, retinoid (tazarotene), a vitamin D3 derivative (calcipotriene), or a combination of these. In addition, the application of sunlight (not terribly practical for perianal disease) and the use of ultraviolet light B (UVB) have been found to be beneficial. More recently, the so-called PUVA treatment has been advocated. This consists of a combined systemic-external therapy, using a potent photoactive agent (i.e., psoralen) followed by administration of a special light system emitting long-wave UVA. Cancer chemotherapeutic drugs, such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, have also been advocated.

One may understandably be reluctant to treat psoriasis without dermatologic consultation unless the condition is localized to the perianal area and then only for a limited course.

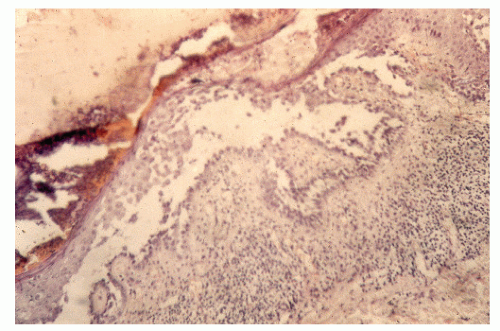

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a skin condition that consists of an eruption of small, flat-topped papules with a distinct violaceous color and polypoid configuration. The cutaneous manifestations begin on the volar aspects of the wrists and forearms. The lesion is characteristically found on the flexor surfaces, mucous membranes, genitalia (25%), and occasionally in the perianal area. Wickham striae are intersecting gray lines that can be seen if mineral oil is applied to the plaques. This helps to establish the diagnosis.269 There have been rare reports of squamous cell carcinoma developing within lichen planus in the anal area.164 This condition may be seen in patients with disease processes characterized by altered cell-mediated immune responses.269

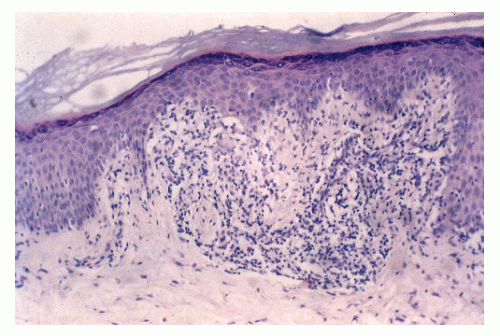

Histologically, the papule shows focal thickening of the granular layer, degeneration of the basement membrane and basal cells, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis (Figure 9-5). Biopsy of the skin establishes the diagnosis.

Treatment often has less than satisfactory results, with corticosteroids appearing to be the most helpful for this condition. Topical preparations with occlusive dressings are quite useful, and systemic administration and intralesional injections have also been employed. In mild cases, antipruritic lotions and antihistamines are suggested. Rest is also helpful.

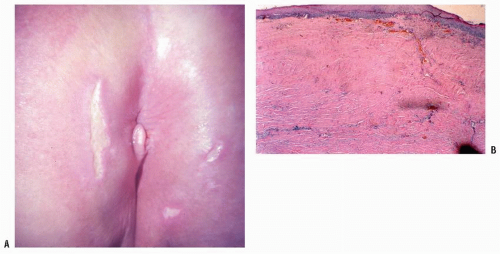

Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an unusual condition of unknown cause. It occurs much more frequently in women than in men. The genital area appears to be the most commonly involved site.

Physical examination may reveal the characteristic “inverted keyhole” distribution. In this situation, the disease extends beyond the mucocutaneous border to involve the skin of the vulva, perineum, and perianal area. In the vulva, the condition affects the labia, vestibule, and introitus (Figure 9-6). Discomfort, pruritus, dysuria, and dyspareunia are common complaints.

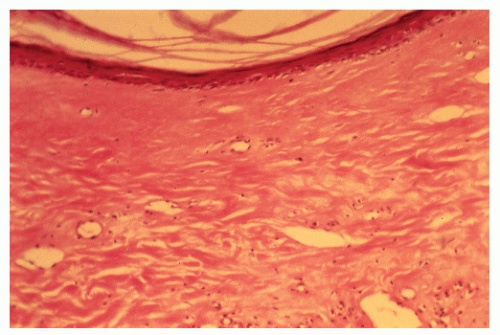

The characteristic histologic changes in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus are edema and homogenization of the collagen below the epidermis (Figure 9-7). The epidermis also shows variable hyperkeratosis and follicular plugging. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. An association between the condition and squamous cell carcinoma of the perianal region has also been noted.354

Because of the small risk of malignancy, all nonresponders or those with recurrent sclerosis should have a skin biopsy.349

Treatment is primarily directed to the relief of the pruritic complaints in the hope of lessening the risk for leukoplakia

and carcinoma. A mild topical steroid sufficient to control the symptoms is advocated. Retinoids and testosterone creams have also been described.275,345 Secondary infection should be treated with appropriate antibiotics.

and carcinoma. A mild topical steroid sufficient to control the symptoms is advocated. Retinoids and testosterone creams have also been described.275,345 Secondary infection should be treated with appropriate antibiotics.

Atrophoderma or Atrophy of the Skin

Atrophy of the skin is a reaction to the repeated and prolonged application of topical corticosteroids; it may also follow local injection of these products.173 Telangiectasia occurs, indicating loss of dermal collagen, and the patient who initially complained of pruritus subsequently reports discomfort and burning.357 The friction of walking rubs the already atrophic and thinned epidermis.

Patients usually report a history of self-application of topical corticosteroids for many years. Attempting to remove the medication is frequently unsuccessful. Biopsy may reveal atrophy and hyperkeratosis. Because of the risk for development of this condition, it is important to discontinue the use of cortisone treatment as soon as possible.

Irritant and Contact or Allergic Dermatitis

Two types of dermatitis are caused by substances coming into contact with the skin:

Irritant dermatitis (caused by a nonallergic reaction following exposure to an irritating substance)

Allergic (contact) dermatitis caused by allergic sensitiza tion to a number of agents122

Irritants include alkalis, acids, metal salts, dusts, gases, and hydrocarbons. Allergic contact dermatitis results from hypersensitivity of the delayed type, also known as cellmediated hypersensitivity or immunity.122 A person may be exposed to an allergen for many years before hypersensitivity develops. The allergens are numerous and varied, as follows:

Dyes

Oils

Resins

Chemicals used for fabrics, cosmetics, and insecticides

Products or the substances of bacteria, fungi, and parasites122

The most common causes of contact dermatitis are as follows, in order of frequency:

Poison ivy, oak, and sumac

Paraphenylenediamine

Nickel

Common rubber compounds

Neomycin

Dichromates154

The patch test is used to detect hypersensitivity to a substance that is in contact with the skin (see Pruritus Ani). A nonirritating concentration of agents suspected to be the cause of the contact dermatitis is applied. The patches

remain in place for 48 hours, less if burning or itching occurs. A positive reaction will produce severe pruritus and erythema or vesicles. It is wise to defer this test, however, until the rash has cleared to limit the likelihood of a severe exacerbation.

remain in place for 48 hours, less if burning or itching occurs. A positive reaction will produce severe pruritus and erythema or vesicles. It is wise to defer this test, however, until the rash has cleared to limit the likelihood of a severe exacerbation.

Therapy obviously is directed toward removing the underlying cause of the skin problem or the allergen. Iodine and adhesive tape are common dermatitis-inducing products in patients who undergo anal surgery. Soothing compresses such as Aveeno colloidal oatmeal, in addition to corticosteroids and possibly antipruritics, may be advisable.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic, superficial, inflammatory disease of the skin, with a predilection for the scalp, eyebrows, nasolabial crease, ears, axillae, submammary folds, umbilicus, groin, and natal cleft. The disease is characterized by dry, moist, or greasy scales and by crusted, pink-yellow patches of diverse size and shape.124 The condition is believed to be caused by hypersecretion of sebum and is apparently exacerbated by increased perspiration and emotional stress. A high fat intake is frequently noted.

Histologically, the picture is not dissimilar to that of psoriasis, but Munro’s abscesses are not seen. According to one school of thought, the two conditions are so similar that there is some justification for thinking their origin may be the same. However, more recent evidence favors a role for yeast organisms in the etiology of the condition, with therapy being directed accordingly. Still, application of corticosteroids is the primary therapy.

Atopic Dermatitis or Atopic Eczema

The term atopy is derived from the Greek word meaning “out of place“ or “strange.” It is defined as the tendency for allergies to manifest themselves by systemic symptoms, such as asthma, hay fever, and eczema.121 The condition is believed to be either a form of immunologic deficiency or possibly a blockade of β-adrenergic receptors in the skin.

Atopic dermatitis can occur as localized, erythematous, scaly, papular, or vesicular patches or in the form of pruritic, lichenified lesions.124 The condition is often paroxysmal, with an emotional upset initiating some attacks. Other factors exacerbating the problem may be clothing, certain foods, and dryness of the skin. Superimposed infections such as intertrigo and dermatophytosis may produce further recurrences. The most common secondary skin infections in atopic dermatitis are caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Staphylococcus aureus.303 In the absence of clinical signs of infection, most atopic dermatitis patients are also colonized with S. aureus on their skin lesions. This pathogen produces proinflammatory factors that trigger the cutaneous immune system.340 The severity of dermatitis correlates with the density of S. aureus colonization of skin lesions.406 Anti-S. aureus antibiotics have been shown to improve the severity of atopic dermatitis.59 Histologically, hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with acanthosis are noted (Figure 9-8). When lichenification is present, the acanthosis is increased, and there is papillomatosis, with long papillary bodies reaching to the stratum corneum. These changes may somewhat resemble those seen in psoriasis.

Treatment consists of avoiding emotional stress, if possible; avoiding extremes of cold and heat; limiting the use of stimulant beverages; and using oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Prednisone, 30 to 40 mg orally for 4 to 6 weeks or possibly longer, is usually recommended. Alternatively, a parenteral preparation may be substituted.

Radiodermatitis

Radiodermatitis is a particular problem in the anal area because current therapy for carcinoma of the rectum, anus, and prostate often involves ionizing radiation. In some individuals, unfortunately, the side effects of the cancer treatment may actually lead to worse symptoms than the original disease (see Chapters 24 and 25).

Many changes are found in the cell as the result of radiation therapy. Mitoses are temporarily arrested, chromosomal abnormalities occur, and there is at least a temporary halt in the normal cell cycle. The amount of skin change resulting from radiotherapy depends on the dose. These alterations may be manifested as erythema, edema, and ulceration, and symptoms may include burning, itching, or severe pain. After a period, telangiectasia, atrophy, and freckling may appear. The skin becomes dry, thin, smooth, and shiny (Figure 9-9). Radiation injury may result in the subsequent development of malignancy, in most cases following a rather prolonged latent period. The manifestations of this complication increase with the passage of time.

Results of treatment are often less than satisfactory. However, symptomatic improvement has been reported with a regimen consisting of oral vitamin A, 8,000 IU, given twice daily.251 Hyperbaric oxygen treatment has also been recommended. Cleansing the area with mild soap and water, in addition to the use of an emollient, a corticosteroid preparation, or both, may be of help. Biopsy specimens should be taken from any suspected lesions.

Behçet’s Syndrome

Behçet’s syndrome is characterized by four main symptoms: recurrent aphthous ulcers in the mouth, skin lesions, eye lesions, and genital ulcerations.197 Genital ulcerations may be found in persons of both sexes on the genitocrural fold, on the anus, on the perineum, or in the rectum. Scrotal scarring secondary to ulcers is rarely found in conditions other

than Behçet’s syndrome. Although the cause of the condition is unknown, there is some evidence to suggest that it is of viral origin or possibly represents an autoimmune disease. Behçet’s is one of the few forms of vasculitis in which there is a known genetic predisposition. Histologically, the lesions usually show vasculitis involving vessels of all sizes—small, medium, and large—on both the arterial and venous sides of the circulation.

than Behçet’s syndrome. Although the cause of the condition is unknown, there is some evidence to suggest that it is of viral origin or possibly represents an autoimmune disease. Behçet’s is one of the few forms of vasculitis in which there is a known genetic predisposition. Histologically, the lesions usually show vasculitis involving vessels of all sizes—small, medium, and large—on both the arterial and venous sides of the circulation.

The anal condition may be misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids, fissure, Crohn’s disease, condylomata, or STI.197 Surgery is contraindicated, and corticosteroid treatment, systemically or topically, is the preferred treatment (see also Chapter 28).

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus, like other connective tissue diseases, only rarely occurs in the anal area and still more rarely develops as an isolated finding in this location. The cutaneous manifestation is called discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). It may begin with single or multiple lesions involving entire regions of the body, especially the head and neck, sternum, vulva, and perineum. The typical plaque is approximately 1 cm or more in diameter, with characteristic scales. Removal of the scales reveals patulous follicular orifices with dry, horny, keratinous plugs.123 Occasionally, basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma may develop in long-standing DLE lesions.

In laboratory investigation, the LE cell test usually yields a negative result in DLE. Results of the direct immunofluorescence test are usually positive, however, as are antinuclear antibody test results.

Treatment consists of avoidance of strong sunlight, extremes in temperature, and localized trauma. Smoking cessation is recommended because smokers tend to have more active disease.159,170 Corticosteroid creams and ointments are particularly beneficial, with intralesional steroid therapy often helpful. Systemic therapy with antimalarials and immunosuppressive agents also has been advised.

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis (polymyositis) is an inflammatory condition that produces angiopathy in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscles. Women are twice as likely to be affected as men. Many clinical and serologic features of the disease vary widely among affected individuals, depending on the patient’s immunogenetic profile and a host of potential environmental triggers.344,300 The disease usually starts on the face and eyelids as a heliotrope rash and may spread to other areas forming a “shawl sign” of diffuse, flat, erythematous lesions over the chest and shoulders and affecting the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints in a symmetric fashion (so-called Gottron’s sign). It is associated with a number of other disturbances, including Raynaud’s phenomenon, alopecia, urticaria, and erythema multiforme. Of particular interest to the surgeon is that in patients older than 40 years of age, visceral cancer is frequently associated with the condition. The spectrum of malignancies usually parallels the distribution in the general population with a few exceptions. Dermatomyositis carries an increased risk of cancer mortality compared with the general population.63,350,417 Additional risk factors for malignancy include evidence of capillary damage on muscle biopsy,390 cutaneous necrosis of the trunk,34 cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis,195 and older age (older than 65) at the diagnosis of dermatomyositis.267 Histologic changes are similar to those of lupus erythematosus. Treatment consists of rest, salicylates, steroids, methotrexate, and azathioprine.

Scleroderma or Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

Scleroderma is characterized by the appearance of areas that are immobile and give the skin the appearance of being “hidebound.”123 The skin becomes smooth, yellowish, and

firm, and it shrinks so that the underlying structures are bound down. Although the condition frequently involves the face and hands, leading to an expressionless appearance on the former and a clawlike appearance of the latter, it can progress to involve most of the internal organs. Involvement of the small intestine may cause constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal distension. Although the colon is only rarely affected, it can produce the signs and symptoms of Ogilvie’s syndrome (see Chapter 20). Systemic sclerosis appears to be associated with a modest increase in the overall risk of malignant disease.114 The most significant association appears to be with lung cancer.46,76 There is also an association with skin cancer, hepatoma, and hematopoietic malignancies,314 and there is a marked increase in the risk of esophageal carcinoma and oropharyngeal carcinoma.334 Treatment consists of supportive measures, baths, a high-protein diet, corticosteroids, and a number of other medications, including immunosuppressives.

firm, and it shrinks so that the underlying structures are bound down. Although the condition frequently involves the face and hands, leading to an expressionless appearance on the former and a clawlike appearance of the latter, it can progress to involve most of the internal organs. Involvement of the small intestine may cause constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal distension. Although the colon is only rarely affected, it can produce the signs and symptoms of Ogilvie’s syndrome (see Chapter 20). Systemic sclerosis appears to be associated with a modest increase in the overall risk of malignant disease.114 The most significant association appears to be with lung cancer.46,76 There is also an association with skin cancer, hepatoma, and hematopoietic malignancies,314 and there is a marked increase in the risk of esophageal carcinoma and oropharyngeal carcinoma.334 Treatment consists of supportive measures, baths, a high-protein diet, corticosteroids, and a number of other medications, including immunosuppressives.

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a clinically and histologically distinctive skin disease that is precipitated by the following conditions, among others:

Viral infections

Bacterial infections

Radiotherapy

Carcinomatosis

Pregnancy

Connective tissue diseases

Drug reactions

The mechanism for this particular reaction is unknown. The lesions present as flat, dull red maculopapules that may be rather small or may increase to 1 or 2 cm in 48 hours. The periphery may remain red, whereas the center is purpuric. The lesions look almost like targets. They commonly appear in the oral mucous membrane, but genital lesions are also frequent.

Histologically, the abnormality is confined to the upper dermis and lower epidermis. In more severe cases, there is necrosis of the whole epidermis. Bullae usually are subepidermal.

Treatment consists of symptomatic relief in mild cases, but in severe instances the use of corticosteroids has been suggested. Antibiotics are advised if secondary infection develops.

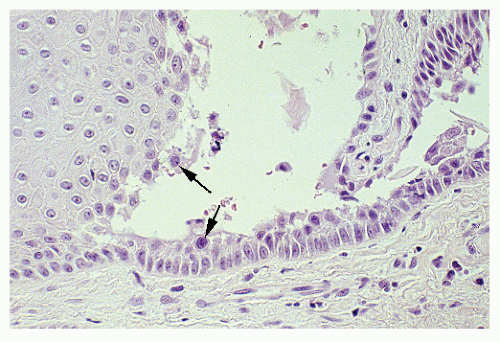

Familial Benign Chronic Pemphigus or Hailey-Hailey

Familial benign chronic pemphigus is a hereditary disease characterized by a recurrent bullous and vesicular dermatitis of the neck, axillae, flexors, and surfaces that appose. The condition has been found localized to the perianal area and may pose confusion in differential diagnosis (Figure 9-10).404 The disease is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. It generally presents between the second and the fourth decade. Usually, the disease persists throughout life and is triggered by UV light, friction, sweating, and bacterial infections.

The condition is caused by a defect in keratinocyte adhesion based on the mutation of the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-q24.67 The histologic pattern is unique, with prominent intraepidermal vesicles and bullae (Figure 9-11).

FIGURE 9-10. Hailey-Hailey. A macerated erythematous patch has welldefined borders. (Courtesy of Samuel L. Moschella, MD.) |

Treatment consists of local or systemic antibiotics and the use of topical corticosteroids. Additionally, low-dose radiation treatment has been recommended. Localized areas have been treated by excision and skin grafting.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by bullae appearing on apparently normal skin and mucous membranes.127 The lesions usually begin first in the mouth and next

in the groin, scalp, face, neck, axillae, and genitals (Figure 9-12). It appears that an autoimmune mechanism is the cause. The condition occurs equally in both sexes, usually in adults in their fifth and sixth decades. Circulating intercellular antibodies directed against desmoglein, an adhesion molecule, may be demonstrated in these individuals.18,364

in the groin, scalp, face, neck, axillae, and genitals (Figure 9-12). It appears that an autoimmune mechanism is the cause. The condition occurs equally in both sexes, usually in adults in their fifth and sixth decades. Circulating intercellular antibodies directed against desmoglein, an adhesion molecule, may be demonstrated in these individuals.18,364

FIGURE 9-12. Pemphigus vulgaris. Bullae affect the perineum and buttocks with characteristic lesions. |

The pathologic changes are acantholysis, cleft and blister formation in the intraepidermal areas just above the basal cell layer, and the formation of acantholytic cells (Figure 9-13).127 Characteristic of the separation of keratinocytes is the presence of Tzanck’s cell lining the bulla, as well as lying free in the cavity.

Because of the pain associated with advanced cases, prolonged daily baths with permanganate solution may be advised. Silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) cream, which is effective in the treatment of burns, is also useful in this condition. High-dose corticosteroids (160 mg of prednisone daily) remain the primary therapy. Immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and methotrexate, are part of the multimodality approach, which may include antibiotics, antimalarials, gold, and plasmapheresis. Treatment with rituximab with or without intravenous immunoglobulin appears to be an effective therapy in patients with refractory disease.7,189,196

Cicatricial Pemphigoid or Benign Mucosal Pemphigoid

Cicatricial pemphigoid is characterized by the presence of transient vesicles that heal by scarring of mucous membranes. The condition most commonly occurs in the mouth and conjunctivae. Other areas of involvement include the pharynx, esophagus, genitalia, and anus. In rare cases, the lesion has been confined to the genital and anal areas.393 Direct immunofluorescence of the lesion reveals the presence of antibodies at the basement membrane. Individuals with autoantibodies directed at epiligrin (laminin 5) appear to have a high risk for adenocarcinoma.139 The absence of acantholysis differentiates the condition from pemphigus vulgaris.

There is no effective medication for cicatricial pemphigoid. Obstructing areas in the larynx and esophagus may require tracheostomy or gastrostomy.

▶ INFECTIOUS CONDITIONS

For the purposes of discussion, we have taken the liberty of classifying the infectious processes as those that are nonvenereal and those that are usually attributable to venereal causes.

Nonvenereal Infections

Pilonidal Sinus

Pilonidal sinus is a common infective process occurring in the natal cleft and sacrococcygeal region. It primarily affects young adults and teenagers. There is a 3:1 male predominance. In the military in particular, it has been a considerable source of concern regarding personnel and economics. For example, more than 77,000 soldiers were admitted to army hospitals for symptoms from pilonidal sinus disease from 1942 through 1945, and they remained for an average of 44 days.332 In 1973, more than 70,000 patients were admitted to nongovernmental hospitals in the United States with the primary diagnosis of a pilonidal sinus.264 As recently as 1980, more than 40,000 patients with pilonidal disease were hospitalized in the United States, averaging more than 5 days of in-hospital care.31 Of course, this was before government and insurance company restrictions were applied in the United States concerning permissible days in the hospital for a given illness.

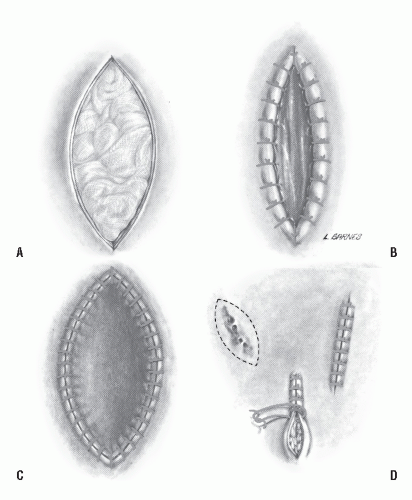

The condition was originally described by Anderson in a letter to the editor of the Boston Medical Surgical Journal of 1847 and was subsequently named “pilonidal sinus” by Hodges in 1880.19,192 The term literally means “nest of hair”; this is because the epithelium-lined sinus usually is found to contain hair.

When the sinus becomes infected, commonly after puberty, it drains from an opening or openings overlying the coccyx and sacrum (Figure 9-14). The infected abscess may extend to the perianal area in a presentation that may be

mistaken for an anal fistula. The disease can also be confused with suppurative hidradenitis (see later). Although the condition is by no means life threatening, it does cause considerable disability for many individuals. Time lost from school or work can amount to months.

mistaken for an anal fistula. The disease can also be confused with suppurative hidradenitis (see later). Although the condition is by no means life threatening, it does cause considerable disability for many individuals. Time lost from school or work can amount to months.

ABRAHAM WENDELL ANDERSON (1804-1876)

Anderson was born in Windham, Maine, the son of the first settlers in the town. He attended Gorham Academy and in 1829 graduated from Bowdoin Medical School. He established his practice in the town of Gray Corner, where he remained all his life. In 1868, he participated in the founding of the Cumberland County Medical Society and was elected its first president. In his letter, Anderson reports a 21-year-old man with what was thought to be a scrofulous sore on his back.19 The author found “a fistula opening near the os coccygis,” which he drained. Three weeks later, he drew out of the cavity “a hair, very finely matted, and about two inches in length.” The discharge stopped, and the wound healed rapidly.

RICHARD MANNING HODGES (1827-1896)

|

Hodges was born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. He graduated from Harvard College in the class of 1847 and subsequently received his MA and MD at Harvard Medical School. He then joined the faculty there in the department of anatomy as a demonstrator, a position he held until 1861. He was befriended by the renowned Boston surgeon, Henry Bigelow, who helped launch him toward a successful career in surgery. Hodges served on the Board of Overseers of Harvard College and as a visiting surgeon at the Massachusetts General Hospital. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Although many of his writings were on orthopedics and trauma, it is because of his article, read before the Boston Society for Medical Improvement, in which he names the condition “pilonidal sinus” that he is recognized today.

Etiology

The etiology of the condition has been the subject of some controversy and discussion. One possible theory that has been espoused is the failure of fusion in the embryo, with resultant entrapment of hair follicles in the sacrococcygeal region. Proponents of this theory are quick to point out the frequent incidence of eyebrow hair that meets in the midline in such patients. Another theory attributes the problem to the result of trauma, with the introduction of hair shafts into the subdermal area. Mechanical forces, such as suction, assist the hairs in penetrating deeper in the subcutaneous tissue. As a person sits or bends, this draws the skin of the natal cleft more taut, lifting it away from the underlying sacrococcygeal fascia. This creates negative pressure in the subcutaneous tissue, which draws hair deeper into the space. It has long been observed that the natal cleft is often deeper in patients with a pilonidal sinus, one of the variables that one may consider in determining the choice of surgical management, especially with those that flatten the cleft.8 Doll and colleagues observed that a family history of pilonidal sinus predisposes to an earlier onset of the condition and is associated with as much as a 50% long-term recurrence rate.119

Lord observed a number of interesting features of the condition.259 He believed that there was a constant relationship between the lateral sinus openings and the midline pits; the openings were always cephalad to the pits. Lord further observed the presence of 23 hairs of exactly the same length, diameter, color, and orientation in a patient. He postulated that it would be impossible for this number of hairs to follow each other into a pilonidal sinus and be identical in every respect. Lord applied this observation by proposing that the treatment of pilonidal sinus could therefore be made quite simple. He suggested that all that is required is the removal of the offending hair follicle and the hairs that have been shed. These observations were subsequently confirmed by Bascom, a concept that led to his proposed surgical approach (see later).31

Symptoms and Findings

The patient usually presents with pain, swelling, and purulent drainage at and around the site of the pilonidal opening. A solitary midline opening or pit may be observed, or there may be numerous openings, with pus draining and hair protruding. The typical appearance of an abscess that can be found anywhere in the skin and subcutaneous tissue may be evident. Fever and leukocytosis may also accompany the symptoms.

Most individuals may merely observe periodic discharge or intermittent swelling and discomfort. The process may resolve spontaneously or progress to more obvious drainage, an abscess, and severe pain. Long-standing disease may be associated with the development of squamous cell carcinoma (see later). A critical symptom, bleeding in a sinus that has been present for many years, warrants special attention and surgical intervention.408 An association with condylomata and HIV has also been described with squamous cell cancer.51 Other reported complications of the condition are sacral osteomyelitis, necrotizing fasciitis, toxic shock syndrome, and meningitis.394,408

Treatment

As with other septic processes in the perianal area, antibiotics have little place in the therapy, except possibly as an adjunct to the surgical procedure in a septic or immunocompromised patient. For acute pilonidal abscess, incision and drainage should relieve the patient’s symptoms. Regardless of the size of the septic process, this can usually be accomplished in a physician’s office or in an ambulatory care facility. Whenever possible, it is advisable to drain the abscess and curette or excise the infected sinus simultaneously. The Standards Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons has established certain practice parameters for the performance of ambulatory surgery.363 The following represents their complete statement:

Localized pilonidal abscesses, either primary or recurrent, can usually be incised and drained under local anesthesia in an outpatient setting. For uncomplicated pilonidal sinuses, definitive surgical treatment, including but not limited to excision, curettage, and unroofing, can be accomplished as an outpatient procedure. More complicated surgical procedures, including but not limited to wide excision, creation of skin flaps, and grafting, may require inpatient stay for concern over skin viability or bleeding. Extensive cellulitis in association with pilonidal disease may require inpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy.363

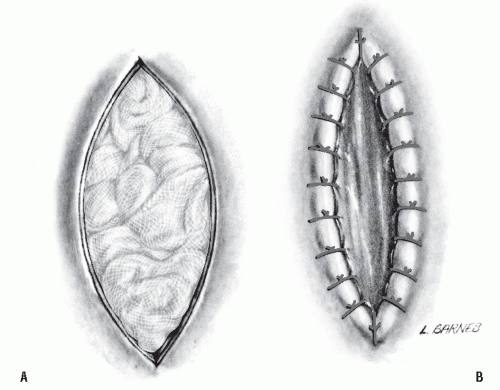

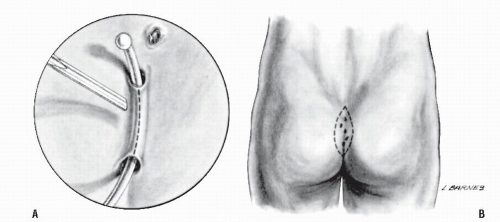

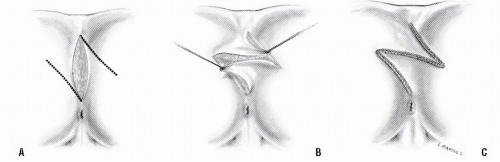

FIGURE 9-15. Excision and packing for the treatment of pilonidal sinus can be accomplished by (A) unroofing of the individual tract or by (B) an all-encompassing excision. |

Definitive elective treatment of pilonidal disease includes excision and primary closure, excision and grafting, excision leaving the wound open to close secondarily, incision and curettage, follicle excision, and cryosurgical destruction.

Drainage with or without Excision.

Incision or excision with drainage is rather simple to accomplish, requires minimal hospital stay, and in fact usually can be accomplished with a local anesthetic in the office. A probe is passed from opening to opening, and the sinus is unroofed (Figure 9-15A). Alternatively, the multiple openings can be excised en bloc, with further extensions or side tracts curetted out (Figure 9-15B). If the procedure is undertaken on an ambulatory basis, the patient is instructed to remove the packing the following morning, usually while taking a bath.

Shpitz and colleagues perform what they term a “controlled excision” by means of loop diathermy.346 The procedure consists of incision and drainage of any pus, followed by excision of diseased tissue and lateral sinuses. With this approach, an expeditious surgical procedure and a shortened or eliminated hospital stay are, in essence, exchanged for a prolonged postoperative convalescence, especially if one is dealing with extensive or deep tissue involvement. All too often, these difficult wounds require frequent treatments, necessitating cauterization, shaving, cleansing, and packing,27,313 although there is a real question whether prophylactic hair epilation reduces the likelihood of recurrence. An approach to dealing with this problem has been suggested by Rosenberg.333 He advocates taping the buttocks apart to flatten the intergluteal cleft during the healing process. However, there is little existing evidence to support the use of antimicrobial agents for chronic wound healing.301

It is not uncommon for pilonidal sinus wounds that extend toward the anal verge to take 6 months or longer to heal (Figure 9-16). Delayed healing may persist to the point where re-excision is advised; multiple operative procedures are frequent sequelae under these circumstances. It is for this reason that one may be reluctant to advise this particular approach except for relatively small sinuses.

A more recent option for the postoperative management of a complex or large pilonidal sinus is vacuum-assisted closure.274 This technique employs a subatmospheric pressure dressing that consists of a foam pad cut to the internal shape of the wound and inserted with a plastic fenestrated tube applied to the center.274 In theory, the vacuum device assists wound contraction by exerting a centripetal force and increases blood flow while reducing edema and tissue bacterial counts.274 Disadvantages include the initial hospital charges, the relative immobility of the patient, and the cost associated with the use of the pump.

LOUIS A. BUIE (1890-1975)

|

Buie was born in Kingstree, South Carolina and received his bachelor’s degree from the University of South Carolina in 1911. He graduated from the University of Maryland Medical School, and after internship in Maryland, he entered the Mayo Clinic as a fellow in surgery. Following service in Italy during World War I, he returned to the Mayo Clinic and, at the request of William J. Mayo, established the section of proctology. A founder of the American Board of Proctology and twice president of the American Proctologic Society, he played a leading role in the development of proctology and, later, of colon and rectal surgery as a specialty in the United States. Other contributions included designs of a sigmoidoscope, proctoscopic table, and biopsy forceps. In addition, he authored or coauthored three texts on proctology and was a founder of the journal Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, serving as its editorin-chief from 1957 to 1967. An international authority in the field, he was perhaps best known for his writings and treatment of pilonidal sinus.

Marsupialization.

Excision with marsupialization is a compromise between a completely open wound and a completely closed one. This approach was initially described by Buie in 1937 and amplified later in his article on “jeep disease.”65 This operation permits a somewhat smaller opening than does the technique in which the wound is left totally open (Figure 9-17). If the catgut or long-term absorbable suture succeeds in holding the edges together, more rapid healing should occur. Unfortunately, the sutures frequently pull out, and the individual is left with as wide a wound as would have resulted had excision and packing been employed. Even without this complication, the wound still requires careful attention, including packing, perhaps shaving, cauterization and cleansing.

Oncel and coworkers undertook a prospective, randomized study in which 40 consecutive patients with “limited, chronic pilonidal disease” were operated on with either excision or marsupialization.302 Operation time, hospital stay, and time lost from work were all shorter in the former group. Furthermore, patient satisfaction was significantly greater in this group, primarily because the procedure was undertaken on an outpatient basis.

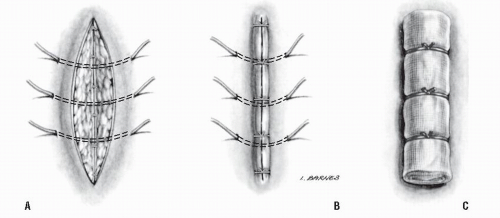

Excision with Primary Closure.

Excision with primary closure can be performed in an ambulatory surgical facility if the sinus is relatively small. However, for more extensive lesions, inpatient therapy is recommended. This approach has the disadvantage of a relatively prolonged hospital stay, but it provides the potential benefit of a healed wound within perhaps 10 to 14 days. For large, complex pilonidal sinus problems, particularly when multiple procedures have been previously performed (see Figure 9-16), the excision and primary closure technique may be very effective.

The pilonidal sinus is excised to the gluteal fascia (Figure 9-18A). The fascia is incised, and a periosteal elevator is used to lift the fascia off the sacrum (Figure 9-18B). This maneuver permits the placement of heavy retention sutures through all layers. These are laid into position, and the fascia is reapproximated with absorbable suture material (Figure 9-19A). The wound is copiously irrigated, and the skin is closed (Figure 9-19B). The retention sutures are secured over a stent dressing, and the dressing is left in place for approximately 10 days (Figure 9-19C). When the pilonidal sinus extends near the anal opening, it is better to

confine the bowels for several days. This requires a clear liquid diet and the use of a bowel-confining regimen—deodorized tincture of opium, diphenoxylate hydrochloride, and codeine.

confine the bowels for several days. This requires a clear liquid diet and the use of a bowel-confining regimen—deodorized tincture of opium, diphenoxylate hydrochloride, and codeine.

FIGURE 9-18. The first two steps in the primary closure technique for the treatment of pilonidal sinus infection. A: The fascia is incised. B: The fascia is elevated. |

Excision with Grafting.

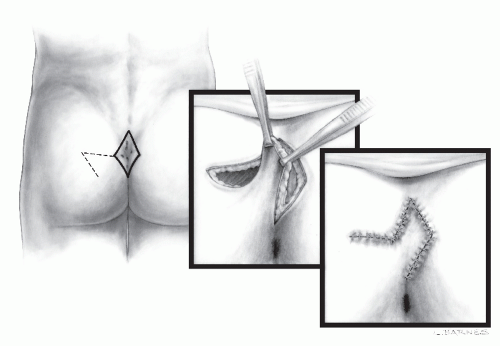

With considerable skin loss, as may occur following multiple operations, or as a primary procedure, it is sometimes useful to rotate skin flaps to cover the resultant wound defect.181 This can be performed using the principles described in Chapter 11; advancement or rotation flaps (see Anoplasty for Severe Stenosis); or even, as has been suggested, by means of a gluteus maximus myocutaneous flap.311 To eliminate the deep natal cleft and the conventional vertical wound, which tends to pull apart, some surgeons recommend a Z-plasty.52,225,264,273,281,282 and 283,382 Others suggest excision in a rhomboid fashion, with coverage effected by means of a so-called Limberg buttock flap (Figure 9-20).17,381,391 Another modification of the rhomboid flap design is the socalled Dufourmentel technique.265 In the Z-plasty, the depth of the intergluteal fold with the associated pilonidal sinus disease is excised; skin flaps are then mobilized, rotated, and interdigitated (Figure 9-21).

FIGURE 9-21. Treatment of pilonidal sinus by Z-plasty. A: Incisions outlined. B: Skin flaps rotated. C: Primary closure obliterates the natal cleft defect. |

Karydakis described a technique for limiting the likelihood of recurrence following excision of pilonidal sinus by means of a variation of excision with primary closure and grafting in more than 6,000 patients.220 By this technique, each sinus is completely excised through a vertical, eccentric, elliptical incision. A thick flap is created by undermining the medial edge and advancing it across the midline so that the whole suture line is lateralized in order to reduce the risk for recurrence.228

Sinus Extraction.

The importance of avoiding the creation of a midline incision has been emphasized by Lord and Bascom.31,32,259 This approach consists of lateral drainage of the abscess, removal of the hair, and excision of the hair follicle (if present). Minimal excision of a sinus tract may be performed. The cavity is cleansed through incisions adjacent to but not inside the pilonidal sinus. The cavity walls are not excised but are permitted to collapse. The procedure may be carried out in the office or at an ambulatory surgical facility. An alternative approach is to drain the acute abscess and allow the infection to subside before follicle removal is attempted.32 According to Bascom, the enlarged follicles should be excised individually, leaving only small midline wounds, 2 to 4 mm in diameter (Figure 9-22).32 Alternatively, these may be closed primarily to reduce healing time.

This technique may be analogous to that of the management of a “horseshoe” fistula, in which one endeavors merely to remove the crypt-bearing area and establish adequate drainage. Certainly, if one can accomplish this satisfactorily, healing will result with minimal deformity. The same “less is more” approach appears equally valid for selected instances of pilonidal sinus.

Sclerosing Injection.

Hegge and colleagues suggest a “conservative” approach to the treatment of pilonidal disease, injection of phenol (80%) into the sinus tract.186 The procedure was carried out on 48 patients after they had undergone minimal drainage and hair removal. They were considered cured if there was no evidence of recurrent disease within 1 year of treatment. The authors reported a low recurrence rate—only 6.3%.

Cryosurgery.

The use of cryosurgical destruction has also been advocated in the surgical management of pilonidal sinus.168,297 The technique consists of surgery (opening of the tracts and side branches), curettage, and electrocoagulation of bleeding points. The open wound is then sprayed with liquid nitrogen for approximately 5 minutes.

We have had no experience with this technique, but O’Connor has stated that there is less deformity and scarring than with a wider excision.297 However, because it has been generally recognized that a wide excision is not a necessary part of the treatment, the comparison may be inappropriate.

Nonoperative Management.

As previously mentioned, the military has been quite concerned about the lost time associated with the surgical management of pilonidal sinus and its adverse consequences. Armstrong and Barcia examined the role of conservative, nonoperative treatment of pilonidal sinus disease at an army community hospital.26 Complete healing

over 83 occupied bed days was observed in 101 consecutive cases managed through meticulous hair control by natal cleft shaving, improved perineal hygiene, and limited lateral incision and drainage for abscess. This was compared with 4,760 occupied bed days in 229 patients who had undergone 240 operative procedures during the previous 2 years. The prolonged hospitalization was explained by the army basic trainee population, who, by regulation, could not be discharged from the hospital until they were fit for duty. The authors further observed that with the application of conservative treatment over 17 years, only 23 excisional operations were performed.

over 83 occupied bed days was observed in 101 consecutive cases managed through meticulous hair control by natal cleft shaving, improved perineal hygiene, and limited lateral incision and drainage for abscess. This was compared with 4,760 occupied bed days in 229 patients who had undergone 240 operative procedures during the previous 2 years. The prolonged hospitalization was explained by the army basic trainee population, who, by regulation, could not be discharged from the hospital until they were fit for duty. The authors further observed that with the application of conservative treatment over 17 years, only 23 excisional operations were performed.

Results of the Various Methods of Management

It is interesting to note that almost irrespective of the method of treatment applied, very few patients are troubled with symptoms of persistent pilonidal sinus disease beyond the age of 40 years. Perhaps one simply outgrows the condition. It is therefore important to understand that ultimate cure is an almost inevitable result when one compares the value of the various surgical alternatives. Another problem with analyzing the data is that there are very few so-called prospective, randomized, controlled studies that can survive critical review. One such report by Füzün and colleagues randomly compared primary closure with excision in 110 consecutive patients.165 Although primary closure was associated with hospital stays significantly longer than those in the opentreatment group, the patients returned to work earlier. The primary closure group also had an increased risk for infection and a higher recurrence rate (4.1% vs. 0%). The authors concluded that both treatments have their place. Therefore, the recommendation should be based on individual preference, especially employment status. Others concur in uncontrolled studies that the primary advantage of the closed techniques over open drainage is more rapid recovery, but this must be balanced against the risk of infection.304,362

Incision or Excision and Drainage.

Hanley has been an advocate of emergency surgery for acute pilonidal abscess by excision and open treatment.183 With this technique, he reported uniform healing with no evidence of recurrence in a small group of patients. Jensen and Harling performed simple incision and drainage of 73 consecutive individuals who presented with an acute pilonidal abscess.208 Healing per primam occurred in 42 (58%) within 10 weeks. The recurrence rate following initial primary healing was, however, 21%. The authors further observed that those with fewer pits and lateral tracts had a statistically significantly better chance of healing primarily. There is agreement in all current writings that wide excision of all tissue down to the sacrum, leaving the wound to heal by granulation, cannot be justified.15

Excision and Marsupialization.

This is still one of the most commonly employed options for the treatment of pilonidal sinus. Solla and Rothenberger reported that 125 of their 150 patients were managed.361 The average healing time was 4 weeks, with 3 individuals requiring up to 20 weeks for closure. The recurrence rate was 6%, all ultimately healing following remarsupialization. Karakayali and colleagues compared clinical outcomes in a randomized, prospective study of marsupialization versus rhomboid excision and Limberg flap in 140 consecutive patients. They concluded that the former approach provides more clinical benefits with respect to convenience but is associated with more inconvenience as to wound care and healing time than rhomboid excision and Limberg flap.219

Excision with Primary Closure.

Zimmerman reported outpatient excision and primary closure in 32 patients.418 Follow-up was for a mean of 24 months. In all cases, primary healing was obtained, a result that is not dissimilar to my own experience. In addition, Obeid noted primary healing in all 27 individuals managed by a modification of the primary closure technique illustrated in Figures 19-18 and 19-19.296 Kronborg and colleagues reported the results of a randomized trial of treatment by one of three methods: excision, excision with suture, and excision with suture and antibiotic coverage with clindamycin.239 Recurrence rates were, respectively, 13%, 25%, and 19%. As expected, healing was much quicker after primary suture than after excisional therapy alone (median, 14 days vs. 64 days). Tritapepe and Di Padova reported 243 consecutive patients who underwent excision and primary closure with the use of a closed-suction drain for 24 hours, followed by wound irrigation with an antiseptic solution.386 With a follow-up of 5 to 15 years, there were no wound breakdowns and no recurrences.

Petersen and colleagues undertook a meta-analysis of data published over a period of 35 years with various primary closure techniques.312 Seventy-four publications included a total of 10,090 patients. These investigators concluded that there appears to be a significant benefit with respect to healing when the asymmetric-oblique closure or the full-thickness flap technique is employed when compared with midline closure.312

Excision and Grafting.

Reports of the success of excision and grafting are somewhat difficult to interpret in light of the lack of a control in these studies.181,264 In the report from the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, 58 patients were reviewed who underwent extensive or recurrent pilonidal disease surgery with primary skin grafting.181 More than 72% had recurrent disease when initially seen. The average hospital stay was 10 days, and the time lost from work averaged 28 days. The recurrence rate was 1.7%, and the failure rate was 3.4%. Using the Z-plasty technique, Mansoory and Dickson treated 120 patients.264 There were two recurrences, a very favorable experience. Alver and colleagues reported 35 selected individuals with “small and moderate extent disease” treated by the fasciocutaneous Limberg flap method.17 The rate of wound infection or dehiscence was 17%, with all individuals ultimately healing. Urhan and coworkers initially reported 110 Limberg flap procedures with five recurrences (4.9%),391 with no further failures when 90 later patients were added.381 Manterola and colleagues used the similar Dufourmentel technique in 25 patients and noted two instances of infection or dehiscence.265 Kitchen reported 141 patients treated by the Karydakis operation and noted a recurrence rate of 4%.228

When skin is lost as a consequence of pilonidal sinus disease, particularly in the recurrent situation, mobilizing skin to cover the defect will more reliably lead to a satisfactory result. Bascom reported 30 patients with open midline wounds from recurrence.33 All healed by closure of the natal cleft through the raising of skin flaps.

During the past decade, the literature is replete with techniques on the treatment of pilonidal sinus, almost exclusively using either one of the primary closure methods, with or without skin mobilization, or some modification of a Bascom-like minimal procedure. Almost all are nonrandomized

publications of an individual surgeon’s experience or that of his or her group. A few references are cited here for the convenience of the reader.4,20,44,118,146,237,258,263,285,378

publications of an individual surgeon’s experience or that of his or her group. A few references are cited here for the convenience of the reader.4,20,44,118,146,237,258,263,285,378

Sinus Extraction (Lord-Bascom Procedure).

Bascom and Edwards reported their experiences with the Lord treatment: removal only of the follicles and hairs.31,135 In an earlier report, 50 patients were treated in the office, and local anesthesia was used. Acute abscesses were treated by excision of the enlarged follicles from the midline skin. One to 10 follicles were removed, individually if possible. Because incisions were kept smaller than 7 mm, the specimens weighed less than 1 g per patient. Follow-up averaged 24 months. The mean disability was 1 day, and the mean wound healing time was 3 weeks. Recurrences appeared in four patients (8%); all were healed 3 weeks following reoperation. There was no incident of a second recurrence. A later publication by Bascom of 161 patients treated revealed comparable results.32

Edwards reported 102 patients treated by this technique.135 The median number of days lost from work was 10, and the median number of days requiring healing was 39. Eightynine percent of these patients were free of recurrent disease provided they attended the follow-up clinic. Because some patients failed to attend, it is difficult to interpret the results of this study. It appears, however, that the author was not as successful as Bascom.

Senepati and associates performed 218 Bascom’s operations as day cases.343 Ten percent developed recurrences requiring reoperation. Theodoropoulos and colleagues opine, based on their experience with this operation in a military hospital, that this operation is safe, with minimal morbidity, and can be reliably used as a second-line alternative for recurrent disease.379

Gips and colleagues reported the use of a trephine technique to accomplish a limited procedure in 1,358 patients. Each crypt opening was cored out with the use of Keyes trephines of various diameters. The recurrence rate was 6.5% at 1 year and 11.5% after 4 years.172

Meta-analysis of Results.

Brasel and coworkers undertook a meta-analysis comparing healing by primary closure techniques with that of open healing in randomized controlled trials.55 Eighteen trials were included. They concluded that wounds heal more quickly after primary closure than after open healing but at the expense of increased risk of recurrence. They recommend that off-midline closure should become the standard management for pilonidal disease when closure is desired.55

ALFRED-ARMAND-LOUIS-MARIE VELPEAU (1795-1867)

|

A native of Brèches, Indre-et-Loire, Velpeau was a student and assistant to Pierre Bretonneau. During his early medical career, he was a surgeon in several hospitals in Paris. In 1833, he succeeded Alexis de Boyer as chair of clinical surgery at the University of Paris, a position he maintained until his death in 1867. He was a skilled surgeon and renowned for his knowledge of surgical anatomy. He published more than 340 titles on surgery, embryology, anatomy, obstetrics, and other subjects, and in 1830, he wrote an important book on obstetrics, entitled Traité elementaire de l’art des accouchements. In 1827, he is credited for providing the first accurate description of leukemia. The eponymous “Velpeau bandage” that is used for arm support is named after him. There are several other medical terms named after him; however, these are now primarily used for historical purposes, including Velpeau hernia for the femoral hernia, Velpeau’s disease for hidradenitis suppurativa, Velpeau’s canal for the inguinal canal, and Velpeau’s fossa, which is the ischiorectal fossa. Despite being one of the top surgeons in his time, Velpeau believed that pain-free surgery was a fantasy, and that surgery and pain were inseparable. With the advent of the anesthetics ether and chloroform in the 1840s, Velpeau was amazed, saying “On the subject of ether, that it is a wonderful and terrible agen[t]; I will say of chloroform, that it is still more wonderful and more terrible.”

Comment.

It is now generally agreed that minimal surgery should be applied to the treatment of pilonidal disease whenever possible. The concept of Lord and of Bascom in removing the hair follicles and the hairs themselves without extensive excision and debridement is an excellent one. Every attempt should be made to keep the patient out of the hospital and to limit the morbidity of the procedure. However, there are some individuals who will benefit from a more generous excision, particularly those who have undergone multiple procedures or have extensive disease. Under these circumstances, inpatient hospital treatment with excision and primary closure, with or without grafting, may offer a lower morbidity, shortened convalescence, and more rapid healing.

Pilonidal Sinus and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in pilonidal sinus tracts, almost all inevitably involving longstanding active inflammation. Fasching and colleagues reviewed 36 cases that they identified in the literature.151 As of 1996, there were 44 reported.112 Treatment consisted of wide excision and grafting. This is similar to the management of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin anywhere in the body that can lend itself to this approach. More recently, it has been suggested that because of the high recurrence rate of the malignancy, consideration should be given to adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation.112,241

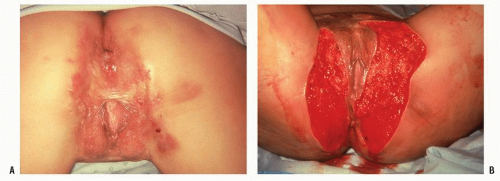

Suppurative Hidradenitis (Hidradenitis Suppurativa)

Suppurative hidradenitis is an uncommon, chronic, recurrent, indolent infection involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue arising in the apocrine glands (i.e., axillary, inguinal, genital, perineal, and mammary). The most frequent area of involvement is the axilla. The condition was originally described in 1839 by Velpeau.395 The overall incidence is higher in women, with most cases occurring between the ages of 16

and 40 years, but most studies of operated cases affecting the perineum indicate a larger number of men.

and 40 years, but most studies of operated cases affecting the perineum indicate a larger number of men.

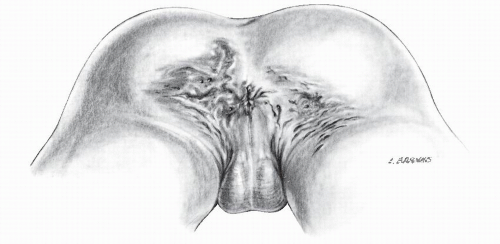

FIGURE 9-23. Artist’s concept of suppurative hidradenitis with extensive involvement of perianal area and buttocks. |

Etiology

Suppurative hidradenitis does not occur before puberty because it is believed that the effect of sex hormones on the apocrine glands is the inciting factor. An androgen-based endocrine disorder has also been postulated. Harrison and colleagues demonstrated an androgen excess and a progesterone decrease through detailed hormonal profiles in 36 women and 14 controls.184 The proposed mechanism for the possible role of androgens being associated with suppurative hidradenitis lies in end organ sensitivity, rather than in absolute plasma levels. Although the etiology is unknown, acne appears to be a predisposing factor, with stress, poor skin hygiene, obesity, excessive heat, hyperhidrosis, and chemical depilatories possibly playing a role.94 There has been no documentation of an increased association with diabetes mellitus, but impaired glucose tolerance has been observed. There may be a genetic predisposition based on an increased familial incidence. Some observe an increased frequency in those with Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome, herpes simplex, certain kinds of arthritis, and a number of other conditions. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing suppurative hidradenitis has been reported in at least 16 cases,21,62,128,277,416 with one-half of these patients dying of metastatic disease.

Pathophysiology

Suppurative hidradenitis commences with obstruction of the hair follicle rather than the apocrine gland duct. This is due to a defect in terminal differentiation that impedes follicular epithelial shedding.415 After follicular keratinocyte multiplication occurs, folliculitis proceeds to occlude the apocrine gland duct with resultant inspissated secretions. The gland may then rupture, which can lead to extension of the process into the dermis, with consequent secondary involvement of other glands and ducts. In rare instances, the process can extend through the fascia into the underlying muscle.

Differential Diagnosis

The condition may be confused with anal fistula, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, pilonidal sinus, infected sebaceous cyst, furunculosis, granuloma inguinale, lymphogranuloma venereum, and other infections in the anal area.

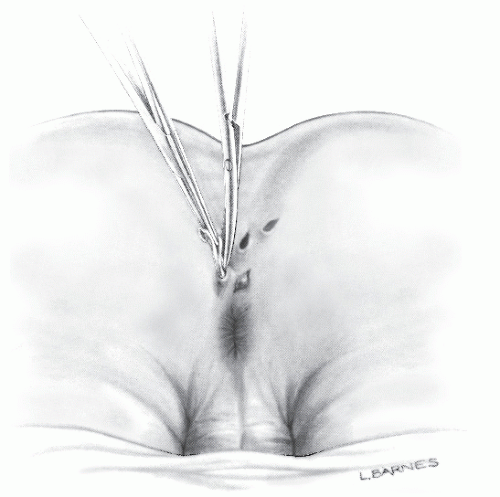

Physical Examination

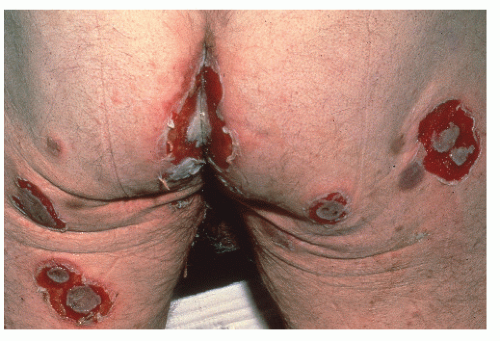

Examination reveals painful, tender, erythematous, purulent lesions (Figure 9-23). These may be associated with adenopathy and systemic signs (i.e., fever, malaise, leukocytosis). The condition frequently produces burrowing sinuses that can extend for many inches around the anus, into the scrotum, buttocks, labia, medial thighs, and sacrum (Figures 9-24 and 9-25).

Although the tracts are usually relatively superficial, they can actually invade deeply and extend to involve the area around the femoral vessels. Urethral and rectal fistulas have been noted, but these are more likely caused by aggressive surgery rather than aggressive disease.

Although the tracts are usually relatively superficial, they can actually invade deeply and extend to involve the area around the femoral vessels. Urethral and rectal fistulas have been noted, but these are more likely caused by aggressive surgery rather than aggressive disease.

FIGURE 9-24. Suppurative hidradenitis with extensive perianal sinuses may be confused with horseshoe fistula or Crohn’s disease. |

Histopathology