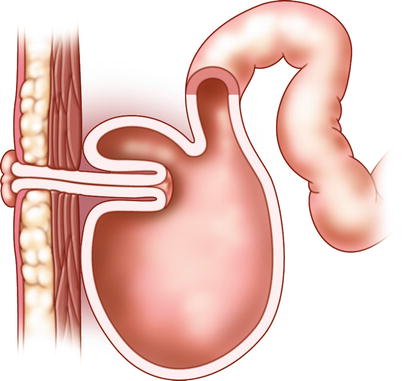

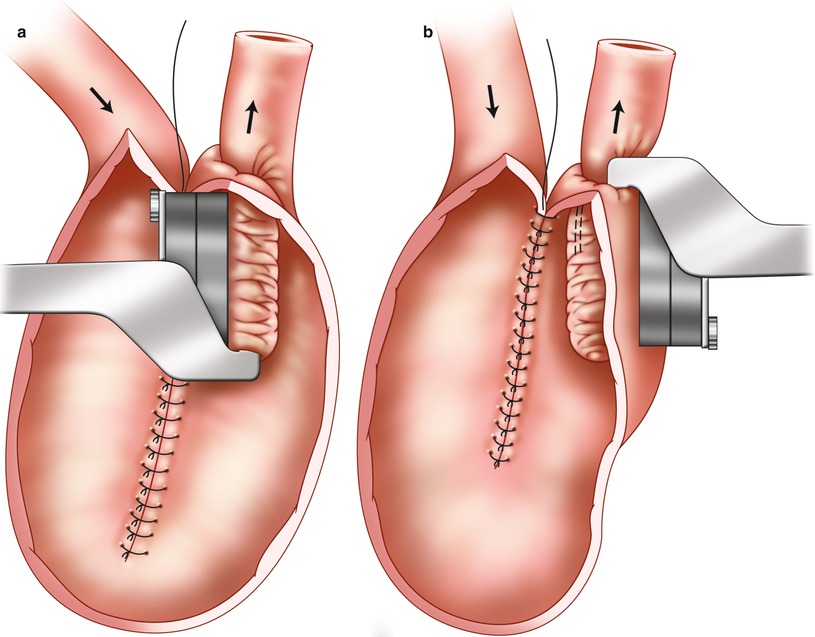

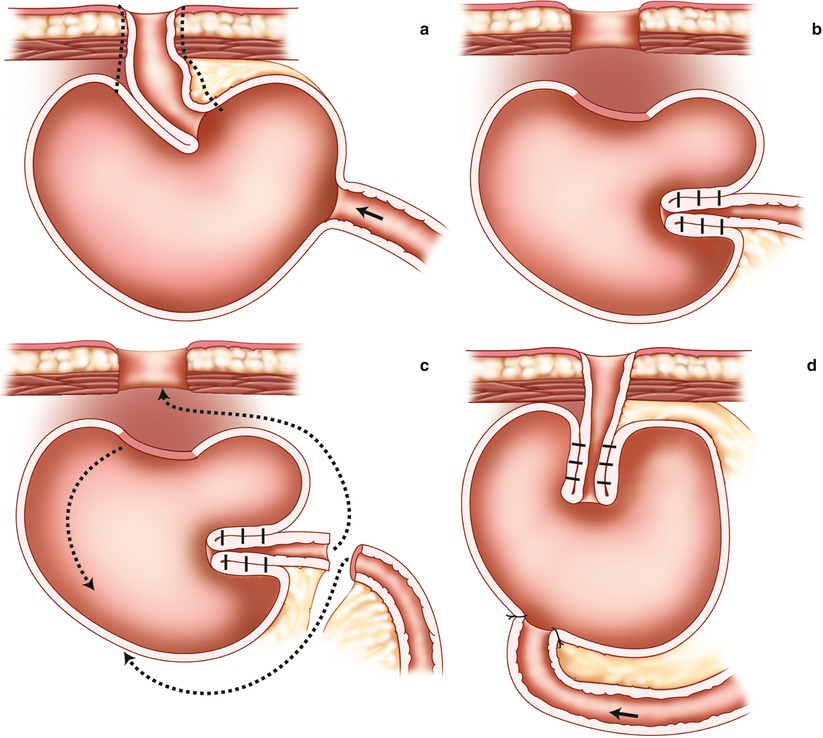

Fig. 10.1

The original procedure (a) Segment of terminal ileum (Arrow points to distal) (b) Folding of the bowel on itself and formation of the posterior wall. (c) Creation of the anterior wall of the pouch. (d) Completed pouch

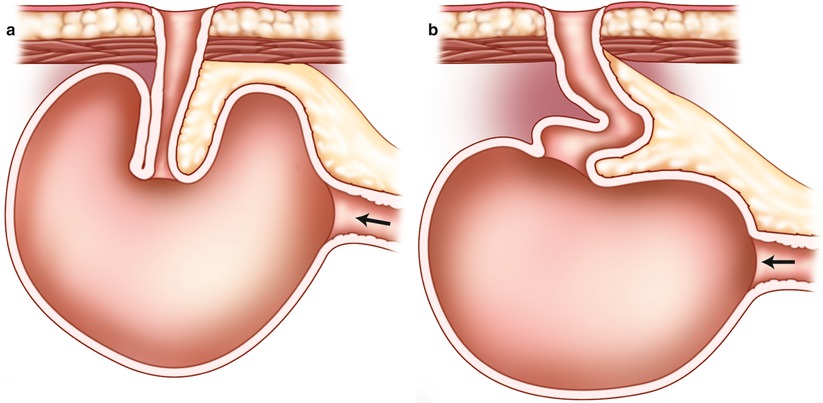

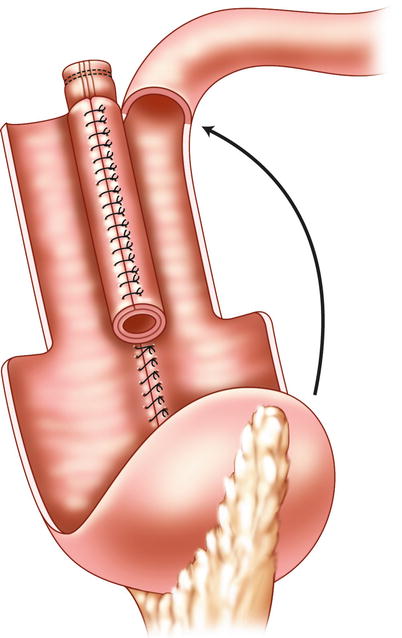

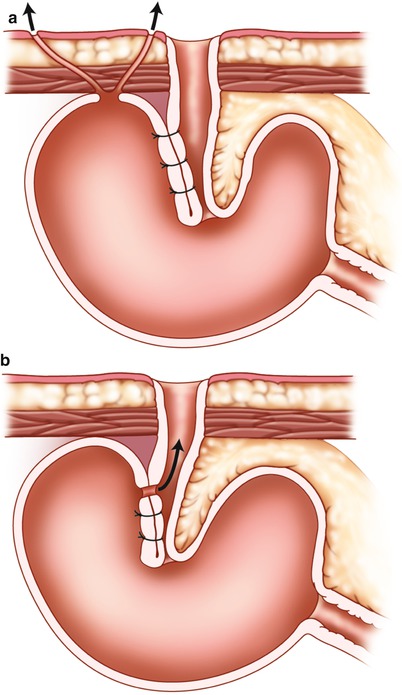

Fig. 10.2

The Kock reservoir with nipple valve

In the 1970s and 1980s, the continent ileostomy gained popularity mainly in the USA and Canada, as well as in Europe—predominantly in Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Several modifications, such as the Barnett continent ileostomy and the T-pouch, have since evolved over the years. While the basic principle for the pouch construction is identical with the Kock pouch, the techniques used to achieve continence differ markedly.

Sir Alan Park used the ileal reservoir developed by Kock for endoanal anastomosis with preservation of the sphincter mechanism and published the first results on “restorative proctocolectomy” in 1978 [3]. This method is at present the preferred option worldwide for the surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis, and the demand for continent ileostomy is considerably reduced. However, the continent ileostomy continues to be routinely performed in a few specialized centres and other surgeons are often called upon to evaluate patients with troublesome continent ileostomies. The goals of this chapter are therefore to provide insight into the evaluation and management of potential complications associated with these pouches and allow surgeons to be more comfortable in caring for patients with continent ileostomies.

The Kock Pouch

Formation of the Ileal Pouch

Key Concept: Pouch construction uses terminal ileum for formation, with several different configurations.

The ileal pouch constructed according to the Kock original technique has proved to be an intestinal reservoir well designed to eliminate intraluminal pressure at filling and allowing to expand on distension. It has been convincingly demonstrated that the “double-folded” technique used offers a final pouch volume significantly larger than in pouches where the detubularized segment is folded side-to-side only [4, 5]. The reservoir will gradually reach a volume of 400–600 ml, a volume that will keep the number of evacuations to about three per day. For construction as suggested by Kock [6], 45 cm of the terminal ileum is sufficient—15 cm for the pouch outlet and nipple valve and 30 cm for the formation of the reservoir—while other authors [7], preferring a three-limb ileal pouch, use a significantly longer segment of the terminal ileum for construction, though no improvement in function or in complication rate can be demonstrated.

Although the “nipple valve” was a promising technique to preserve continence, failures were common. When the reservoir distends, it stretches on the mesentery and puts stress on the valve. Over time, the valve may become reduced or finally disappear, leading to intubation difficulties and incontinence problems (Fig. 10.3). The method had to be changed several times over the years, until a stapling technique was introduced that ultimately has provided promising results. Nevertheless, the main problem in regard to the Kock pouch construction is the nipple valve construction, which remains “the Achilles heel” of the procedure to this day.

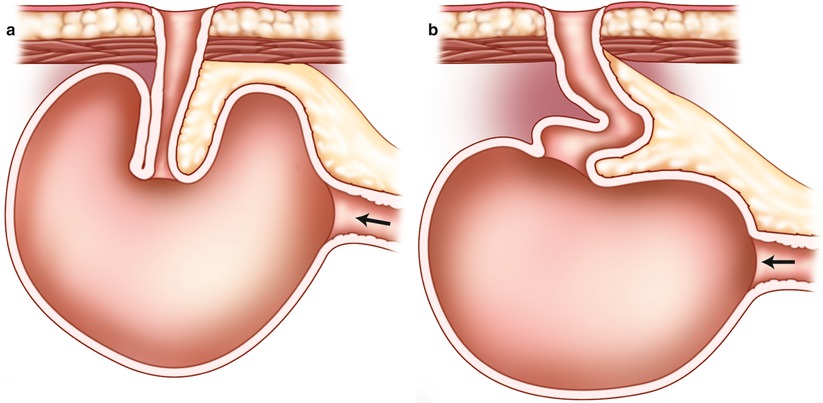

Fig. 10.3

Nipple valve sliding. (a) Arrow points to afferent limb. (b) The nipple valve has disappeared leading to intubation difficulties

Formation of the Nipple Valve

Key Concept: While the nipple valve is the most difficult portion of the pouch construction, several technical points will minimize complications.

For a safe stabilization of the nipple valve, special attention and care should therefore be given to the following measures:

Stripping of the peritoneal leaves and “defattening” of the nipple valve segment are important measures to reduce the bulk of tissue interposed in the intussusception (Fig. 10.4).

Fig. 10.4

Mesenteric stripping

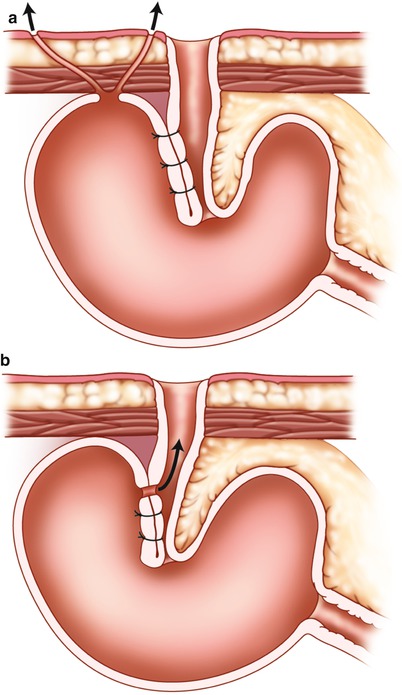

The nipple valve should be stabilized by means of four staple rows: one staple row on each side of the mesentery, one on the antimesenteric side, and—to further prevent sliding and prolapse—one staple row anchoring the nipple valve to the wall of the reservoir (Fig. 10.5). To avoid necrosis of the tip of the nipple valve, removal of ten staples near the hinge of the stapling device is an important precaution.

Fig. 10.5

Stapling and anchoring of the nipple valve to the reservoir wall. (a) Stapling of the nipple valve. (b)Anchoring the valve to the reservoir wall

Moreover, a careful and correct construction of the exit conduit channel with firm anchoring of the reservoir to the abdominal wall is necessary.

Strict adherence to routines in the early postoperative management of the pouch—extending the drainage period in a gradual fashion for about 4 weeks—is another important measure contributing to stabilization of the nipple valve. Although detailed instructions on the postoperative care of the continent ileostomy have been given extensive space in many recent articles, the importance of this last point has often been neglected.

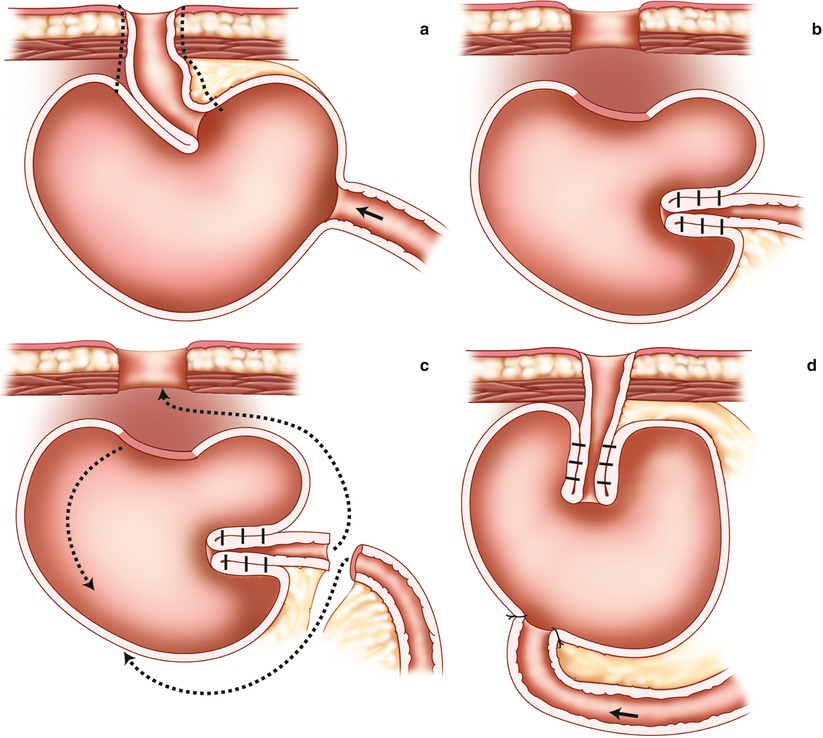

The T-pouch is an alternative technique developed to replace the troublesome nipple valve [8, 9]. A unique antireflux mechanism is created by anchoring an isolated ileal segment as an outlet between the two limbs of the bowel “U”, which will form the reservoir (Fig. 10.6). Results have been reported in a 10-year follow-up study [10], demonstrating an acceptable rate of complications and excellent functional results. Unfortunately, the technique is difficult and the procedure has yet to reach wide acceptance for faecal diversion.

Fig. 10.6

The T-pouch

The Barnett continent intestinal reservoir is another modification of the Kock pouch procedure. In this configuration, the afferent limb of the small bowel is used to construct the nipple valve and outlet. To improve continence, an intestinal segment with its lumen remaining in continuity with the pouch is wrapped as an intestinal collar around the base of the nipple valve, similar to a gastric fundoplication [11]. Collective results from five hospitals revealed similar complication rates and failures as with the traditional types of continent ileostomy commonly used [12, 13]. The procedure is complicated and the Barnett pouch has also not received general acceptance. The importance of this modification is still scientifically unproven.

Complications and Their Management

While there have been keen advocators for the continent ileostomy over the years, many surgeons have been reluctant to adopt the method considering the high postoperative morbidity—despite modifications in surgical technique and postoperative management.

Early Complications

Key Concept: Early complications with the continent ileostomy are similar to any other bowel surgery.

With increasing experience on the part of surgeons, the early morbidity rate in terms of anastomotic leaks with peritonitis and/or intra-abdominal abscess, fistulas, and wound sepsis and dehiscence has been markedly reduced. Intestinal obstruction, local abscess, necrosis of the nipple valve, and fistula are reported to occur in about 10 %.

Late Complications

Key Concept: Most of the complications developing later in the postoperative course are related to the nipple valve, and the success of the operation stands with the competence and stability of this intussusception.

Late complications with pouch operations include those that are similar to any other bowel surgery, such as obstruction, stricture, and hernia. However, continent ileostomies have a unique set of late complications that are often related to the nipple valve including:

The collective results imply that revisional surgery due to any of the above-mentioned defects has decreased from 40 to 50 % with the early techniques to about 20–25 % with the introduction of the currently most popular method of mesenteric stripping and stapling of the nipple valve. The need for reoperations has decreased significantly with increased experience of the surgical team to below 10 % [6, 18, 20, 21]. In concordance with the reduced rate of complications, surgical experience, and success of revisional surgery, the failure rate has decreased significantly and is currently reported between 4 and 10 % [6, 14, 17, 20–24], a failure rate which is comparable to that after restorative proctocolectomy [25–29].

Management of Complications

Key Concept: The continent ileostomy is a demanding procedure with a high potential for complications, and special skill and experience are required for their recognition and management.

Early Complications

Local or diffuse peritonitis reflecting suture leakage or abscess require immediate and proper treatment. A local peritonitis with or without abscess should be drained. It is usually best to establish a loop ileostomy proximal to the affected area.

A fistula either may heal spontaneously on this treatment or could be subject to revision by another operation 2 or 3 months later.

Ischemic necrosis of the pouch outlet and/or the nipple valve may also occasionally develop in the early postoperative phase, a vascular complication mostly due to a faulty technique. Depending on its extension of the ischaemia, it may be successfully treated either conservatively by prolonged tube drainage of the pouch or, when more extensive as judged, by ileoscopy and be primarily managed by establishment of a defunctioning loop ileostomy. In both situations, revisional surgery may then be performed at a convenient time a few months later.

Bleeding within the pouch during the first postoperative days is common, and the irrigation fluid will sometimes be heavily bloodstained. Profuse bleeding may sometimes occur, even after a careful suturing, with clots accumulating in the pouch blocking the draining catheter. Too little attention has been directed to the importance of the postoperative wide-bore (28Fr) catheter drainage. With strict irrigation routines and the use of a proper draining system, this complication should in most cases be possible to manage conservatively.

The importance of a defunctioning ileostomy for reducing the early morbidity rate, or at least minimizing the consequences of any complication developing during the early postoperative phase, may be controversial; however, such a safety measure should probably be recommended for the beginners before experience has been gained.

Late Complications

Key Concept: Despite surgical experience, improvements in technique, and strict routines in the postoperative care, sliding or prolapse of the nipple valve, or a nipple valve fistula, may develop resulting in incontinence and a need for surgical intervention.

Late complications typically manifest in predictable ways, and most involve problems with the nipple valve itself. In this section we will walk you through how to approach these often difficult situations.

Sliding of the Nipple Valve and Its Correction

Key Concept: Nipple valve sliding presents with problems with pouch intubation. While temporizing measures are possible, this most often requires formal operative revision.

Intubation difficulties of the reservoir and/or leakage of gas and faeces are symptoms indicating nipple valve sliding (Fig. 10.3). Confirmation of a defect valve can be done by using a flexible endoscope. In this context it should be mentioned that patients may sometimes present acutely with an over-distended reservoir due to inability to insert the catheter. The problem can be solved by using a small-size rigid sigmoidoscope (i.e. children’s sigmoidoscope), by which it is possible to follow the typically angulated course into the reservoir under direct vision. An indwelling catheter can then be passed through the sigmoidoscope and left in place.

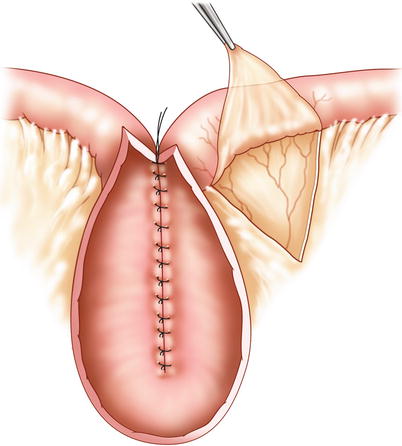

Revisional surgery through a formal laparotomy is required for reestablishment of continence in most cases, however. The surgical approach to be employed depends on the precise findings at laparotomy. The stoma and outlet is first dissected free and the reservoir mobilized into the wound. After opening the pouch, it may occasionally be possible to de-invaginate the intussusception simply by careful dissection and separation of layers of the nipple valve. Provided that the segment is sufficiently long, a nipple valve is reconstructed and fixed in position according to established technique. In most cases, however, the outlet segment is damaged by the dissection or insufficient in length and has therefore to be sacrificed. A new nipple valve and outlet has to be constructed, a procedure that can be done by two different techniques.

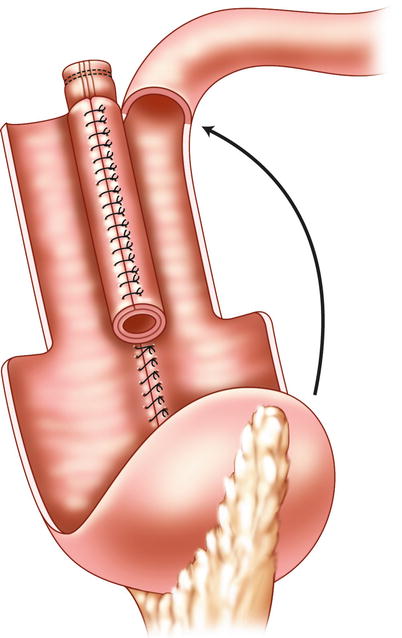

The most common technique is to sever the entrance conduit 15–20 cm from the reservoir. After peritoneal stripping and “defattening” of mesentery of the segment that is still attached to the pouch, the new nipple valve is fashioned and stabilized according to the stapling techniques described. The reservoir is then rotated to enable the new outlet to be passed through the abdominal channel, allowing a new stoma to be formed (Fig. 10.7). Special attention should be directed to the firm anchoring of the pouch to the abdominal wall. The channel through the abdominal wall should either be narrowed to fit the outlet properly, or when not possible, a new trephine wound should be created at another site of the abdominal wall.

Fig. 10.7

Reconstruction of the nipple valve on the efferent loop and rotating the reservoir. (a) Line of dissection and resection along the efferent limb. (b) Recreating the nipple valve. (c) Rotation of the pouch in the direction of the arrows. (d) Completed reservoir

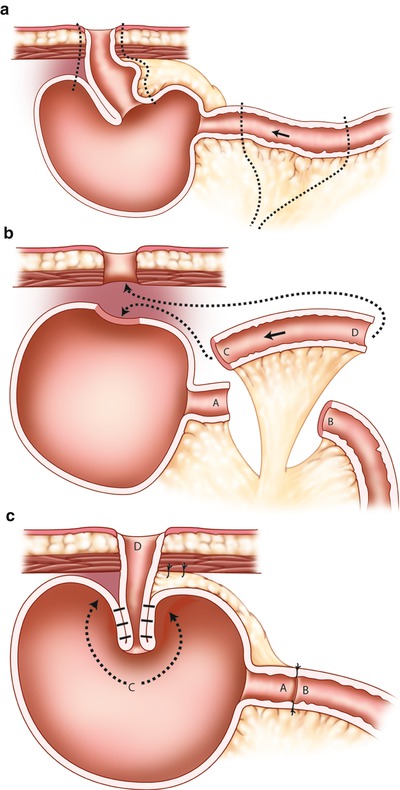

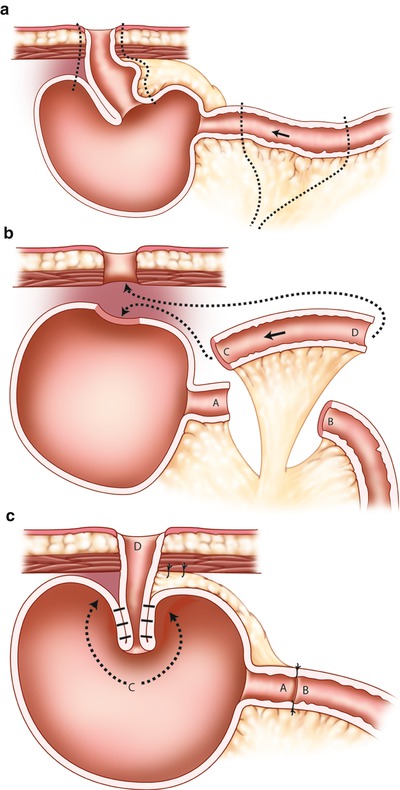

Another alternative procedure for construction of a new pouch exit conduit and nipple valve is to isolate a 15–20 cm segment of the ileum at a convenient level above the reservoir and interpose the segment between the reservoir and the abdominal wall (Fig. 10.8).

Fig. 10.8

Reconstruction of the nipple valve by interposition of a new outlet segment between the reservoir and the abdominal wall. (a) Line of dissection along nipple valve and afferent limb. (b) Resection of the original nipple and construction of new segment (C-D) for the nipple (arrows demonstrate rotation). (c) Completed reconstruction

Prolapse of Nipple Valve

Key Concept: Prolapse is typically from the abdominal wall passage becoming too wide and normally requires surgical revision.

Although a prolapse can often be temporarily restored manually, surgical revision by laparotomy will be required for lasting cure. It should be mentioned that prolapse of the nipple valve occurring during pregnancy can be easily reduced manually and mostly resumes to normal after delivery. A common underlying cause of the prolapse is that the channel through the abdominal wall has become too wide. The stoma and exit conduit should therefore be dissected free with complete mobilization of the reservoir. The channel should be narrowed by suturing the rectus muscle and the fascia, allowing the exit conduit to fit snugly. An alternative is to select another site for the ileostomy and create a new trephine wound through intact abdominal wall. Anchoring the nipple valve by stapling it to the wall of the reservoir has contributed greatly to prevent nipple valve dislocation (Fig. 10.5).

Parastomal Hernia

Parastomal hernia is rare but should be treated according to up-to-date techniques in the same way as any parastomal hernia. Because of the high recurrence rate after suture repair, the use of mesh in parastomal hernia repair is preferred [30].

Fistula Through the Nipple Valve

Key Concept: Internal fistulas are revised via laparotomy, and external fistulas are managed locally.

Fistulas may be external or internal bypassing the nipple valve (Fig. 10.9). The reported complication rate is about 25 % [17, 22], but reoperations may be successful [31]. The position of the fistula is mostly at the base of the nipple valve. Formerly silk sutures and/or synthetic material (Marlex or Mersilene ® mesh) used to stabilize the intussusception was a frequent underlying cause. As most authors have advised against the use of these products, the complication has now become rare. When a fistula appears today, suspicion of Crohn’s disease arises.

Fig. 10.9

Enterocutaneous fistula and fistula through nipple valve. (a) Enterocutaneous fistula. (b) Fistula through the nipple valve

While external fistulas should be best depicted by fistulography, internal fistulas are diagnosed by endoscopy. Repair of the external fistulas may be accomplished by local sutures after excision of its edges sometimes without a formal laparotomy. Internal fistulas through the nipple valve require laparotomy, however. Although desintussusception of the nipple valve and repair by excision of the fistula and reconstruction of the valve on the same intestinal segment may well be tried, such a repair is mostly unsuccessful. A more reliable option to deal with the problem is to resect the nipple valve with its outlet and to construct a new outlet as described for nipple valve sliding (Figs. 10.7 and 10.8). In cases with complicated fistula systems often turning out to be Crohn’s disease, pouch excision and construction of a conventional ileostomy is often the best solution.

Miscellaneous

Perforation of the reservoir a very rare complication which might be caused by too vigorous insertion of the catheter or by penetration of a sharp food object such as a fishbone. The closure of a perforation—particularly when associated with peritonitis—should be protected by a defunctioning loop ileostomy. Volvulus of the reservoir has been reported, but should not occur if the fixation of the reservoir is performed according to current principles. Fibrosis of the tip of the nipple valve is another complication that may require dilatation and occasionally reconstruction. Skin stricture around the stoma is also common but is easily dealt with by local revision.

Recurrent Nipple Valve Complications

Key Concept: Nipple valve dysfunction can be successfully revised, even after one or more previous revisions.

The policy in our institution has always been to recommend the patient to have revisional surgery to re-establish continence in cases of nipple dysfunction. Only occasionally would there be a need for removing the pouch due to any of these complications. An association between the number of revisions and conversion to conventional ileostomy has been suggested, but has so far not been confirmed [15, 32, 33].

It must in this context be emphasized that surgical revision of nipple dysfunction, although requiring another laparotomy, is in fact not necessarily a major undertaking. Even if such a reconstruction is again followed by sliding or any other defect of the nipple valve function, a further operation for restoration of continence is mostly justified and will be successful eventually [34]. It appears also from our experience—amounting to 40–50 years clinical practice—that once a patient has experienced the benefit of a continent ileostomy, such a patient usually insists on a further revision (even if it may be the third or fourth in order) and refuses to have the reservoir removed [35].

Ileitis (Pouchitis)

Key Concept: Similar to IPAA, continent ileostomies may develop pouchitis. Management is typically medical, though severe cases may require diversion or excision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree