Congenital gastrointestinal malformations

Iñaki Eizaguirre MD

Agustín Nogués MD

Introduction

The most significant congenital gastrointestinal malformations are Meckel’s diverticulum and anorectal malformations1, 2 (Table 14.1). The majority are developmental disturbances or embryopathies. These embryopathies occur in a phase in which all the organs are forming (3rd to 8th week), thus the presence of multiple anomalies is common. Other digestive tract malformations are foetopathies, probably due to ischaemic accidents that give rise to duodenal, intestinal, and colonic or rectal atresias. The interruption of the blood supply to a segment of the primitive intestine leads to the reabsorption of that segment, with the consequent atresia. This mechanism occurs later in the foetal period and is therefore not necessarily associated with other malformations3.

Table 14.1 Frequence of gastrointestinal malformations (number of cases/10,000 births) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Meckel’s diverticulum

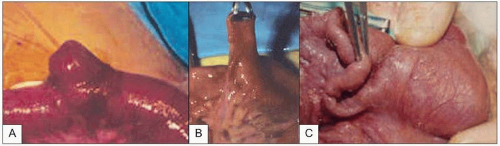

This is a formation in the shape of a cone or the finger of a glove attached to the anti-mesenteric margin of the ileum (14.1A, B). It can present in a variety of anatomical forms from the complete persistence of the yolk stalk, with the discharge of intestinal fluid through the umbilicus, to the presence of a fibrous cord that can give rise to intestinal obstruction by trapping a loop of bowel. There is also an infrequent giant form of Meckel’s diverticulum, which usually gives rise to episodes of occlusion in the neonate (14.1C).

Meckel’s diverticulum is found in 2% of autopsies, and is found in a 2:1 male/female ratio. It cause symptoms in only 4% of individuals; 50% have symptoms before 2 years of age and 80% before 10 years. Its histological structure is similar to that of the ileum. It can contain ectopic pancreatic tissue or gastric mucosa, explaining possible haemorrhage. Meckel’s diverticulum may present as haemorrhage (25-30%); it can invaginate and give rise to intestinal obstruction or as a diverticulitis with or without perforation.

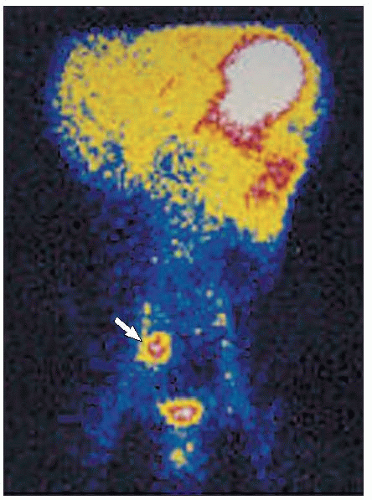

The most reliable diagnostic test is a 99mTc gamma scan (14.2). When the diverticulum contains ectopic gastric mucosa, this test shows an abnormal uptake in the centre of the abdomen. Treatment consists of resection of the diverticulum.

Anorectal malformations

Anorectal malformations are usually embryopathies, with associated abnormalities in 60% of cases: cardiovascular (tetralogy of Fallot); bone, particularly hemivertebrae; gastrointestinal: oesophageal atresia, duodenal atresia, Hirschsprung’s disease, or genitourinary: vesico-ureteric reflux. In 90% of cases there is an abnormal communication between the rectum and the urinary tract (in males) or the genital structures (in women). The description of the fistula gives an idea of the severity of the malformation: in males, rectoperineal, rectobulbar, rectoprostatic and rectovesical fistulae; in females, rectoperineal, rectovestibular, and rectovaginal fistulae and cloaca. All forms are considered severe with the exception of the rectoperineal forms, and require complex surgical treatment.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis uses perineal examination and ultrasound. It is worth waiting 24 hours for the rectal pouch to fill, facilitating evaluation of the malformation. A flat perineum is a poor prognostic indicator as it suggests an absence of musculature. Ultrasound is used to measure the distance from the rectal pouch to the skin. When this measures more than 1 cm, it is considered a severe form (14.3).

Treatment

In the milder forms (perineal fistula or <1 cm distance on ultrasound) treatment consists of performing a direct opening of the rectal sac (cut-back). In other cases, a colostomy and, in a second phase, descent via a posterior sagittal approach (Peña’s posterior sagittal anorectoplasty).

Oesophageal atresia

The abnormal separation of the tracheo-oesophageal bud gives rise to a large number of possible anatomical variations of this malformation, although the most frequent is type III (Table 14.2). Associated malformations are very common: bone 30%, heart defects 20%, urological 20%, digestive tract 20%, and VACTERL association: (Vertebral, Anal, Cardiac, Tracheal, oEsophageal, Renal, Limb).

Patients usually present with salivation, respiratory distress, and abdominal distension (forms with a distal fistula: III, IV, V).

Table 14.2 Different types of oesophageal atresia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

Prognosis and treatment

Survival varies from 97% in group I on the Spitz classification (weight >1500 g with no heart disease), to 47% in group II (weight <1500 g or heart disease) and 20% in group III (weight <1500 g and heart disease)2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree