Congenital Dilations of the Biliary Tract

Carlos U. Corvera

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

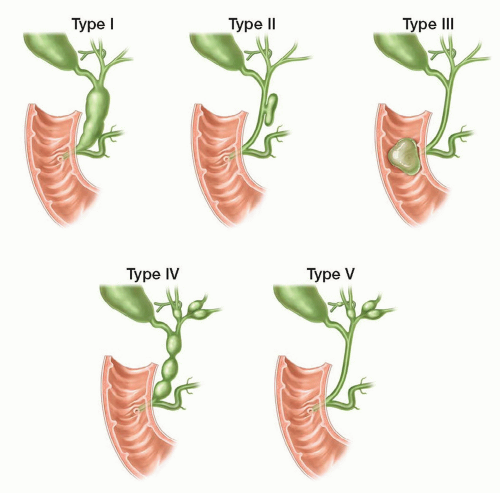

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSCholedochal cysts are abnormal dilations of the bile ducts, congenital in origin. Several classification systems have been proposed on the basis of the location, shape, or type of biliary dilation. The most widely adopted classification is Todani’s modification of the original Alonso-Lej description and encompasses five types of cysts (Fig. 29.1):

Type I—Fusiform or saccular dilation of the extrahepatic biliary tree involving both the common hepatic and common bile duct.

Type II—A supraduodenal diverticulum of the common hepatic or common bile duct.

Type III—Choledochoceles-intraduodenal diverticulum.

Type IV—Intrahepatic and extrahepatic fusiform cyst involvement.

Type V—Caroli’s disease-multiple intrahepatic cysts.

However, mounting evidence suggests that choledochoceles (Type III) and Caroli’s disease (Type V) are distinct clinical entities. This chapter will focus on the most common types of cysts, which represent fusiform dilations of the extrahepatic biliary tree involving both the common hepatic and common bile duct (Type I), with or without varying degrees of intrahepatic ductal involvement (Type IV). These congenital choledochal cysts are thought to be associated with yet another congenital anomaly involving the anatomy of the pancreatobiliary duct junction.

The clinical presentation of patients with choledochal cyst has changed from the classical “triad” of abdominal pain, jaundice and a right upper quadrant mass, probably as a result of modern advances in imaging technologies and widespread adoption of prenatal screening. Children are more likely to present with jaundice and/or a mass, whereas, choledochal cysts in adults may be identified incidentally or on evaluation of symptoms related to the long-term consequences/complications of the cyst, such as suppurative cholangitis, pancreatitis, cystolithiasis and/or malignancy. These welldescribed complications in adults have led to the evolution of surgical management from the historical simple drainage procedures to the current recommendation of complete cyst excision and biliary reconstruction.

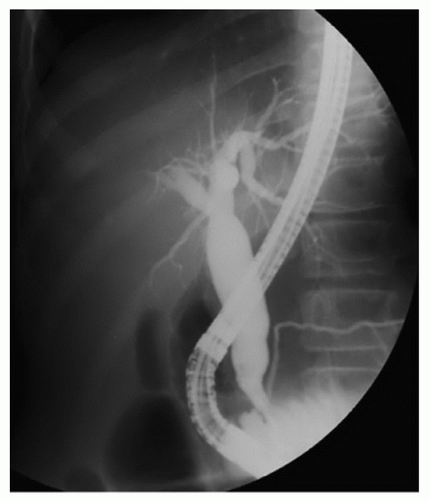

The diagnosis of choledochal cysts has been simplified by contemporary high resolution, three-dimensional, abdominal imaging technologies and widespread availability of interventional radiology and endoscopy. Imaging studies should clearly define the relationship of the cyst to the other portal structures. Abdominal ultrasonography is generally the first study obtained, followed by either computed tomography (CT), nuclear medicine: hydroxyimidoacetic acid scan (HIDA), or magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Fig. 29.2). If necessary, the diagnosis can be confirmed by more invasive studies such as percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Fig. 29.3). While these “direct” cholangiographic studies have the advantage of providing diagnostic information (i.e., cytologic brushings or biopsy), a disadvantage is that they can lead to serious periprocedural complications. PTC can be technically difficult to perform in patients with small nondilated duct require a more proximal approach, thereby increasing the risk of vascular injury. In these patients, acute pancreatitis can be precipitated more easily, probably because of the typical high insertion of the pancreatic duct into the biliary tract. Because of this, we recommend that these more invasive diagnostic studies be obtained only when the anatomy or the extent of the cyst requires further characterization.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING1. Clear delineation of biliary and ampullary anatomy by direct or indirect cholangiography is critical to avoid injury to the fragile narrow tapering of the distal bile duct (pancreaticobiliary junction). If the diagnosis is made during cholecystectomy, intraoperative cholangiography should be done to delineate the entire cyst anatomy. Otherwise, complete cross-sectional preoperative imaging by CT or MRI is necessary to define the extent of intrahepatic ductal involvement (see Chapter 18). If extensive unilateral hepatic involvement (usually the left side) is found, complete cyst excision with concomitant partial hepatectomy should be planned and discussed with the patient in the preoperative setting. Finally, the possibility of encountering malignancy should always be anticipated in the adult patient. Coexisting malignancy is suspected in patients who present with weight loss, jaundice, elevated tumor markers, and/or imaging findings that show a mass or intracystic mural nodules. Appropriate planning and counseling for additional surgical procedures, (i.e., concomitant hepatectomy, pancreatectomy, and/or need for extensive lymph node dissection) should be done preoperatively (see Chapter 26).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUECholedochal Cyst Resection—Pertinent Anatomy

A clear understanding of the anatomic relationships of the liver, biliary tract, portal vessels, and pancreas is essential for safe resection of congenital choledochal cysts (see Chapter 18). In addition, knowledge of common variations in the relationship of the right hepatic artery and cystic artery to the biliary tract is critical to avoid unexpected hemorrhage or biliary injury. The following are important anatomic relationships that must be understood to safely perform this procedure (Fig. 29.4):

The biliary confluence is typically situated anterior to the right branch of the main portal vein.

The right hepatic artery usually courses posterior to the common hepatic duct and gives rise to the cystic artery.

If present, a replaced or accessory right hepatic artery originates from the superior mesenteric artery and courses toward the liver, running posterolaterally along the right side of the common bile duct and behind the cystic duct before entering into Calot’s triangle.

The posterior location of the portal vein within the hepatoduodenal ligament is important to understand since it is typically distorted or displaced posteromedially by the enlarged fusiform biliary cyst.

Precise knowledge and identification of the portal vein is critical to avoid inadvertent injury during dissection, especially in cases associated with dense pericystic inflammation due to prior bouts of ascending cholangitis or pancreatitis.

The distal common bile duct courses downward and posteriorly to enter directly into the pancreas, or follows an extrapancreatic course for a short segment or within a posterior groove before it enters the substance of the gland.

Surgical Techniques for Congenital Dilations of the Biliary Tract

The surgical management of patients with congenital choledochal cysts continues to evolve. While traditional laparotomy via a midline, right transverse or subcostal incision remains popular, in the past decade, published reports of patients being treated by minimally invasive surgery (MIS) have surged worldwide. Most of these MIS experiences are laparoscopic, with a few case reports describing robot-assisted cyst excision and reconstruction. The application of MIS to treat congenital choledochal cysts is particularly attractive because the specimen is small and can be retrieved through a small port-site incision. Moreover, this disease generally affects young patients, in whom cosmetic concerns may be more important. Although the MIS approach requires further evaluation before it can be recommended as the new standard, the increasing utilization of minimally invasive surgical techniques in hepatobiliary diseases warrants description of this approach. Therefore, the traditional open and laparoscopic operative techniques for complete resection of choledochal cysts are described below.

Traditional Laparotomy “Open” Technique

Positioning

Patient is positioned supine with the right arm tucked and left arm out.

The choice of incision for exploration is based on surgeon’s preference and is influenced by patient size, body habitus, or presence of incision from prior laparotomy. We prefer a right-side, modified Makuuchi incision in patients with a steep costal margin and a standard right subcostal incision in patients with a wide abdominal surface and/or costal margin.

Complete Choledochal Cyst Excision

At exploration, the cyst should be immediately obvious bulging from the lateral edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament and distorting the first and second portion of the duodenum anteriorly.

Cholecystectomy is started by incising the peritoneum overlying the dilated and distorted gallbladder neck. The cystic duct typically arises from the lateral midportion of the fusiform cyst wall. The cystic artery is identified, isolated, clamped, divided, and ligated. A top-down dissection is used to mobilize the gallbladder from the liver bed.

A Kocher maneuver is done to mobilize the duodenum from the retroperitoneum.

The peritoneum is incised on the superior border along the first portion of the duodenum and it is reflected downward and rolled inferomedially to expose the anterior cyst wall. Since inflammation is minimal, this dissection is usually straightforward and is done in a blunt and sharp fashion until the distal bile duct/cyst is circumferentially isolated.

The lower end of the cyst is encircled with a vessel-loop or umbilical tape and used for traction. This maneuver provides excellent exposure of the adjacent portal vascular structures.

The fusiform dilation commonly extends behind the duodenum and into the substance of the pancreas. Therefore, as the dissection progresses inferiorly along the distal common bile duct, care must be taken not to injure the underlying pancreatic duct (Fig. 29.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree