Colorectal Manifestations of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV Infection)

Pranat Kumar

Lester Gottesman

In human affairs the best stimulus for running is to have something we must run from.

—ERIC HOFFER: The Ordeal of Change (1964)

▶ ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a Lentivirus, from the family of retroviruses, with an RNA genome. The disease was first recognized in the United States in 1981. HIV has since become the sixth leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated 40 million men, women, and children infected according to 2004 figures.290 In the United States, the number of new cases appears to be increasing.39 There were 41,113 new cases diagnosed in 2000.38 In 2006, that number jumped to 56,300 new cases.113 Improved medical therapy, with the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid-1990s, decreased the number of AIDS-related deaths, thus resulting in increased numbers of persons living with AIDS. In 2000, this number was estimated to be 337,731 in the United States.38 Whereas AIDS was initially confined to the homosexual population, intravenous drug users, and recipients of contaminated blood, there has been a noticeable increase in the incidence among the heterosexual population.

Mechanism of Viral Replication

HIV infects immune cells, thereby enabling replication of the virus. The HIV glycoprotein, gp120, interacts with the cell surface CD4 molecule and either the CXCR4 chemokine receptor (expressed in CD4+ T cells) or the CCR5 chemokine receptor (expressed in macrophages and primary T cells) to permit cellular entry of HIV. The viral RNA is reversetranscribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) by the enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT). The cDNA is then transported to the host cell nucleus and is integrated into the host cell DNA by the enzyme integrase, thereby permitting replication of the viral RNA and the synthesis of viral proteins. The enzyme, protease, sections the viral proteins into shorter pieces, which then encapsulate, allowing release of new virions.

Symptoms and Associated Conditions

HIV often causes a brief, flulike illness at the time of infection, but the virus may be harbored for many years without producing clinical manifestations. Because the acute infection generally produces mild, nonspecific symptoms, HIV infection is usually not diagnosed until several years after infection. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to various HIV proteins are detectable within 2 weeks of infection by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay and Western blot.156 IgG antibody is generally detected by 6 weeks after the onset of acute infection, although Imagawa and colleagues demonstrated that HIV infection may actually occur 35 months before detection of antibodies.126 However, this observation is generally thought to be the exception.

Acute HIV infection may manifest itself through fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, rash, weight loss, and fatigue.50 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and anorexia have also been reported during the acute illness.219,231 Immunologically, there is a precipitous drop in peripheral T-cell populations during the acute phase.55 This is transient and is followed by a lymphocytosis 3 to 4 weeks later, although there is a decrease in CD4+ cells relative to CD8+ cells.294

Progression of HIV results in a gradual decline of CD4+ cells and an increase in the number of virions (“viral load”). CD4+ lymphocyte counts are used as an indicator of disease progression. Individuals with CD4+ cell counts lower than 200 are considered to have advanced immunodeficiency, and, by definition, AIDS, and those with CD4+ cell counts lower than 50 have end-stage disease. HIV continually destroys resident T cells at a fairly constant rate and, after initial infection, stabilizes the rate of viral replication (called the set point) in each individual. This continues until the capacity of the immune system to restore itself is exhausted. Because T4 cells are constantly being replenished and destroyed, measurement of plasma HIV-1 RNA now appears to be a better prognostic indicator of disease activity than the CD4 count.85 Disease progression leads to increased opportunistic infections, AIDS-related malignancies, and, ultimately, death.

Colonic and anorectal problems in individuals who are HIV positive are mainly infectious in origin, as can be predicted from the immunodeficient status of the patients. Certain enteric infections have a high prevalence among homosexual men with and without AIDS, but especially if the latter condition supervenes. These include gonorrhea, syphilis, shigellosis, condylomata acuminata, campylobacteriosis, amebiasis, giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, cytomegalovirus infection, isosporiasis, candidiasis, and infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, Salmonella typhimurium, and Mycobacterium avium.197 Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage is an uncommon manifestation.36 Miles and colleagues noted that the most frequent reason for surgical referral was anorectal disease (5.9% of all HIV-positive patients), and warts comprised the single most common indication.170

Certain malignant tumors are seen more frequently in patients with AIDS. The most common are Kaposi’s sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), both of which may have colonic involvement. The incidence of anal squamous carcinoma is also increased in patients with AIDS.229

Intestinal and Anorectal Immunology and HIV

The mucosal layer on the surface of the gut provides a barrier to the large number of bacteria within the intestinal tract. Nonspecific mucosal defenses are extrinsic to the mucosa and form a protective barrier. These include the mucous coat; resident microflora, which prevent overgrowth of pathogenic organisms; proteolytic secretions; and glycocalyx. Secretory IgA, the primary immunoglobulin in external secretions, is the main immunologic defense in the gastrointestinal tract, and it acts as a non-complement-binding antibody that captures pathogens before they can invade the mucosal surface. An antigen that succeeds in penetrating this defense is processed by specialized epithelial cells on the mucosal surface, microvillus (M) cells, and is presented to immunologically competent cells in the lamina propria. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue is found in Peyer’s patches, solitary lymphoid follicles, and local, activated T cells within the lamina propria. Intraluminally, these lymphoid aggregates are covered with follicle-associated epithelium that contains M cells. M cells function to transport antigen to dendritic cells and tissue macrophages within the lymphoid aggregates, which, in turn, present antigen to CD4+ T cells and B cells.190 Once activated, resident T cells initiate cellular immunity by release of cytokines and modulation of other cellular immune elements, and B cells produce antigen-specific antibody.

HIV can gain access to lymphoid tissue within the lamina propria either through a break in the mucosa or by M cell-mediated transport. Within the lamina propria and epithelium of the intestinal tract, HIV infects resident T-cell and macrophage populations in the lymphoid aggregates and diffuses activated memory T cells. As described earlier, this is mediated through the cell surface coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue contains more than 50% of total lymphocytes in the body and as such represents an important HIV reservoir. It is unique in the proportion of activated memory T cells it contains, which is higher than in peripheral blood and lymph nodes. It has been postulated to be an early site of HIV infection and replication because the virus replicates more efficiently in activated memory T cells.224,262,295 In a primate model using simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), activated memory CD4 T cells were found to be rapidly depleted within days of SIV infection. The early, selective, rapid infection and depletion of intestinal lymphoid tissue led the authors to hypothesize that acute HIV and SIV infection is primarily a disease of the mucosal/intestinal immune system.262 The early infection and apoptosis of intestinal mucosal CD4 T cells may explain the abdominal complaints common in early HIV infection described earlier. The depletion of CD4 T cells adversely affects immunoglobulin production and mucosal integrity, thereby promoting translocation of bacteria and subsequent bacterial invasion.96 A similar phenomenon has been more recently described for vaginal mucosal CD4 T cells, which likewise serves as an early site of entry and replication of HIV.263

The squamous epithelium of the anal canal and anal verge also has immunologic function. Both CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes and dendritic cells, which function as antigenpresenting cells, are present in the anal mucosa.30,97 Dendritic cells, also known as Langerhans cells after migration

to the epithelium, act as antigen-presenting cells to activate a cellular immune response.254 In their capacity as antigenpresenting cells, epithelial and subepithelial dendritic cells of the anal canal may act to facilitate access of HIV to the mucosal lymphoid system. The capacity to migrate from initial points of entry, together with their capacity to activate the cellular immune response by recruiting and activating large numbers of T cells, led some researchers to propose that these cells play an integral role in sexual transmission of HIV.144

to the epithelium, act as antigen-presenting cells to activate a cellular immune response.254 In their capacity as antigenpresenting cells, epithelial and subepithelial dendritic cells of the anal canal may act to facilitate access of HIV to the mucosal lymphoid system. The capacity to migrate from initial points of entry, together with their capacity to activate the cellular immune response by recruiting and activating large numbers of T cells, led some researchers to propose that these cells play an integral role in sexual transmission of HIV.144

The interaction of HIV, anal canal dendritic cells, and mucosal T cells may explain the effect of HIV on other viral infections of the anal canal in HIV-positive patients, including human papillomavirus (HPV). Persistent HPV infection in HIV-positive patients may be secondary to local immune dysfunction rather than to generalized immunosuppression.61 Sobhani and coworkers have shown a decrease in the number of dendritic cells in the anal mucosa of HIV-positive patients with HPV infection compared with HIV-negative controls,243 a finding that may explain the more aggressive nature of HPV infection in HIV-positive patients.

New antiviral therapies and mucosal vaccines are being investigated that would block the transmission of HIV to T cells by dendritic cells via the membrane protein, DC-SIGN, which binds the HIV-1 envelope.198

Antiretroviral Therapy

HAART has profoundly affected the progression of HIV disease. HAART reduces plasma viral load, increases CD4 T-cell counts, and reduces the incidence of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients.83,189 HAART is a combination of three or more antiretroviral drugs from two or, sometimes, three different classes of drugs. Class-sparing regimens have been advocated to allow for second-line therapy in case of resistance.1 The three classes of drugs used in HAART are the nucleoside RT inhibitors (NRTIs), the nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs), and the protease inhibitors (PIs). More recently, a fourth class, the fusion inhibitors, has been introduced and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The NRTIs were the first class of antiretroviral drugs, introduced with zidovudine (formerly known as azidothymidine or AZT).114 The NRTIs are dideoxynucleoside analogues that, once phosphorylated, can be incorporated into the cDNA, causing early chain termination and preventing HIV replication. The NNRTIs, like the NRTIs, prevent the transcription of the HIV RNA into cDNA. However, unlike the NRTIs, the NNRTIs do not act as substrates for the enzyme but rather bind to the active site of the enzyme, preventing viral DNA synthesis. PIs, introduced in 1995, inhibit the enzyme HIV protease, blocking the final cleavage of HIV proteins and preventing the assembly of new virions.69 Combination antiviral therapy with a PI is more effective in reducing plasma HIV-1 RNA compared with regimens without a PI.111 In March 2003, the FDA approved enfuvirtide (Fuzeon), the first fusion inhibitor to be approved for use in combination with other antiretroviral drugs. The fusion inhibitors, a novel class of drug, differ from previous HIV medications in that they do not disrupt the replication and release of HIV but rather prevent the entry of HIV into the target cell.130 Unlike other antiretrovirals, enfuvirtide lacks oral availability and is administered by subcutaneous injection twice daily. However, this class of drugs has had limited clinical use because of rapid induction of resistance.118

The impact of HAART on the intestinal mucosal immune system has not been shown to be as effective as it is in the peripheral immune system.256 As mentioned earlier, the gutassociated lymphoid tissue represents a large reservoir for HIV infection and is affected by HIV early in the course of infection with a dramatic loss of lymphoid cells and, by extension, decrease in the immune function of the intestinal mucosa. Talal and coworkers examined the effects of HAART on gut-associated lymphoid tissue in a small, prospective study with eight patients. In all individuals, levels of HIV-1 RNA fell to less than detectable levels after 6 months of therapy in both gut-associated lymphoid tissue and plasma. Immune reconstitution, however, was less dramatic in intestinal lymphoid tissue compared with peripheral blood.253 Other authors have documented a similar decrease in HIV-1 RNA but with a significant increase in CD4 T-cell counts in rectal biopsies.149

Although HAART has not yet been definitively shown to result in immune reconstitution of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, combination antiviral therapy has had a tremendous impact on intestinal manifestations of HIV. The incidence of AIDS-associated intestinal malignancies and opportunistic infections has decreased since the advent of HAART. The prevalence of opportunistic pathogens in endoscopic biopsy specimens in HIV-infected patients decreased from 69% to 13% following the introduction of HAART.173 Similarly, the incidence of opportunistic infections causing chronic diarrhea in patients with AIDS decreased from 53% to 13% following the introduction of HAART.30 However, the overall incidence of diarrhea remains high, a concern that may be secondary to PIs. Diarrhea is a common side effect of these inhibitors and is noted in up to 70% of patients. Treatment for opportunistic pathogens in HIV-infected patients with chronic diarrhea is more successful in patients receiving HAART. In a study of 282 individuals, those receiving PIs had a significantly higher response rate to the treatment for pathogen-identified diarrhea.18 Immune reconstitution of gutassociated lymphoid tissue with an increase in CD4 T cells and recovery from cryptosporidiosis in an HIV-infected patient following initiation of HAART have been described.221

Surgery and Surgical Outcome

Surgical consultation is often sought in patients with HIV infection or AIDS for complaints of abdominal pain. Many of the opportunistic gastrointestinal diseases that are seen in patients with AIDS may present with severe abdominal pain that can mimic standard surgical conditions. The majority of these can safely be managed nonoperatively. Generally, the goal in management of the acute abdomen in a patient with HIV is to try to avoid surgery.84,228 Evaluating by means of computed tomography and endoscopy, understanding the natural history of the colonic manifestations, and knowing the expected responses from pharmacologic intervention will usually allow the surgeon to avoid an unnecessary and unhelpful laparotomy. However, intestinal perforation, gastrointestinal bleeding, and obstruction as a consequence of infection or malignancy may be seen in HIV-positive patients, and these manifestations often necessitate surgical intervention.

Numerous articles have been published on the results of surgery in individuals who harbor the AIDS virus and in those who have the full-blown picture of AIDS or AIDS-related complex.66,107,225,282 Wolkomir and colleagues reported

474 patients who underwent abdominal and anorectal surgery with these conditions.288 None required surgery for complications secondary to cytomegalovirus, visceral lymphoma, or visceral Kaposi’s sarcoma. Although no deaths occurred within 30 days, the morbidity rate was 72%. The rate of wound healing was inversely related to the white blood cell count. Deneve and coworkers reported their single institution experience in 77 patients with a preoperative diagnosis of HIV or AIDS.70 They found that a lower CD4 count was associated with a higher likelihood of urgent operation, increased overall complication rate, and higher mortality. Wilson and colleagues submitted their experience of 36 major abdominal operations performed on 35 patients with AIDS.287 Cytomegalovirus was the most common pathogen. Mycobacterial infections presented as retroperitoneal adenopathy or splenic abscess, and NHL was the most common malignancy identified.112 Elective mortality was 9% at 30 days and 46% when an emergency operation was necessary. In a study by Chambers and Lord, the outcome of laparotomy in patients with AIDS who were found to have AIDS-related pathology was compared with those with non-AIDS-related pathology.41 Those in the former group were found at the time of laparotomy to have lower mean body weights, serum albumin levels, and CD4 T-cell counts. The most frequent postoperative AIDS-related pathology was B-cell NHL. The 30-day mortality rate was 17%, and the complication rate was 70%, with no significant difference between patients with AIDS or with AIDS-related pathology and those with non-AIDS-related pathology. More than 50% of postoperative complications were infectious in origin (pulmonary, wound, and systemic sepsis). This is in contrast to an earlier study in which a slightly higher mortality rate in patients with AIDS-related pathology at laparotomy was observed (47%) compared with patients with non-AIDS-related pathology.20 Postoperative complications have been noted to occur with a higher frequency (61% vs. 7%) in patients with AIDS than in asymptomatic HIV-infected patients. Again, most complications were infectious in origin.290

474 patients who underwent abdominal and anorectal surgery with these conditions.288 None required surgery for complications secondary to cytomegalovirus, visceral lymphoma, or visceral Kaposi’s sarcoma. Although no deaths occurred within 30 days, the morbidity rate was 72%. The rate of wound healing was inversely related to the white blood cell count. Deneve and coworkers reported their single institution experience in 77 patients with a preoperative diagnosis of HIV or AIDS.70 They found that a lower CD4 count was associated with a higher likelihood of urgent operation, increased overall complication rate, and higher mortality. Wilson and colleagues submitted their experience of 36 major abdominal operations performed on 35 patients with AIDS.287 Cytomegalovirus was the most common pathogen. Mycobacterial infections presented as retroperitoneal adenopathy or splenic abscess, and NHL was the most common malignancy identified.112 Elective mortality was 9% at 30 days and 46% when an emergency operation was necessary. In a study by Chambers and Lord, the outcome of laparotomy in patients with AIDS who were found to have AIDS-related pathology was compared with those with non-AIDS-related pathology.41 Those in the former group were found at the time of laparotomy to have lower mean body weights, serum albumin levels, and CD4 T-cell counts. The most frequent postoperative AIDS-related pathology was B-cell NHL. The 30-day mortality rate was 17%, and the complication rate was 70%, with no significant difference between patients with AIDS or with AIDS-related pathology and those with non-AIDS-related pathology. More than 50% of postoperative complications were infectious in origin (pulmonary, wound, and systemic sepsis). This is in contrast to an earlier study in which a slightly higher mortality rate in patients with AIDS-related pathology at laparotomy was observed (47%) compared with patients with non-AIDS-related pathology.20 Postoperative complications have been noted to occur with a higher frequency (61% vs. 7%) in patients with AIDS than in asymptomatic HIV-infected patients. Again, most complications were infectious in origin.290

With the addition of highly active antiretroviral therapies, there has been a significant reduction in abdominal complications associated with opportunistic infections.204 Monkemuller and associates reported a decrease in opportunistic infections from 69% in the pre-HAART era to 13% currently.173 Antiretroviral therapy has also been associated with a reduction in operative mortality when compared to outcomes in the pre-HAART era. Mortality rates ranged from 57% to 86% in HIV/AIDS patients before the advent of HAART.210,216,281 Recent studies have shown that operative mortality is as low as 11% to 19% for emergency abdominal surgery in patients on HAART.66,257,291

In contrast to intra-abdominal surgical procedures, perianal surgical procedures do not appear to carry a higher morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients.34 Barrett and coworkers reported a 2% complication rate in 485 anorectal procedures, and there were no deaths.10 This is consistent with our own experience.

However, surgeons must not forget that illnesses common in non-HIV patients may also occur in the immunocompromised HIV patient. In fact, conditions such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, peptic ulcer disease, ischemic bowel disease, and symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm have been reported to occur with the same frequency in HIV and in non-HIV patient groups.210,239,293

Postoperative Complications and Wound Healing

Early reports about poor wound healing and fear of becoming infected through inadvertent exposure have contributed to the reluctance of many surgeons to operate on HIV-positive patients. Analysis of data suggests an inverse relationship between CD4 T-cell count and wound healing—that is, poor wound healing is associated with low CD4 T-cell counts in lesions not expected to heal, such as malignancies and ulcers.53 More recently, a greater incidence of wound complications in HIV-positive patients has been reported.68 CD4 T-cell counts do appear to be a prognostic factor in surgical outcome in patients with AIDS. Albaran and coworkers found that patients with CD4 T-cell counts lower than 200 cells/mm3 had increased morbidity and mortality rates following surgery.2 An increased incidence of surgical infection, regardless of the type of operative procedure, has been noted in HIV-positive patients with CD4 T-cell counts lower than 200 cells/mm3.81 In experimental studies, abdominal wounds in thymectomized rats with depletion of CD4 lymphocytes have been found to have a significant decrease in strength, resilience, and toughness.67 The effect of viral load on postoperative outcomes has also been studied. In their retrospective study, Horberg and colleagues found that a viral load equal to or greater than 30,000 copies per milliliter was associated with increased postsurgical complications.124

Similar results of lower CD4 T-cell counts on wound healing and outcome following anorectal surgery have been reported. Viral load has also been studied as a prognostic indicator following surgery in HIV-positive patients,281 although as noted earlier, more recent studies found no increased incidence of complications following anorectal surgery. Studies have demonstrated that viral load is the best single predictor of clinical outcome, followed by CD4 T-cell counts.19,165 Unfortunately, no studies have examined the prognostic value of the extent of viremia on postoperative outcome.

Given the evidence available, increased wound and other infective complications should be expected following abdominal and, possibly, anorectal surgery.128 The prognostic values of CD4 T-cell counts and viral load indicates that optimization of the patient with immune reconstitution through HAART should be beneficial before semielective and elective procedures. Obviously, this is not possible in the emergency situation.

▶ COLONIC MANIFESTATIONS OF HIV INFECTION

Gastrointestinal disease is seen frequently in HIV-infected patients. Specifically, a variety of disease processes may affect the colon in an individual who harbors HIV. These may present in a number of ways. Diarrhea has been reported to affect up to 50% of patients with AIDS in North America and is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among such persons.241 Chronic diarrhea is seen more frequently in male homosexual HIV-infected patients and in those with severely depleted CD4 T-cell counts.135,206 Gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation are most commonly seen in enteroinvasive infections, such as those caused by cytomegalovirus and Clostridium difficile, but they may be secondary to gastrointestinal involvement by HIV-associated malignancies. Obstruction

may be seen with malignant disease, primarily Kaposi’s sarcoma and NHLs. Finally, lymphadenopathy itself may cause severe abdominal pain and compression of viscera, primarily through a M. avium complex (MAC) infection.

may be seen with malignant disease, primarily Kaposi’s sarcoma and NHLs. Finally, lymphadenopathy itself may cause severe abdominal pain and compression of viscera, primarily through a M. avium complex (MAC) infection.

Diarrheal Conditions

Diarrhea is seen in approximately 50% of patients with AIDS.241 Chronic diarrhea results in a decreased quality of life and contributes to the morbidity of HIV infection. The etiology is multifactorial. Certainly, the ability to identify an organism depends on how vigorously the cause is pursued.23 Infection with HIV is thought to cause minor alterations in architecture of the villi, which may lead to mild malabsorption of carbohydrates;136 this can cause diarrhea also. Furthermore, increased permeability resulting from cytokine activation by foreign antigens, as well as bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel, may also contribute to pathogennegative diarrhea.13 HIV has amino acid sequences similar to those of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and may induce diarrhea by upregulation of VIP receptors.264 HIV infection of the intestinal tract may also affect the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium. Stockmann and coworkers have proposed a leak-flux mechanism for diarrhea in HIV-infected individuals, secondary to intestinal mucosal cytokine release with resultant disruption of the epithelial barrier.250

Patients who present with diarrhea and abdominal pain should be assessed with a detailed history and physical examination, routine laboratory studies, and stool studies. The patient’s immune status should be assessed by CD4 T-cell count and viral load. Recent exposure history can be obtained by careful attention to sexual history, travel, diet (to rule out food intolerance), and medications (specifically, PIs and antibiotic use). The characteristics of the diarrhea should be assessed, including duration, severity, associated abdominal pain, hematochezia, weight loss, and fever. Frequent, small movements with associated tenesmus are more indicative of an anorectal cause, whereas bloody movements and fever suggest an enteroinvasive, colonic pathogen. Physical examination should include a careful abdominal examination with attention to organomegaly, tenderness, and distension; an anorectal examination to assess for perianal lesions that may highlight an infectious source (e.g., herpes simplex); and a general physical evaluation to determine temperature, the presence or absence of cachexia, and lymphadenopathy.175

The American Gastroenterological Society created guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic diarrhea in HIV-infected patients.285 Recommendations include stool samples for bacteria and parasites, as well as for C. difficile if there is a risk for antibiotic-associated diarrhea. In the febrile patient, blood cultures should be drawn for bacteria and, in severely immunocompromised patients with CD4 T-cell counts lower than 100 cells/mm3, for mycobacteria. For those in whom stool studies fail to identify an infectious cause, endoscopy and mucosal biopsy are recommended, particularly in patients whose symptoms indicate a rectal or colonic cause. Flexible sigmoidoscopy with mucosal biopsies for microscopic examination and for bacterial and mycobacterial culture should be performed. Total colonoscopy may be necessary in certain patients, particularly when cytomegalovirus infection is suspected, given the high incidence of isolated proximal colonic involvement. Finally, esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed with duodenal biopsies when other investigations have failed to reveal a source. This may aid in identifying Giardia, MAC, microsporidia, or Isospora. With a comprehensive investigation, an etiologic agent can be found in 90% of patients.23 Among identified causes of diarrhea in patients with AIDS and chronic diarrhea, the most common opportunistic pathogens are cytomegalovirus, MAC, and the protozoans Cryptosporidia and Microsporidia.285 Treatment of pathogen-negative diarrhea consists of rehydration and somatostatin analogues.237

Cytomegalovirus Infection

Cytomegalovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus from the herpesvirus family. It was first isolated in 1956 and has been found in urine, feces, semen, saliva, breast milk, blood, and cervical and vaginal secretions.207 Although ubiquitous in humans, cytomegalovirus does not produce symptoms; it becomes an opportunistic infection as immune function deteriorates. Infection with cytomegalovirus is extremely common in patients with AIDS.176 Disseminated cytomegalovirus has been identified in 90% of patients with AIDS at autopsy, with 94% of homosexual men testing positive at some venereal disease clinics.282 Colonic cytomegalovirus is a common cause of diarrhea and abdominal pain in patients with AIDS, with resultant morbidity and mortality.285

Gastrointestinal manifestations of cytomegalovirus infection include ulcers, which may occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract, enteritis, colitis, ileocecal obstruction, perforation, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The colon is the main target in the gastrointestinal tract, and ileocolitis is the major colorectal manifestation.75,205,277 In a study examining the colonoscopic findings of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with AIDS, ulcerations, colitis, and subendothelial hemorrhage were the most common findings. Disease limited to the right colon was seen in 13% of patients, again emphasizing the need for complete colonoscopy in those with suspected cytomegalovirus.284 The diagnosis of cytomegalovirus colitis should always be considered in patients with AIDS who develop an acute abdomen, especially if a free perforation is diagnosed on radiographic study (see later).

Symptoms and Findings

The most common manifestation of colonic cytomegalovirus infection is watery diarrhea.72,73,167 Bloody stools are common and may be seen in the absence of diarrhea. Abdominal pain may be severe, mimicking an acute surgical abdomen.284 Up to 30% of patients may complain of fever and weight loss without diarrhea.72 As the virally induced vasculitis progresses, thrombosis, occlusion, and ischemia of the affected area may occur. Toxic megacolon, hemorrhage, and perforation have been reported; this is of obvious interest to the surgeon.101,271,282 Cytomegalovirus enterocolitis was the single most common reason for abdominal surgery in the AIDS population in the experience of Wilson and colleagues and is the most frequent life-threatening condition requiring emergency celiotomy in these individuals.151,287 However, effective antiviral therapy has reduced the incidence of these severe complications.271

Diagnosis

The accurate diagnosis of cytomegalovirus colitis is sometimes quite difficult. Endoscopically, the mucosa in cytomegalovirus colitis is diffusely erythematous and friable with ulcerations. The ulcers themselves range from shallow, punctate lesions

to deeply coalescing ulcers, the appearance of which may be difficult to distinguish from that of other colitides. Submucosal hemorrhage, secondary to cytomegalovirus-induced vasculitis, may be seen. Colonic involvement is patchy or limited to one region. As mentioned, patchy colitis localized to the right colon may be seen in 13% to 40% of patients, necessitating full colonoscopy rather than sigmoidoscopy.72,151,284 However, in 25% of those with cytomegalovirus colitis, the mucosa appears endoscopically normal. For diagnosis, biopsy samples are taken randomly from the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. Cytomegalovirus may be demonstrated on histologic examination of grossly normal mucosa; therefore, samples of both inflamed and noninflamed areas should be taken.

to deeply coalescing ulcers, the appearance of which may be difficult to distinguish from that of other colitides. Submucosal hemorrhage, secondary to cytomegalovirus-induced vasculitis, may be seen. Colonic involvement is patchy or limited to one region. As mentioned, patchy colitis localized to the right colon may be seen in 13% to 40% of patients, necessitating full colonoscopy rather than sigmoidoscopy.72,151,284 However, in 25% of those with cytomegalovirus colitis, the mucosa appears endoscopically normal. For diagnosis, biopsy samples are taken randomly from the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. Cytomegalovirus may be demonstrated on histologic examination of grossly normal mucosa; therefore, samples of both inflamed and noninflamed areas should be taken.

Pathology

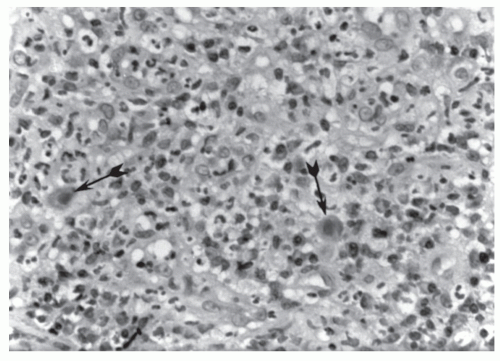

Biopsy usually reveals an inflammatory infiltrate, including lymphocytes and plasma cells with, in some areas, polymorphonuclear leukocytes and histiocytes.74,209 Cellular changes seen under light microscopy are colonic mucosal cell enlargement with basophilic intranuclear inclusions, surrounded by a clear halo that gives the characteristic “owl’s eye” appearance (Figure 10-1).121 The retrieval of cytomegalovirus inclusions appears to depend on the number of biopsy specimens, the skill of the pathologist, and whether the material was taken from an endoscopically abnormal colon.103,167 Cultures for cytomegalovirus have been inconsistent in predicting the presence of active infection. In situ hybridization staining and polymerase chain reaction may increase the sensitivity of histologic analysis.59,227 Polymerase chain reaction amplification of cytomegalovirus DNA offers the best method for both diagnosis and monitoring of the efficacy of therapy.58

Radiologic investigation, specifically computed tomography, usually reveals the nonspecific changes of colitis, with colonic thickening and diffuse ulcerations.

Management

Medical management includes the antiviral agents ganciclovir, valganciclovir, and foscarnet. Ganciclovir is given intravenously at a dose of 5 mg/kg twice a day, and valganciclovir is given as a single 900-mg dose orally. Ganciclovir is the treatment of choice for induction of gastrointestinal disease, and recent reports show that valganciclovir may be as effective for mild disease. However, valganciclovir is not recommended in severe disease where absorption may be compromised.9 Ganciclovir usually improves both the histologic and macroscopic appearance within 3 weeks. If there is no improvement, foscarnet, at a dose of 60 to 90 mg/kg intravenously three times daily, should be used. Complete response to ganciclovir and/or foscarnet therapy can be expected in approximately 90%. However, because relapse is very common (50%), maintenance therapy should always be considered.19,63 Patients receiving such treatment and those taking PIs have been demonstrated to have the lowest recurrence rates and an improved survival.19

FIGURE 10-1. Cytomegalovirus enterocolitis. Acutely inflamed granulation tissue with cells positive for cytomegalovirus demonstrating intranuclear inclusions (arrows). (Original magnification × 400.) |

Surgical intervention is reserved for perforation, massive bleeding, and toxic megacolon. However, a patient with mild peritoneal signs, without free air, and with the presumptive diagnosis of cytomegalovirus colitis may be treated with both ganciclovir and appropriate antibiotics for aerobic and anaerobic organisms while he or she is observed carefully. Most individuals will respond without the need for surgical intervention. However, when emergency surgery is required, resection of the involved segment of colon is necessary. No anastomosis should be performed under these circumstances.

Results of Surgery

Approximately two-thirds of patients with AIDS who underwent emergency bowel resection by Wexner and colleagues had cytomegalovirus ileocolitis.282 The postoperative mortality was 28% at 1 day, 71% at 1 month, and 86% at 6 months. Death often is a consequence of sepsis and pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci.151 Elective resection of eight patients reported by Söderlund and coworkers resulted in one death.245 Recurrent or persistent symptoms of cytomegalovirus enterocolitis occurred in four patients after a mean of 7 months.

Mycobacterium Avium Complex Infection

MAC affects about 5% of severely immunocompromised HIV patients and is diagnosed in 50% of those with AIDS.76 This is an environmental bacterium that enters through both the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts.16 Typically, patients with gastrointestinal MAC infection have low CD4 T-cell counts. In addition to severe diarrhea, patients may report abdominal pain, anorexia, and weight loss. Anemia may be identified upon laboratory evaluation. Abdominal pain may be secondary to intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy. This is readily diagnosed by computed tomography and needle aspiration.5 Colonic infection may result in obstruction, fistula formation, and perforation, although these are uncommon, and surgery is rarely indicated in the management of gastrointestinal MAC.111

Diagnosis is made on biopsy of either affected small intestine or colon. The endoscopic appearance of MAC is quite distinctive, with granular, small (4-mm) white nodules with surrounding erythema. Colonic mucosa may be edematous and, uncommonly, ulcerated. Biopsy cultures are used to confirm the diagnosis and permit sensitivity typing. Because MAC is a systemic disease, blood cultures may be taken to confirm the diagnosis and have been reported to be more helpful than either stool or respiratory specimens for establishing the diagnosis with certainty.46

Medical treatment of gastrointestinal MAC is with a combination of antituberculous drugs. Ethambutol (15 to 25 mg/kg daily), ciprofloxacin (500 to 750 mg twice daily), rifampin (600 mg daily), rifabutin (450 to 600 mg daily), amikacin (10 to 15 mg/kg daily), clofazimine (50 to 200 mg daily), and azithromycin (500 mg daily) may be used in three or four drug regimens for a 12-week treatment period.14,32 Response to quadruple therapy is good, with more than onehalf of patients demonstrating complete response and resolution of symptoms.138

Protozoal Infections

Microsporidia Infection

Microsporidia, of which Enterocytozoon bieneusi accounts for the majority of cases in patients with AIDS, are obligate intracellular, spore-forming protozoa. Microsporidia have been identified in up to 60% of patients with AIDS with chronic diarrhea.172,244 Microsporidiosis is usually seen in those with advanced AIDS with CD4 T-cell counts lower than 100 cells/mm3. Patients present with frequent, watery bowel movements (nonbloody), abdominal pain, and nausea.

Diagnosis. Microsporidiosis most frequently affects the proximal jejunum. Upper endoscopy with a pediatric colonoscope is necessary to obtain biopsies. Histologically, characteristic small, round/oval plasmodia and spores within the infected enterocyte cytoplasm, typically supranuclear in the apical cytoplasm, are demonstrated.181 Atrophy of intestinal villi and crypt hyperplasia are seen microscopically, and the resultant changes in absorption contribute to the diarrhea.195

Colonoscopy with terminal ileal biopsies may permit visualization of the organisms and should be performed when microsporidiosis is suspected. Although examination of biopsy specimens is the most sensitive method for detection, microscopic examination of stool samples, both with trichrome staining and indirect immunofluorescence, using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies, may diagnose the condition.273,296

Treatment. Treatment of microsporidiosis is difficult and generally does not result in eradication of the infection. The destruction of the resident T cells in the lamina propria of the gut is probably responsible for the persistence of these protozoal infections.158 Albendazole, 400 mg twice daily, is the recommended drug. Clinically, a partial response of more than 50% reduction in bowel movements was noted in one study, although repeat endoscopy revealed persistence of infection in all regardless of clinical response.71 More recently, thalidomide has been investigated as a drug to treat the condition. Thalidomide, 100 mg daily for 30 days, was found to result in a complete clinical response in 7 of 28 patients.232 Immune reconstitution with HAART has been noted to result in a complete clinical response in patients with microsporidiosis and cryptosporidiosis.33

Cryptosporidium Infection

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite that primarily affects the small intestine and causes a profuse, watery diarrhea (see Chapter 33). Cryptosporidium oocysts are spread by person-to-person contact and by contaminated water transmission. It is a common source of diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals worldwide but is usually self-limiting in the nonimmunocompromised host. In HIV-positive patients, cryptosporidiosis is self-limited in up to one-third of patients with CD4 T-cell counts higher than 200/μL. However, in patients with AIDS with lower CD4 T-cell counts, Cryptosporidium may result in a serious, chronic disease with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia, in addition to diarrhea.87 Infection can be fatal, with severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, and wasting.

Diagnosis. Cryptosporidium affects primarily the jejunum and ileum, resulting in villous atrophy, malabsorption, and altered permeability.104 Cryptosporidium may produce an enterotoxin that results in hypersecretion of fluid into the bowel and the large-volume diarrhea seen clinically.110 Diagnosis is made by stool examination with modified acid-fast stain and light microscopy to detect oocysts (see Figure 33-31). Alternatively, immunofluorescence antibody may be used with increased sensitivity.95 Endoscopic biopsy demonstrates the intracellular protozoa, villous atrophy, and inflammation of the lamina propria.

Treatment. Treatment of cryptosporidiosis is difficult, and there still remains no ideal regimen. As noted earlier, immune reconstitution with HAART may result in resolution of symptoms. A more recent study demonstrated that a combination of azithromycin and paromomycin may be promising, with almost complete eradication of oocyst excretion at 12 weeks.240 Preventive measures include avoiding drinking water directly from lakes and waters, careful hand washing after contact with human and animal feces, and avoidance of oral-anal sexual practices.

Clostridium Difficile Infection (See also Chapter 33)

C. difficile colitis is the most common cause of bacterial diarrhea in HIV patients.217 It is common among AIDS victims because many who are infected with HIV receive a variety of antimicrobial agents, either for prophylaxis or for treatment of bacterial illnesses. In addition, repeat hospital admissions predispose the patient to colonization with the organism.

The observed frequency of C. difficile-associated diarrhea among patients with AIDS has actually decreased in the era of HAART. It has been postulated that this is secondary to the reduced number of hospital visits in patients with restored immunity on antiretroviral therapy.217

The observed frequency of C. difficile-associated diarrhea among patients with AIDS has actually decreased in the era of HAART. It has been postulated that this is secondary to the reduced number of hospital visits in patients with restored immunity on antiretroviral therapy.217

The typical presentation includes mucoid diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever (see Chapter 33). The condition may progress to that of acute megacolon as well as to lifethreatening diarrhea.137

Diagnosis is made by testing stool for toxin A or toxin B, both of which are produced by C. difficile. Endoscopy is usually not indicated and, in fact, should be discouraged in patients with severe disease without suspicion of necrosis. Endoscopically, the colonic mucosa appears inflamed. Ulcerations and pseudomembranes may be present. However, in the patient with AIDS, the colitis may lack characteristic pseudomembranes and may also involve a secondary pathogen, such as cytomegalovirus.35

Treatment is with either oral vancomycin (125 mg, four times daily) or metronidazole (250 mg, four times daily). In severe disease, a combination of intravenous metronidazole (Flagyl) and oral vancomycin is recommended. With profuse diarrhea, oral cholestyramine may be used to bind toxin and to reduce stool frequency. Fidaxomicin, a potential new agent in the treatment of C. difficile, is a macrolide antibiotic that has recently been shown in a clinical trial to be as effective as vancomycin in treating infection with this organism and may be superior for preventing recurrence.160 Current investigations of fecal transplant to reconstitute the flora of the colon are also underway. The reader is referred to Chapter 33 for a comprehensive discussion of antibioticassociated colitis.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasma capsulatum is a fungus that usually causes subclinical infection when its airborne spore is inhaled.108 The risk of developing histoplasmosis and the severity of disease are dependent on the immune status of HIV-infected individuals. Disseminated histoplasmosis is usually seen in patients with CD4 T-cell counts lower than 200 cells/mm3.283 Gastrointestinal involvement is common in disseminated histoplasmosis, although symptomatic gastrointestinal disease is only seen in a small percentage of patients.

Symptoms of gastrointestinal histoplasmosis are nonspecific and include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, and weight loss. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis may also present with gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction, or perforation.89,119,139,248 Dissemination of the fungus may cause focal lesions affecting any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. However, the terminal ileum and ascending colon are the most frequently involved sites, probably because of the presence of considerable lymphoid tissue.11 The lesions may appear as polyps or may coalesce to form inflammatory masses that may mimic carcinoma.8 An additional discussion concerning this fungal infection is found in Chapter 33.

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

NHL is an AIDS-defining malignancy. HIV infection increases the risk of systemic NHL by 200-fold, with the greatest increase in high-grade NHL.57 Extranodal NHL occurs in approximately 10% of HIV-infected individuals, and it had become the most common malignant disease associated with AIDS in certain areas until the mid-1990s.109 However, after a steady increase in the number of NHL cases up until 1995, there has since been a decline.65 Unlike Kaposi’s sarcoma (see later), there is little variation in the incidence of NHL between different HIV exposure groups. It tends to occur in advanced disease in those individuals with a CD4 cell count of less than 50/mm3.202

Pathogenesis

The biology and presentation of NHL in HIV-positive individuals are different from those of the general population in that high-grade lymphomas are more frequent with HIV infection. The biology of these lymphomas varies in relationship to morphologic type, anatomic site, and overall state of immunodeficiency.145 Large cell immunoblastic lymphomas are the most common (see Figure 26-28).15 Many AIDS-associated large cell lymphomas represent polyclonal proliferation suggestive of lymphokine-induced expansion of a B-cell population.226 In addition, most patients with HIV infection and NHL present with advanced disease; 90% have extranodal disease at presentation, and more than 50% present with stage IV disease.133,143 Age older than 35 years, advanced stage at diagnosis, and a CD4 count of less than 100 cells/mm3 are adverse prognostic factors. HAART is associated with a decreased incidence of NHL and an improved prognosis.162 The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of extranodal NHL, and in approximately 25% of the time, the gastrointestinal tract is the only site of disease.127 More than 90% of these lymphomas are B-cell lymphomas, and Epstein-Barr virus expression is seen in the majority.147,234

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree