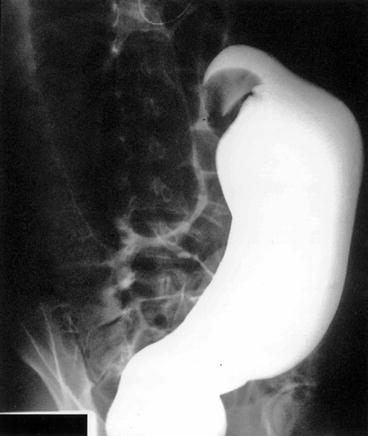

Fig. 23.1

Plain abdominal X-ray of sigmoid volvulus indicating the “bent inner-tube” sign

In up to 40 % of cases, the plain film can be equivocal: there may be superimposition of a distended transverse colon or small bowel, the sigmoid loop may be transversely oriented, or a massively dilated small bowel may mimic a sigmoid loop.

In these situations, a contrast enema or CT scan may clarify the diagnosis.

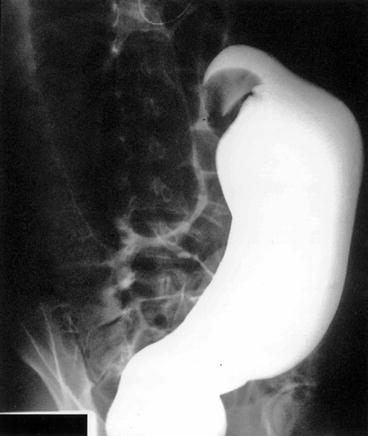

If a contrast enema is desired, it should be done with water-soluble contrast material, as the mortality with barium is very high if a perforation is encountered. A water-soluble contrast enema classically shows the contrast column ending sharply in a “bird’s beak” shape at the site of torsion (Fig. 23.2).

Fig. 23.2

Barium enema study of a sigmoid volvulus indicating the bird’s beak deformity and complete obstruction to retrograde flow of contrast

The major differential diagnoses that must be considered are obstruction due to colonic neoplasm and colonic ileus or Ogilvie’s syndrome, both of which can present in a similar way.

In the case of neoplasm, there may be a wisp of contrast through the lesion; if the obstruction is complete, the appearance is distinctly different from the classic “bird’s beak” appearance. In Ogilvie’s syndrome, the water-soluble contrast enema will show that there is no obstruction and may also be therapeutic.

Abdominal CT scan can be quite helpful in the identification of colonic volvulus. Much information has been written on the “whirl sign” indicating twisted mesentery and intestinal volvulus, although most reports refer to small bowel volvulus. More recent reports have noted that the “whirl sign” can be observed in settings other than intestinal volvulus and so may not be pathognomonic for intestinal volvulus.

In the pregnant patient, the diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus is usually made clinically, with subsequent endoscopic confirmation, or intraoperatively due to patient deterioration. The size of the uterus presents a challenge for operating in the pelvis; this makes simple detorsion or sigmoidopexy appear more attractive when the sigmoid colon is viable but exposes the patient to a high risk of recurrence and need for another, definitive operative procedure.

Treatment and Outcome

The first volvulus-specific maneuver in the stable patient with a sigmoid volvulus is attempted endoscopic detorsion.

Successful detorsion converts a surgical emergency into an elective situation.

If the patient is febrile or has localized tenderness over the distended loop, nonviable colon should be strongly suspected, and attempted detorsion should be abandoned. Attempted detorsion of nonviable bowel risks perforation and peritonitis, with the attendant complications thereof.

While detorsion was historically done with the rigid proctoscope, the flexible sigmoidoscope or colonoscope has replaced it as the instrument of choice.

When decompression is successful, as it is in 60–80 % of attempts, there is evacuation of significant flatus and stool with visible lessening of abdominal distention.

A decompressing tube may be placed into the detorsed loop to allow continued decompression and to prevent retorsion.

A plain abdominal film should then be obtained to confirm relief of volvulus and absence of intraperitoneal free air.

The high rate of revolvulus after detorsion alone, coupled with a mortality rate over 20 % for emergent surgery compared to 6 % or less with elective resection, has prompted most surgeons to proceed with elective sigmoid resection during the same hospitalization for most patients.

Complete colonoscopy should be performed prior to operation to rule out synchronous lesions that would alter management.

The standard elective surgical procedure is sigmoid resection with primary anastomosis, which may be accomplished with open technique or laparoscopic technique if the colon is sufficiently decompressed.

Patients successfully endoscopically decompressed prior to definitive resection have an incidence of recurrent volvulus close to zero.

However, in the setting of megacolon, total abdominal colectomy is the recommended procedure; otherwise, the patient is at very high risk of recurrent volvulus.

A number of nonresectional techniques have also been described for the treatment of sigmoid volvulus. These include surgical detorsion without resection or fixation or detorsion with methods of either sigmoid or mesenteric fixation.

The described techniques of sigmoid fixation include extraperitoneal sigmoidopexy, nonsurgical endoscopic sigmoidopexy with or without tube fixation, parallel colopexy to the transverse colon (Fig. 23.3), laparoscopic fixation, fixation of the sigmoid colon to the abdominal wall with bands of prosthetic with or without percutaneous colon deflation, and percutaneous endoscopic colostomy.

Fig. 23.3

Parallel colopexy as described by Mortensen

Mesenteric fixation techniques include mesosigmoplasty and mesenteric fixation (Fig. 23.4a, b).

Fig. 23.4

Mesosigmoidoplasty. (a) A longitudinal peritoneal incision made in the elongated, narrow mesentery. (b) The incision is then closed transversely, broadening the mesenteric base and shortening the height of the sigmoid loop

All nonresectional techniques are associated with high morbidity and/or high recurrence rate.

It is important to understand that the search for alternatives to resection for sigmoid volvulus was based on historical rates of morbidity and mortality.

Considering that modern surgical and anesthetic techniques have significantly reduced surgical complication rates, it seems clear that resection after decompression provides near-zero risk of recurrence with acceptable morbidity and mortality rates.

If endoscopic decompression is unsuccessful or visualizes gangrenous mucosa, the situation is a surgical emergency, and efforts at detorsion should be halted and preparation of the patient for surgery should be expeditiously done.

Exploration should be done via a midline laparotomy incision or potentially by laparoscopy if the patient is hemodynamically stable. If the bowel appears viable or possibly viable, the twist should be reduced.

The decision for anastomosis versus Hartmann’s procedure should be based on standard surgical criteria: the presence of good blood supply, absence of (or minimal) peritoneal soilage, reasonable nutritional status, and absence of shock would suggest that anastomosis is reasonable.

When considering stoma formation, it should be remembered that many of the stomas formed in this setting will be permanent, as infirm patients with other medical comorbidities will rarely become candidates for stoma closure. The usual maneuvers used for selecting stoma location are often difficult to employ preoperatively, given the abdominal contour and urgency of the patient’s situation. The bowel is often quite dilated, and a large opening in the abdominal wall may be required for a colostomy. This leads to a higher incidence of parastomal hernia.

Both morbidity and mortality are higher for emergent operations for sigmoid volvulus, compared to those for the elective or semi-elective setting. Deaths and complications increase further if gangrenous colon is encountered. Good outcomes can be achieved with primary anastomosis at the time of emergent sigmoidectomy for sigmoid volvulus with careful patient selection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree