Colon

4.1 Signet-ring cell change vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

4.2 Atypical stromal cells in polyps and ulcers vs. Sarcoma

4.3 Crohn colitis vs. Diverticular-associated colitis

4.4 Squeeze artifact vs. Ischemic colitis

4.5 Normal macrophages and foreign body granulomas vs. Granulomas typical of Crohn disease

4.6 Melanosis coli vs. Chronic granulomatous disease

4.7 Mastocytosis vs. Collagenous colitis

4.8 Ulcerative colitis vs. Self-limiting colitis

4.9 Ulcerative colitis vs. Crohn colitis

4.10 Sexually transmitted disease–associated proctocolitis vs. Inflammatory bowel disease

4.11 Pouchitis vs. Diversion colitis

4.12 Diversion colitis vs. Ulcerative colitis

4.13 Collagenous colitis vs. Thick basement membrane

4.14 Collagenous colitis vs. Radiation colitis

4.15 Collagenous colitis vs. Crohn colitis

4.16 Collagenous colitis vs. Amyloidosis

4.17 Amyloidosis vs. Thick basement membrane

4.18 Amyloidosis vs. Radiation colitis

4.19 Eosinophilic colitis vs. Mastocytosis

4.20 Mastocytosis vs. Langerhans cell histiocytosis

4.21 Ischemic colitis vs. Pseudomembranous colitis

4.22 Ischemic colitis vs. Thick basement membrane

4.23 Autoimmune colopathy vs. Normal colon

4.24 Common variable immunodeficiency vs. Normal colon

4.25 Kayexalate injury vs. Cholestyramine and related bile sequestrants

4.26 Mucosal prolapse polyps vs. Peutz-Jeghers polyps

4.27 Mucosal prolapse polyps vs. Sessile serrated adenoma

4.28 Mucosal prolapse polyps vs. Juvenile polyps

4.29 Juvenile polyps vs. Peutz-Jeghers polyps

4.30 Juvenile polyps vs. Adenomas

4.31 Juvenile polyps vs. Cronkhite-Canada polyp

4.32 Endometriosis vs. Sarcoma

4.33 Adenoma vs. Reparative changes

4.34 Colitis-associated dysplasia vs. Reactive changes

4.35 Colitis-associated dysplasia vs. Adenoma

4.36 Adenoma with invasive carcinoma vs. Pseudoinvasion

4.37 Neuroendocrine tumors vs. Colorectal carcinoma

4.38 Sessile serrated adenoma vs. Hyperplastic polyp

4.39 Sessile serrated adenoma vs. Traditional serrated adenoma

4.40 Smooth muscle tumors vs. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

4.41 Granular cell tumor vs. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

4.42 Ganglioneuroma vs. Schwann cell hamartoma

4.43 Neuroma vs. Schwann cell hamartoma

4.44 Perineurioma/fibroblastic polyp vs. Schwann cell hamartoma

4.45 Benign epithelioid nerve sheath tumor vs. Melanoma

4.46 Kaposi sarcoma vs. Lamina propria

4.47 Mantle cell lymphoma vs. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia

4.1 Signet-ring cell change vs. Signet-ring cell carcinoma

| Signet-Ring Cell Change | Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; males = females | Older adults (mean age 70s); male = female |

| Location | Any location | Any location |

| Symptoms | Related to any underling condition; can present with diarrhea and abdominal pain | Abdominal pain, alternating constipation and diarrhea, weight loss, GI bleeding |

| Signs | Related to any underlying condition; can present with abdominal tenderness or fever | Abdominal tenderness, positive fecal occult blood test |

| Etiology | Displacement and distortion of cells secondary to sloughing in the setting of mucosal damage often seen in association with pseudomembranous colitis | Variant of mucinous adenocarcinoma often associated with mutations in the APC, KRAS, and p53 genes; risk factors include diet, ethnicity, and genetic factors including several inherited syndromes such as HNPCC and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) |

| Histology | ||

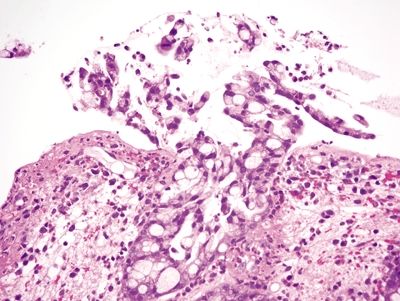

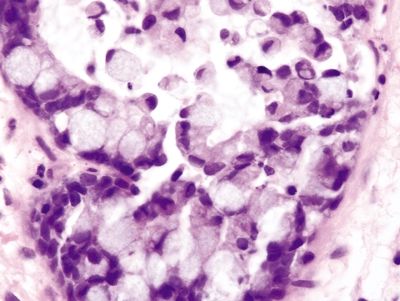

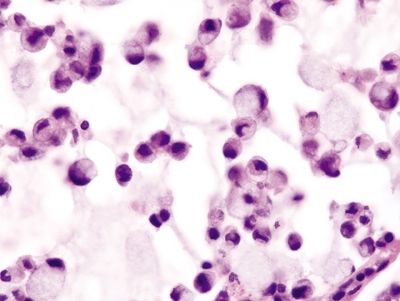

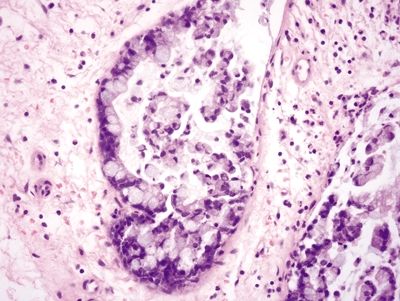

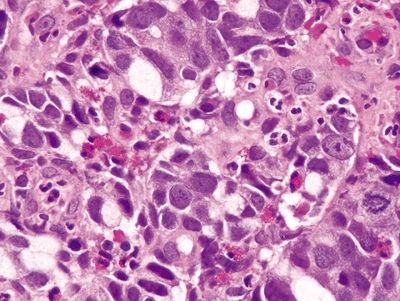

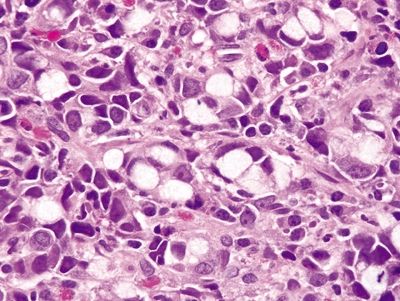

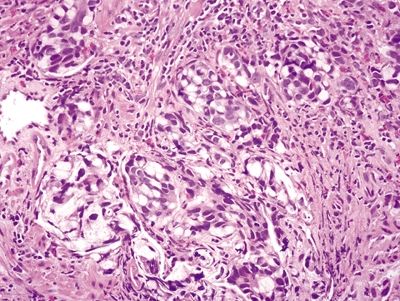

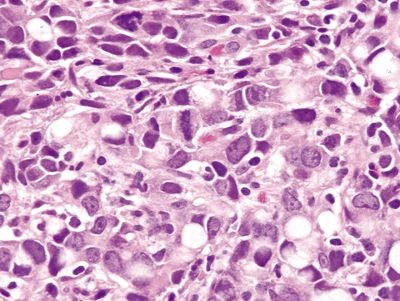

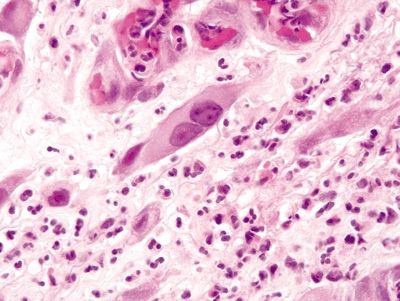

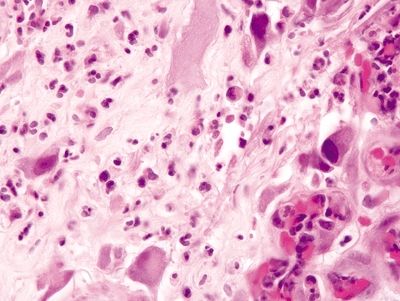

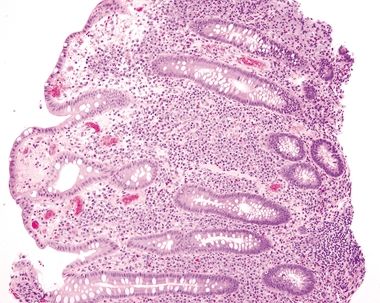

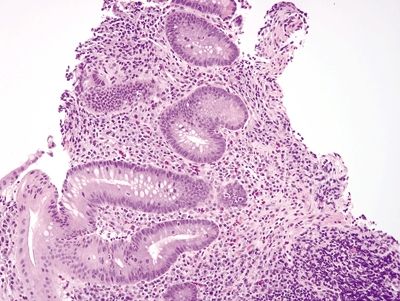

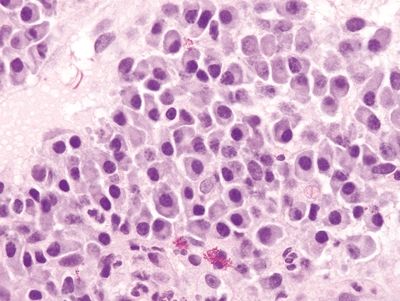

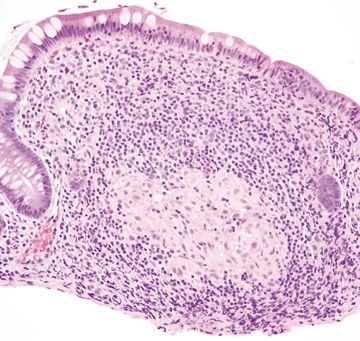

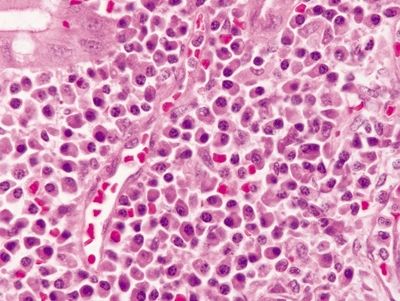

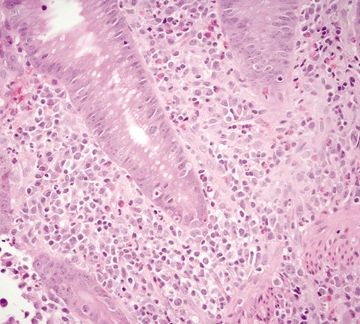

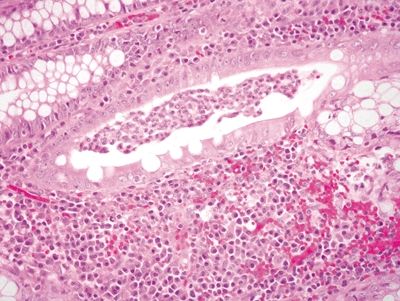

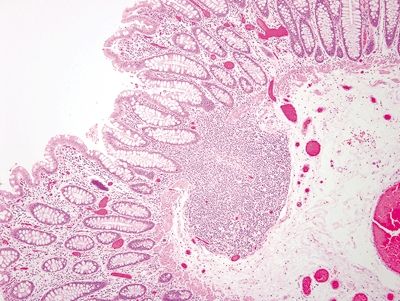

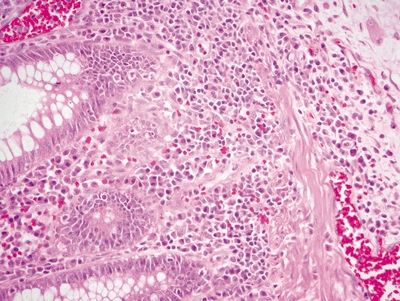

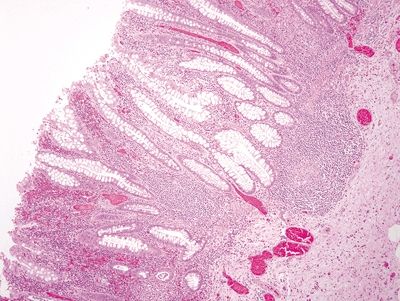

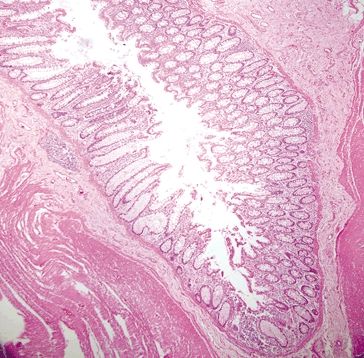

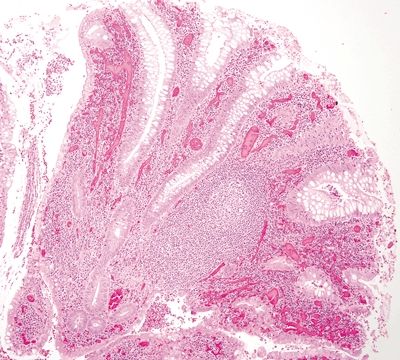

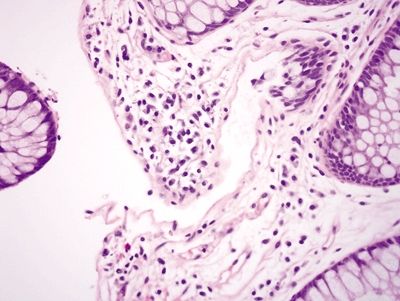

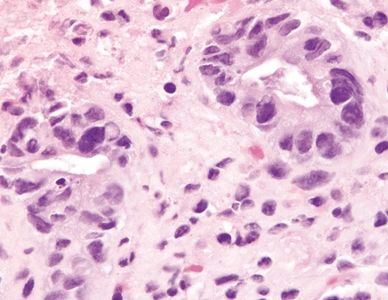

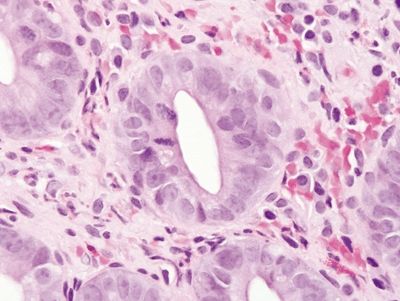

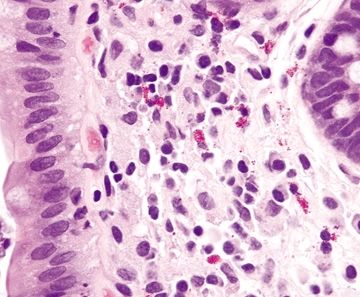

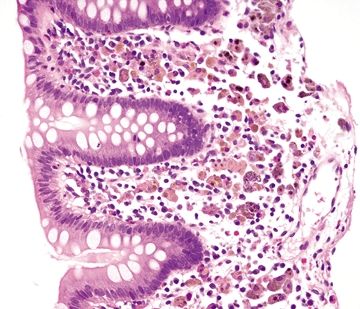

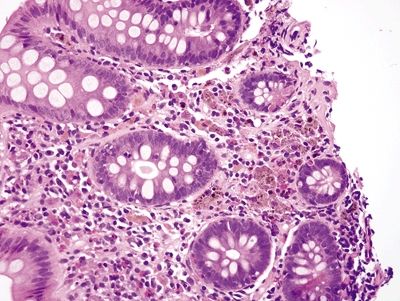

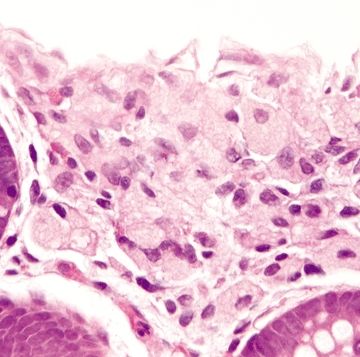

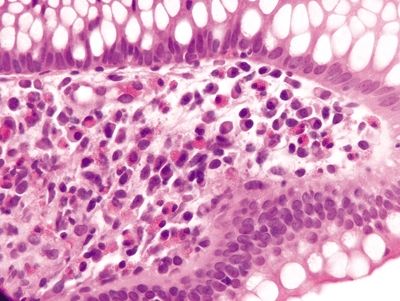

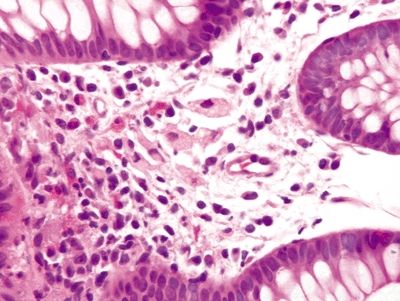

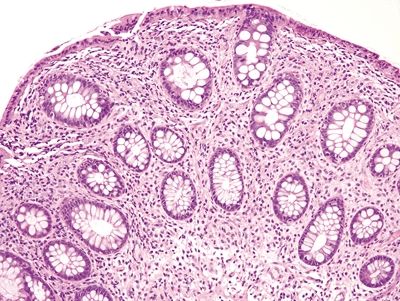

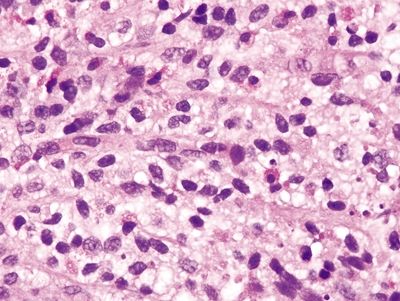

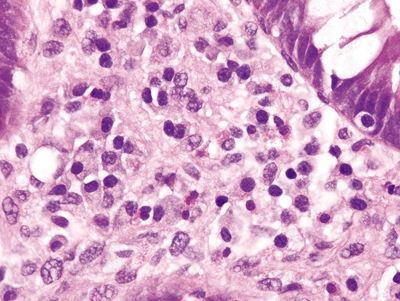

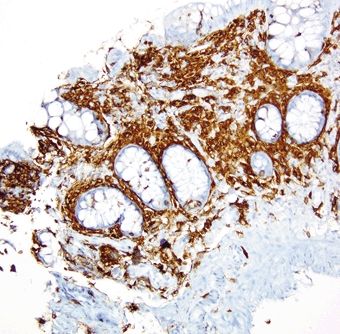

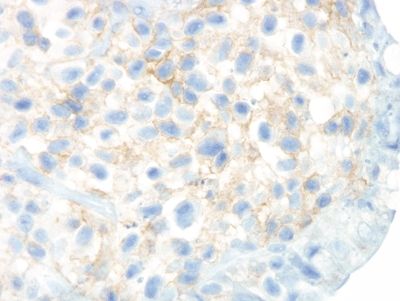

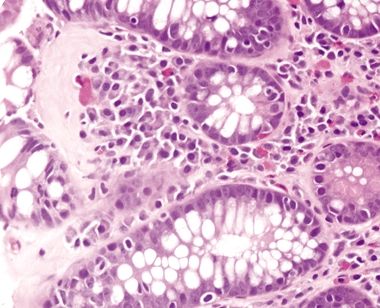

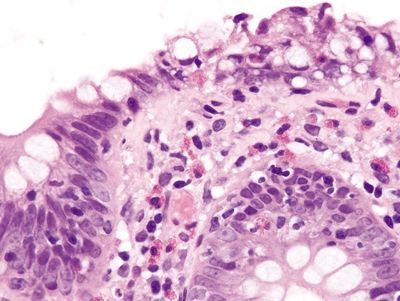

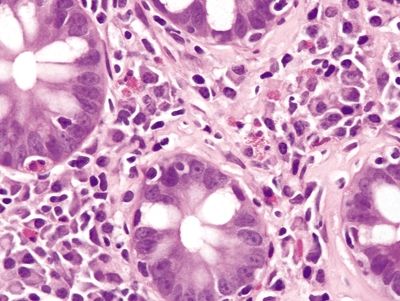

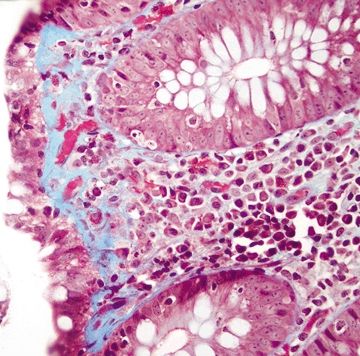

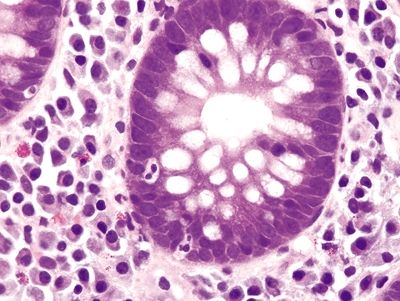

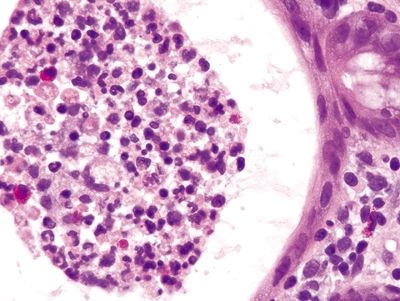

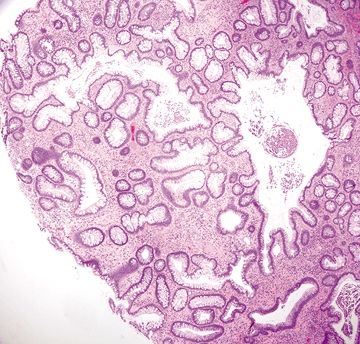

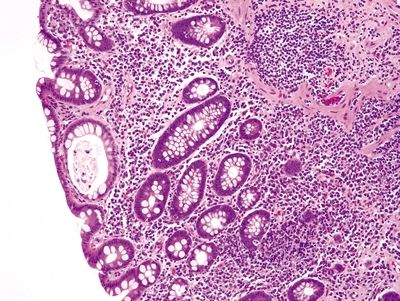

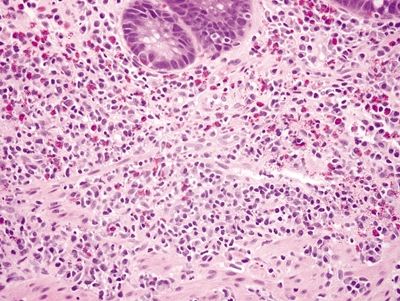

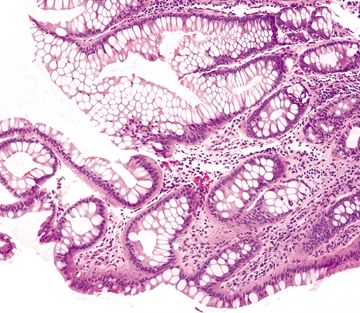

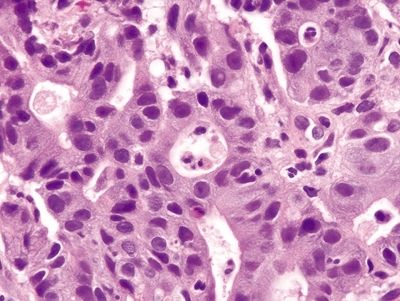

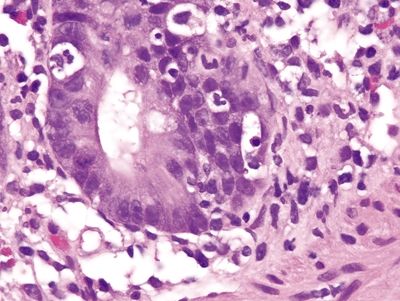

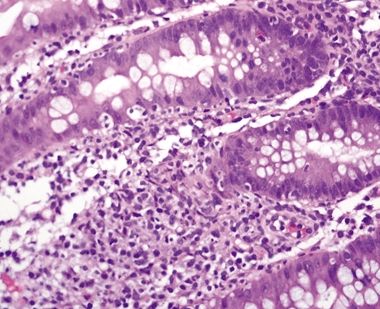

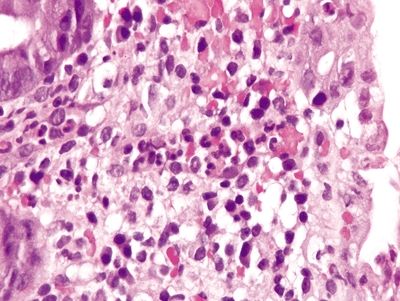

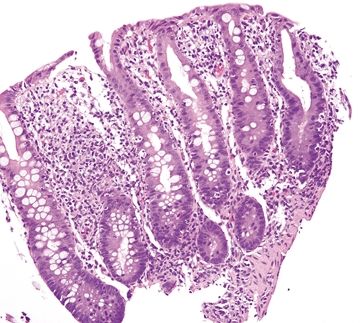

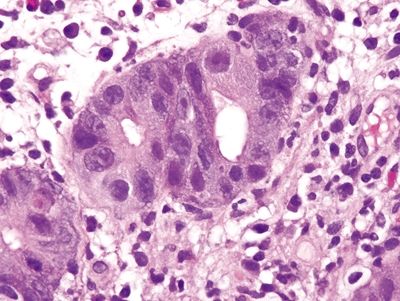

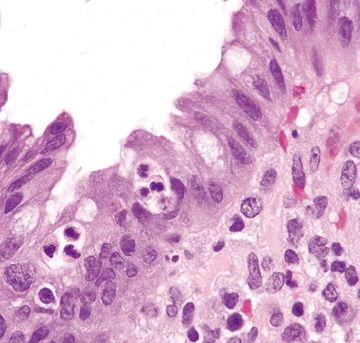

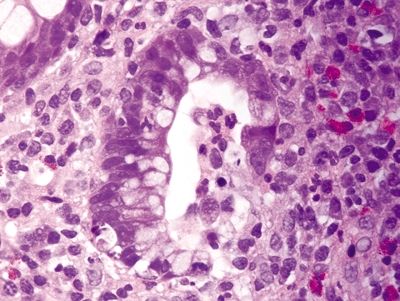

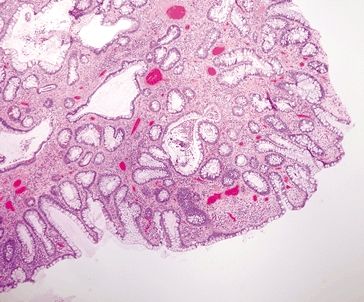

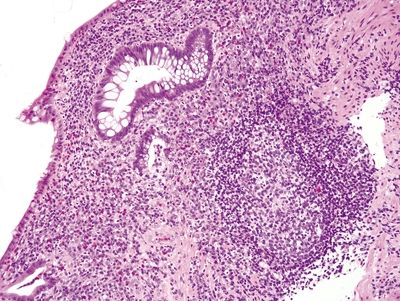

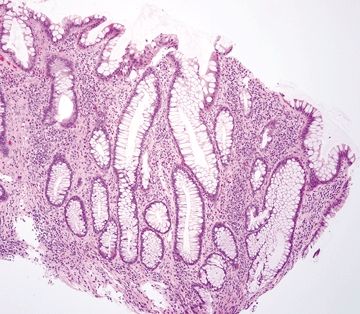

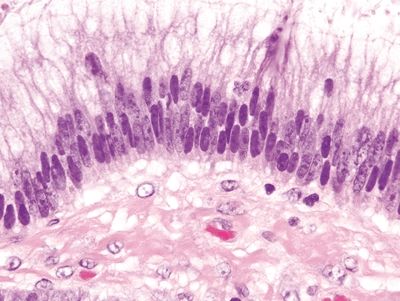

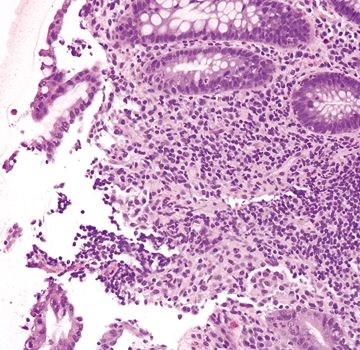

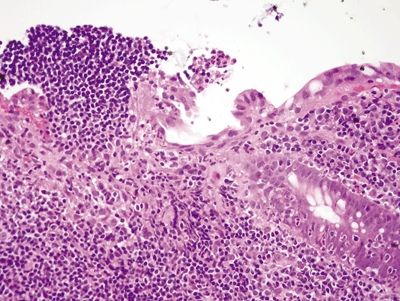

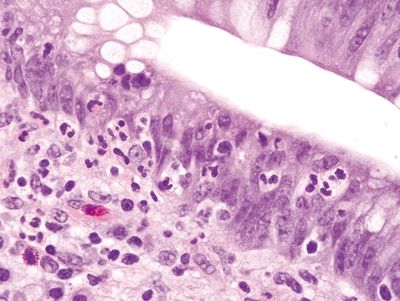

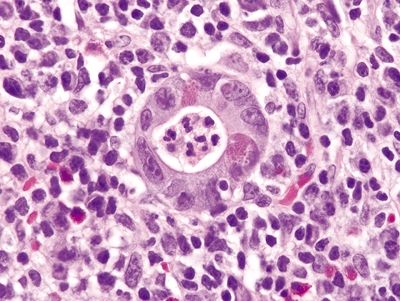

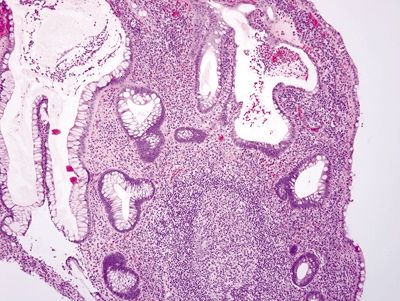

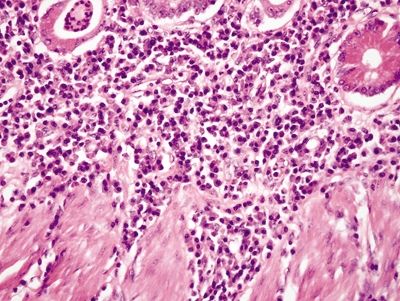

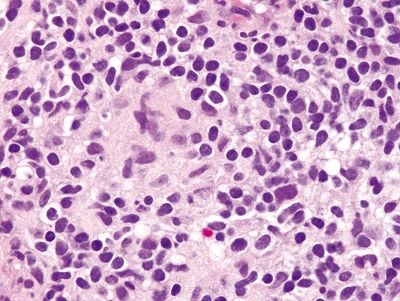

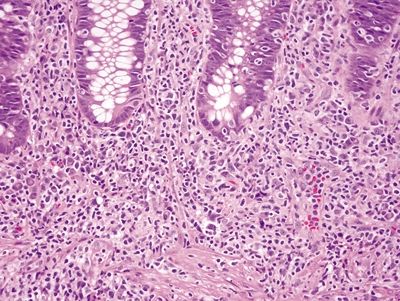

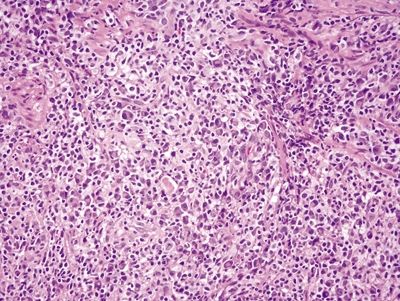

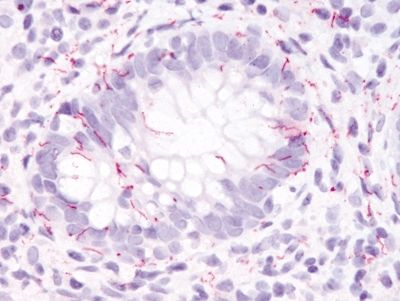

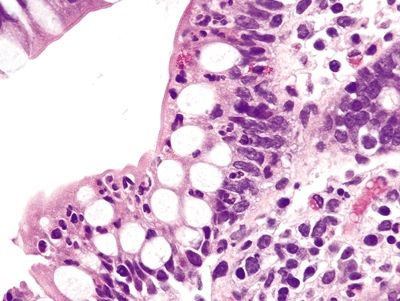

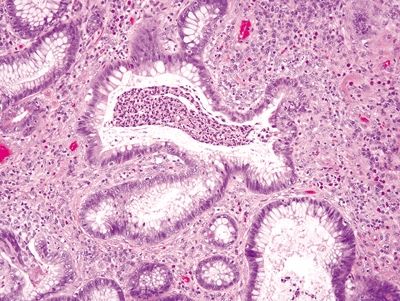

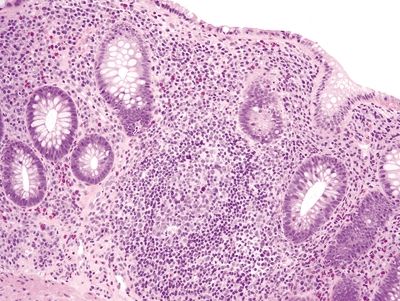

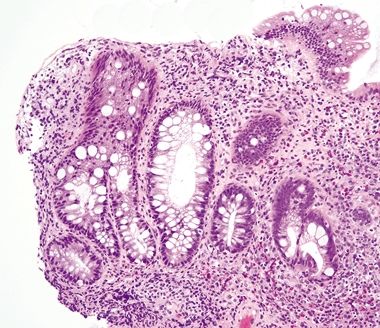

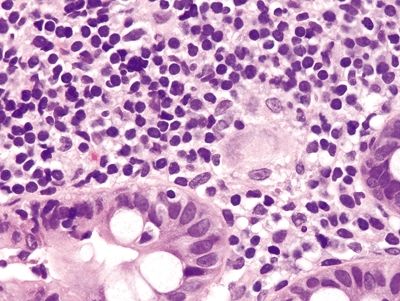

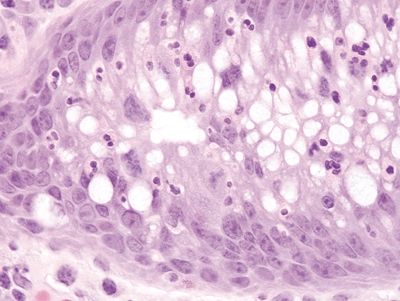

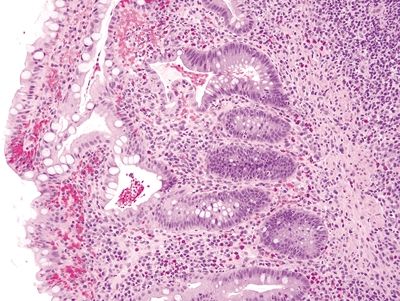

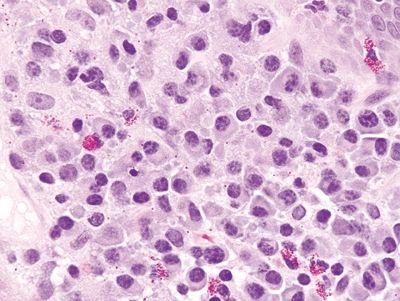

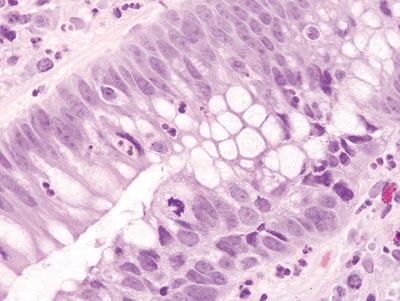

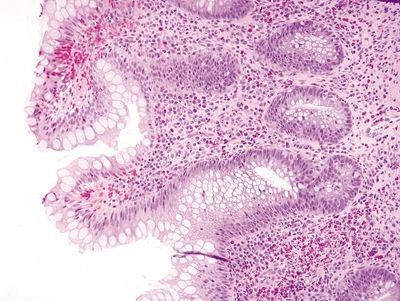

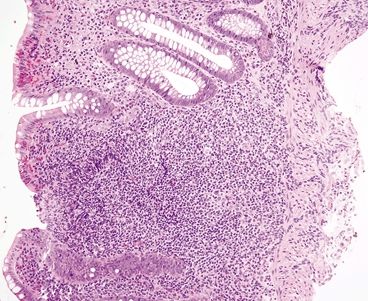

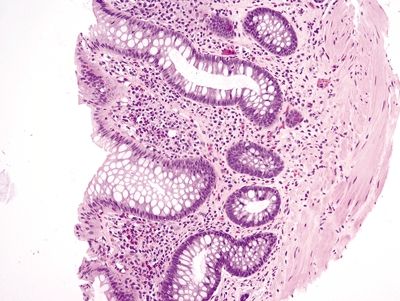

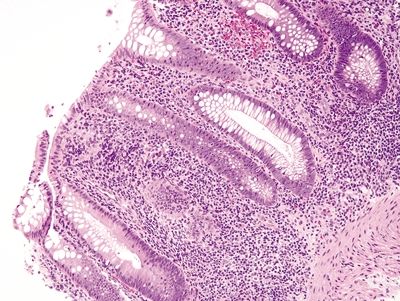

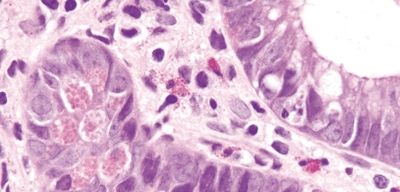

| 1. Background often shows features of pseudomembranous colitis characterized by a fibroinflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, mucus, and fibrin extending upward from the surface epithelium and focal epithelial necrosis (Fig. 4.1.1) 2. Sloughed epithelial cells congregate in the lumen and become distorted such that the intracytoplasmic mucin vacuole displaces the nucleus imparting a signet-ring cell appearance (Figs. 4.1.2 and 4.1.3) 3. Signet ring cells contained within the basement membrane of the glands; no extension into the lamina propria (Fig. 4.1.4) 4. Minimal nuclear atypia (Fig. 4.1.3) 5. Few to no mitoses or apoptotic bodies (Fig. 4.1.3) | 1. Minimal to no background inflammation unless associated with ulceration (Fig. 4.1.5) 2. Proliferation of dyscohesive signet ring cells with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 4.1.6) 3. Malignant cells infiltrate through the basement membrane into the lamina propria and often into the submucosa and deeper tissues; extravasated mucin with entrapped signet ring cells within the submucosa and muscularis propria are often present (Fig. 4.1.7) 4. Prominent nuclear atypia (Figs. 4.1.5 and 4.1.6) 5. Frequent mitoses (Fig. 4.1.8) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Specific to any underlying etiology | Surgical resection with adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced-stage disease |

| Prognosis | Varies; related to any underlying etiology | Fair to poor; prognosis related to stage and grade of the tumor. Most patients with signet-ring cell carcinoma present at an advanced stage, and many present with lymph node metastases |

Figure 4.1.1 Signet ring cell change. Mucosal ulceration with acute and chronic inflammation and distortion of the residual glands with extruded signet ring cells.

Figure 4.1.2 Signet ring cell change. Sloughed epithelial cells congregating within the gland lumen.

Figure 4.1.3 Signet ring cell change. Extruded signet ring cells with minimal to no nuclear atypia.

Figure 4.1.4 Signet ring cell change. Signet ring cells contained within the basement membrane of the gland.

Figure 4.1.5 Signet ring cell carcinoma. Markedly atypical signet ring cells seen in association with acute inflammation secondary to ulceration.

Figure 4.1.6 Signet ring cell carcinoma. Dyscohesive signet ring cells with pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli.

Figure 4.1.7 Signet-ring cell carcinoma infiltrating the muscularis propria.

Figure 4.1.8 Signet-ring cell carcinoma with marked atypia and prominent mitoses.

4.2 Atypical stromal cells in polyps and ulcers vs. Sarcoma

| Atypical Stromal Cells in Polyps and Ulcers | Sarcoma (or other malignant spindle cell lesions) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; males = females | Any age; any location |

| Location | Any location | Any location |

| Symptoms | Related to any underlying etiology, but often asymptomatic | Abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, GI bleeding |

| Signs | Related to any underlying etiology | Abdominal tenderness; radiologic studies may show a mass |

| Etiology | Reactive process in which reactive fibroblasts proliferate in response to mucosal injury; often seen in association with ulcers or polyps | Malignant transformation of mesenchymal components in the bowel wall |

| Histology | ||

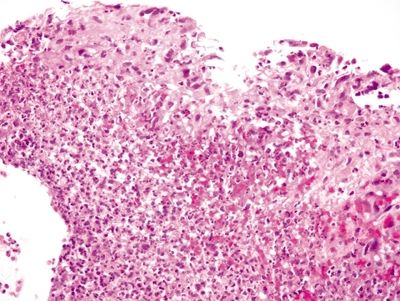

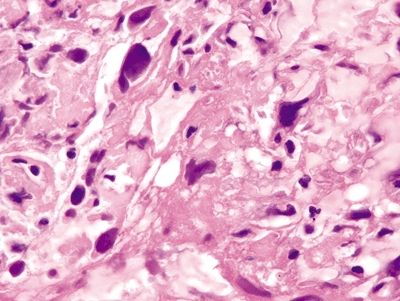

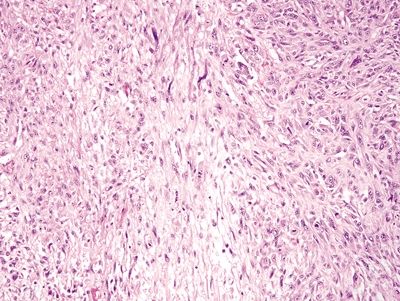

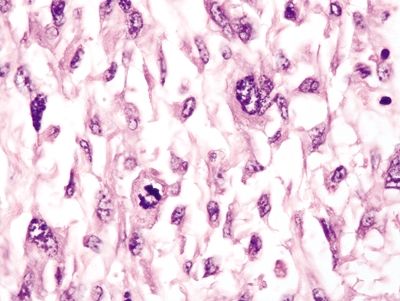

| 1. Bizarre; markedly atypical cells characterized by nuclear enlargement, pleomorphism, and/or multinucleation often with prominent nucleoli, smudgy chromatin, and ample eosinophilic cytoplasm (low N/C ratio) (Figs. 4.2.1 and 4.2.2) 2. Background ulceration and acute inflammatory exudate with atypical cells arranged in a monolayer at the interface between granulation tissue and necroinflammatory debris; no mass formation (Fig. 4.2.3) 3. Mitoses can be present, with rare atypical mitotic figures | 1. Proliferation of spindle to epithelioid cells with enlarged, pleomorphic nuclei, scant to moderate cytoplasm (high N/C ratio), and often prominent nucleoli (Fig. 4.2.4) 2. Malignant cells arranged in clusters and sheets that form a mass, not in a monolayer (Fig. 4.2.5) 3. Mitoses usually prominent, atypical mitoses readily identified (Fig. 4.2.6) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | None | Surgical excision followed by adjuvant therapy if indicated |

| Prognosis | Excellent, benign finding with no clinical significance | Variable, related to the type and stage of sarcoma |

Figure 4.2.1 Atypical stromal cells (reactive). Markedly atypical cells with enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and ample eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Figure 4.2.2 Atypical stromal cells. Markedly atypical stromal cells with hyperchromatic enlarged nuclei and prominent cytoplasm.

Figure 4.2.3 Atypical stromal cells at the base of an ulcer bed.

Figure 4.2.4 Infiltrating sarcomatoid lung carcinoma with markedly atypical, hyperchromatic cells with scant cytoplasm.

Figure 4.2.5 Leiomyosarcoma arranged as sheets of cells.

Figure 4.2.6 Markedly atypical cells of sarcomatoid lung carcinoma with a prominent mitosis.

4.3 Crohn colitis vs. Diverticular-associated colitis

| Crohn Colitis | Diverticular-Associated Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (20s–30s and 60s–70s); no gender predominance | Older adults (60s); male = female |

| Location | Usually prominent in the proximal colon; rectum is often spared | Restricted to sigmoid colon |

| Symptoms | Cramping abdominal pain, nonbloody diarrhea, fever, fatigue, weight loss | Hematochezia is common |

| Signs | Hypoalbuminemia, iron deficiency anemia, fistulas, and stenosis; extraintestinal manifestations affect the liver, eyes, and joints; endoscopic features include aphthous erosions, longitudinal ulcers, cobblestoning, strictures, and fistulas | Positive fecal occult blood test; colonoscopy shows patchy hyperemia |

| Etiology | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasians and Ashkenazi Jews; 10% of patients have an affected family member | Unknown; thought to be an immunologic disorder but the lesions could represent spread of inflammation from within diverticula to adjacent mucosa of redundant folds |

| Histology | ||

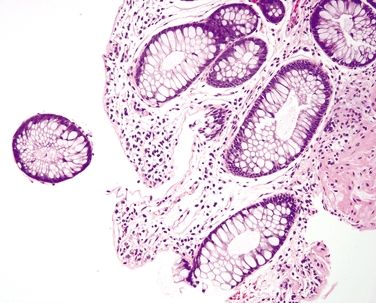

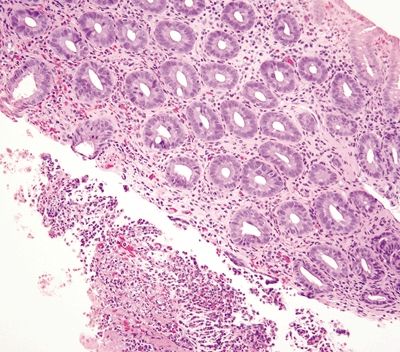

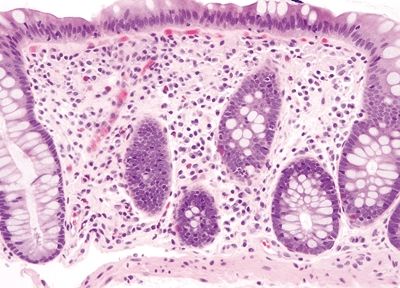

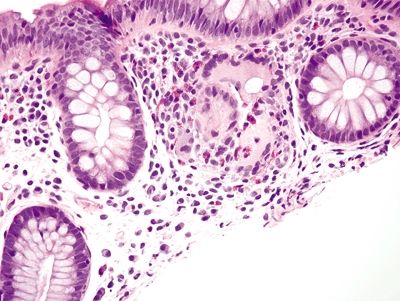

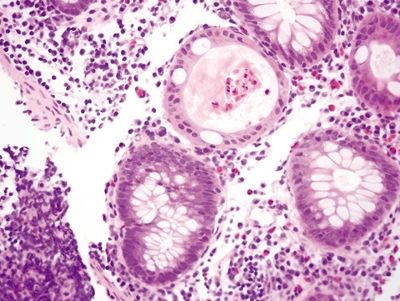

| 1. Focal surface epithelial injury characterized by epithelial necrosis (Fig. 4.3.1) with a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate often associated with a lymphoid aggregate (aphthous ulcers) and discrete foci of cryptitis (neutrophils within crypts) (Fig. 4.3.2) 2. Transmural inflammation, often more pronounced in the submucosa (Fig. 4.3.3) 3. Chronic changes include crypt distortion (Fig. 4.3.4), basal plasmacytosis (Fig. 4.3.5), and fibrosis, which extends deep into the lamina propria 4. Discontinuous involvement—areas with inflammatory changes adjacent to unaffected areas; no association of inflammation with distribution of diverticula 5. Rare poorly formed granulomas with associated chronic inflammation (Fig. 4.3.6) | 1. Expansion of the lamina propria by an inflammatory infiltrate consisting of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils (Fig. 4.3.7) 2. Neutrophilic cryptitis (Fig. 4.3.8) and crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.3.9) 3. Basal lymphoid aggregates (Fig. 4.3.10) and basal plasmacytosis (Fig. 4.3.11) 4. Crypt distortion (Fig. 4.3.12) 5. Focal Paneth cell metaplasia is often present 6. Some have granulomatous cryptitis 7. Inflammatory changes are only seen in association with diverticula; biopsies from rectal mucosa are histologically unremarkable (Figs. 4.3.13 and 4.3.14) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies; surgical resection is generally avoided unless necessary for complications including fissures, fistulas, obstruction | Antibiotics and fiber diet, as well as anti-inflammatory therapies and/or surgical resection for severe cases |

| Prognosis | Fair; chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma associated with an 80% mortality rate | Good; most cases resolve with antibiotic therapy |

Figure 4.3.1 Focal surface epithelial injury with erosion and associated neutrophils in Crohn colitis.

Figure 4.3.2 Cryptitis and crypt abscesses in Crohn colitis.

Figure 4.3.3 Marked mucosal inflammation in Crohn colitis.

Figure 4.3.4 Prominent chronic inflammation within the lamina propria with a lymphoid aggregate and crypt distortion in Crohn colitis.

Figure 4.3.5 Basal plasmacytosis in Crohn colitis. These plasma cells are found between the bases of the crypts and the muscularis mucosae.

Figure 4.3.6 Mucosal granuloma in Crohn colitis.

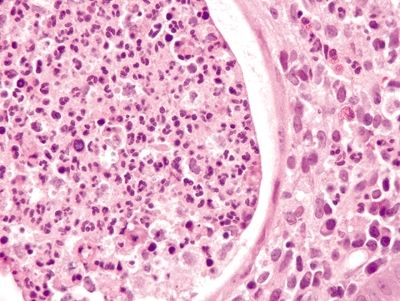

Figure 4.3.7 Diverticular disease-associated colitis. Marked chronic inflammation, predominantly plasma cells, in the lamina propria.

Figure 4.3.8 Cryptitis in diverticular-associated colitis.

Figure 4.3.9 Crypt abscess in diverticular-associated colitis.

Figure 4.3.10 Submucosal lymphoid aggregate in diverticular-associated colitis.

Figure 4.3.11 Marked basal plasmacytosis in diverticular-associated colitis.

Figure 4.3.12 Crypt distortion and marked chronic inflammation in diverticular-associated colitis.

Figure 4.3.13 Background diverticulum in diverticular-associated colitis.

Figure 4.3.14 Marked chronic inflammation and prominent lymphoid aggregates expanding the lamina propria in diverticular-associated colitis.

4.4 Squeeze artifact vs. Ischemic colitis

| Squeeze Artifact | Ischemic Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; male = female | Usually adults (50s or older), but can occur in children; male = female |

| Location | Any location; usually at the edges of the specimen | Most common in watershed regions (e.g., splenic flexure), descending colon, and sigmoid colon, but can occur at any location; rectum is least affected |

| Symptoms | None | Variable; some present with abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody diarrhea |

| Signs | None | Variable; some present with abdominal tenderness, fever, positive fecal occult blood test; many have a history of cardiovascular disease with signs of peripheral vascular disease or other vascular diseases; barium enema shows characteristic “thumb printing”; CT scan can show “target lesions,” and angiography can be used to directly identify vascular obstruction |

| Etiology | An artifact of the biopsy procedure and specimen processing due to physical trauma caused by the biopsy forceps, which displace the epithelium from the crypts | Mucosal damage secondary to decreased blood flow often due to obstruction (e.g., atherosclerosis, vasospasm, thrombus), hypovolemia, and hypoperfusion (i.e., low cardiac output). It can also occur due to drugs and infection. Risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, COPD, coronary artery disease, abdominal surgery, use of opioids, antihypertensives, hormone replacement therapy, performance-enhancing supplements, and immunomodulators |

| Histology | ||

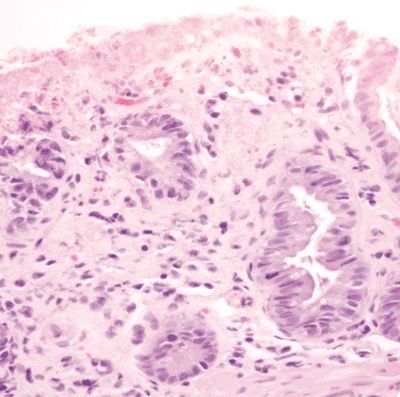

| 1. Empty crypts (Fig. 4.4.1) with displaced glands usually detached and adjacent to the specimen and appear histologically unremarkable (Fig. 4.4.2) 2. No changes in the lamina propria 3. Residual crypts unaffected 4. Minimal to no atypia 5. No mitoses 6. No inflammation or pseudomembranes | 1. Superficial mucosal necrosis with loss of the surface epithelium but preservation of the deep crypts (Fig. 4.4.3) 2. Hyalinization of the lamina propria, with occasional hemorrhage 3. Residual crypts are atrophic and appear closer together (lamina propria “collapse”) (Fig. 4.4.4) 4. Often marked regenerative atypia characterized by enlarged, hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and loss of mucin (Fig. 4.4.5) 5. Mitoses often conspicuous; atypical mitoses can be seen (Fig. 4.4.6) 6. May have pseudomembranes (Fig. 4.4.7) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | None | Supportive care; surgical resection for severe or complicated disease |

| Prognosis | Related to any underlying pathology | Good; most resolve with supportive care, though a subset require surgical resection due to complications, including perforation, peritonitis, and strictures |

Figure 4.4.1 Empty crypt in squeeze artifact.

Figure 4.4.2 Squeeze artifact showing empty crypt with displaced epithelium adjacent to the crypt.

Figure 4.4.3 Focal superficial mucosal erosion and reactive epithelial changes in ischemic colitis.

Figure 4.4.4 Hyalinization of the lamina propria with back-to-back crypts in ischemic colitis.

Figure 4.4.5 Marked reactive epithelial changes in ischemic colitis.

Figure 4.4.6 Prominent reactive epithelial changes and mitoses in ischemic colitis.

Figure 4.4.7 Hyalinization of the lamina propria in association with a fibrinopurulent exudate in ischemic colitis.

4.5 Normal macrophages and foreign body granulomas vs. Granulomas typical of Crohn disease

| Normal Macrophages and Foreign Body Granulomas | Granulomas Typical of Crohn Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; no gender predominance | Typically adults (20s–30s and 60s–70s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Any location | Usually prominent in the proximal colon; rectum is often spared |

| Symptoms | Usually none; some patients may present with abdominal pain | Cramping abdominal pain, nonbloody diarrhea, fever, fatigue, weight loss |

| Signs | Usually none; some patients present with abdominal tenderness | Hypoalbuminemia, iron deficiency anemia, fistulas, and stenosis; extraintestinal manifestations affect the liver, eyes, and joints; endoscopic features include aphthous erosions, longitudinal ulcers, cobblestoning, strictures, and fistulas |

| Etiology | Reaction to foreign material | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasian and Ashkenazi Jews; 10% of patients have an affected family member |

| Histology | ||

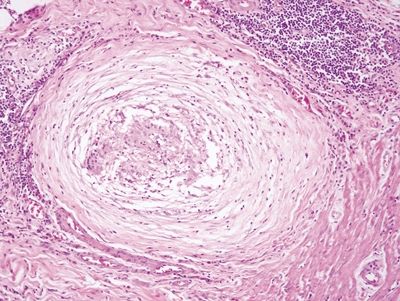

| 1. Normal macrophages: aggregate in the superficial lamina propria beneath the surface epithelium (Figs. 4.5.1 and 4.5.2) 2. Aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes mixed with foreign body–type multinucleated giant cells composed of up to 20 nuclei haphazardly arranged and often overlapping (Figs. 4.5.3 and 4.5.4) 3. Giant cells usually seen in reaction to a ruptured crypt but foreign material can be seen within the aggregate of histiocytes either with light microscopy or under polarized light 4. Minimal to no background inflammation and no features of chronicity | 1. Poorly formed and associated with chronic inflammation (Fig. 4.5.5) 2. Nonnecrotizing 3. No foreign material seen a. Background features of Crohn disease b. Focal surface epithelial injury characterized by epithelial necrosis with a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate often associated with a lymphoid aggregate (aphthous ulcers) and discrete foci of cryptitis c. Transmural inflammation, often more pronounced in the submucosa d. Chronic changes include crypt distortion and fibrosis, which extends deep into the lamina propria e. Discontinuous involvement—areas with inflammatory changes adjacent to unaffected areas | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | None to surgical excision for complications | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies; surgical resection for complications including fissures, fistulas, obstruction |

| Prognosis | Good; most are incidental findings; however, some are associated with complications such as persistent abdominal pain, obstruction, or perforation and require surgical intervention | Chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma associated with an 80% mortality rate. |

Figure 4.5.1 Normal macrophages primarily distributed beneath the epithelium.

Figure 4.5.2 Macrophages intermixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria of the colon.

Figure 4.5.3 Ruptured crypt with surrounding histiocytic reaction.

Figure 4.5.4 Ruptured crypt with prominent eosinophils and foreign body giant cell reaction.

Figure 4.5.5 Loosely formed granuloma in Crohn disease characterized a collection of histiocytes with associated lymphocytes.

4.6 Melanosis coli vs. Chronic granulomatous disease

| Melanosis Coli | Chronic Granulomatous Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Adults; male = female | Infants to young children; male > female (10:1) |

| Location | Most common in the cecum and rectum; can occur in any location | Anywhere in the colorectum. Findings classically described in the lung |

| Symptoms | None | Recurrent bacterial and fungal infections |

| Signs | None | Fever |

| Etiology | Deposition of lipofuscin in macrophages, which is most often seen in association with laxative use, with a particularly strong association with anthraquinone and other laxatives that induce apoptosis; also seen in association with NSAID use and inflammatory bowel disease | Inherited immune deficiency disorder caused by mutations in any of the genes that encode for proteins of the superoxide-generating phagocyte NADPH oxidase system involved in the elimination of organisms ingested by neutrophils |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Prominent pigment-laden macrophages within the lamina propria (Figs. 4.6.1 and 4.6.2) 2. Eosinophils not prominent 3. No abscess formation | 1. Lamina propria replaced by poorly formed granulomas (Fig. 4.6.3) or loose clusters of macrophages 2. Prominent eosinophils (Fig. 4.6.4) 3. Macrophages often pigmented (Fig. 4.6.5) 4. Rare abscess formation | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | None | Prophylactic and infection-specific antibiotics, interferon gamma, bone marrow transplantation, and gene therapy |

| Prognosis | Excellent; incidental benign finding | Poor; patients have recurrent infections, and complications are associated with significant morbidity and mortality with an average life expectancy of 25–30 years |

Figure 4.6.1 Brown-pigmented macrophages infiltrating the lamina propria with no changes in the background mucosa of melanosis coli.

Figure 4.6.2 Dark brown to black pigmented macrophages within the lamina propria of melanosis coli.

Figure 4.6.3 Poorly formed granuloma composed of pigmented histiocytes in chronic granulomatous disease.

Figure 4.6.4 Prominent eosinophils in the lamina propria in chronic granulomatous disease.

Figure 4.6.5 Lightly pigmented histiocytes scattered within the lamina propria in chronic granulomatous disease.

4.7 Mastocytosis vs. Collagenous colitis

| Mastocytosis | Collagenous Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; any gender | Typically adults (mean age 55); female predominant (6–8:1) |

| Location | Any location | Most prominent in the proximal colon; less prominent in the rectosigmoid |

| Symptoms | Nonspecific; in systemic mastocytosis, patients can present with symptoms related to increased histamine secretion, while in localized mastocytosis, patients often have chronic diarrhea; patients may present with symptoms related to increased histamine secretion | Chronic watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss; some may have constipation |

| Signs | None | Few, if any; endoscopic evaluation is usually normal; rarely shows linear ulcers or pseudomembranes |

| Etiology | Unknown; some cases are associated with inflammatory disease including allergic disease, parasitic infections, and eosinophilic colitis, while other cases are manifestations of systemic mastocytosis. So-called “mastocytic enterocolitis” is probably not an entity but was described in patients with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome | Unknown; thought to be related to an immunologic response to a luminal antigen; up to 40% of patients have an associated disease, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disorders, celiac disease; some cases are related to medications including lansoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, and NSAIDs; rare cases are associated with procedure-related perforation |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Few to no surface epithelial changes (Fig. 4.7.1) 2. Increased mast cells with round, basophilic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm in the lamina propria (Fig. 4.7.2) 3. Increased eosinophils in the lamina propria; no infiltration of the surface or crypt epithelium (Fig. 4.7.3) 4. No increase in subepithelial collagen (Fig. 4.7.1) | 1. Surface epithelial injury characterized by intraepithelial lymphocytes with associated cellular degeneration including cytoplasmic vacuoles, mucin loss, irregular nuclear contours, and pyknosis (Figs. 4.7.6 and 4.7.7) 2. No increase in mast cells 3. Expansion of the lamina propria by an infiltrate of plasma cells and lymphocytes and often neutrophils (in lymphocytic colitis); increased eosinophils within the lamina propria and within the surface and crypt epithelium (Fig. 4.7.8) 4. Subepithelial deposition of collagen beneath the surface epithelium, usually 10–30 μm, which has an irregular lower border and extends into the lamina propria in association with dilated capillaries and fibroblasts (Figs. 4.7.7 and 4.7.9); intermittent separation of the surface epithelium from the basement membrane (collagenous colitis) (Fig. 4.7.9) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Mainstay of treatment is histamine receptor antagonists and cromolyn sodium, a mast cell mediator–release inhibitor | Varies, from none to symptomatic and/or anti-inflammatory therapy and diverting ileostomy for refractory disease |

| Prognosis | Generally good; systemic disease and the prognosis is related to morbidity of involvement of other sites | Generally good; some cases resolve spontaneously; most other cases respond well to therapy; Paneth cell metaplasia may portend a worse prognosis |

Figure 4.7.1 Systemic mastocytosis involving the lamina propria with few surface epithelial changes and no basement membrane thickening.

Figure 4.7.2 Systemic mastocytosis. Increased mast cells within the lamina propria.

Figure 4.7.3 Systemic mastocytosis. Increased eosinophils within the lamina propria.

Figure 4.7.4 Systemic mastocytosis. CKIT stain highlighting increased mast cells within the lamina propria.

Figure 4.7.5 Systemic mastocytosis. CD25 stain highlighting aberrant expression by abnormal mast cells.

Figure 4.7.6 Surface epithelial injury with intraepithelial lymphocytes seen in adjacent to a thickened basement membrane in collagenous colitis.

Figure 4.7.7 Surface epithelial injury with prominent intraepithelial lymphocytes and cytoplasmic vacuoles associated with a thickened basement membrane that entraps capillaries and inflammatory cells in collagenous colitis.

Figure 4.7.8 Collagenous colitis. Mixed inflammation in the lamina propria composed of plasma cells and prominent eosinophils in collagenous colitis.

Figure 4.7.9 Thickened basement membrane with focal epithelial detachment in collagenous colitis.

Figure 4.7.10 Collagenous colitis. Trichrome stain highlighting thickened basement membrane, which extends into the lamina propria and entraps capillaries and lymphocytes.

4.8 Ulcerative colitis vs. Self-limiting colitis

| Ulcerative Colitis | Self-Limiting Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (15–25 and 60s–70s); no gender predominance | Any age; either gender. |

| Location | Involves the rectum and extends proximally | Any location |

| Symptoms | Recurrent bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss | Diarrhea, hemorrhagic with certain organisms. |

| Signs | Varies from few to fever and tachycardia associated with toxic megacolon; endoscopic findings are variable: active phase—erythematous, friable, granular mucosa, quiescent phase—granular mucosa with punctate erythema and loss of haustral folds; polyps | Positive stool culture |

| Etiology | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasians and Ashkenazi Jews; 25% of patients have an affected relative | Inflammation secondary to bacterial infection most commonly due to Campylobacter sp. and Aeromonas sp. (except enterohemorrhagic E. coli) |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Active disease characterized by cryptitis (Fig. 4.8.1) and crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.8.2) often in association with pseudopolyps characterized by heaps of mucosa surrounded by extensive ulceration (Fig. 4.8.3); neutrophils predominantly within crypts not in the lamina propria 2. Increased mucosal chronic inflammation with lymphoid aggregates often prominent at the mucosal–submucosal interface (Fig. 4.8.4) and basal plasmacytosis (Fig. 4.8.5) 3. Chronic changes include crypt distortion (Fig. 4.8.6) and background reactive and regenerative epithelial changes (Fig. 4.8.7); minimal to no fibrosis in the submucosa 4. Dysplasia can be seen | 1. Prominent neutrophilic infiltrate most prominent in the upper half of the lamina propria and within crypts (Figs. 4.8.8–4.8.10) 2. No marked increase in chronic inflammation or basal plasmacytosis 3. Preserved glandular architecture; no crypt distortion (Fig. 4.8.11) 4. Reactive epithelial changes with enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and mucin loss, but no dysplasia (Fig. 4.8.12) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory drugs including 5-ASA compounds and steroids. Routine surveillance colonoscopy to screen for dysplasia and/or adenocarcinoma is recommended for patients with extensive disease for longer than 8 years. Surgical resection for high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma | Antibiotics |

| Prognosis | Fair; chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to the extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Patients are at increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, and there is a small but measurable risk of early mortality due to toxic colitis as well as other complications | Excellent; the colitis is self-limiting |

Figure 4.8.1 Cryptitis in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.8.2 Crypt abscess in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.8.3 Pseudopolyp in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.8.4 Marked chronic inflammation within the lamina propria with a lymphoid aggregate at the mucosal–submucosal interface in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.8.5 Basal plasmacytosis in ulcerative colitis. The plasma cells are present between the bases of the crypts and the muscularis mucosae

Figure 4.8.6 Crypt distortion in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.8.7 Ulcerative colitis. Marked reactive epithelial changes characterized by enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli and mucin loss.

Figure 4.8.8 Intraepithelial neutrophils and prominent crypt apoptosis in self-limiting colitis.

Figure 4.8.9 Prominent inflammatory infiltrate, predominantly neutrophils, in the upper half of the lamina propria and within glands and crypts in self-limiting colitis.

Figure 4.8.10 Neutrophilic infiltrate most prominent in the superficial lamina propria directly beneath the epithelium in self-limiting colitis. The surface is at the right.

Figure 4.8.11 No crypt distortion in self-limiting colitis.

Figure 4.8.12 Marked reactive changes in self-limiting colitis.

4.9 Ulcerative colitis vs. Crohn colitis

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults (15–25 and 60s–70s); no gender predominance | Typically adults (20s–30s and 60s–70s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Always involves the rectum and extends proximally | Usually prominent in the proximal colon; rectum is often spared |

| Symptoms | Recurrent bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss | Cramping abdominal pain, nonbloody diarrhea, fever, fatigue, weight loss |

| Signs | Varies from few to fever and tachycardia associated with toxic megacolon; endoscopic findings are variable: active phase—erythematous, friable, granular mucosa; quiescent phase—granular mucosa with punctate erythema and loss of haustral folds; polyps | Hypoalbuminemia, iron deficiency anemia, fistulas, and stenosis; extraintestinal manifestations affect the liver, eyes, and joints; endoscopic features include aphthous erosions, longitudinal ulcers, cobblestoning, strictures, and fistulas |

| Etiology | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasians and Ashkenazi Jews; 25% of patients have an affected relative | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasian and Ashkenazi Jews; 10% of patients have an affected family member |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Active disease characterized by cryptitis (Fig. 4.9.1) and crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.9.2) often in association with pseudopolyps characterized by heaps of mucosa surrounded by extensive ulceration (Fig. 4.9.3) 2. Increased mucosal chronic inflammation with lymphoid aggregates often prominent at the mucosal–submucosal interface (Fig. 4.9.4); inflammation confined to the mucosa with limited involvement of the submucosa 3. Chronic changes include crypt distortion (Fig. 4.9.5) and background regenerative epithelial changes (Fig. 4.9.6); minimal to no fibrosis in the submucosa 4. Continuous involvement from the rectum extending proximally with more severe changes in distant regions 5. Terminal ileum often uninvolved 6. Loss of submucosal vascular network 7. Rectum always involved 8. Granulomas are not seen | 1. Focal surface epithelial injury (Fig. 4.9.7) characterized by epithelial necrosis with a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate often associated with a lymphoid aggregate (aphthous ulcers) (Fig. 4.9.8) and discrete foci of cryptitis (neutrophils within crypts) (Fig. 4.9.9) and crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.9.10) 2. Transmural inflammation, often more pronounced in the submucosa (Fig. 4.9.11) 3. Chronic changes include crypt distortion (Fig. 4.9.12), basal plasmacytosis (Fig. 4.9.13), and fibrosis, which extends deep into the lamina propria 4. Discontinuous involvement—areas with inflammatory changes adjacent to unaffected areas 5. Terminal ileum often involved 6. Loss of submucosal vascular network 7. Rectal sparing is common 8. Rare poorly formed granulomas with associated chronic inflammation (Fig. 4.9.14) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory drugs including 5-ASA compounds and steroids. Routine surveillance colonoscopy to screen for dysplasia and/or adenocarcinoma is recommended for patients with extensive disease for longer than 8 years. Surgical resection for high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies; surgical resection is generally avoided unless necessary for complications including fissures, fistulas, obstruction |

| Prognosis | Fair; chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to the extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Patients are at increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, and there is a small but measurable risk of early mortality due to toxic colitis as well as other complications | Fair; chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma associated with an 80% mortality rate |

Figure 4.9.1 Intraepithelial neutrophils (cryptitis) in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.9.2 Crypt abscess in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.9.3 Pseudopolyp in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.9.4 Marked increase in chronic inflammation within the lamina propria with a lymphoid aggregate at the mucosal–submucosal interface and background crypt distortion in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.9.5 Crypt distortion in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.9.6 Reactive epithelial changes characterized by enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.9.7 Focal surface erosion in Crohn colitis.

Figure 4.9.8 Aphthous ulcer consisting of a mucosal lymphoid aggregate with an overlying erosion.

Figure 4.9.9 Cryptitis in Crohn disease with background reactive epithelial changes.

Figure 4.9.10 Crypt abscess in Crohn disease.

Figure 4.9.11 Prominent chronic inflammation within the lamina propria of Crohn disease.

Figure 4.9.12 Crypt distortion in Crohn disease.

Figure 4.9.13 Basal plasmacytosis in Crohn disease.

Figure 4.9.14 Poorly formed mucosal granuloma in Crohn disease.

4.10 Sexually transmitted disease–associated proctocolitis vs. Inflammatory bowel disease

| Sexually Transmitted Disease–Associated Proctocolitis | Inflammatory Bowel Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults; males > females | Typically adults (20s–30s and 60s–70s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Usually rectum | Crohn: usually prominent in the proximal colon; rectum is often sparedUC: always involves the rectum and extends proximally |

| Symptoms | Anorectal pain, mucoid and/or bloody discharge, tenesmus, urgency | Crohn: cramping abdominal pain, nonbloody diarrhea, fever, fatigue, weight lossUC: recurrent bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss |

| Signs | Few, if any. A mass may be present at endoscopy, resulting in a clinical impression of neoplasm. | Crohn: hypoalbuminemia, iron deficiency anemia, fistulas, and stenosis; extraintestinal manifestations affect the liver, eyes, and joints; endoscopic features include aphthous erosions, longitudinal ulcers, cobblestoning, strictures, and fistulas.UC: varies from few to fever and tachycardia associated with toxic megacolon; endoscopic findings are variable: active phase—erythematous, friable, and granular mucosa; quiescent phase—granular mucosa with punctate erythema and loss of haustral folds; polyps |

| Etiology | Inflammatory disease associated with various sexually transmitted infections including Neisseria gonorrhoeae (30%), Chlamydia trachomatis (19%), Herpes simplex (2%), and Treponema pallidum (2%) | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasian and Ashkenazi Jews; a subset of patients have an affected relative |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Neisseria gonorrhoeae: most are histologically normal; some show mild increase in neutrophils and lymphocytes with focal cryptitis 2. Chlamydia trachomatis—lymphogranuloma venereum: prominent follicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and plasma cell infiltrate in the mucosa and submucosa; occasional granulomatous inflammation; minimal crypt distortion, only rare crypt abscesses, ulceration, fissuring ulcers, fibrosis, few eosinophils 3. Treponema pallidum: neutrophilic cryptitis (Fig. 4.10.1) with associated ulceration, granulation tissue; marked lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with a predominance of plasma cells within the mucosa and submucosa, which is often angiocentric (Fig. 4.10.2); occasional granulomatous inflammation, but few eosinophils 4. Glandular architecture intact, no crypt distortion 5. Reactive and regenerative atypia can be seen, but no dysplasia | 1. Active disease characterized by cryptitis (Fig. 4.10.4) and crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.10.5) and ulceration 2. Increased chronic inflammation with prominent eosinophils and prominent lymphoid aggregates, which can be transmural (Crohn) or limited to the mucosa (UC) (Fig. 4.10.6) 3. Chronic changes include crypt distortion (Fig. 4.10.7) and fibrosis 4. Rare poorly formed granulomas with associated chronic inflammation (Fig. 4.10.8) 5. Dysplasia can be seen | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Organism-specific antibiotics | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies; surgical resection is generally avoided unless necessary for complications including fissures, fistulas, obstruction |

| Prognosis | Good; most infections resolve with antibiotic therapy | Fair; chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma associated with an 80% mortality rate |

Figure 4.10.1 Prominent lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic infiltrate within the lamina propria with focal cryptitis in syphilis proctitis. Note that although there is basal plasmacytosis, there is no crypt distortion.

Figure 4.10.2 Angiocentric lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the lamina propria in syphilis proctitis.

Figure 4.10.3 Syphilis proctitis. Positive immunohistochemistry for syphilis. Immunolabeling suffers from poor sensitivity and a negative study does not exclude syphilis proctitis.

Figure 4.10.4 Intraepithelial neutrophils in Crohn colitis.

Figure 4.10.5 Crypt abscess and prominent crypt distortion in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.10.6 Marked chronic inflammation within the lamina propria with reactive lymphoid aggregate in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.10.7 Crypt distortion in ulcerative colitis.

Figure 4.10.8 Poorly formed granuloma in Crohn disease.

4.11 Pouchitis vs. Diversion colitis

| Pouchitis | Diversion Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Adults (mean age 40s); no gender predominance | Any age; no gender predominance |

| Location | Distal ileal pouch | Bypassed or excluded segments of bowel, usually rectosigmoid |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, malaise abdominal pain, abdominal cramps, tenesmus, rectal bleeding | Most are asymptomatic; symptoms can include abdominal pain and mucoid or bloody discharge |

| Signs | Fever, abdominal tenderness; radiologic studies may show peri-intestinal inflammation | Few, if any. Radiologic studies, specifically a double-contrast barium enema, can show changes consistent with lymphoid follicular hyperplasia characteristic of the lesion |

| Etiology | Unknown, though some evidence suggests that it is related to impaired butyrate oxidation by the intestinal mucosa; an inflammatory lesion that develops most commonly in patients with ulcerative colitis who undergo an ileal pouch–anal anastomosis procedure involves creating a continent pouch from the distal ileum that can function as a rectum and rarely in patients who undergo the procedure as treatment for a neoplasm. It occurs in approximately 50% of patients with a continent pouch. Risk factors include the diffuse chronic duodenitis, presence of severe colitis that extends into the cecum, early fissuring ulcers, active inflammation of the appendix, and appendiceal ulceration | Unknown; thought to be related to the absence of luminal, short-chain fatty acids, which alters the microbiome of the segment with consequent inflammatory changes. An inflammatory lesion that develops in patients who undergo surgical resection, which is completed with a colostomy rather than reanastomosis of the bowel resulting in a blind segment of bowel with no fecal stream. This is commonly performed in patients with diverticulitis and results in a blind pouch of colon continuous with the anus (Hartmann pouch). Occurs in 50%–100% of all patients with a bypassed segment of bowel |

| Histology | ||

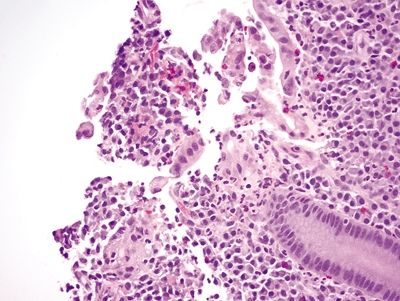

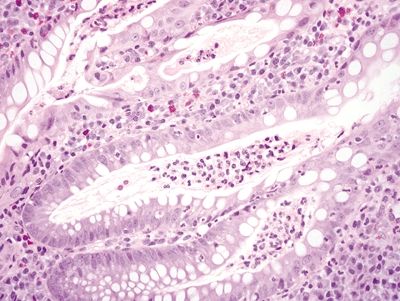

| 1. Acute pouchitis is characterized by prominent infiltration by neutrophils, crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.11.1), and ulceration 2. The changes are seen in association with chronic changes in the background including variable villous atrophy (colonic metaplasia) (Fig. 4.11.2), plasmacytosis (Fig. 4.11.3), reactive changes (Fig. 4.11.4), and crypt distortion (Fig. 4.11.5) | 1. Prominent lymphoid aggregates are characteristic (Fig. 4.11.6) 2. The colitis is mild, but the changes can not only mimic ulcerative colitis including crypt distortion and increased chronic inflammation within the lamina propria (Fig. 4.11.7) but also Crohn disease including aphthous ulcers and cryptitis (Fig. 4.11.8) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | First-line therapy is metronidazole and/or other antibiotics | Surgical reanastomosis to reestablish the continuity of the fecal stream |

| Prognosis | Fair; pouchitis recurs in most patients and has a relapsing–remitting course. The prognosis is related to long-term complications of recurrent disease that include abscesses, fistulae, stenosis, and adenocarcinoma | Good; most cases resolve within 3 months of reanastomosis of the bowel and restoration of the normal fecal stream |

Figure 4.11.1 Pouchitis. Prominent infiltration of neutrophils within the crypt in pouchitis.

Figure 4.11.2 Villous atrophy with colonic metaplasia in pouchitis.

Figure 4.11.3 Prominent plasma cell infiltrate within the lamina propria of pouchitis.

Figure 4.11.4 Reactive epithelial changes with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli seen in a background of cryptitis in pouchitis.

Figure 4.11.5 Crypt distortion in pouchitis.

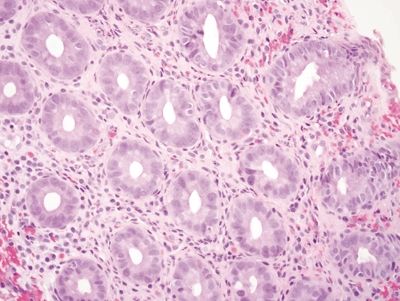

Figure 4.11.6 Prominent mucosal lymphoid aggregate in diversion colitis.

Figure 4.11.7 Crypt distortion and marked chronic inflammation within the lamina propria in diversion colitis.

Figure 4.11.8 Focal cryptitis in diversion colitis.

4.12 Diversion colitis vs. Ulcerative colitis

| Diversion Colitis | Ulcerative Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age; no gender predominance | Typically adults (15–25 and 60s–70s); no gender predominance |

| Location | Bypassed or excluded segments of bowel, usually rectosigmoid | Involves the rectum and extends proximally |

| Symptoms | Most are asymptomatic; symptoms can include abdominal pain and mucoid or bloody discharge | Recurrent bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss |

| Signs | Few, if any. Radiologic studies, specifically a double-contrast barium enema, can show changes consistent with lymphoid follicular hyperplasia characteristic of the lesion | Varies from few to fever and tachycardia associated with toxic megacolon; endoscopic findings are variable: active phase—erythematous, friable, granular mucosa; quiescent phase—granular mucosa with punctate erythema and loss of haustral folds; polyps |

| Etiology | Unknown; thought to be related to the absence of luminal, short-chain fatty acids, which alters the microbiome of the segment with consequent inflammatory changes. An inflammatory lesion that develops in patients who undergo surgical resection, which is completed with a colostomy rather than reanastomosis of the bowel resulting in a blind segment of bowel with no fecal stream. This is commonly performed in patients with diverticulitis and results in a blind pouch of colon continuous with the anus (Hartmann pouch). Occurs in 50%–100% of all patients with a bypassed segment of bowel | Unknown; more prevalent in Caucasians and Ashkenazi Jews; 25% of patients have an affected relative |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Prominent lymphoid aggregates are characteristic usually in a background of marked chronic inflammation 2. The colitis is mild but includes chronic changes such as crypt distortion and increased chronic inflammation within the lamina propria (Figs. 4.12.1 and 4.12.2) 3. Acute inflammation characterized by crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.12.3) and cryptitis (Fig. 4.12.4) can be seen | 1. Active disease characterized by cryptitis (Fig. 4.12.5) and crypt abscesses (Fig. 4.12.6) often in association with pseudopolyps characterized by heaps of mucosa surrounded by extensive ulceration (Fig. 4.12.7) 2. Increased mucosal chronic inflammation with lymphoid aggregates often prominent at the mucosal–submucosal interface (Fig. 4.12.8) 3. Chronic changes include crypt distortion (Fig. 4.12.9), basal plasmacytosis (Fig. 4.12.10), background reactive and regenerative epithelial changes (Fig. 4.12.11) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Surgical reanastomosis to reestablish the continuity of the fecal stream | Mainstay of therapy is symptomatic and anti-inflammatory drugs including 5-ASA compounds and steroids. Routine surveillance colonoscopy to screen for dysplasia and/or adenocarcinoma is recommended for patients with extensive disease for longer than 8 years. Surgical resection for high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma |

| Prognosis | Good; most cases resolve within 3 months of reanastomosis of the bowel and restoration of the normal fecal stream | Fair; chronic incurable disease; prognosis related to the extent and severity of complications and therapy-related side effects. Patients are at increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, and there is a small but measurable risk of early mortality due to toxic colitis as well as other complications |

Figure 4.12.1 Marked chronic inflammation within the lamina propria in diversion colitis.

Figure 4.12.2 Paneth cell metaplasia in diversion colitis.

Figure 4.12.3 Crypt abscess in diversion colitis.