and Andrea Bischoff1

(1)

Pediatric Surgery, Colorectal Center for Children Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Cloacal exstrophy is the most complex, severe, and devastating congenital defect that affects the gastrointestinal tract, the genitourinary tract, the spine and cord, and therefore also potentially the motion of the lower extremities.

From our literature review, we found that prior to 1960 all patients born with this constellation of defects died [1–3]. Peter Rickham in 1960 published a report of four cases, with one survivor [4]. After Rickham, for several years we found multiple isolated reports, small series with overwhelming mortality [5–18].

Until 1964, there had been 52 cases reported in the literature [5]. Until 1991, there were 190 cases reported [6]. The early reports estimated that it affected 1 in 200,000–400,000 pregnancies [5, 19]. More recent reports indicate that it seems to be more common than previously thought [20], most likely affecting 1:100,000–1:50,000 pregnancies.

The list of associated defects is very extensive [21–26] and includes diverse gastrointestinal, genital, vertebral, and urogenital malformations, tethered cord, and other forms of dysraphism and myelomeningocele and intracranial defects.

Regardless of the efficiency of the available treatment modalities and technical advances of the major medical institutions in the world, the final quality of life of these unfortunate patients is still very poor.

Until recently, the quality of life of the patients who survived provoked controversies and serious ethical and unanswered questions [27, 28].

Fortunately, important advances in prenatal diagnoses allow us to detect this defect earlier and earlier in utero, which gives the parents options, in terms of continuation or interruption of pregnancies [28–30].

In more recent years, we saw emerging prestigious centers, with special interest in urogenital malformations. Those centers and their distinguished surgical leaders were able to collect larger series of cases, from which we have learned [31–43]. The contributions of Gearhart et al. [35, 41, 43] have been particularly important.

There is no question in our minds that complex congenital malformation, particularly those affecting different areas of the human body, must be treated in specialized centers, with experts subspecialized in the specific problem. We predict that we will be seeing more and more subspecialized medical centers that will benefit many children.

Cloacal exstrophy affects different anatomic territories that must be discussed and treated separately. From a urinary point of view, these patients have a bladder completely open (extrophic) (Fig. 17.1). What is different about these malformations, when compared to the classic bladder exstrophy, is the fact that these patients actually have two extrophic hemibladders, as can be seen in Fig. 17.1. In between the hemibladders, there is a piece of bowel that can be a colon or small bowel, which can be also prolapsed, creating an appearance that has been called “elephant trunk.” These patients may have, in addition, other urinary problems, such as absent kidney, hydronephrosis, or different kinds of obstruction in the urinary tract.

Fig. 17.1

Cloacal exstrophy. Three examples of the external appearance at birth. (a, b) External appearance. H hemibladders, O omphalocele, B bowel. (c) Cloacal exstrophy. Observe the defective lower extremities

The abdominal wall in these patients is defective, since they have an omphalocele that could be minor or very serious. The pelvis is widely open. The pubic bones are completely separated. The degree of separation and severity of the pelvic malformation is much greater than in classic bladder exstrophies, and therefore, the idea of bringing together the pubic bone as early as possible that is frequently done in bladder exstrophies is not always possible in cases of cloacal exstrophy (Fig. 17.2).

Fig. 17.2

X-ray film showing the wide separation of the pubic bones in a patient with cloacal exstrophy

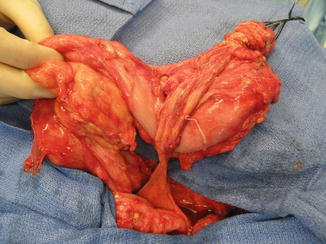

The bowel is also severely affected. These patients are born with no anus. They also have colonic malformations represented by a spectrum that goes from patients that have normal colonic length to patients that have basically absent colon or patients who have a bizarre-looking pouch, as the only representative of the colonic tissue that they have. The pouch may have different sizes and very bizarre and abnormal blood supply (Fig. 17.3). Sometimes the patients have only two little pieces of cecum, with two appendices and a prolapsed ileum. To recognize and identify the length of colon that these patients have is extremely important, because, as we will be discussing later, the possibility of a colonic pull-through will depend very much on the total length of colon that they have. It has been our experience that even when we see sometimes that these patients have a very short piece of colon, the surgeon should not underestimate the potential for growth that those pieces of colon have, and therefore, every single piece of bowel should be preserved.

Fig. 17.3

Intraoperative appearance of the bizarre colonic anatomy, frequently seen in cases of cloacal exstrophy at birth. CO colon, V ileocecal valve, I ileum, B blind end, Ce Cecum

In spite of the fact that these patients would have a less than optimal quality of life in the future, it has been our impression that most of them grow up to become extremely charismatic and intelligent little children. We have been following these patients for many years and have been deeply impressed by their personality and their charisma as well as what they achieve through life.

Female patients are born with two completely separated hemivaginas that may have external orifices located immediately below the hemibladders (Fig. 17.4). Each one of those hemivaginas is directed in opposite directions toward the lateral part of the pelvis. Sometimes, the patients have atresias of the Müllerian structures. They have two widely separated hemiuteri. Usually they have normal ovaries. The two vaginal orifices sometimes are located together at the midline, and sometimes they are widely separated and are located at a very short distance from the location of the ureteral orifices (Fig. 17.4a). Male patients are born with two hemiphalli that are located each one on top of the completely separated pubic prominences (Fig. 17.4b).

Fig. 17.4

Genitalia in patients with cloacal exstrophy. (a) Female. (b) Males

Our series includes 32 cases. This number is obviously not representative of the frequency in the general population, since we work at a referral care center for these kinds of defects. Cloacal exstrophies are another wide spectrum of defects that go from, what we call, covered cloacal exstrophy to a full cloacal exstrophy like those shown in Figs. 17.1 and 17.2.

Fourteen of our cases were classic cloacal exstrophies, 15 were covered cloacal exstrophies, and three were variants of cloacal exstrophies.

From the orthopedic point of view, these patients represent a challenge, because of the wide separation of the pubic bones, more severe than in the bladder exstrophies. In addition, they frequently have spinal problems and luxation of the hips that represent a real challenge for the orthopedic surgeons. It is not unusual to see that these patients have myelomeningocele or severe sacral defects that affect the prognosis of the patient, particularly for the motion of the lower extremities.

An interesting historical fact is related with the designation of gender in male patients born with cloacal exstrophy. For many years, the pediatric surgical as well as the pediatric urologic community considered that it was basically impossible to reconstruct a functional phallus, and therefore, the general agreement was to perform a bilateral orchiectomy, as well as sometimes partial or total resection of the hemiphallus of these patients, and raise them as females, in spite of the fact that they were chromosomally males. Later in life, a vagina was created with the bowel; the patients received a female name, were educated as females, and were expected to have reasonable sexual function as females [31–39, 41].

The long-term follow-up of these patients demonstrated that kind of management was less than optimal. Many of these patients, when they learned that they were actually chromosomally males, became extremely upset because somebody made a critical decision on their behalf, ignoring their own desires. They considered that being a male is much more than just having a phallus to perform sexually, because in addition, if they had gonads, actually they could fertilize and have children, and they had all the other characteristics of a male individual. Also, the long-term observation of the behavior of these patients (chromosomally males raised as females) frequently showed that even when they received a female name and were raised and educated as females, they behaved very much like male individuals. Because of this, our attitude toward these kinds of problems radically changed [44–47]. Nowadays, males are raised as males and females as females. Ambitious urologists are trying to reconstruct the phallus in these patients, to try to make them sexually active in an efficient way. Therefore, the orchiectomies are no longer performed on male patients.

Many patients are born in institutions where different specialty surgical departments (orthopedics, general pediatric surgery, pediatric urology, gynecology) work without a unified, specific plan for the management of these patients. We consider that this is less than desirable. We have created, what we call, a “unified approach” [42, 48]. It is important for all the participants in the management of these patients to previously discuss and create a common philosophy and protocol of management for the benefit of these patients. An example of the lack of coordination and secondary effects that this may have on these patients is a baby that is born with cloacal exstrophy in a hospital where the first contact with the patient is a pediatric urologist, who decides independently to use intestinal tissue to reconstruct the urinary tract. By doing that, sometimes the patient is condemned to a permanent stoma that could have been avoided if more active pediatric surgeons had been present from day one, in the management of these patients. Since the possibility of pull-through or not pull-through in these patients depends very much on the length of bowel that they have and therefore the capacity to form solid stool, it is imperative and extremely important to preserve every single piece of gastrointestinal tract, as part of the gastrointestinal tract, since we have evidence that the bowel grows with time, and even if it looks insignificant in length at the beginning, it may grow more than expected and become crucial, for the patient to be a candidate for colonic pull-through and a successful bowel management in the future.

Another example of the negative consequences of a lack of collaboration could be the reverse, namely, the baby that is seen and treated first by a pediatric surgeon who focuses on the gastrointestinal issues, without paying attention to the extremely important urologic concerns of the patient.

17.1 Neonatal Approach

When the pediatric surgeon is called to see a newborn baby with a cloacal exstrophy, the patient is frequently taken to the operating room, and the pediatric surgeon would be in charge of the closure of the omphalocele and the diversion of the fecal stream.

Some surgeons are very much in favor of trying to approximate the pubic bones as early as possible in life. We agree with the idea; however, the approximation of the pubic bones is more feasible in patients with bladder exstrophy, but not as easy in patients with cloacal exstrophy, in whom the separation of the pubic bones is more severe. In our particular institution, the orthopedic surgeons participate in trying to approximate the pubis, but usually they do not do it in the first few days of life. Therefore, more often the surgeons are called to deal with the omphalocele and the bladder without approximation of the pelvis. This means that the omphalocele can usually be closed, but sometimes it is so large that we can only afford to close it partially (the upper part and not the lowest part of the defect). The bladder is managed by the urology team, and their role consists in trying to close the bladder, to bring together the two hemibladders trying to protect the bladder mucosa, but not with the specific goal of making this patient urinary continent from the beginning. Both the urologist and pediatric surgeon must agree about the main goal which is to separate the gastrointestinal tract from the urothelium, bring together the hemibladders, and close the bladder anteriorly.

The role of the pediatric surgeon is crucial, to be sure that no gastrointestinal tissue is left attached to the urinary tract. The most common error that we have observed, in the neonatal management of these patients, from the pediatric surgical point of view, is for the pediatric surgeon to open a proximal ileostomy and leave the distal bowel (hindgut) attached to the urinary tract. Some pediatric urologists may consider this advantageous, because that creates a reservoir that they plan to use for a future bladder augmentation. However, that bowel absorbs urine, and the babies develop hyperchloremic acidosis that interferes with their growth and development [49]. In addition, the bowel left defunctionalized, attached to the urinary tract, does not grow, as when the bowel is connected to the fecal stream. Every effort should be made by the pediatric surgeon to disconnect every single piece of gastrointestinal tract. Sometimes the patients have two ceca, and those should be placed in continuity, one to the other, in order to try to create a real end colostomy, with no mucous fistula. When the vaginas are opening near one to the other during the same procedure, we try to create a single vaginal orifice by bringing together both openings, but no attempt is made to bring together the entire length of both long hemivaginas.

Many babies born with cloacal exstrophies are referred to us suffering from severe hyperchloremic acidosis and hyponatremia after they underwent the opening of an ileostomy [49]. For them, we designed a procedure that we call “rescue operation,” (Fig. 17.5a, b) consisting in opening the abdomen, closing the ileostomy, separating the gastrointestinal tissue from the urinary tract, reincorporating it into the fecal stream, and opening an end colostomy in the most convenient part of the abdomen, being sure that the bowel opens in an area where it is surrounded by normal skin at 360°. Sometimes, as previously mentioned, the patients are born with two separate portions of colon that look rather insignificant. We must look carefully into the blood supply of these portions of the colon, try to identify which part is proximal and which part is distal and to incorporate them into the fecal stream and again, open an end colostomy. Figure 17.5 shows an example of a rescue operation. We have done twelve of these operations in a patient that received an ileostomy at another institution. The hyperchloremic acidosis improved in 24 h, and the patients eat, grow, and develop very soon after this procedure.

Fig. 17.5

Rescue operations. (a) Diagram showing an ileostomy and the hindgut have left attached to the urinary tract. (b) Diagram showing the anatomy after the operation. The ileostomy was closed, the colon (hindgut) was disconnected from the urinary tract, and an end colostomy was created

Some patients, as previously mentioned, only have a pouch type of colon, which is almost a cystic, very dilated piece of colon, with a very abnormal blood supply (Fig. 17.6). In such cases, we have to observe carefully the blood supply, to be sure that we do not produce ischemia, because every pouch has a different, rather bizarre, unpredictable blood supply. There is always a temptation to resect this pouch, assuming that it will not work, due to a very poor peristalsis and very abnormal anatomy. Yet, we emphasize the importance of preserving every single piece of bowel in these patients, because sometimes the colon is used to create a vagina or to augment the size of the bladder. However, the decision to use gastrointestinal tissue to increase the size of the bladder or to create the vagina should be taken years later at the very end, after the pediatric surgeon has decided whether or not the patient is a candidate for pull-through or a permanent stoma. Even when the patients improve significantly with this end colostomy, sometimes the motility of the piece of colon that the patient has is extremely poor and behaves almost like an aganglionic piece of colon; the patient develops proximal dilatation of the bowel in spite of the fact that there is no stricture. The stasis of stool produces bacterial proliferation and the patients develop secretory diarrhea. For that, the management that we offer to those patients is to teach the mother to do irrigations like we do with Hirschsprung’s disease and give metronidazole by mouth to prevent bacterial overgrowth.

Fig. 17.6

Bowel management through the stoma to determine if the patient is a candidate for a pull-through. (a) Passing a catheter. (b) Contrast in pouch

In the past, we read in many publications that the authors performed permanent ileostomies, or sometimes the paper described the urinary reconstruction, using gastrointestinal tissue, without a mention of what was done in terms of colorectal pull-through [40, 50–55]. Fortunately, we perceive a tendency to change for the good and avoid ileostomies [41–43, 48, 56].

17.2 Pull-Through or “Permanent Stoma”

Some patients obviously have a normal length of colon, and because of that they are candidates for pull-through, since they have the capacity to form solid stool. Even when most of these patients have a very abnormal sacrum and therefore poor functional prognosis, we believe that they are candidates for pull-through, because the quality of life that we offer them, with the implementation of our bowel management program, is much better than the quality of life of patients with an end colostomy. This is something that the patients tell us. Therefore, the only contraindication for a pull-through that we recognize at the present time, in anorectal malformations, is the incapacity to form solid stool. Since this depends very much on the length of the colon, each patient in this spectrum of defects has a different chance to have a pull-through. If the patient has no colon and therefore would never be able to have solid stool, we can anticipate that the patient will remain with an ileostomy for life. On the other hand, if the patient has half or one third of the normal length of colon, we are not sure if the patient will be a candidate for a pull-through. Under those circumstances, we open the end colostomy and watch the patient in terms of growth and development. As mentioned before, small pieces of colon sometimes grow much more than what we expected, provided they are included into the fecal stream. Therefore, every 6 months or every year, the patients come back to our clinic, and we inject water-soluble contrast material through the stoma and monitor the size of the piece of colon. In that way, we can document its growth and development. At the age when the patient is expected to be clean and dry in the underwear (usually 3 years old) and the family and the patient are unhappy about having a stoma, if we are not sure about how good is the water absorption capacity of the colon and whether or not the patient will have a successful bowel management, we offer the family our “bowel management through the stoma” (Fig. 17.6). This means that we teach the mother how to give enemas through the stoma itself. The goal of the management is to have the patient with an empty colostomy bag for 24 h after the enema. If we achieve that, it means that the same result can be achieved in the event of taking that stoma down as a neo-anus. Sometimes those patients require not only the enema, but in addition, they need a constipating diet and the administration of loperamide. If we are successful with this bowel management, the patient and the parents then have an idea of the amount of effort that will be required, in the event of a pull-through, for the patient to stay completely clean in the underwear. Sometimes, the parents find that even when the bowel management through the stoma is successful, the effort to keep the patient clean or the stoma bag clean is too much for the patient, and they prefer not to go for the pull-through. However, the enema, given through the stoma, keeps the stoma bag empty, and parents decide to continue giving the enema through the stoma, because at the age when the children are more active, playing sports is very advantageous for them to have an empty stoma bag, rather than a bag full of stool, with the high risk of leaking during the school activities. Other parents decide to go for the pull-through operation. Figure 17.7 shows an intraoperative view of a pouch colon. It must be tubularized in order to pull it through.