Overview

In chronic kidney disease (CKD), reduced clearance of certain solutes principally excreted by the kidney results in their retention in the body fluids. The solutes are end products of endogenous metabolism as well as exogenous substances (eg, drugs). The most commonly measured indicators of renal failure are blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine. The renal clearance of creatinine (as calculated from a 24-hour urine collection) is often used as a surrogate measure of glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Renal failure may be classified as acute or chronic depending on the rapidity of onset and the subsequent course of azotemia. An analysis of the acute or chronic development of renal failure is important in understanding physiologic adaptations, disease mechanisms, and ultimate therapy. In individual cases, it is often difficult to establish the duration of renal failure. Historical clues such as preceding hypertension or radiologic findings such as small, shrunken kidneys tend to indicate a more chronic process. Acute renal failure may progress to irreversible chronic renal failure. For a discussion of acute renal failure, see Chapter 33.

A new classification has been made by the National Kidney Foundation–Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). This delineates CKD by varying degrees of reduced GFR, either in the presence or absence of structural or functional renal abnormalities (available on the NFK Web site: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm). This has been useful in studies of the progression of CKD, especially in varying drug regimens to reduce the rate of worsening of GFRs.

There are now numerous online calculators that can estimate a person’s GFR (eGFR) based on the creatinine value, one example of which is available through the National Kidney Foundation (http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator.cfm). Although not perfect, these calculations help us to alert patients with subtle renal function impairment in the face of creatinine values within the normal reference ranges.

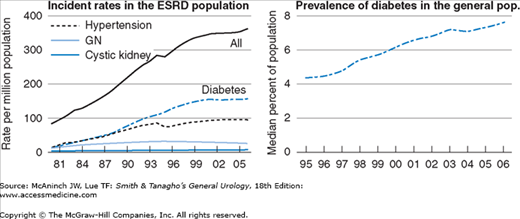

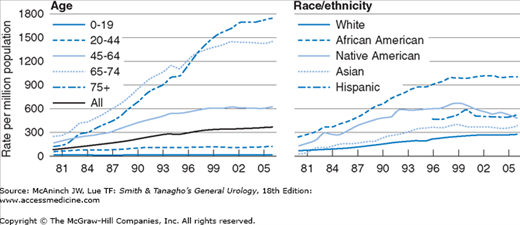

The incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) reached 360 cases per million population in 2006, after a period of relative stability between 2001 and 2005. Almost all of this increase can be explained by the uptake in incidence of diabetic nephropathy over the same period (Figure 35–1). Particularly affected are older patients (75+ years old) and African Americans (3.6 times higher than Caucasians, Figure 35–2). The severity and the rapidity of development of uremia are hard to predict. The use of dialysis and transplantation is expanding rapidly worldwide. As of 2007, more than 340,000 prevalent ESRD patients in the United States are currently treated with hemodialysis, with around 26,000 patients treated with peritoneal dialysis. There are approximately 158,000 patients with a functioning kidney transplant.

There are various causes of progressive renal dysfunction leading to end-stage or terminal renal failure. In the 1800s, Bright described several dying patients who presented with edema, hematuria, and proteinuria. Chemical analyses of sera drew attention to retained nitrogenous compounds and an association was made between this and the clinical findings of uremia. Although the pathologic state of uremia was well described, long-term survival was not achieved until chronic renal dialysis and renal transplantation became available after 1960–1970. Significant improvements in patient survival have been made in the past 50 years.

A variety of disorders are associated with CKD. Either a primary renal process (eg, glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis, congenital hypoplasia) or a secondary one (owing to a systemic process such as diabetes mellitus or lupus erythematosus) may be responsible. Once there is kidney injury, it is now felt that the initially adaptive hyperfiltration to undamaged nephron units produces further stress and injury to remnant kidney tissue, ultimately leading to worsening renal function and urinary abnormalities (ie, proteinuria). The patient will show progression from one stage of CKD severity to the next. Superimposed physiologic alterations secondary to dehydration, infection, obstructive uropathy, or hypertension may put a borderline patient into uncompensated chronic uremia.

With milder CKD, there may be no clinical symptoms. Symptoms such as pruritus, generalized malaise, lassitude, forgetfulness, loss of libido, nausea, and easy fatigability are frequent and nonfocal complaints in moderate to severe CKD. Growth failure is a primary complaint in preadolescent patients. Symptoms of a multisystem disorder (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus) may be present coincidentally. Most patients with CKD have elevated blood pressure secondary to volume overload or from hyperreninemia. However, the blood pressure may be normal or low if patients have marked renal salt-losing tendencies (eg, medullary cystic disease). The pulse and respiratory rates are rapid as manifestations of anemia and metabolic acidosis. Clinical findings of uremic fetor, pericarditis, neurologic findings of asterixis, altered mentation, and peripheral neuropathy are present only with severe, stage V CKD. Palpable kidneys suggest polycystic disease. Ophthalmoscopic examination may show hypertensive or diabetic retinopathy. Alterations involving the cornea/lens have been associated with metabolic disease (eg, Fabry disease, cystinosis, and Alport hereditary nephritis).

In 20% of cases, there is a family history of CKD. A report of antecedent nephritis episodes or a history of previous proteinuria may be elicited. It is important to review drug usage and possible toxic exposures (eg, lead).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree