There is a tremendous literature on cancer, but what we know for sure about it can be printed on a calling card.

—AUGUST BIER

Excluding cancer of the skin, colorectal carcinoma is the second most common malignancy found in most Western countries. In women, lung and breast cancers are more common, whereas in men, lung and prostate cancers are more frequently observed. In 2010, the American Cancer Society estimated that 141,210 new cases would be diagnosed in the United States, and 49,380 deaths would occur.

941 The chance of colorectal carcinoma developing during the life of an infant born in the United States today is approximately 5%.

The incidence of colorectal cancer had been relatively stable for the 40 years before the last two decades, even as death rates were falling. However, the incidence now appears to be decreasing significantly, with an approximately 3% drop observed in the past 10 years alone. This largely reflects increased screening, with adenoma detection and removal.

209,792 Further, the death rate from colorectal cancer has dropped by more than 30% since 1990, owing to earlier detection and better treatment.

941 The trends in cancer incidence, mortality, and patient survival in the United States are derived from the SEER Program (Survey of Epidemiology and End Results) of the National Cancer Institute.

941

▶ SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND OCCUPATION

Some studies have shown a higher death rate for colorectal cancer in more affluent people.

187,752 Colombia, a country with a low incidence, reported a higher rate in this group.

400 However, the vast majority of reports suggest worsened cancer survival in patients with a lower socioeconomic status, typically attributed to patient comorbidities, advanced stage at diagnosis, and diminished access to high-quality care.

1126 Two large studies performed in the United States found that patients of lower socioeconomic status were more likely to have advanced cancer at diagnosis.

143,185 Interestingly, a publication from Ontario demonstrated that significant disparities in survival persist even without a difference in stage at presentation, suggesting other factors are playing a role, such as tumor biology and comorbidities.

106 Elevated body mass index (BMI), obesity, and low physical activity appear to increase the risk of colorectal cancer and may be important confounding variables.

499 Occupation has been investigated as a possible causative factor.

684,752 The relative affluence associated with some occupations appears to be the reason why certain professionals have a higher incidence of colorectal cancer.

▶ ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO

The data regarding alcohol as an independent risk factor for colorectal cancer is conflicting.

175,323,592,781 For example, a prospective study of Japanese men in Hawaii revealed an association between the consumption of alcohol and rectal cancer, attributable to a monthly consumption of beer of 500 oz (15 L) or more.

805 On the other hand, moderate alcohol intake (especially wine) has been found to be protective against the development of distal colorectal cancer.

210 Two meta-analyses on cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer have demonstrated an increased risk among cigarette smokers; the pooled risk estimate ranged from 1.07 to 1.25.

107,575 Current smokers have been shown to have a relative risk of 1.7 for adenomas when compared with nonsmokers. This effect was even more pronounced for advanced or multiple adenomas in a “dose-dependent” relationship, suggesting a direct role in colorectal carcinogenesis.

721 A report from Quebec, Canada evaluated the effects of smoking on the risk of colorectal cancer according to anatomic subsite.

923 A positive association with cigar smoking and rectal cancer was observed. There was no statistically significant association with cigarette smoking, but there was a “positive association” with proximal colon cancer.

Diet

Diet is the epidemiologic area that has received the most attention since the mid-1980s 20 years, especially since Burkitt’s observations (see Biography,

Chapter 27).

133,

134,

135,

136 and

137 He and Painter postulated that a high content of fiber was the primary factor responsible for the low incidence of colorectal cancer in African natives.

777 In essence, their theory states that whatever carcinogen is ingested or produced should be present in a relatively diluted form, and when the transit time is decreased, it is excreted rapidly. Fleiszer and colleagues and Chen and coworkers found that parenteral administration of dimethylhydrazine, a known colon carcinogen, conferred great protection on rats, provided their dietary fiber was increased.

173,303Other studies have demonstrated correlations between colorectal cancer and additional dietary factors. For example, Nigro (see Biography,

Chapter 25) and colleagues demonstrated that cancer in the animal model can be inhibited by an increased fiber intake only when the fat content is relatively low.

742,

743 and

744 They presented a program for possible prevention of colorectal cancer: a 10% reduction in fat consumption, the addition of 25 g of dietary fiber per day, and plant steroids.

742 These substances have been shown to inhibit the cancer that can be induced by carcinogens. One theory holds that inositol hexaphosphate (phytic acid), an abundant plant seed component present in many fiber-rich diets, is one of the specific agents responsible for suppression of colon carcinogenesis.

362The mechanism by which increased dietary fiber achieves protection from the development of large bowel cancer remains speculative. Fiber may provide protection by increasing stool bulk and dilution of putative carcinogens in the colonic lumen, by more rapid transit with diminished exposure to injurious agents, and by fermentation of fiber to short-chain fatty acids.

582 Because fiber is heterogeneous, its mechanism of action within the gut may vary. McIntyre and colleagues studied the effects of three types of dietary fiber in fermentative production of butyrate in the distal colon to ascertain the influence on tumor mass in a rat model of bowel cancer.

663 They observed that the fiber associated with high butyrate concentrations in the distal large bowel is protective against large bowel cancer, whereas soluble fibers that do not raise distal butyrate concentrations are not protective.

Sengupta and coworkers conducted a literature search on the effect of dietary fiber on tumor incidence through the use of the MEDLINE database of all case-control, longitudinal, and randomized, controlled studies published in English between 1988 and 2000, as well as animal model studies in the period, 1986 to 2000.

917 Thirteen of 24 case-control studies demonstrated a protective effect of dietary fiber against colorectal neoplasms; conversely, only 3 of 13 longitudinal studies in various cohorts demonstrated a protective effect of fiber. The animal studies were more impressive; 15 of 19 demonstrated protection against tumor induction when compared with controls. A meta-analysis of 25 prospective studies concluded that a high intake of dietary fiber (in particular, cereal fiber and whole grains) was associated with a modest reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer.

41

Fecal Bile Acids

Population-based studies have demonstrated that a Western diet is associated with high levels of fecal secondary bile acids, primarily deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid, the same trend as has been observed in patients with colon carcinoma.

46,662 Elevated secondary bile acid concentrations exert detrimental effects both on colonic epithelial structure and function.

235 Fecal bile acid concentration is increased by dietary fat and decreased by dietary cereal fiber. Others have shown an unambiguous connection between the fecal bile acid level and the incidence of dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer.

716 Hill and associates determined that the feces of people in Western countries exhibit a high concentration of bile acids when compared with the feces of residents of African and Eastern countries.

444

Cholesterol

Some investigators have demonstrated a strong correlation between colorectal cancer and a high intake of animal fat and protein.

28,455,456 Others opine that the consumption of red meat, or total or saturated fat, has only a weak association with the development of colorectal cancer.

1020 Populations with a high consumption of beef generally have the highest incidence of bowel cancer.

253,254 The epidemiologic evidence is conflicting, but there seems to be an inconsistent relationship of colorectal cancer with respect to fat and sugar consumption, serum cholesterol, and serum β-lipoprotein.

119,633,736,1028,1092 Winawer and colleagues performed a time-trend, case-control study in which serum cholesterol was determined at several intervals before the diagnosis of colon cancer.

1102 They concluded that although individuals in whom colorectal cancer developed had the same levels of serum cholesterol as the general population initially, during the 10 years before the diagnosis of cancer was established, they demonstrated a decline in cholesterol values. This took place in a population of “control” individuals whose serum cholesterol levels tended to increase with age.

A nested case-control study of 520,000 Western Europeans was performed to examine the association between serum levels of total cholesterol and its constituent lipoproteins and colorectal cancer. This included 1,238 incident cases of colorectal cancer during the study period. High concentration of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) was inversely related to the risk of colon cancer (but not rectal cancer); there was no robust association between other blood lipid concentrations and the risk of colorectal cancer.

Bacteria

Bacteria are thought to play a role in the causation of colorectal cancer; their action on ingested fat or metabolites may be a critical factor. Hill and associates demonstrated that people in the United States and Great Britain have a higher colony count of anaerobic flora and a lower count of aerobic bacteria.

444 Others have confirmed this observation.

26 The similarity between the chemical structure of bile salts and the carcinogen, methylcholanthrene, has been observed. It is not unreasonable to hypothesize that the action of bacteria on bile salts may produce a substance capable of inducing malignant degeneration. Burkitt, in fact, postulated that one of the reasons for the preponderance of carcinoma in the distal bowel is the higher concentration of bacteria in this location.

134 Nonpathogenic bacteria play an important role in preserving the function and integrity of the gut’s mucosal barrier. Other bacteria produce toxic metabolites that can cause cell mutations and affect intracellular signal transduction. As such, the intestinal microflora may be a modifiable target for diminishing the risk of colorectal cancer. For example, colorectal cancer patients have higher bacterial counts in the

Bacteroides/

Prevotella group.

929 Probiotics continue to receive attention as potential chemoprotective agents, but there remains little convincing evidence of efficacy to date. Limited studies have suggested a possible increase in colorectal cancer in patients with

Helicobacter pylori infection.

1138

Cholecystectomy

Because of the clinical evidence for an increased quantity of secondary bile acids in the feces of patients with bowel cancer and experimental studies demonstrating that secondary bile acids promote chemical carcinogenesis, cholecystectomy has been implicated as a possible precipitating factor.

1037,1056 This operation increases secondary bile acids in the enterohepatic circulation.

1037 Other reports have failed to confirm a relationship between gallbladder removal and the subsequent development of colorectal cancer.

2,6,95,504 There is, however, some opposing evidence to suggest that more than 10 years following cholecystectomy older women may have an increased risk, especially for right-sided lesions.

632,706 Johansen and coworkers evaluated 40,000 patients with gallstones identified in the Danish Hospital Discharge Register.

495 A borderline significant association was seen between gallstones and cancer of the colon. Jorgensen and Rafaelsen believe that cholecystectomy per se is not responsible for the apparent association, but rather that gallstone disease itself accounts

for the relationship.

501 A meta-analysis of 33 case-control studies showed a pooled relative risk with cholecystectomy of 1.34 for the development of colorectal cancer; the risk for proximal colon cancer was the most significant.

336

Jejunoileal Bypass

With respect to jejunoileal bypass, an operation that in animals promotes the development of chemically induced bowel cancers, there has been no evidence to date to suggest an increased risk in humans,

661 despite profound alterations in transit time, bile salt metabolism, and fecal flora. In a long-term follow-up study (up to 17 years), Sylvan and associates examined these patients postoperatively by means of colonoscopy and biopsy as well as by flow cytometric DNA analysis.

991 These investigators were not able to verify any colorectal malignant transformation.

Ulcer Surgery

An association has been reported between colorectal cancer and prior peptic ulcer surgery, specifically truncal vagotomy.

717 Mullan and colleagues observed increased proportions of chenodeoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid as well as decreased proportions of cholic acid in the duodenal bile of these individuals.

717 They proposed that abnormalities in bile acid metabolism as a consequence of vagotomy could explain the increased risk for the development of colorectal cancer. The cancer risk associated with peptic ulcer surgery was assessed in a cohort of 1,992 surgical patients who were seen in a peptic ulcer clinic in Glasgow, most of whom had undergone vagotomy and a drainage procedure. The risk of colorectal cancer in long-term follow-up was no greater than the general population, irrespective of procedure.

490

▶ ASPIRIN

There is considerable evidence to suggest that regular use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents reduces the risk for the development of colorectal cancer.

1000,1020,1021 Giovannucci and colleagues determined the rates of colorectal cancer among women in the Nurses’ Health Study who reported regular aspirin use, comparing the rates in this group with those of women who stated that they did not use aspirin.

337 They concluded that the risk for colorectal cancer is reduced only after 10 or more years of aspirin use. Thun and coworkers found that dietary consumption of vegetables and grains and regular use of aspirin were the only factors having an independent and statistically significant association with prevention of colon cancer.

1020 An overall analysis of four studies assessing the impact of aspirin in the general population (n

= 69,535) showed no protective effect for the first 10 years of follow-up.

197 However, analysis of the studies involving higher dose aspirin (300 to 1,500 mg/daily) demonstrated a 26% reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancer over a 23-year follow-up period.

197

Estrogen

Most epidemiologic studies have reported an inverse association between postmenopausal hormone (PMH) therapy and colorectal cancer risk.

162 In a report by Paganini-Hill of 7,701 women who were initially free of cancer and used estrogen replacement therapy, there was a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer deaths compared with those individuals who did not take this replacement medication.

775 The impact of hormone replacement therapy may be more pronounced based on the molecular pathway of carcinogenesis. In the Iowa Women’s Health Study, PMH reduced colorectal cancer incidence by 18% overall.

580 The relative risk for microsatellite unstable-low (MSI-L)/MSS tumors was 0.6 when PMH use exceeded 5 years, whereas there was no protection afforded for microsatellite unstable-high (MSI-H) tumors.

580

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease, either ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s colitis, are at increased risk for the development of colorectal cancer; the estimates of this risk has varied considerably in different studies but appears to accrue beginning 8 to 10 years after the onset of symptoms (see

Chapters 29 and

30).

614,682 It seems clear that the duration and extent of disease are key risk factors.

494,552,1053,1109 A Swedish population-based study of 3,000 UC patients found a relative risk of colorectal cancer of 1.7 for proctitis, 2.8 for left-sided disease, and 14.8 for pancolitis.

275 With respect to Crohn’s disease, some reports have been published implicating an association between regional enteritis and small bowel carcinoma.

578,712,875,927 The relationship between granulomatous colitis and large bowel cancer is perhaps less emphasized but appears to be real (see

Chapter 30).

1141

Radiation

There have been considerable differences of opinion about the risk for the development of colorectal cancer following pelvic irradiation. One report demonstrated an increased risk for women who were irradiated for gynecologic cancer.

888 Additional studies are required for an accurate assessment of any relationship, especially in light of the increased application of neoadjuvant therapy.

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppressive therapy, especially following organ transplantation, is associated with an increased risk for the development of malignant tumors, possibly including that of the colon and rectum. Renal transplant patients may have up to twice the risk of colon cancer but do not seem to have an increased risk of rectal cancer. A surveillance colonoscopy program for these individuals is recommended.

Appendectomy

McVay reported an appreciably increased incidence of colorectal carcinoma in patients who had undergone appendectomy.

668 He suggested that the relationship could be explained by immunologic factors. Others have failed to substantiate this relationship.

383,457,467 However, a prior history of appendectomy has been found to be an independent risk factor for decreased survival, worsening the prognosis for those in whom carcinoma of the cecum subsequently developed.

29

Ureterosigmoidostomy

Numerous authors have recognized the relationship between ureterosigmoidostomy and carcinoma of the colon at the site of the ureteral implant into the colon.

394,411,543,616,681,962,981,1042,1082 The incidence of carcinoma ranges from 2% to 15%, with a lag time in the 20-year range.

45 The cause may be related to

bathing of the colonic mucosa by urine, the presence of a carcinogen in the urine, the by-products of the interaction of colonic bacteria, and urine or the effects of the ureter, itself, implanted into the colon. Alterations in the mucus glycoproteins in the surrounding mucosa has been described.

934It is suggested that this type of diversion of the urinary tract be abandoned, especially in young patients with benign disease.

922 Periodic endoscopic evaluation of the bowel is required. Consideration should be given to resecting that area of the colon, with conversion to another diversionaryprocedure.

283,533,962

Congenital Urinary Tract Anomalies

Atwell and coworkers believed they had recognized an association between a family history of congenital anomalies of the urinary tract and the development of colorectal cancer at a young age.

38 Their observations should be taken with caution because the numbers reported were small.

Extracolonic Tumors

With respect to the incidence and risk for the development of a metachronous colorectal cancer following an extracolonic primary tumor, one study demonstrates that a patient with breast cancer has the same risk for a colorectal malignancy as for a second primary tumor in the opposite breast.

11An association between sebaceous gland tumors and internal malignancies has been called the

Muir-Torre syndrome. The incidence of colorectal malignancies is estimated to be almost 50%.

1059 Muir-Torre syndrome appears to be a variant of Lynch syndrome, necessitating genetic evaluation, counseling, and appropriate workup for associated malignancies as described next.

608

Genetic Predisposition

Genetic influences have been known for some time to be an independent risk factor for the development of colorectal cancer. Of all colorectal cancer cases, 2% to 5% can be attributed to known genetic disorders, such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

484 However, another 25% of colorectal cancer patients have at least one first-degree relative with colorectal cancer, without a known, defined genetic predisposition.

1095 These individuals appear to have double the risk of colorectal cancer when compared with the general population.

142This observation could conceivably be a consequence of common environmental exposures, primary genetic factors, the interaction of environment and heredity, or simply of chance.

606 However, in a prospective study, Rozen and colleagues confirmed the relationship of the family history, even when one member harbors a large bowel neoplasm.

866 As a consequence, they and others have advocated a screening program for such family members.

727 Conversely, there is no evidence to suggest a greater frequency of bowel tumors in spouses of colorectal cancer victims. Fuchs and coworkers conducted a prospective study of almost 120,000 patients who had not been previously examined by colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy and who provided data on first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer.

318 The relative risk of cancer in persons with affected first-degree relatives, compared with those without a family history, was 1.72 for one relation and 2.75 for two or more. This increased risk for disease was especially evident among younger individuals (5.37).

Rapid advances in the identification of genetic events that are important in colonic carcinogenesis have been made in the past few years.

13 Specifically inherited abnormalities such as that for familial adenomatous polyposis have been discussed in

Chapter 22. Both acquired and genetic anomalies (

ras gene point mutations; c-

myc gene amplification; allelic deletion at specific sites on chromosomes 5, 17, and 18) seem to be capable of mediating steps in the progression from normal to malignant colonic mucosa (see

Figure 22-15 and

Chapter 22).

13 Chromosomal studies have succeeded in identifying a gene on chromosome 18q that is altered in colorectal cancers.

291 Allelic deletions have been found to occur in more than 70% of such tumors. These are thought to signal the existence of a tumor suppressor gene in the affected region.

291 Specifically, an abnormality of the

p53 tumor suppressor gene, the most commonly mutated gene in human cancer, is thought to be critical to the development of the majority of human tumors.

967 In essence, the presence of the gene through its product (the p53 protein) acts to induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in response to DNA damage.

967

Lynch Syndromes

Excluding the polyposis syndromes, carcinoma of the colon has been reported in cancer families, the so-called cancer family syndrome or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC).

594,601,603,604,806 This hereditary predisposition has been reported to account for at least 3% of colorectal cancer cases worldwide.

409 In a prospective multicenter study from Finland, Mecklin and coworkers investigated family history and other risk factors during a 1-year period for all new patients in whom colorectal cancer was diagnosed.

673 Lynch and colleagues estimate that the risk for development of colorectal cancer is three times greater than that of the general population if one has a first-degree relative with this condition.

606 Familial colorectal cancer, however, requires the presence of the disease in two or more first-degree relatives. Itoh and colleagues noted a sevenfold increased risk for colon cancer.

475 Unfortunately, it has been shown that although family cancer history is commonly obtained during the initial surgical consultation of patients with colorectal cancer, there is a tendency to underestimate the extent and its implications.

871Based on early observations by Warthin,

1068 Lynch and colleagues have defined two clinical variants: Lynch syndrome I or HNPCC and Lynch syndrome II or hereditary site-specific nonpolyposis colonic cancer (HSSCC).

600Lynch syndrome I is characterized by the following features:

Lynch syndrome II is characterized by the same features but, additionally, shows an excess of other adenocarcinomas, particularly involving the endometrium and the ovary.

604,

606,612 Others have added stomach, small bowel, and urinary tract cancers to the spectrum.

602,611,1051 Itoh and coworkers noted that the risk for breast cancer was increased fivefold, and the lifetime risk was estimated at 1 in 3.7 for first-degree relatives of persons with Lynch syndrome II.

475 Even carcinoma of the larynx has been suggested to be associated.

605In the era of molecular genetics, Lynch syndrome is defined in terms of a germ line mutation in a DNA mismatch repair (MMR) gene.

101 The clinical distinctions originally described are largely arbitrary, and the list of associated extracolonic malignancies continues to grow.

608 These include endometrium, ovary, stomach, hepatobiliary tract, pancreas, upper tract urothelial tumors, brain (Turcot’s syndrome), and sebaceous adenomas (Muir-Torre syndrome).

It is useful at this point to define three terms that have entered the literature in this field: Amsterdam criteria, Bethesda guidelines, and microsatellite instability. These criteria are useful in identifying patients who should undergo MSI testing and/or molecular genetic testing to identify germ line mutation in one of the four MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2).

Amsterdam Criteria

In 1991, the following clinical criteria

(Amsterdam criteria) were established to facilitate consistency in research and are often applied in diagnosing HNPCC

1051:

Three or more cases of colorectal cancer in a minimum of two generations

One affected individual a first-degree relative of the others with colorectal cancer

One case of colorectal cancer diagnosed before age 50 years

Exclusion of a diagnosis of familial adenomatous polyposis The criteria have since been modified as follows:

Two cases of colorectal cancer when families are small (one younger than 55 years old)

Two cases of colorectal cancer and one of endometrial cancer or other early-onset cancer

Bethesda Guidelines

The Bethesda guidelines were developed in 1997 from the results of a National Cancer Institute workshop on HNPCC.

854 These guidelines include all of the criteria described in Amsterdam I and Amsterdam II. Because it was believed that the Amsterdam criteria alone led to an underestimation of the true incidence of HNPCC, additional criteria were added. These include histopathologic (signet ring cell, poorly differentiated), morphologic (right-sided), and less selective clinical criteria. Additionally, the guidelines were proposed to assist in the selection of patients whose tumors should be analyzed for microsatellite instability.

1129

Microsatellite Instability

Colorectal cancers demonstrate increased rates of intragenic mutation, characterized by generalized instability of short, tandemly repeated DNA sequences known as microsatellites.

385 A high frequency of microsatellite instability (defined as 40% or more of the microsatellite loci) has been found in most patients with HNPCC. This is because of the inactivation of MMR function by the subsequent loss of the second allele that results in length variations of short sequences in HNPCC colorectal cancers.

1129 This alteration of dinucleotide repeats in microsatellite sequences, MSI or replication error, is used as a diagnostic criterion of MMR deficiency.

755 Early-age-at-onset colorectal cancer has been demonstrated to be correlated with high-frequency microsatellite instability tumor status.

813 It has also been shown to be a marker for predicting development of metachronous colorectal carcinoma after surgery.

937Specific findings of the patients in accordance with Lynch and coworkers were as follows: mean age at the initial colon cancer diagnosis was 44.6 years; of first colon cancers, 72.3% were located in the right side of the colon and only 25.0% were in the sigmoid and rectum; 18.1% of the patients had synchronous colon cancer, with a risk for metachronous lesions at 10 years of 40.0%.

606 Studies have shown the existence of a genetic defect with a population frequency of 19.0% that is transmitted in a mendelian, dominant mode.

266 This defect may predispose the bowel epithelium to the effects of fecal carcinogens.

What clinical clues should lead a physician to suspect the diagnosis of HNPCC? The following have been determined:

Early onset of carcinoma of the colon, especially in the proximal bowel (in the absence of multiple colonic polyps)

Presence of multiple primary cancers (e.g., of the colon, endometrium, ovary)

Having a first-degree relative with early-onset cancers integral to Lynch syndrome II

610

It must be remembered, however, that in the experience of Mecklin and Järvinen, only 40% of patients had a positive family history at the time the tumor was diagnosed.

671 Some have suggested that the flat adenoma, a slightly raised lesion with adenomatous tubules concentrated near the luminal surface, or even a small, flat carcinoma may represent markers for the syndrome (see

Chapter 21).

104,

465,549 When cancers do develop, the incidence of the mucinous type is high.

3,606,674 Svenden and colleagues suggest that young individuals with metachronous colorectal cancer developing after a previous diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma could in fact have HNPCC.

987 The possibility of HNPCC should certainly be considered in adolescents in whom colorectal cancer is diagnosed.

622 Such consideration would inevitably lead the surgeon to make a recommendation concerning the nature of the operation. For example, some have suggested that because there is a high risk for the development of a metachronous colorectal cancer following a limited resection, a total colectomy may be indicated.

1047 Others concur that close relatives of early-onset cases warrant more intensive colonoscopic screening at an earlier age than do relatives of patients in whom disease is diagnosed at an older age.

404,405

Screening

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) established a task force that led to the publication of

Practice Parameters for the identification and testing of patients at risk for dominantly inherited colorectal cancer. The following are the conclusions of that collaborate group

958,959:

Take a family history.

Document a suspicious pedigree. Request medical records to confirm the diagnosis.

Identify criteria for genetic testing (Amsterdam, Bethesda, microsatellite instability in tumors).

Offer surveillance to families not meeting the aforementioned criteria for genetic testing.

Adhere to all protocols for genetic testing, including institutional review board, informed consent, and counseling.

Surveillance

Because the lifetime risk for the development of colorectal cancer approaches 80% in HNPCC, a surveillance program is recommended. In Lynch syndrome I, the surveillance approach is directed to the bowel exclusively. However, with Lynch syndrome II, one must also be aware of the increased risk for the development of extracolonic tumors. Annual colonoscopy is generally believed to be the preferred screening modality for bowel cancer in these individuals, although some believe that this is too frequent; evaluation of the stool for occult blood is unsatisfactory for this purpose.

453,548,606 Because of the increased risk for harboring benign and malignant tumors, colonoscopy is recommended for screening asymptomatic individuals with first-degree relatives having colon cancer, even in the absence of one of the Lynch syndromes.

389,978 Indeed, colonoscopy has superceded prophylactic surgery in those with an inherited mutation.

557 Lynch and associates point out the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences because of failure to diagnose colorectal cancer.

609Green and colleagues performed colonoscopic screening on 61 asymptomatic individuals with an affected first-degree relative who had HNPCC.

372 Neoplasms were found in 15% and malignancies in 3%. Because of the high incidence of multiple lesions, consideration should be given to the performance of subtotal or total colectomy if surgery becomes necessary for colon cancer.

154 A regular, annual endoscopic follow-up of the residual rectum is still necessary, of course.

672 The risk for development of rectal cancer has been estimated to be 3% every 3 years after abdominal colectomy for the first 12 years.

855 There is no doubt that the familial cancer risk associated with early-onset disease outside of the recognized cancer predisposition syndromes is markedly increased.

496With respect to Lynch syndrome II patients, annual pelvic examinations are recommended beginning at age 25, including endometrial aspiration biopsy and ovarian ultrasonography.

606 Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be considered in postmenopausal women and in those who have completed childbearing.

606Lynch and Lynch have made a plea for the establishment of computerized registries, such as have been developed for familial adenomatous polyposis, to transmit information about the diagnosis, surveillance, and management of hereditary colon cancer syndromes.

599,607 Recognizing highrisk families and individuals who would benefit from surveillance should help reduce the incidence of this common malignancy.

112In the Netherlands, families with HNPCC are monitored in an intensive surveillance program. Of the 35 cancers detected while patients were on the program, all but 2 were reported as identified at a local stage.

245

Genetic Testing and Counseling

It is known that HNPCC is caused by germ line mutations in one of four DNA MMR genes:

hMSH2,

hMLH1,

hPMS1, or

hPMS2 (see also

Chapter 22). It is estimated that defects in two of the known MMR genes,

hMSH2 and

hMLH1, account for 90% of mutations found in HNPCC families.

69,815 Although many mutations in these genes have been found in HNPCC kindreds, thereby complying with the so-called Amsterdam criteria, little is known about the involvement of these genes in families not satisfying these criteria but showing clear-cut familial clustering of colorectal cancer and other cancers.

1087 Wijnen and colleagues found

hMSH2 and

hMLH1 mutations in 49% of the kindreds that fully complied with the Amsterdam criteria, whereas a disease-causing mutation could be identified in only 8% of the families in which the criteria were not satisfied fully.

1087 These results imply that there are significant consequences to genetic testing and counseling in the management of colorectal cancer families.

Once the diagnosis has been established, the importance of genetic counseling has been strongly emphasized by Lynch and colleagues and by others.

611,975 It is recommended that all families with suggestive pedigrees should be referred to a geneticist for genetic testing. If the test result is negative for carrying the gene, the family member’s cancer risk drops to that of the general population.

677 Conversely, the lifetime cancer risk for a gene carrier is approximately 90%. However,

individuals need to know the implications and consequences of genetic test results before acquiescing to the testing.

1122Commercial testing is available in the United States through OncorMed.* The company has produced a protocol for testing. People who meet the following inclusion criteria should be tested:

A person with colorectal cancer who has three relatives with colorectal cancer (at least one being a first-degree relative to the other two)

A person with colorectal cancer who has two or more firstor second-degree blood relatives with colorectal cancer

A person with colorectal cancer with onset before 30 years of age

A person with colorectal cancer with onset between 30 and 50 years who has at least one other first- or seconddegree relative with colorectal cancer

A person with colorectal cancer with multiple colon primary tumors

A person with colorectal cancer and another related primary cancer

A relative of an individual with a documented MSH2 or MLH1 mutation

The following people should not be tested:

A person younger than 18 years old

A person with a known diagnosis of ulcerative colitis for 7 or more years, familial adenomatous polyposis/Gardner’s syndrome, hereditary flat adenoma syndrome, Peutz- Jeghers syndrome, familial juvenile polyposis syndrome, or hereditary discrete polyp-carcinoma syndrome

A cognitively impaired person or one unable to provide informed consent

Someone who has a psychological condition precluding testing

▶ AGE AND GENDER

The incidence of carcinoma of the colon and rectum increases with age, but the progression also varies by anatomic site, population, and sex. In our experience, the mean age at diagnosis for men was 63 years, and for women, 62 years.

204 Cook and associates computed the slopes of the logarithm of the incidence against the logarithm of the age from a number of cancer registries and demonstrated that the slopes of the curves for colon and rectal cancer for men were consistently higher than the slopes of curves for women in almost every population.

196 They noted, furthermore, that this variation in male-female difference was greater for colon than for rectal carcinoma.

In women, colorectal cancer ranks third in the United States in number of cancer deaths, 9%. Lung (26%) and breast (15%) are first and second, respectively.

941 The 2011 estimated cancer incidence is third, after breast and lung (30%, 14%, and 9%, respectively).

In men, colorectal cancer (8%) ranks third, after lung (28%) and prostate (11%), for deaths. Prostate cancer is now the single most common cancer (29%); lung is second (14%), and colorectal, third (9%). Men have a preponderance of rectal cancer and a slight excess of cancer of the descending and transverse colon. The incidence of cancer of the ascending colon and cecum is essentially the same for both sexes according to one report,

160 but according to another, women were found to have more right-sided tumors.

980

▶ SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Change in Bowel Habits

Change in bowel habits is the most frequent complaint of patients with colorectal cancer. The change may be as insignificant as that from a bowel movement every other day to one daily. All too often, people place little emphasis on this observation until a profound alteration occurs. Generally, a more distal lesion creates more obvious symptoms than a proximal one. The reasons for this are threefold: first, it is more “difficult” for formed stool in the distal colon to pass through an area of narrowing than for the relatively liquid stool present in the proximal bowel; second, the lumen of the bowel itself is larger proximally than distally; and third, because of the presence of other symptoms (bleeding, pain, discharge), the patient is more likely to pay attention when a distal tumor produces a change in bowel habits.

Bleeding

Bleeding is the second most common symptom of colorectal cancer. It may be overt or occult. The blood may be bright red, purple, mahogany, black, or inapparent. The more distal the location of the lesion, the less altered the blood will be, and the redder it will appear. Although bleeding can represent a relatively early sign of cancer of the bowel, it is often a neglected symptom. Helfand and colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 201 individuals who mentioned rectal bleeding as part of their review of systems evaluation and then determined whether such a complaint merits investigation for significant pathology.

434 They identified 24% with “serious disease,” including benign and malignant neoplasms and inflammatory bowel disease. The authors concluded that physicians should ask all adults about visible rectal bleeding

and should visualize the entire colon in those who manifest such symptoms. Individuals frequently attribute bleeding to hemorrhoids, particularly if they have had prior difficulty with hemorrhoids. For this reason, it is important to treat bleeding hemorrhoids, so that the presence of this symptom succeeds in alerting the patient to seek medical attention.

Conversely, the physician may mistakenly attribute the bleeding to hemorrhoids. Nothing is more tragic than the misdiagnosis of a potentially curable cancer because of inadequate examination or investigation. Too often, patients are managed with suppositories, creams, and laxatives, and only when symptoms become severe enough is proper investigation undertaken.

Mucus

The presence of mucus, either as a discharge (implying a distal lesion) or mixed with the stool, is another symptom; it often accompanies bleeding. The presence of mucus and bleeding should be considered a highly suggestive combination that necessitates bowel investigation.

Pain

Rectal pain is an unlikely presenting symptom of cancer. The most common reasons for anorectal pain are thrombosed hemorrhoids, anal fissure, abscess, and proctalgia fugax. When rectal cancer produces pain, the lesion usually is very distal or very large. Pain may result from infiltration of the sensitive anal canal or from sphincteric invasion. Such invasion may produce tenesmus, a painful urgency to defecate.

Abdominal pain resulting from tumor implies an obstructing or partially obstructing lesion. This pain is usually colicky in nature and may be associated with abdominal distension, nausea, or vomiting. Intestinal obstruction is a presenting complaint in 5% to 15% of individuals with colorectal cancer. Back pain from retroperitoneal extension of a tumor of the ascending or descending colon is an unusual and late sign.

Mass

A palpable or visible abdominal mass in the absence of other signs and symptoms implies a slow-growing, infiltrative process that may be much more amenable to surgical extirpation than might otherwise be anticipated. Such tumors often metastasize quite late in the course of disease.

Weight Loss

Weight loss, in the absence of other symptoms, is a poor prognostic sign. Inanition and loss of strength and appetite suggest metastatic disease, most commonly to the liver. Presentation with symptoms of metastatic disease occurs in approximately 5% of patients with colorectal cancer. Hepatomegaly is a frequent observation, but pulmonary, cerebral, and osseous metastases as isolated findings may reveal an occult colorectal primary on investigation.

Peritonitis

Perforation with peritonitis is an unusual presentation today (except in certain hospitals that serve an indigent population). Differentiating carcinoma from perforated diverticulitis, particularly with a sigmoid lesion, may be extremely difficult (see Surgical Treatment).

“Appendicitis”

Rarely, carcinoma of the cecum can obstruct the lumen of the appendix and cause signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis.

745 An even more uncommon phenomenon is perforation of the appendix from obstructing carcinoma of the more distal bowel.

986 The development of a fecal fistula after appendectomy should lead the physician to suspect an underlying malignancy. Although such presentations are uncommon, any individual older than 50 years old with a presentation of acute appendicitis should be evaluated carefully at the time of surgery for underlying carcinoma.

Inguinal Hernia

It has been thought that inguinal hernia in older men is associated with colorectal carcinoma, especially if the hernia is of relatively short duration.

226,650,812,1013 Because of this observation, some have advised routine colonic examination for all patients before herniorrhaphy. However, Brendel and Kirsh reported no such association.

114 The high incidence of colorectal neoplasms in the general population suggests that the theoretical relationship is more likely to be coincidental. That said, it is known that carcinoma of the colon can present, albeit rarely, as an incarcerated hernia.

451 It is therefore prudent to perform colonoscopic examination prior to undertaking hernia repair in patients experiencing a change in bowel habits or other symptoms suggestive of underlying bowel pathology.

Septicemia

Septicemia from

Streptococcus bovis is associated with gastrointestinal neoplasms, especially colonic neoplasms.

75 Kline and colleagues prospectively studied individuals with sepsis caused by this organism.

527 Eight of 15 who completed gastrointestinal evaluation, including colonoscopy, were found to harbor colon carcinoma. The differential diagnosis of a fever of unknown origin includes colorectal cancer and demands appropriate evaluation.

665 Additionally, fevers of undetermined origin in individuals with known colorectal carcinoma should lead one to investigate the possibility of bacterial endocarditis.

861 Secondary infections of hepatic metastases in an individual with a known primary tumor of the colon are well recognized. However, it is much less appreciated that colonic cancer can be an underlying cause of pyogenic liver abscesses in the absence of metastases. After the usual causes have been excluded, an asymptomatic colon cancer should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

1005 The presence of an organism normally found in the colon should heighten the clinician’s suspicion.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Nonmetastatic cutaneous presentations of colorectal cancer have been reviewed by Rosato and associates.

859 They noted a number of conditions associated with gastrointestinal malignancy, including acanthosis nigricans, dermatomyositis, pemphigoid, and others (see

Chapter 9). Such manifestations are rare, but any disseminated skin condition that is unresponsive to conventional therapy should encourage the physician to consider gastrointestinal investigation.

Cutaneous metastases from colorectal carcinoma are extremely unusual except, of course, in the incision or port site

(see later). Even rarer is the individual who presents with skin lesions as the initial complaint.

225 Certainly, the incidence must be less than 1%. Biopsy will usually clarify any confusion as to the diagnosis.

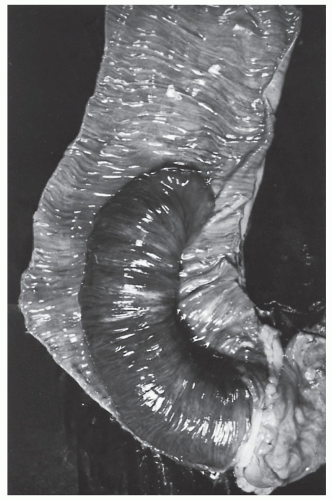

Intussusception

Intussusception in the adult is always a condition that requires surgical treatment. This is in contradistinction to children, for whom medical management (e.g., reduction by barium enema) may result in cure. Patients usually present with signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction.

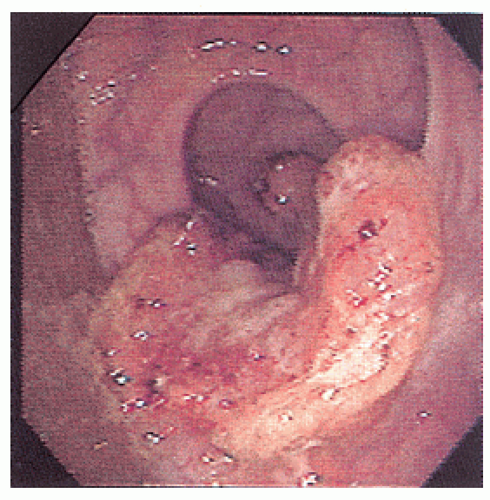

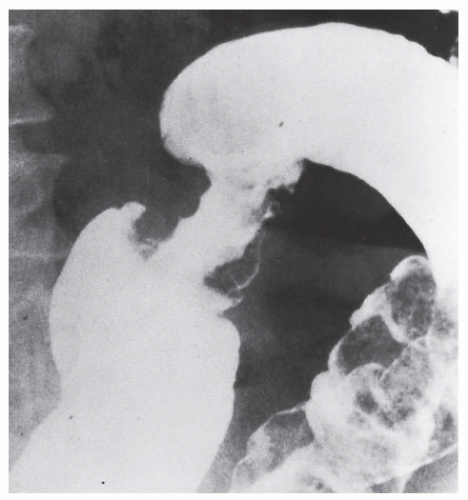

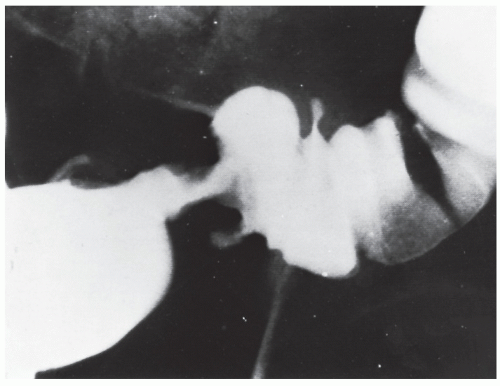

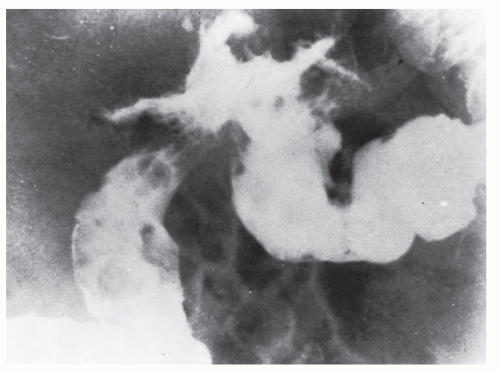

Nagorney and associates reviewed the Mayo Clinic experience with 144 cases of adult intussusception treated at that institution since 1910.

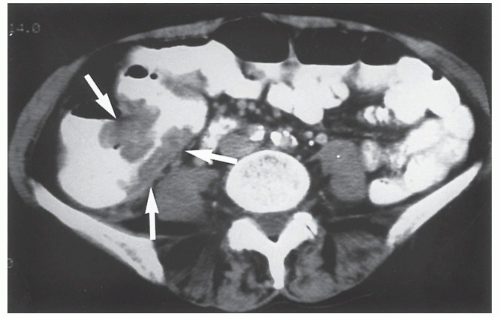

724 Almost 9 in 10 were associated with a definitive pathologic process: malignant neoplasm, benign tumor, metastatic lesion, or Meckel’s diverticulum (

Figures 23-1 and

23-2). Two-thirds of the colonic intussusceptions were associated with primary carcinoma of the colon, whereas only one-third of the intussusceptions of the small intestine were associated with an underlying cancer; most of those malignancies were metastatic. Others have also recognized the association between colonic intussusception and the presence of underlying tumors in the adult.

117,293,734,887,1079 The importance of resection without reduction is discussed later.

Duration of Symptoms

Unfortunately, one continues to be impressed by the long history of symptoms reported by many patients who come to surgery for colorectal cancer. However, those with a short history of symptoms do not have a better prognosis. Individuals with symptoms of less than 5 months’ duration have a higher incidence of resection for cure, but the actual long-term survival has not been shown to be improved.

473,897

▶ PATHOLOGY

By far the most common malignant lesion affecting the colon and rectum is adenocarcinoma. The tumor arises from the glandular epithelium, and it can invade microscopic blood vessels as well as metastasize to distant organs, most commonly the liver. It can spread by way of the lymphatics to regional lymph nodes and ultimately pass into the systemic circulation. The tumor may also extend locally into adjacent organs (e.g., posterior vaginal wall, uterus, bladder, small bowel, stomach, and retroperitoneal structures).

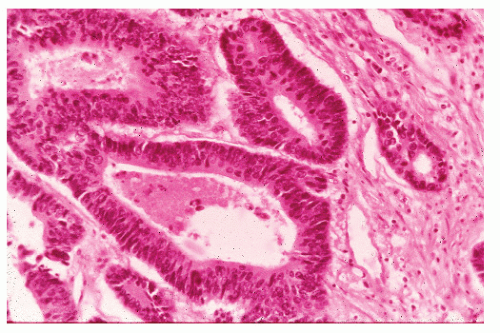

Microscopic Appearance

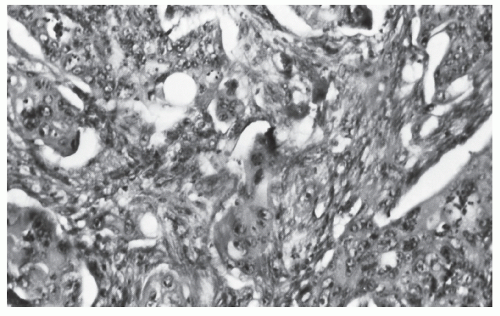

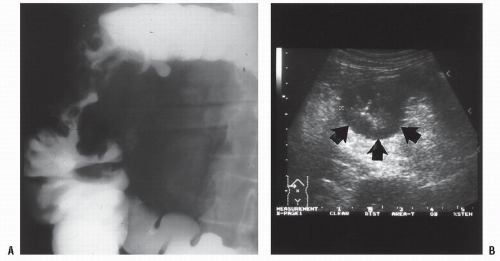

Histologically, the cancer may appear well differentiated (

Figure 23-19), moderately differentiated (

Figure 23-20), or poorly differentiated (

Figure 23-21). The tumor may produce so much mucin that the nucleus is pushed to one side of the cell, creating a signet ring appearance (

Figure 23-22). This last type has been the subject of some debate with respect to its prognostic implications. Minsky has observed that the incidence of this manifestation in patients with colorectal cancer is approximately 17%.

686 He found that colloid carcinoma was not an independent prognostic factor for survival, but believed that it should be reported separately from other histologic patterns in order to achieve a better understanding of its natural history. Generally, the more poorly differentiated tumors are more invasive at the time of diagnosis, and the more invasive the tumor, the poorer the prognosis.

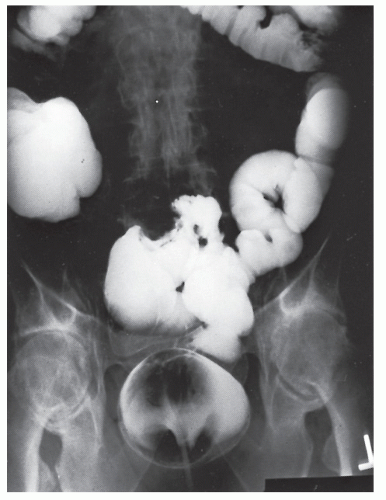

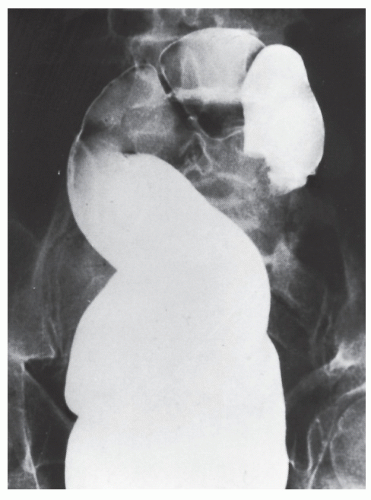

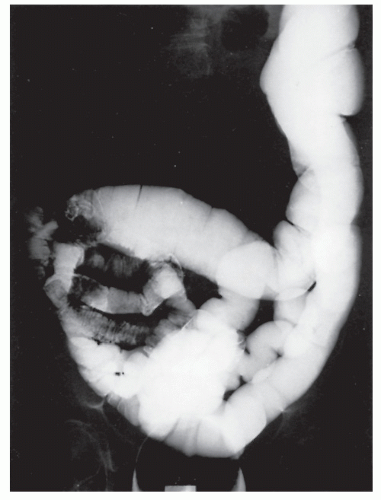

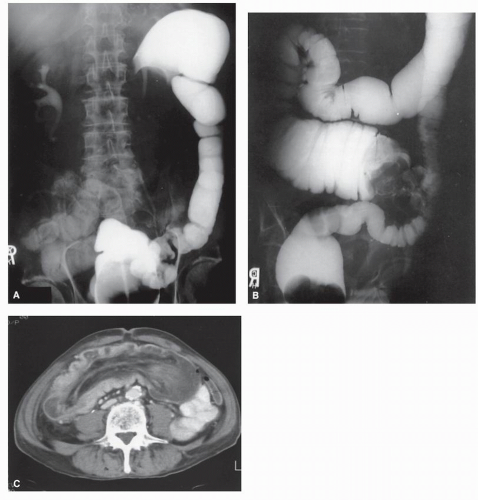

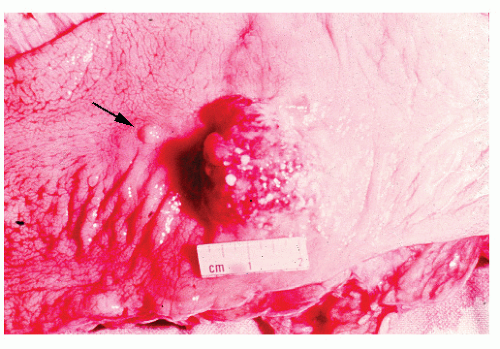

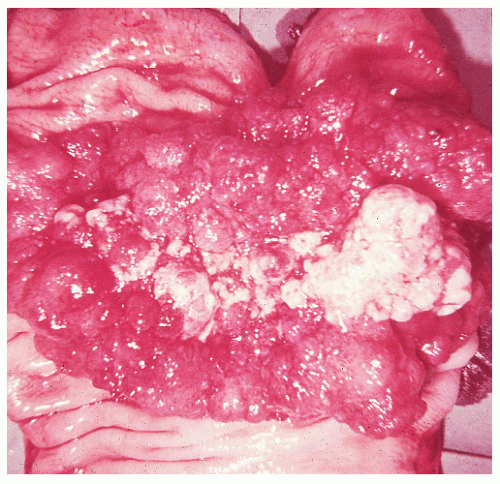

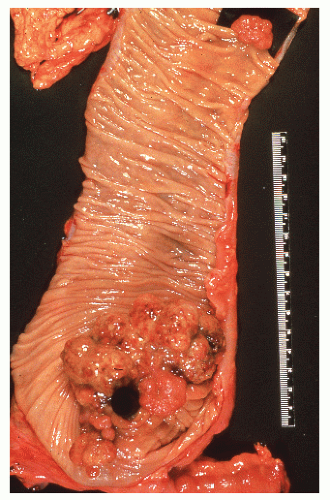

Macroscopic Appearance

In addition to degree of differentiation, tumor morphology— whether polypoid, infiltrative, or ulcerated—has been found to be an important prognostic variable. It, too, should be reported as part of a comprehensive pathologic evaluation of the patient.

972 Macroscopically, the tumor can display a number of forms (

Figures 23-23,

23-24,

23-25,

23-26,

23-27,

23-28,

23-29,

23-30,

23-31 and

23-32).

Factors Affecting Rates of Growth and Spread of Tumor

Carcinomas of the colon and rectum are relatively slowgrowing tumors. Symptoms usually appear early in the development of the disease, and metastases occur relatively late. Tumor growth and spread display considerable variation, depending partly on histologic grade (based on cellular

arrangement and differentiation), increased ameboid action of some cancer cells, enzymes such as hyaluronidase, decreased adhesiveness of the tumor cells, size of the lesion at the primary site, and length of time the tumor has been present.

379,990 Daneker and colleagues showed the interaction of the tumor with the basement membrane to be an important factor in predicting spread.

222 They noted that in general, more poorly differentiated cancers tend to adhere and therefore to invade much more readily. Additional variables include location of the tumor, indeterminate host

factors, manipulation at surgery, and the age and sex of the person.

40,189,270,440,889Histochemical studies assess those factors that contribute to tumor growth and spread. These include changes in sialomucin in the distal resection margin and the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin.

229,938 For example, Dawson and colleagues showed that sialomucin adjacent to a primary colorectal cancer provides a crude assessment of tumor invasiveness and therefore the risk for local recurrence.

228 Ideally, as more information is developed about prognostic factors, more meaningful recommendations with respect to supplementary therapy will be made.

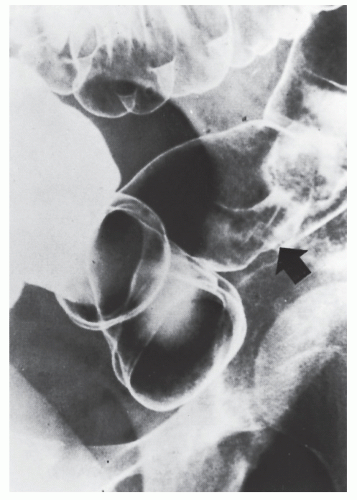

The first opportunity to measure the growth of colonic cancer at its site of origin was reported in 1961 by Spratt and Ackerman.

955 In this study, nine air-contrast enemas were performed during a period of 7.5 years.

954 Radiographic measurements of the tumor were taken, and by appropriate plotting on a graph, the growth curve was shown to conform to an exponential increase in volume. The tumor was calculated to have a doubling time of 636.5 days. When desquamation from the surface was taken into account, it was postulated that a net increase of only one cell per 1,000 cells per day was adequate to account for the observed rate of growth. Another study demonstrated the mean doubling time of tumor volume to be only 130 days.

103 The authors believed that this high rate of growth could be attributed to the large

size of the tumors and therefore their greater likelihood of being malignant at the initial examination.

Doubling time of pulmonary metastases from colon and rectal carcinomas has been calculated radiographically and found to be 109 days.

953 Metastatic tumors increase their cellular complement six times faster than primary cancers.

954 It is theorized that the absence of desquamation in the metastatic site accounts for this observed difference.

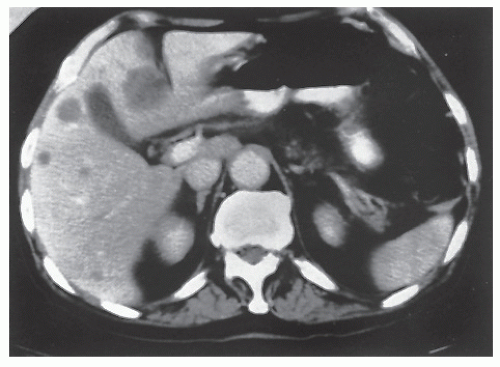

Finlay and colleagues studied the growth rate of hepatic metastases by means of serial CT.

299 They discovered that the mean doubling time for obvious metastases (those discovered at the time of laparotomy) was 155 days, compared with 86 days for occult metastases. By means of extrapolation, the authors concluded that the mean age of the former lesions was 3.7 years, and the latter was 2.3 years.

The metastatic behavior of neoplasms varies. According to Spratt, examination of the cancer-host interface is helpful in determining the behavioral pattern of the tumor.

953 One that is less likely to metastasize exhibits a well- circumscribed, intact margin. The tumor that is more likely to metastasize to lymph nodes has a loose or infiltrating margin with little inflammatory reaction. Sacchi and coworkers looked at the border between normal tissue and tumor in colorectal cancer and opined that it is the mast cell, probably influenced by the inflammatory infiltrate and/or colorectal cancer cells themselves, which destroy lymphatic vessels, thereby preventing spread into the lymphatic system.

874Some investigators have suggested that the concentration of circulating C-reactive protein may play a role in predicting recurrence and survival in colorectal cancer. McMillan and colleagues studied the presence of a systemic inflammatory response as measured by circulating C-reactive protein in 174 patients who were believed to have undergone a curative resection.

666 C-reactive protein concentration was found to be an independent predictor for survival—that is, the presence of elevated concentrations predicts a poor outcome.

Delay in Diagnosis: Legal Implication

The one article by Spratt and Ackerman has been responsible for more confusion, misinterpretation, and misrepresentation in the sphere of medical litigation with respect to the accusation of delay in diagnosis than all other variables combined. A question asked by attorneys in medicolegal actions is when an earlier diagnosis will make a difference with respect to prognosis (see

Chapter 34). Clearly, the issue of tumor doubling time does not provide the answer. In an unofficial poll of the Chicago Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (1997), all but 2 of the more than 50 surgeons who were in attendance responded “6 months.” For the record, the concept of cancer doubling time is without merit in considering the likelihood of survival and its applicability to earlier diagnosis and prognosis in the individual patient.

Staging and Prognosis—History and Current Status

Classifications

The importance of tumor invasion and its prognostic implications was postulated by Dukes in 1930 and was subsequently revised by him in 1932.

262,263 This has come to be known as Dukes’ classification (not Duke’s). The classification was originally directed toward rectal cancer (

Table 23-1). After performing numerous meticulous dissections of resected specimens to identify metastases to lymph nodes, Dukes

further modified his classification in 1944.

264 Those tumors with lymph node involvement but with a negative node at the ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery he called C

1. Lesions classified as C

2 had metastases to the node at the level of the ligature (

Table 23-2). The addition of the D category has been generally accepted as representative of tumor spread beyond the reach of potential surgical cure but was not included in his classification (

Table 23-3).

Others have introduced their own classifications, expanding and subdividing Dukes’ system and broadening it to include colon cancer and disseminated metastases; degree of differentiation; tumor morphology; and histogram pattern, among others.

36,295,523,785,1036,1140 Jass and colleagues suggested a classification based on prognosis

485:

Excellent prognosis

Good

Fair

Poor

A scoring system was developed based on several factors that appear to influence survival—number of lymph nodes with metastatic tumor, character of the invasive margin, presence of peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration, and local spread. Most observers believe that the classification of Dukes is of greater prognostic value and more reproducible than that of Jass.

233Figure 23-33 illustrates other staging systems. In theory, the more one “substages,” the greater the refinement potential to predict tumor behavior, and therefore to gain more information about the possible outcome.

738 There is even a Japanese classification that subdivides vertical invasion of the submucosa into Sm1 (upper third of the submucosa), Sm2 (middle third), and Sm3 (invasion near the “inner surface of the muscularis propria”). The question, however, is whether this is really important, especially in the absence of adjuvant therapy specific to disease-invasion subsets. The TNM system has become the most popular classification in use in the United States and indeed in the world (

Tumor-

Node-

Metastasis). The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) seventh edition staging system is shown in

Table 23-4.

Fisher and colleagues compared the relative prognostic value of the Dukes, Astler-Coller, and TNM staging systems in 745 pathologically evaluable individuals with rectal cancer.

301 They concluded that the Dukes method was the simplest and most consistent algorithm related to prognosis. They observed, however, that the Astler-Coller C1 and C2 designations were a uniquely valuable contribution to prognostic discrimination. The same is probably true of the TNM classification.

Goligher’s Commentary

John Cedric Goligher (see Biography,

Chapter 21) wrote that the various classifications proposed can create only confusion and mislead the reader interpreting the surgical results from one institution to another. He observed,

It is the unalienable right of every pathologist and surgeon to evolve his own system for categorizing the extent of spread of cancers of the colon and rectum … [but] I suggest that it would be more useful to restrain his urge to classify and accept Dukes’ categorization exactly as it was defined by him.

351

Despite this suggestion, since 1991 the Council of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons endorsed the TNM staging classification. More’s the pity, for I believe that the clinicopathologic classification of Dukes fulfills all reasonable criteria for prognostication. Other studies comparing the various staging classifications concur with this conclusion.

166,233,300,301,581,728 Sadly, the plea for romance and historical precedent has inevitably fallen on deaf ears—the TNM classification has become the benchmark that we all must accept and adopt.

Lymphatic Invasion

The importance of lymph node involvement by tumor has been well established through providing important prognostic

information.

331,335,368,382 It seems reasonable, therefore, that if one were to use special clearing techniques, a greater number of lymph nodes will be identified, thereby improving the ability to prognosticate.

382,468,796 Koren and colleagues proposed the use of a lymph node-revealing solution composed of various traditional fixatives and fatty solvents to clear the mesentery and identify more lymph nodes.

535 In 30 problematic cases, in which an unsatisfactory number of lymph nodes were found by the traditional method, this approach resulted in upstaging a number of tumors from N0 to N1. The number of positive nodes has been shown in one study to be a more accurate predictor of survival than depth of tumor penetration.

1118 Very few pathology laboratories employ a clearing technique, but if all pathologists vigorously pursued lymph node identification, a greater consistency in reporting the results of treatment would be achieved.

Tsakraklides and colleagues evaluated the histologic morphology of lymph nodes in an attempt to improve prognostic ability.

1035 They found a higher rate of survival (which was not statistically significant) in patients whose nodes showed germinal center predominance compared with those whose nodes showed lymphocyte predominance, the “unstimulated pattern.”

Cutait and coworkers demonstrated that by using immunoperoxidase staining of CEA and cytokeratins of lymph nodes previously considered free of disease, restaging of 22 nodes became necessary.

217 However, follow-up at 5 years failed to show any statistically significant difference in survival.

Numerous studies have appeared in the literature in recent years attesting to the impressive survival advantage for patients with more lymph nodes identified in their surgical specimens.

171,499,574 The implication is that low node counts are markers for inadequate surgical technique and/or suboptimal pathologic examination, often falsely “downstaging” patients who harbor undetected lymph node metastases. The need to find 12 or more nodes has even been specified as a quality indicator for colon cancer surgery. However, it should be clear that this is a marked oversimplification of the relationship between lymph node counts and prognosis because studies using node clearing techniques to identify dozens of additional nodes have shown only a minimal frequency of upstaging.

123,906 Indeed, even when surgical and pathologic factors are controlled for, the number of lymph nodes identified in the specimen continues to be strongly associated with improved prognosis.

705 It may be that a greater number of nodes is a surrogate for a more immunogenic tumor or a more immunocompetent host.

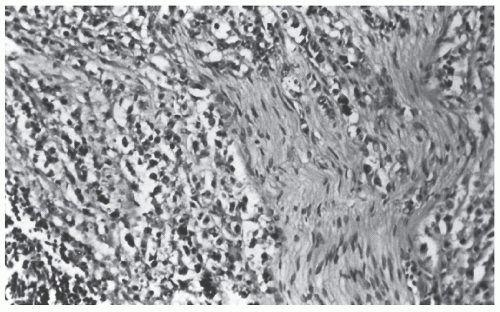

Blood Vessel Invasion

Compared with lymph node involvement, the importance of blood vessel invasion (

Figure 23-34) has been emphasized to a much lesser extent.

115,122,302 However, the prognostic implication of blood vessel invasion has been well established,

203,936 a fact that has stimulated different approaches to the technique of surgical removal of the tumor (see later).

53,302,882,1036 It should be axiomatic that the pathologist seek to identify and report invasion of blood vessels with the same concern applied to identifying involvement of lymph nodes.

Neural Invasion

As with blood vessel invasion, neural invasion has prognostic import—that is, the presence of perineural invasion implies a more ominous prognosis than if such invasion were not present.

DNA Content or DNA Ploidy

Some studies have suggested that tumor DNA content, as determined by flow cytometry, can provide valuable information about the biologic behavior of neoplastic cells and is therefore an important prognostic factor in determining survival.

27,51,531,908,1093 Aneuploid (nondiploid) tumors contain a population of cells that exhibit a DNA content distinctly different from the DNA noted in “normal” (diploid) malignant cells. For example, Scott and colleagues reported that DNA nondiploid rectal carcinomas were associated with a statistically significant increased incidence of vascular invasion, tumor fibrosis, and advanced Dukes’ stage.

907 In another study from the same unit, these cancers also were associated with a significantly poorer prognosis in patients with unresectable disease.

908 Kokal and colleagues demonstrated that in comparison with diploid tumors, tumors with abnormal DNA content tended to be less well differentiated, to invade the serosa or extend beyond, and to have lymph node metastases.

532 It should be remembered, however, that tumor cell DNA content, although it can be an independent prognostic factor, is not as accurate as Dukes’ classification in this respect.

108,433,902 Deans and associates performed flow cytometry on 312 patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum and found by univariate survival analysis that no flow cytometric variable was statistically significantly related to survival.

234 They concluded that Dukes’ stage, patient age, and tumor differentiation are the variables most closely related to survival, and that conventional histologic variables remain the best predictors of prognosis for this condition.

234 Others believe, however, that tumor DNA content

is the single most important prognostic factor among all the clinical and pathologic variables available.

232,532,533 Although there may be some controversy in this respect, there is no disagreement that nondiploid lesions are generally associated with a greater level of invasion and therefore a more advanced Dukes’ stage.

Oncogene Analysis

Rowley and colleagues compared DNA ploidy and nuclearexpressed p62

c-myc oncogene in the prognosis of colorectal cancer.

863 As discussed earlier, oncogenes exist in the normal human genome as proto-oncogenes but may be activated by various means in tumors, including overexpression and mutation (see also

Chapter 22).

863 The authors could not suggest a replacement for Dukes’ staging system for prognostication but observed that the combination of ploidy status and oncogene expression predicted survival better than ploidy alone.

Nucleolar Organizer Regions

Nucleolar organizer regions are loops of ribosomal DNA in nuclei that direct ribosome and protein formation.

708 Moran and colleagues studied the prognostic implication of these regions, as well as ploidy, in individuals with advanced colorectal cancer.

708 They concluded that nucleolar organizer regions are the most important individual variable for predicting survival, whereas ploidy values are equivalent to histologic differentiation.

Nuclear Morphology

Mitmaker and coworkers studied nuclear shape as a possible factor in determining prognosis.

693 The nuclear shape factor was defined as the degree of circularity of the nucleus, with a perfect circle recorded as 1.0. A shape value greater than 0.84 was associated with a poor outcome and indeed was the most significant predictor of survival even when corrections were made for sex, age, histologic grade, and Dukes’ classification.

Doppler Perfusion Index

Leen and associates assessed the relative value of Dukes’ staging and the Doppler perfusion index (DPI) as prognostic indices in individuals who underwent apparently curative surgery for colorectal cancer.

561 This index, the ratio of hepatic arterial to total liver blood flow, was measured before resection by means of duplex/color Doppler sonography. The authors observed that the DPI identified two groups of individuals—78% of those with an abnormally elevated DPI value had recurrent disease or died, whereas 97% of those with a normal DPI value survived. The implications concerning the suitability for adjuvant therapy following apparent curative resection are clear.

Tumor Budding

Tumor “budding” refers to the presence of microscopic clusters of undifferentiated cancer cells ahead of the invasive front of the lesion. This has been believed to have prognostic significance with respect to cure rates following resection for colon and rectal cancer. Hase and colleagues analyzed all surgical specimens for this phenomenon in 663 patients who underwent curative resection.

427 The presence of severe budding was associated with a poorer prognosis and paralleled a ‘more invasive Dukes’ classification.

Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen Expression

Cellular proliferative activity has been shown to be a useful indicator of biologic aggressiveness in colorectal carcinoma. Choi and associates investigated the correlation between proliferative activity and malignancy potential in colorectal cancers to determine whether the proliferative index of cancer cells has prognostic significance.

176 Using immunohistochemical methods involving a monoclonal antibody to proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), they obtained 86 pathologic sections and compared PCNA with conventional clinicopathologic factors as well as other prognostic parameters. The authors determined that PCNA at the invasive tumor margin was a valuable predictor for determining those individuals with a higher potential for metastasis or recurrence.

176

Anatomic Distribution

Numerous reports have demonstrated a change in the distribution of colorectal carcinoma.

1,148,211,356,374,710,943 It had long been thought that 75% of colorectal cancers were within the range of the rigid proctosigmoidoscope. More recent data suggest that the figure should be closer to 60%.

Cady and associates reviewed almost 6,000 resected specimens of the large bowel that had been removed during a 40-year period (1928 to 1967).

148 During this time, the incidence of cancer of the right side of the colon increased from 7% to 22%, and the incidence of rectosigmoid, sigmoid, and rectal carcinomas fell from 80% to 62%. These changes represented statistically significant differences. A trend to smaller tumors was also evident, with less frequent lymph node involvement of the distal lesions, possibly reflecting an improvement in early detection. Beart and colleagues reviewed the Mayo Clinic experience by studying the new cases diagnosed among residents of Rochester, Minnesota, between 1940 and 1979.

60 They found an increase in the incidence of proximal lesions (from 15.1/100,000 person-years in 1940 to 1959 to 17.3/100,000 in 1960 to 1979). This coincided with a fall in distal lesions (from 35.5/100,000 person-years to 28.2/100,000 person-years). In a 2002 report from the Netherlands, the incidence of colorectal cancer has almost doubled from 1981 to 1996, whereas the proportion of proximal cancers increased from 25% to 37%.

678 Gonzalez and colleagues found that increased age, female gender, Black non-Hispanic race, and the presence of comorbid illnesses were factors associated with a greater likelihood of developing colorectal cancer in a proximal location.

356 In a Veterans Administration study, black race was likewise shown to be associated with a higher incidence of right-sided tumors than that of whites.

211A possible explanation for the observed increase in the proportion of more proximal colon cancers is the “search and destroy” concept for the management of colorectal polyps. By clearing the rectum through electrocoagulation, biopsy excision, and snare excision, one essentially prevents the subsequent development of a distal malignancy. Another obvious implication is the limitation of proctoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy as a screening tool.

▶ SURGICAL TREATMENT Historical Perspective

Resection of the bowel with intestinal anastomosis is a relatively recent operation. In 1818, Zang declared that “every

intestinal suture is a mighty procedure in a highly vulnerable organ, and therefore a dangerous, yes, a very dangerous undertaking.”

314 Exteriorization was the method of treatment for intestinal disease and injury, a technique that had remained essentially unchanged for more than two millennia.

Reybard of Lyons in 1833 was the first to perform a successful resection of the sigmoid colon; for this he was criticized by the Paris Academy of Medicine.

221,843 Colostomy was advocated as a palliative procedure as early as 1839. Before this time, an occasional obstructing carcinoma of the colon was relieved by the spontaneous formation of a fecal fistula, when it was relieved at all. Before 1889, the mortality rate for colonic resection was 60%, but this figure had been reduced to 37% by 1900.

709 Because of the high mortality for intra-abdominal resection and anastomosis, the staged extraperitoneal operations of Paul,

784 von Mikulicz,

683 and Bloch

97 (exteriorization-resection) were usually employed.

The initial attempts to coapt ends of intestine involved insertion of various objects into the lumina of the cut ends of the bowel, with or without the addition of sutures. These procedures involved the use of a reed pipe, goose trachea, cardboard smeared with sweet oil, a cylinder

of fish glue, a wax ring, and a silver ring, to name a few.

314,545 Balfour suggested the use of a tube stent.

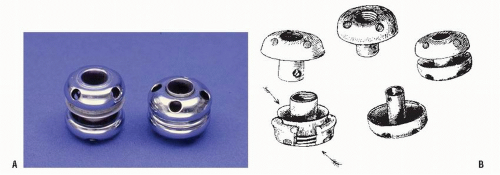

49 Probably the most famous internal stent was the Murphy “button” (

Figure 23-35).

720 Introduced in 1892, it quickly became the primary method of anastomosing bowel.

Until the 19th century, most surgeons regarded wounds of the intestine as a

noli me tangere (do not touch), believing that nature would be more successful in the healing process than any artificial attempt to effect closure.

918 Travers (1812) is believed to be the pioneer in the use of sutures to perform intestinal anastomoses.

1031 Lembert (1826) is eponymously associated with a type of intestinal suturing that produced a serosa-to-serosa apposition.

566 As he was with so many other operative innovations, Billroth was also one of the leaders of intestinal anastomotic surgery. In 1887, Halsted reported an experimental study demonstrating the submucosa to be the primary layer responsible for a safe and secure anastomosis and emphasized the importance of inversion of the intestinal suture line.

406 This was confirmed in a subsequent report.

407 Later, Connell described his continuous inverting suture.

194 Allis simplified the technique of suturing intestine when he introduced his tenaculum forceps in 1901.

17 For an excellent, comprehensive review of the history and evolution of the diverse anastomotic techniques developed prior to the 20th century, one should read Senn’s classic article on the subject.

918 A wonderful, contemporary perspective can be gleaned from the article by Steichen and Ravitch.

968In the 20th century, resection of the colon and primary anastomosis did not become generally used until the antibiotic era. In fact, in many centers, resection of the sigmoid colon was not attempted without a diversionary colostomy until the 1950s. Dixon, among others, is regarded as one of the advocates of primary anastomosis without colostomy.

247 Numerous articles have been written that address the means to avoid fecal contamination with bowel resection (closed anastomosis with noncrushing clamps; rubber-shod clamps) and to avoid inverting too much tissue (e.g., the Gambee suture).

322 To complicate the issue further, Getzen and associates advocated the use of eversion, concluding that it produces a more secure anastomosis than inversion.

329 Although this contention was supported by some studies,

152,408,431,587 other reports refuted the observation.

355,873 The hand-sewn eversion technique is in disfavor and should never be used. Suturing has historically been the true surgeons’ art form. But today, surgeons-in-training have only a limited opportunity to sew. Maintaining this skill, however, is critically important because there are times that one cannot employ a stapling technique.

de Petz was not the first person to describe a stapling device, but he is generally credited with having produced the initial practical instrument, employing it for gastrectomy.

244 Stapling techniques, however, were developed as early as 1908 by Hültl and Fischer.

969 However, the real credit must be given to the Russians for producing the contemporary

stapling instruments.

314 They, as well as others, performed stapled anastomoses that were sometimes everting and sometimes inverting.

23,823,824 Ultimately, the Russian SPTU gun was described. It produced an inverting end-to-end anastomosis by means of a circular row of staples placed within the lumen of the bowel. The United States Surgical Corporation (Tyco; Covidien, Inc., Norwalk, CT) was the initial developer of stapling instruments in this country, and other American companies produced further modifications. Reports of their successful application are myriad.

352,354,429,825,836 The latest major innovations involve the application to laparoscopic bowel surgery (see

Chapter 19).

Preoperative Preparation

For elective colon resection in the United States, patients are usually admitted to the hospital the day of surgery, depending on the likelihood of achieving an adequate bowel cleansing if the preparation is undertaken on an outpatient basis. A more prolonged hospitalization to prepare the bowel or to perform preoperative testing is generally not believed to be necessary and, in the era of cost containment, can rarely be justified to insurance carriers, even when the indications are reasonable.