and Andrea Bischoff1

(1)

Pediatric Surgery, Colorectal Center for Children Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary material is available in the online version of this chapter at 10.1007/978-3-319-14989-9_20.

20.1 Introduction

We use the term “bowel management for the treatment of fecal incontinence” to refer to a program implemented at our institution which is designed to keep patients who suffer from fecal incontinence artificially clean in the underwear [1–3]. The management basically consists of the administration of an individually designed enema that is given once a day, which allows the patient to remain completely clean in the underwear for 24 h. In a number of cases, the program includes the medical manipulation of the colonic motility with a specific diet and/or medication such as loperamide.1

Enemas have been used for the management of fecal incontinence for many years with variable results [4–12]. When the patients come to our clinic and their parents learn about what our bowel management program is all about, it is not unusual for us to perceive their disappointment. They frequently explain to us that they expected a more sophisticated management of fecal incontinence; in fact, they frequently say that their child previously received enemas that resulted in no improvement. Some even say that enemas actually make their son or daughter worse in terms of bowel control. That parent’s reaction is understandable. The bowel management program that we implement in our clinic includes therapeutic elements (enemas, constipating diet, and medications to slow down the colonic motility) that have been widely used in the past in the management of fecal incontinence. However, we like to say that we use the same therapeutic elements, but with a specific, different rationale that allows us to have a high degree of success. We explain this to the parents and ask them for patience and tolerance, so we can demonstrate that the same therapeutic elements (enemas, diet, and medication) when used following a systematic rationale may have much better results.

The basic principles of our program are:

Every patient needs a different type of enema because each one has a different type of colon (size and motility).

The only way to monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of an enema is by taking an abdominal x-ray film to determine the amount and distribution of stool in the colon before and after the enema. Every day (during 1 week), we readjust the volume, concentration, and content of the enema, according to the specific patient’s reaction and the radiologic image of his or her abdomen.

It is extremely important, as a first step, to determine the patient’s specific type of colonic motility in order to be successful. We infer this from a contrast enema.

The bowel management program at our institution was created by trial and error, out of our desperation, provoked by the follow-up of many patients who suffered from this devastating problem (fecal incontinence). During this long process (30 years), we learned many lessons, and we believe that we now have reached an important degree of expertise that allows us to have very good results, and with that, we have improved the quality of life of many children [1–3].

In dealing with anorectal malformations, clearly, a perfect initial anatomic reconstruction is only part of the job. After the operation, we are obligated to continue following our patients in order to manage the expected functional sequelae; the ultimate goal being a child with clean and dry underwear.

It is unacceptable to operate on a patient and let other professionals, not knowledgeable about our procedures, take care of the functional sequelae related to our operations.

In retrospect, from our own experience in the surgical treatment of anorectal malformations, we have learned that roughly 75 % of our patients have voluntary bowel movements [13]. This means the child is capable of verbalizing his or her desire to use the toilet voluntarily and successfully. Unfortunately, half of that 75 % group still soils the underwear occasionally. Usually those episodes of soiling are a manifestation of a degree of fecal impaction as a consequence of a mistreated problem of constipation. Once we readjust the amount of laxatives, the patient usually responds very well, and the soiling disappears. That leaves us with approximately 25 % of patients who suffer from total fecal incontinence. It is this group of patients for whom we feel morally obligated to get them clean and from whom we got the motivation to create, step by step, a series of principles and maneuvers that we now call the “bowel management program.” Soon enough, we started seeing patients not operated on by us, suffering from fecal incontinence. In fact, nowadays, most of the patients that we take care of in our bowel management clinic are patients operated on at other institutions. What we convey here is the result of an accumulated experience with the management of approximately 800 patients suffering from different types of fecal incontinence.

The bowel management program is only a medical and not a surgical treatment. Yet, most pediatricians and gastroenterologists are not familiar with this kind of management, and surgeons are usually “too busy” to perform medical treatments. As a consequence, many fecally incontinent patients remain rather abandoned, looking for centers where they can receive the benefit of a well-integrated, comprehensive, bowel management program.

We have found that bowel management programs are not popular. There are several reasons that may explain this. Hospitals like to advertise what they do, but usually they advertise “elegant” conditions and procedures. The public relations departments of hospitals like to advertise, for example, when the institution performs the first cardiac transplant, when they inaugurate a department of fetal surgery, or when they make an advance in the management of cancer. In addition, generally speaking, the media does not like to talk about fecal incontinence, stool, urine, and sexual problems. To advertise the opening of a department for bowel management is “not elegant.” In fact, we found that many doctors in the United States or in other countries perform an operation to repair an anorectal malformation, and then, when the patient goes back to their clinic suffering from fecal incontinence, the surgeons refer the patient to us, for the bowel management, and sometimes they use derogatory terms such as “go to that clinic to learn how to give enemas.” It is a very common misconception to believe that bowel management is equivalent to giving enemas. In this chapter, we try to show that the bowel management program is much more than giving an enema.

We also believe that the bowel management program is not popular because it does not pay well. Most insurance companies do not even know what a bowel management program is. As the reader will be able to learn from this chapter, it takes a significant amount of time and effort from surgeons and nurses to implement the bowel management in a single child, and insurance companies do not compensate for all this. It is rather ironic that, at the present time, a surgeon can charge about ten times more money for a 30-min operation than he can for a 1-week treatment that requires a lot of dedication and work with a child with fecal incontinence. Yet, the bowel management program allowed us to improve the quality of life, more than with any operation that we have done and in many more children.

In addition, there is certain reluctance by parents to accept the bowel management program. This is based on certain misconceptions. These include the idea that the enemas may produce malnutrition in children because some parents think that the enemas wash out nutrients from the bowel. We have to go through a long explanation, including showing diagrams, to explain that enemas only remove the waste material from the colon and not the nutrients from the small bowel. In addition, we have never seen a patient suffering from malnutrition related to the administration of enemas.

Another frequent misconception of many parents is the idea that once they start the bowel management, it is going to be for life. This concept is partly true. Many patients, of course, were born with severe anatomic defects that allow us to predict that most likely they will never have bowel control, and therefore we may reasonably believe that the bowel management will be necessary for life, unless a new scientific advance allows us to offer them something better. However, there are many other patients that have a borderline kind of bowel control, who may benefit from a temporary bowel management and who later in life develop bowel control.

Another misconception is the idea that the frequent administration of enemas will make a male patient a homosexual. There is no evidence that this could happen. Homosexuality is not more common among patients who received bowel management, and the overwhelming majority of homosexuals have never received bowel management.

Finally, many parents believe that subjecting their child to a bowel management program may interfere with the natural toilet training process. This is false. In fact, we are convinced that the bowel management may help the patient to become toilet trained. A temporary bowel management in a patient that has borderline bowel control allows the patient to gain self-confidence by feeling clean, not smelly, attend school, and play with other children without being worried about having “accidents” in the underwear. If the patient has some potential for bowel control, the bowel management is considered temporary and gives the patient the opportunity of being absolutely clean. The toilet training process can subsequently be attempted during the summer vacations, having more chance of success, particularly when the child already experienced being clean and odorless. It will be easy for a child that has been clean for several months to perceive when he is soiled with stool. A child that grows up with diapers and stool in the underwear all the time becomes accustomed to that and sometimes is more difficult to train.

Once we are successful with the bowel management regimen and keep the patients completely clean, provided the patients are old enough to understand what an operation is all about, we discuss with the parents and the patients the possibility of performing an operation that will allow the patient to receive enemas in an antegrade manner. This is through a small orifice or an artificial device, located in the abdominal wall, connected with the colon of the patient, frequently through the cecal appendix (see Chap. 21). This has been called Malone [14] or ACE procedure (antegrade continent enema). There are many techniques and different ways to do it. There is no question that these antegrade enema procedures, or techniques, are beneficial and contribute to improve the quality of life of many patients. However, we firmly believe that these procedures are only indicated when the surgeon has demonstrated that the bowel management is successful. We have seen a significant number of patients that were operated on at other institutions, undergoing different types of antegrade enema procedures; in whom the procedures were successful, but the patients were still dirty with stool in the underwear, simply because the surgeon never implemented a good bowel management program. We consider it highly inadequate to offer an antegrade enema operation to a patient in whom the surgeon never proved or demonstrated that the bowel management worked. If enemas given through the rectum fail to keep the patient clean, most likely they will be equally inefficient when given in an antegrade fashion.

20.2 Goals of the Bowel Management Program

The bowel management program was designed to take care of patients who suffer from fecal incontinence, from different origins, not only anorectal malformations. Our goal is to keep the patient artificially completely clean 24 h per day, so the patient can be socially accepted, attend school, play, and become psychologically adjusted to society.

The majority of fecally incontinent patients that we treat are patients that were born with anorectal malformations, some of them operated on by us, but the majority of them were repaired in other centers. Another group of fecally incontinent patients were born with Hirschsprung’s disease; they were operated on and subsequently suffer from fecal incontinence. This is very unfortunate because theoretically patients with Hirschsprung’s disease who are born with an intact continence mechanism, which receive a technically correct operation, should not suffer from fecal incontinence; yet, we have treated many such patients (see Chap. 24). Part of our routine evaluation of patients with Hirschsprung’s disease, who suffer from fecal incontinence, includes an examination under anesthesia to determine the integrity of the anal canal. In a technically correct operation for Hirschsprung’s, the patient’s anal canal and the dentate line should have been preserved intact. Having an intact anal canal means that the sensation (indispensable to have bowel control) most likely is preserved and also that the voluntary sphincter mechanism is most likely preserved. Unfortunately, we see many patients who had an operation that destroyed the anal canal (Fig. 20.1); the surgeon resected it during the dissection and anastomosed the normoganglionic bowel to the perianal skin, leaving no trace of anal canal, which most likely will make that patient fecally incontinent for life.

Fig. 20.1

Destroyed anal canal

Another group of patients that suffer from fecal incontinence are those who are born with myelomeningocele and spina bifida. This group represents a population of patients much larger than the population of anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung’s disease [15]. We have not been actively advertising our program in that population, because we do not have the logistic capacity to take care of so many patients, particularly with the limitations that were already mentioned, in terms of reimbursement, time, and personnel. However, we have treated a significant number of these patients who definitely benefited from our bowel management program.

Other patients were born with sacrococcygeal teratomas or other kinds of tumors in the pelvis. The tumors or the resection of those tumors damaged the structures that are important for bowel control and led the patient to suffer from fecal incontinence. Finally, patients who suffered from severe pelvic trauma that damaged the mechanism of continence may also benefit from this program. Occasionally, we take care of patients born with sacral agenesis without an anorectal malformation.

20.3 Evaluation of the Patient for Bowel Management

Characteristically, we receive letters, phone calls, or e-mails of families of patients who hear about us, from pediatricians or pediatric surgeons, or they learn about our center through the Internet. They send a letter or an e-mail asking for help. We ask them to send us copies of the operative reports of their child and request several studies that can be done at home and sent to us, or alternatively, the patient and the family may come to our center and have the studies done here. These studies include:

X-ray films of the sacrum and lumbar spine in AP and lateral positions to evaluate for scoliosis and spinal hemivertebrae and to assess the development of the sacrum from which we can partially infer the functional prognosis of the specific malformation

Kidney ultrasound and voiding cystourethrogram to evaluate for associated urologic problems

Contrast enema with water-soluble contrast material and without bowel preparation

MRI of the pelvis (Peña/Patel protocol)2 – mainly in patients born with complex malformations

MRI of the spine – to rule out the presence of tethered cord or other associated spinal and cord problems

A voiding cystourethrogram in cases with an abnormal kidney ultrasound or urinary symptoms

The purposes of performing all these studies in all patients that come to our clinic suffering from fecal incontinence include:

First, we want to find out the specific type of malformation that they were born with and their associated malformations (operative reports, x-rays of the sacrum and lumbar spine, and MRI of the spine to rule out tethered cord).

Learning about these allows us to predict whether or not the bowel management will be given on a permanent basis or temporarily (depends on the functional prognosis of the original malformation and the associated problems).

Also, this will help us to detect a very special and interesting group of patients that were born with a “good prognosis” type of defect. They underwent a technically correct operation, they never received adequate treatment for their constipation, and they suffer from overflow pseudoincontinence. They only require laxatives and no enemas!!

Second, we want to learn about the type of colonic motility that the patient has, which is the key for success. (For that we use the contrast enema.)

Third, we want to find out untreated or poorly treated associated defects (mainly urologic). This will be discussed separately due to its importance. This is the reason to request a kidney ultrasound, voiding cystourethrogram, and MRI of the spine and pelvis. We also want to know whether or not the rectum following the pull-through is located within the limits of the sphincter; the MRI done with a special technique (Peña/Patel protocol)3 is the best way to determine this.

We evaluate all those studies, elaborate a management plan, and then give the patient an appointment to come to our clinic.

A few years ago, we decided to run our bowel management program only during one specific week every month rather than daily. During that particular week, we see between 15 and 40 patients, all gathered for evaluation and management of fecal incontinence. We start the first day with a conference from one of us (surgeons) to welcome the parents and to explain generalities about the bowel management program. That is followed by a lecture by one of our nurses to talk about different types of enemas and techniques of enema administration. Then, in our clinic we see each one of the patients to discuss, on an individual basis, the kind of bowel management that we will implement, which is different in every patient, depending on the results of our evaluation.

For the following days, the patient receives the treatment (enema) we have chosen, plus the specific diet and/or medication when indicated. In addition, the parents will bring the child to the hospital every day and have an abdominal x-ray film taken. The parents then call one of our nurses daily and report to them the results of the enema. The nurse asks the parents how the patient tolerated the enema, whether or not it was uncomfortable, the reaction of the patient including vomiting and pallor (vagal reflex types of reaction), and an estimate from the parents about the amount of stool that came out with the enema. The nurses will also ask what happened in the patient’s underwear during the 24 h after the enema and how much time it took to implement the management (from the beginning of the enema application until the patient has finished evacuating his/her colon). Sometime in the afternoon, the members of our staff (surgeons and nurses) meet in a conference room, see each one of the abdominal films, and discuss the information obtained by the nurses about each one of the patients. The abdominal films show us the amount and location of the stool in the colon which reflects the efficiency of the enema. That information, plus the description of the nurse about the patient’s reaction, allows us to implement changes in the enema that may include volume, concentration, or content (ingredients) of the fluid that we use. We may also make recommendations about diet and/or medication when indicated. Our nurses then call the parents of our patients and notify them of our decision. This routine is carried out daily until we are successful. Success is defined as a completely clean and happy patient and parents. Usually, about a week after this process, 95 % of our patients are clean [1–3].

The rationales for the use of enemas, in patients suffering from fecal incontinence, are based on the idea of administering a volume of fluid in the colon to provoke a peristaltic wave, followed by a partial or total expulsion of stool (Animation 20.1). Under normal circumstances, and in the majority or our patients, the colon moves slowly; therefore, the new stool that reaches the colon will travel through it in a period of time not shorter than 24 h. During those 24 h, the patient is expected to remain clean in the underwear. It is therefore easy to understand that the success of the program depends on the efficiency of the enema to clean the colon and the motility of the colon. In other words, if the patient passes stool in the underwear, there are only two possible explanations:

A.

The enema did not clean the colon.

B.

The enema cleaned the colon, but the colon is moving too fast, and the new stool reaches the anus before 24 h (Animation 20.2).

The only way to know which one of these two circumstances is occurring is by taking an abdominal x-ray film. The presence of significant amount of stool in the colon, shortly after the administration of the enema, means that the enema is not cleaning the colon, and therefore it must be upgraded. On the other hand, a rather clean colon in a patient that is passing stool in the underwear means that the colon is moving too fast (liquid stool is not easily seen in a regular abdominal film).

20.4 Individualization of the Management

Based on the studies already mentioned, we learn several very important facts that allow us to design and individualize the management plan. It took us several years to realize that within the population of children suffering from fecal incontinence, there are two main groups of patients. The contrast enema is the most valuable study to identify these two groups:

Group A: Incontinent patients that suffer from megarectosigmoid and constipation (hypomotility of the colon) (Fig. 20.2). The majority of patients belong to this group.

Fig. 20.2

Contrast enema of a patient with megarectosigmoid and constipation (hypomotility)

Group B: Incontinent patients with a non-dilated, spastic, or short colon that suffer from a tendency to diarrhea (hypermotility of the colon). This includes patients who underwent different types of resection of the colon for a variety of reasons (Fig. 20.3). This group also includes patients who suffer from different types of enteritis or colitis (inflammatory bowel disease, food allergy, acquired phosphate enema-induced colitis, or idiopathic hypermotility).

Fig. 20.3

Contrast enema of a patient with no rectosigmoid (previously resected), hyperactive and tendency to diarrhea. (a) Diagram. (b) Contrast enema

The separation of patients into these two groups represents an essential element of our program as well as a key to success. We have not found in any of the previous publications [4–12] a description of this classification of patients. The management of patients in each group is radically different as will be described.

In Group A, patients that suffer from hypomotility (constipation) and megarectosigmoid, the management will put emphasis on trying to find the enema (large and concentrated enough) to be capable of cleaning a large floppy colon. Once we find that enema, the patient will most likely stay clean in the underwear for 24 or even sometimes 48 or 72 h due to the fact that the colon suffers from hypomotility. No special diet or medication is necessary to keep these patients clean.

Patients who belong to Group B have a hyperactive, non-dilated, spastic, or short colon (hypermotility). Such a colon is very easy to clean with a small enema. These patients need a rather small volume, not a concentrated type of enema (usually plain, normal saline solution is adequate). However, the main challenge in this group of patients is to keep the colon quiet or to reduce its peristalsis enough to avoid bowel movements in between enemas. In other words, the enema is capable of cleaning the colon very well and very easily, but because the patients have increased motility of the colon or a short colon, new stool will come out through the anus only a few hours after the administration of the enema. This can only be treated with medication to slow down the colon such as loperamide4 (Animation 20.3), pectin (a water-soluble fiber that helps bind the stool and make it bulkier), and/or a constipating diet (Fig. 20.4), depending on the severity of the hypermotility. In addition, we must try to identify and eliminate irritating factors that may be responsible for the increased colonic motility (inflammatory disease, food allergy, phosphate enemas).

Fig. 20.4

List of constipating and laxative types of food

Not recognizing these two categories of patients represents the main reason for unsuccessful attempts to keep the patients clean.

We never prescribe enemas and laxatives to the same patient, since that would make no sense. The enema is meant to clean the colon; after that, we hope to make the colon move very slowly to allow the patient to remain clean for 24 h. Giving laxatives will make the colon move fast, which will result in “accidents” (passing stool in the underwear) before the next scheduled enema.

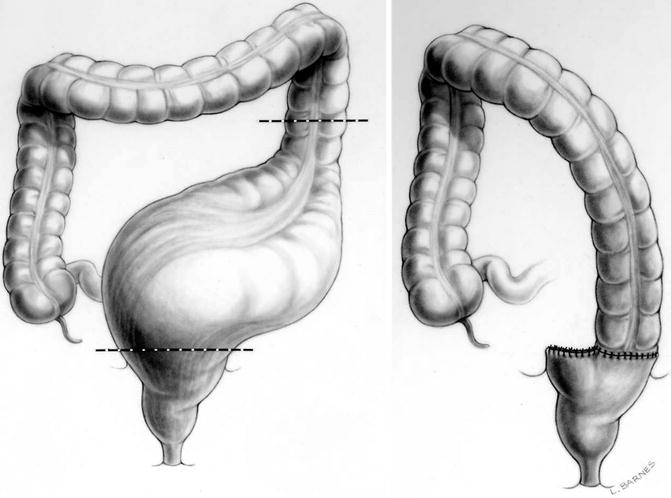

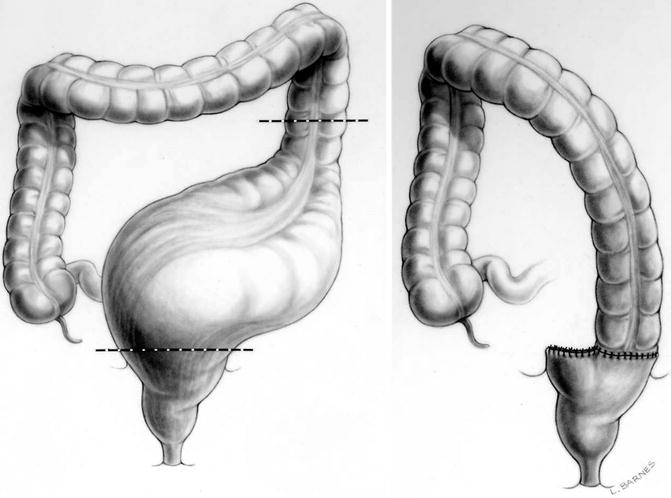

There is a small subgroup of patients that emerges from the clinical evaluation and the studies that we have already mentioned. These patients were born with what we call “benign malformations” (malformations that are associated with an excellent functional prognosis in our experience), underwent a technically correct operation, have a good sacrum, have no tethered cord, and suffer from severe constipation, and yet, they behave like fecally incontinent patients. The contrast enema shows a severe megarectosigmoid (Fig. 20.2). Interestingly, even when they were born with a “good” prognosis type of malformation and everything indicates that they should be continent, they come to our clinic complaining of “fecal incontinence.” We have learned that those patients have a great chance of suffering from what we call “overflow pseudoincontinence.” In this group, we follow a completely different strategy. The treatment consists in the administration of enemas, until the colon is completely clean, as radiologically demonstrated (disimpaction) (see Chap. 25; Animation 20.4). Once we have evidence that the colon is completely clean, we start the process of determining (by trial and error) the laxative requirements of the specific patient. We have learned that such requirements are different in each patient and much higher than what the books recommend. It is extremely important to recognize the fact that every patient will need a different amount of laxative, which is not easy to predict. The dosage of laxatives that a patient needs is defined as the amount of laxative capable of emptying the colon completely, as demonstrated radiologically (see Chap. 25). We have the patient come to the clinic every day, take an abdominal x-ray film, and increase daily the amount of laxatives, until we see a clean colon. At that point, we know the amount of laxative that the patient needs. We then ask the parents whether the bowel movements are occurring in the diaper or in the toilet. If it is in the toilet, it means that the patient is fecally continent; in fact, he/she never suffered from fecal incontinence, but actually was always “overflow pseudoincontinent.” All that he/she needed was the administration of the right amount of laxatives that had never been previously determined!! Once we determine the required amount of laxative, it is up to the parents if they are willing to give their child that amount of laxative for life in order to keep the patient clean. Alternatively, we offer them an operation designed to reduce the laxative requirement that consists in the resection of the most dilated part of the colon, preserving the rectum (Fig. 20.5), a subject that will be discussed later. This third group of pseudoincontinent patients unfortunately represents only about 5 % of our series. The diagnosis and management of this group has not been mentioned in the available literature. It is extremely rewarding to treat patients like these, because with a little effort we really dramatically change their quality of life. On occasion we see a patient with potential for bowel control and with hypermotility. In those rare patients, slowing down the colon, so the patient has one or two well-formed stools per day, allows them to perceive rectal fullness and thus succeed in having voluntary bowel movements.

Fig. 20.5

Sigmoid resection with preservation of the rectum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree