18

Benign ulceration of the stomach and duodenum and the complications of previous ulcer surgery

Management of refractory peptic ulceration

Non-HP-related refractory ulceration

Ingestion of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be re-evaluated. Surreptitious aspirin ingestion has been observed and if suspected can be established by assay of plasma salicylate levels. Any other factor that may be facilitating ulceration and impairing healing, such as intercurrent disease and smoking, should be sought and eliminated where possible. Diseases associated with peptic ulceration are chronic liver disease, hyperparathyroidism and chronic renal failure, particularly during dialysis and after successful transplantation. Smokers are more likely to fail both medical and, indeed, surgical ulcer treatment. Smoking impairs the therapeutic effects of antisecretories, may stimulate pepsin secretion and promotes reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach. Smoking increases the harmful effects of HP, and increases the production of free radicals, endothelin and platelet-activating factor. Smoking also affects the mucosal protective mechanisms by decreasing gastric mucosal blood flow and inhibiting gastric prostaglandin generation and the secretion of gastric mucous, salivary epidermal growth factor, duodenal mucosal bicarbonate and pancreatic bicarbonate.2 Stopping smoking is an important, yet often ignored, first step to allow effective ulcer treatment.

Elective surgery for peptic ulceration

Operations for refractory duodenal ulcers: There is no good evidence on which to base the decision of operation in cases of resistant ulceration in the modern era. Intuitively, one might predict a poor result with HSV alone since its success rate historically was less than that of modern medical treatment. It seems likely that resection of the antral gastrin-producing mucosa and either resection or vagal denervation of the parietal cell mass is necessary. The operations that could be considered include the following:

• Selective vagotomy and antrectomy. Selective denervation is preferred because of a lower incidence of side-effects. It is not an easy procedure; in particular, the dissection around the lower oesophagus and cardia has to be done very carefully. The vagotomy should be performed before the resection and tested intraoperatively. The reconstruction should either be a gastroduodenal (Billroth I) anastomosis or a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. The latter is associated with fewer problems with bile reflux into the gastric remnant and oesophagus, but a higher risk of stomal ulceration and so at least a two-thirds gastrectomy is advised.

• Subtotal gastrectomy. Removal of a large part of the parietal cell mass is sound in theory and indeed ulcer recurrence after this operation is unusual. However, there is an incidence of postprandial symptoms, and in particular epigastric discomfort and fullness that can limit calorie intake. Importantly, there is a high incidence of long-term nutritional and metabolic sequelae that require lifelong surveillance and can be difficult to prevent, although this is mainly in women.

• Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. This operation involves highly selective vagotomy with resection of about 50% of the parietal cell mass and the antral mucosa, but preserving the pyloric mechanism and the vagus nerves to the distal antrum and pylorus. There is some evidence that this may be a superior technique with fewer sequelae compared to the traditional approaches.3 Comparable results of the technique used in the context of treatment of early gastric cancer confirm a good long-term functional result.4

Operations for refractory gastric ulcers: There are no reliable data on which to base a recommendation for surgical treatment of refractory gastric ulcers. HSV is not recommended for pre-pyloric ulcers since they follow the same pattern as described for duodenal ulceration. The choice of operation for a more proximal ulcer, often along the lesser curve and often associated with atrophic gastritis, is between excision of the ulcer with HSV or partial gastrectomy. The recurrence rate is higher after HSV/excision, but the operative mortality is lower and side-effects fewer after this procedure.

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES)

Pathology

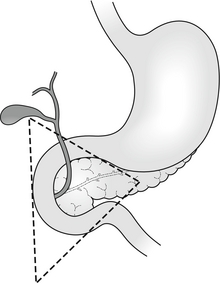

Although originally described as a pancreatic endocrine tumour, the definition has also come to include extrapancreatic gastrin-secreting tumours. The majority of tumours lie within an area defined by the junction of the cystic and common bile ducts superiorly, the junction of the second and third portions of the duodenum inferiorly, and the junction of the neck and body of the pancreas medially: the ‘gastrinoma triangle of Stabile’5 (Fig. 18.1). Where the condition is due to a pancreatic tumour, in two-thirds of cases the tumour will be multifocal within the pancreas.6 At least two-thirds will be histologically malignant. One-third will already have demonstrable metastases by the time of diagnosis.7 The most common extrapancreatic site is in the wall of the duodenum. Less frequently (6–11% of cases) ectopic gastrinoma tissue has been identified in the liver, common bile duct, jejunum, omentum, pylorus, ovary and heart.8 These extrapancreatic tumours rarely metastasise to the liver and, even though they do metastasise just as frequently to regional lymph nodes, they tend to have a better prognosis than primary pancreatic tumours.

One-quarter of patients with ZES have other endocrine tumours as part of a familial multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN-1) syndrome, particularly hyperparathyroidism.7 This group of patients has a much worse prognosis than sporadic ZES, in part due to the multifocal nature of the disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be confirmed by paradoxical fasting hypergastrinaemia associated with gastric acid hypersecretion. Hypergastrinaemia may be expected to occur in cases of achlorhydria such as ingestion of antisecretory drugs, postvagotomy, pernicious anaemia, atrophic gastritis, antral G-cell hyperplasia or gastric outlet obstruction. Hypergastrinaemia is also associated with a retained antrum after a Billroth II/Polya-type gastrectomy where a small cuff of antrum has been included in the ‘duodenal’ closure (if a retained antrum is suspected, technetium pertechnetate scan may be useful in identifying the antral mucosa). If there is diagnostic uncertainty or the basal serum gastrin level is marginal, dynamic assay of serum gastrin following secretin (or alternatively calcium or glucagon) provocation may be required. Gastrin response to a standard meal helps to differentiate hypergastrinaemia due to antral G-cell hyperplasia, which will result in an increase in serum gastrin levels, while no response would be expected in cases of gastrinoma. Serum chromogranin A, a non-specific marker for neuroendocrine tumours, should also be measured.9

Tumour localisation

Tumours may be localised initially by computed tomography (CT). This may also identify metastatic disease. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is highly accurate in the localisation of pancreatic tumours and gastrinomas in the duodenal wall as small as 4 mm. Octreotide scan and selective arterial secretagogue injection (SASI) testing are the most reliable approaches to localising gastrinomas. Liver metastases can frequently be detected by conventional imaging, but octreotide scan has proved a more sensitive investigation that may prevent unnecessary surgical exploration. SASI involves selective catheterisation of the feeding arteries of the duodenum and pancreas and the hepatic veins. Secretin is injected in turn into the splenic, gastroduodenal (GDA) and superior mesenteric (SMA) arteries. Corresponding hepatic venous gastrin levels are measured and allow identification of the main feeding vessel. More precise localisation can be achieved by more peripheral cannulation of the SMA and GDA or different points along the splenic artery. The test has greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity for preoperative tumour localisation.10

Surgery for ZES

The surgical management of ZES is characterised by controversy and little evidence. Historically, the debate centred around the radicality of surgical approaches to eliminate end organ acid production such as total gastrectomy. This is generally accepted, as unnecessary given that adequate acid suppression can usually be achieved with proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), albeit at much higher doses than those usually recommended. How aggressively surgery should be pursued for the gastrinoma itself became the next area of controversy. With adequate acid suppression, patients may be rendered asymptomatic and the natural history of the gastrinoma tended to one of only very slow progression. Nevertheless, 60–90% of gastrinomas are reported to be malignant and some do have a more aggressive course. It became more acceptable to consider resection, as 30–50% with sporadic disease may be cured or at least have a reduced rate of development of liver metastases. Whether that should be local enucleation or a wider resection remains controversial. In the past many would say that patients with MEN-1 and those with liver metastases should not be treated surgically. Nevertheless, impressive results have been reported even in the former group and there is evidence that surgical resection of metastatic liver disease does offer long-term survival, even where resection may be incomplete. One of the largest series has shown that surgical exploration and resection resulted in excellent long-term results, with a 15-year disease-related survival rate of 98% compared to 74% for non-operated cases.11

Surgical exploration when preoperative investigations have failed to precisely localise a tumour is now a less frequent problem, particularly in specialist centres with access to SASI and octreotide scan. Nevertheless, a laparotomy will detect a third more gastrinomas than even octreotide scan. If surgical exploration is performed then the pancreas must be mobilised along its entire length, inspected, palpated and if the facilities are available re-scanned intraoperatively by endoluminal or standard ultrasound. Palpation of the duodenal wall will identify 61% of duodenal gastrinomas. Duodenal transillumination by endoscopy will improve detection to 84% and duodenotomy identifies the remaining cases.12 If no gastrinoma is found in the usual locations, other ectopic sites should be examined carefully. Resection of these primary ectopic tumours can sometimes lead to durable biochemical cures. Gastrinomas may be identified in 96% of surgical explorations if these approaches are adopted.11 With the use of SASI in particular, though a tumour cannot be precisely localised, it may be sufficiently ‘narrowed down’ to allow a limited pancreatic and/or duodenal resection.10 The intraoperative secretin test in which gastrin levels in response to secretin are measured before and after resection can be useful in assessing the effectiveness of resection.

Emergency management of complicated peptic ulcer disease

Perforation

Conservative management

Study of the natural history of perforated peptic ulcers suggests that they frequently seal spontaneously by omentum or adjacent organs and that, particularly when this occurs rapidly, contamination can be minimal. Taylor showed that the mortality in his series of patients with peptic ulcer disease was half that of the contemporary (pre-1946) reported mortality for perforation treated surgically.14 Conservative treatment today consists of parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotics, intravenous acid antisecretories, intravenous fluid resuscitation and nasogastric aspiration. In addition, water-soluble meal and limited follow-through is recommended to confirm that the leak has sealed. CT is becoming increasingly used in the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain and the degree of fluid contamination may also serve as a useful guide as to whether peritoneal lavage or drainage is necessary.

Surgery

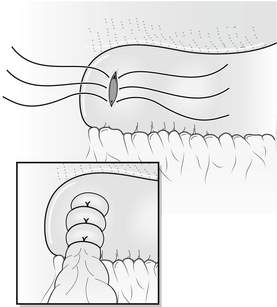

In most cases the treatment of choice for patients with perforation of the duodenum is still laparotomy, peritoneal lavage and simple closure of perforation, usually by pedicled omental patch repair (Fig. 18.2). The routine use of drains is unnecessary and may in fact increase morbidity. This simple treatment is safe and effective in the long term, when combined with pharmacological acid suppression. Ninety per cent of perforations are associated with HP infection,18 and HP eradication further significantly reduces the risk of ulcer recurrence.19

In cases of ‘giant’ perforation, where the defect measures 2.5 cm or more, partial gastrectomy with closure of the duodenal stump should be considered (see also management of bleeding from giant duodenal ulcer below). Alternatively, in situations where the clinical situation or expertise dictates more expeditious surgery, the duodenal perforation should be closed as well as possible around a large Foley or T-tube catheter to create a controlled fistula. This can be combined with venting gastrototomy and feeding jejunostomy.20 The advances in understanding of the medical treatment of peptic ulcer disease together with the decrease in experience of elective antiulcer surgery have made the argument for definitive ulcer surgery in the emergency setting almost untenable.

Although laparoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer perforation was first reported in 199021 and many excellent series have been reported since, a European population study demonstrated that the proportion of cases performed laparoscopically is as low as 6%,22 and even in centres with a specialist interest in laparoscopic surgery the proportion of cases completed laparoscopically is less than 50%.23