Fig. 1.1

Supine abdomen with osseus and nonosseus landmarks

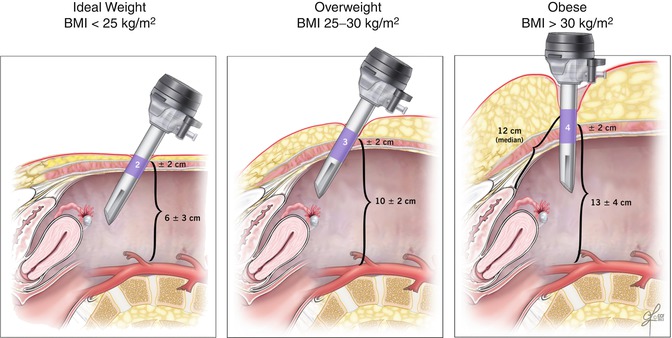

Fig. 1.2

The effect of increasing weight on anterior abdominal wall anatomy. These sagittal views illustrate that as a patient’s body mass index increases, the distance from the base of the umbilicus to the peritoneum and the distance from the base of the umbilicus to retroperitoneal structures increase. To accommodate for these increased distances, the trocar angle must move from a 45-degree angle in an ideal weight patient to almost a 90-degree angle in an obese patient in order to traverse the abdominal wall. The purple trocar area denotes the distance from the base of the umbilicus to the peritoneum at a 45-degree angle in ideal and overweight patients. In the obese patient, this distance is measured at a 90-degree angle, to mimic the recommended trocar trajectory. Furthermore, if one were to utilize a standard 45-degree trocar for insertion in the obese patient, the median distance from the base of the umbilicus to the peritoneum is 12 cm (Adapted from Hurd et al. [3])

Table 1.1

Anterior landmarks and corresponding vertebral levels

Landmark | Vertebral level |

|---|---|

Xyphoid process | T9 |

Tenth costal cartilage inferior margin | L2/L3 |

Umbilicus | Variable |

Ideal body weight | Intervertebral disc between L3/L4 |

Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) | Sacral promontory |

Inguinal ligament | |

Pubic symphysis |

1.2 Anterior Abdominal Wall

The abdominal wall from superficial to deep includes skin, subcutaneous tissue/superficial fascia, rectus sheath and muscles, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fascia, and parietal peritoneum. Several important nerves and blood vessels course through these layers.

1.2.1 Subcutaneous Tissue

Camper’s fascia is the superficial fatty layer and Scarpa’s fascia is the deeper, thin fibrous layer; collectively they represent the “superficial fascia” or subcutaneous tissue. Superficial abdominal wall vessels course through the fascia. This tissue layer tends to be deceptively prominent in obese patients.

1.2.2 Muscles and Fascia

The abdominal wall is composed of five pairs of interconnected muscles. There are two midline muscles (the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis) and three sets of lateral muscles (the external and internal obliques and the transversus abdominis). In the midline, the rectus abdominis originates from the xiphoid process and costal cartilages of the fifth to seventh ribs and extends to the pubic symphysis. This broad strap muscle is encased within the anterior and posterior rectus sheath. The aponeuroses of the rectus muscles fuse in the midline as the linea alba and fuse laterally as the linea semilunares.

The pyramidalis muscle is a small triangular muscle that lies in the rectus sheath, anterior to the inferior aspect of the rectus abdominis. Occasionally this muscle is absent on one or both sides. When it is present, it arises from the pubis and inserts into the lower linea alba.

The three lateral muscles, found bilaterally, are also referred to as flat muscles. The most superficial of these is the external oblique. It arises from the lower eighth rib, where its fibers interdigitate with the serratus anterior muscle and extend inferiorly to the linea alba and pubic tubercle, creating a broad fibrous swath known as an aponeurosis.

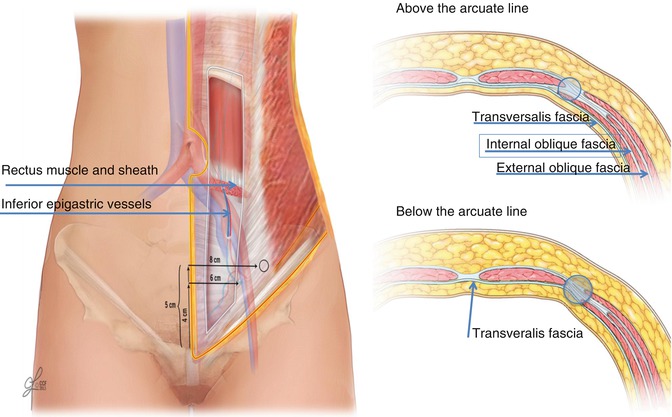

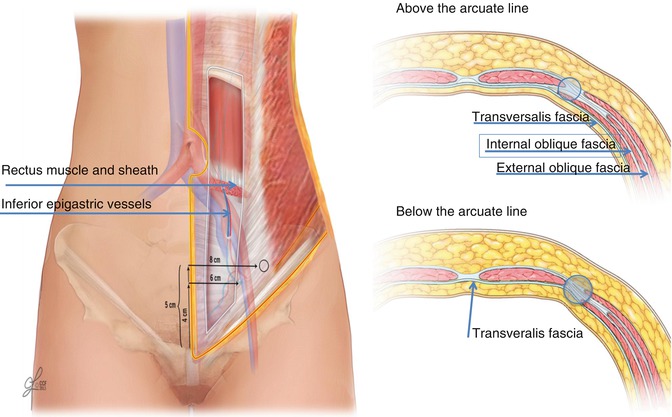

Aponeuroses are tendon-like membranes that bind muscles to each other or to bones. Posterior to the external oblique lies the internal oblique muscle, whose fibers arise from the lumbar fascia, the iliac crest, and the lateral two-thirds of the inguinal ligament. The internal oblique fibers are at right angles to the external oblique fibers. The anterior and posterior layers of the internal oblique separate into the anterior and posterior rectus sheath and are responsible for creating the arcuate line landmark. The deepest lateral muscle is the transversus abdominis. Its muscle fibers run in a transverse fashion across the abdomen. The fibers arise from the costal cartilages of the sixth to eighth ribs, interlocking with the diaphragm, the lumbodorsal fascia, the lateral third of the inguinal ligament, and from the anterior three-fourths of the iliac crest and terminate anteriorly as an aponeurosis. The transversalis fascia lies deep to the transversus abdominis and is a continuous layer that lines the abdominal and pelvic cavity (Fig. 1.3).

The arcuate line is a transverse line located midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis. Above the arcuate line, the rectus abdominis muscles possess both anterior and posterior sheaths formed by the aponeuroses of the midline and lateral muscles. Below the arcuate line, all layers of the sheaths course anterior to the rectus abdominis muscles.

The extraperitoneal fascia is the layer of connective tissue that separates the transversalis fascia from the parietal peritoneum. It contains a varying amount of adipose tissue and lines the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Viscera in the extraperitoneal fascia are referred to as retroperitoneal. Last, the parietal peritoneum lines the abdominal cavity. Remarkably, it is only one cell layer thick. Inward reflections of this peritoneum form a double cell layer known as mesentery.

The inguinal ligament is formed by the aponeuroses of the external oblique. It arises from the ASIS and inserts into the pubic tubercle. The inguinal canal runs parallel to the inguinal ligament. The inguinal canal is classically described by its four walls. Its anterior wall is formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique, the inferior wall (floor) is formed by the inguinal ligament, the superior wall (roof) is formed by arching fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, and the posterior wall is formed by the transversalis fascia.

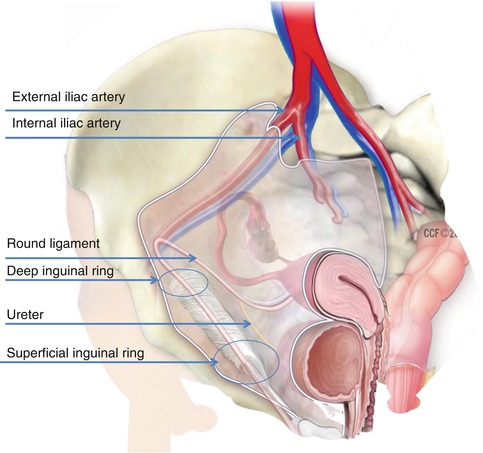

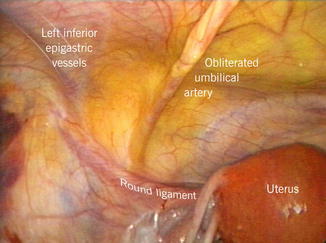

The deep internal inguinal ring is the tubular evagination of the transversalis fascia, located halfway between the ASIS and the pubic symphysis. The inferior epigastric vessels lie medial to the deep internal inguinal ring. The round ligament dives through this deep internal ring, enters the inguinal canal, exits through the superficial external inguinal ring, and terminates at the labia majora. In addition, the terminal aspect of the ilioinguinal nerve and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve exit the inguinal canal via the superficial external inguinal ring. The superficial external inguinal ring is created by the opening of the external oblique aponeurosis and is located superior and lateral to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 1.4).

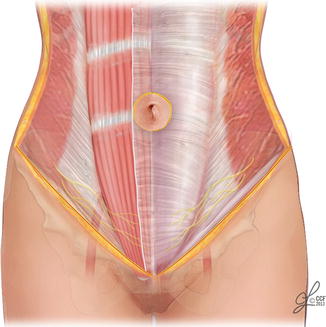

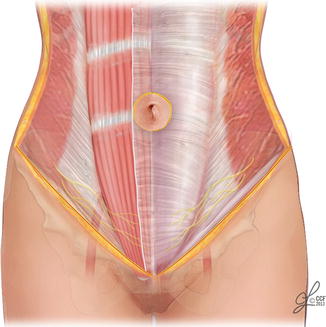

Fig. 1.3

Anterior abdominal wall muscles

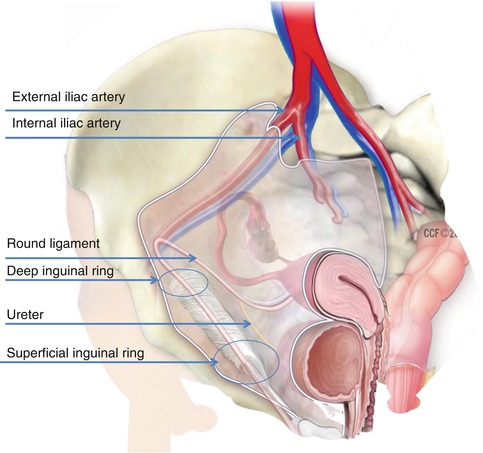

Fig. 1.4

The peritoneum drapes over the ureters, vital blood vessels, and large organs within the pelvis. The round ligament is seen entering the deep inguinal ring and exiting the superficial inguinal ring

1.2.3 Nerves

The clinically relevant upper and lower anterior abdominal wall nerves contain both motor and sensory fibers. The thoracoabdominal and subcostal nerves originate from T7 to T11 and T12, respectively. Their distributions are summarized in Table 1.2.

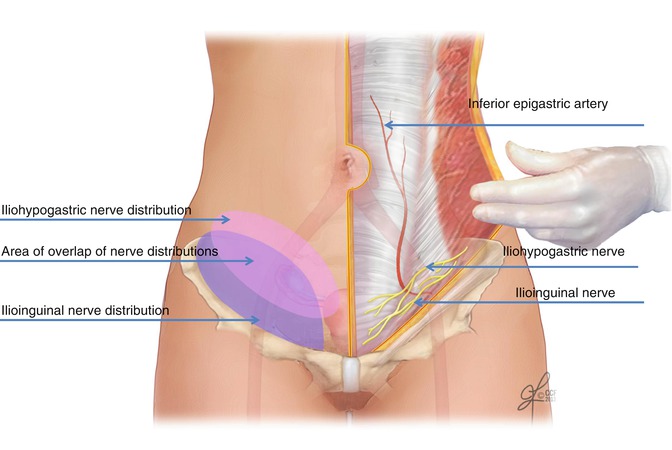

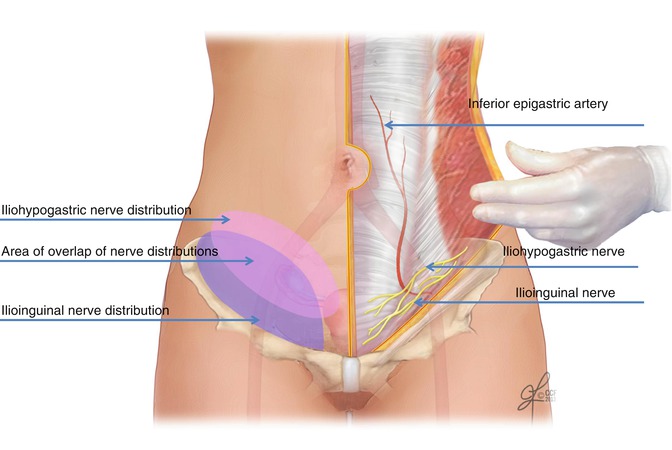

The iliohypogastric nerve and ilioinguinal nerve originate from L1 and accompany the thoracoabdominal and subcostal nerves as they course between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. At the ASIS, they traverse the internal oblique and run between the internal and external oblique muscles. The iliohypogastric nerves innervate the lateral abdominal wall, inferior to the umbilicus. The ilioinguinal nerve runs within the inguinal canal and emerges from the superficial, or external, inguinal ring to provide sensory innervation to the labia majora, inner thigh, and groin.

During laparoscopic and robotic surgery, the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves are particularly susceptible to injury because of their close proximity to traditional, lower quadrant trocar sites. Nerve damage may result from trocar placement or nerve entrapment secondary to lateral closure of transverse incisions or scar tissue (Table 1.3). The nerve injury usually results in chronic neuropathic pain (Fig. 1.5) [4].

Postoperative nerve damage should be suspected if the patient reports a burning or searing pain in the lower abdominal, pelvic, or medial thigh areas. The pain may be worsened by the Valsalva maneuver and is often relieved by hip and trunk flexion. A diagnostic and therapeutic injection of local anesthetic at the origin of the affected nerves, 3 cm medial to the ASIS, may provide relief.

Fig. 1.5

Laparoscopic port placement two fingerbreadths superior and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine usually avoids ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves and the inferior epigastric vessels

Fig. 1.6

Lower abdominal trocars should be placed lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. These vessels travel medially from their origin off the external iliac artery and course toward the umbilicus. The vessels penetrate the transversus abdominis fascia and muscle approximately 4 cm superior and 6–7 cm lateral from the pubic symphysis. They then continue to run obliquely for an additional 7 cm and enter the posterior rectus sheath. Given these landmarks, a safe area for trocar entry is 5 cm superior and 8 cm lateral to the pubic symphysis (Modified from Park and Barber [7])

Table 1.2

Anterior abdominal wall innervations

Thoracoabdominal n. |

T7–T9 superior to the umbilicus |

T10 – at level of umbilicus |

T11 – inferior to umbilicus |

Subcostal n. (anterior and lateral branches) |

T12 – inferior to the umbilicus |

Iliohypogastric n. |

L1 lateral and inferior to the umbilicus |

Ilioinguinal n. |

L1 labia majora, inner thigh, and groin |

Table 1.3

Basic principle: decrease the risk of neuropathy

Basic principle: Reduce the risk of iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerve damage by utilizing transverse skin incisions and small trocars. |

If possible, place laparoscopic trocars at or above the level of the ASIS [5]. |

If necessary, place lower abdominal trocars 2 cm medial and superior to the ASIS |

1.2.4 Blood Vessels

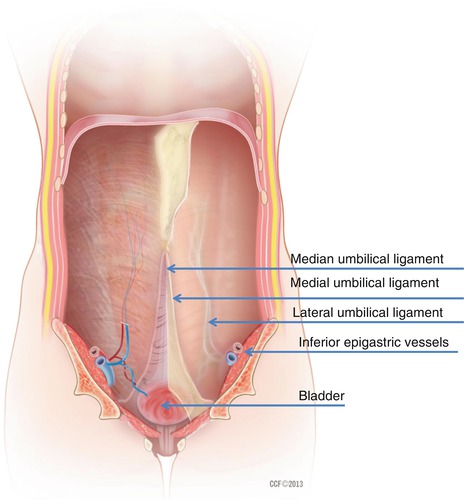

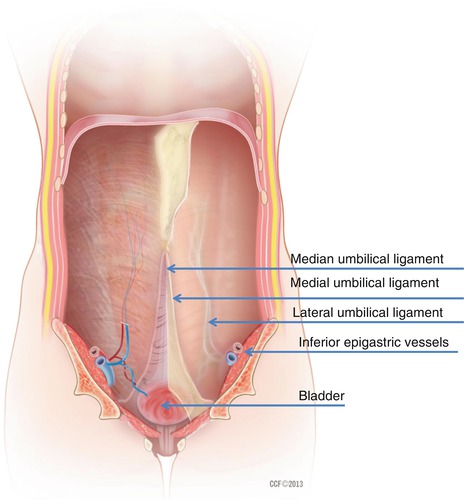

The most notable anterior abdominal wall arteries are the epigastric vessels and the circumflex iliac vessels. Both pairs of vessels can be further classified into superficial and deep vessels. The deep epigastric vessels include the superior and inferior epigastric arteries and veins. The superior epigastric artery originates from the internal mammary artery and descends through the thorax into the rectus muscle, where it anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery. The superior epigastric artery is accompanied by two superior epigastric veins. The deep inferior epigastric artery arises from the external iliac artery, just above the inguinal ligament. The inferior epigastric artery and vein travel in a medial and oblique fashion along the peritoneum to pierce the transversalis fascia and the rectus muscle. Owing to the absence of the posterior rectus sheath below the arcuate line, the inferior epigastric vessels can be seen within the lateral umbilical fold (Table 1.4) [6]. Accidental laceration of these deep vessels may result in life-threatening hemorrhage that must be swiftly occluded using electrosurgery or sutures (Fig. 1.6) [7].

In contrast, the superficial epigastric artery originates from the femoral artery and courses through the superficial fascia toward the umbilicus. Prior to placing secondary laparoscopic trocars, the superficial epigastric vessels are often identified by intra-abdominal transillumination in order to avoid vessel injuries (Table 1.5) [8].

Vascular trauma to the superficial epigastric vessels may result in a hematoma or abscess and, on rare cases, may even expand to the labia majora [9].

The circumflex iliac arteries consist of the deep and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. They arise from the femoral and external iliac arteries, respectively.

Table 1.4

Basic principle: decrease the risk of vascular injury

Always identify the deep, inferior epigastric vessels as they course along the parietal peritoneum. The deep vessels are located lateral to the medial umbilical folds but medial to the deep inguinal ring. Identify the deep inguinal ring by locating where the round ligament enters the inguinal canal and continues into the deep inguinal ring. |

If the deep epigastric vessels are obscured by excess tissue and cannot be easily identified, one of two strategies may be employed: |

1. Place the trocars approximately 8 cm lateral to the midline and 5 cm above the pubic symphysis [6]. These right and left anterior abdominal areas approximate “McBurney’s point” and “Hurd’s point,” respectively. |

Or, |

2. Place the trocar medial to the medial umbilical fold, as the inferior epigastrics are consistently lateral to these. One problem with positioning the trocar this medially, however, is poor access to the adnexa. |

Table 1.5

Basic principle: identify the vasculature

To avoid vessel injury, transilluminate the superficial epigastric and circumflex vessels, and identify their course prior to placing secondary trocars. |

1.2.5 Peritoneal Landmarks

Distorted anatomy and severe surgical scarring challenge even experienced laparoscopic surgeons. When difficult situations are encountered, it is imperative to identify key structures that will facilitate safe surgical dissection and avoid injury to retroperitoneal vessels and viscera (Table 1.6). In the midline, there are two peritoneal folds. In the upper abdomen, the falciform ligament extends from the umbilicus to the liver and includes the obliterated umbilical vein. It is a remnant of the ventral mesentery. In the pelvis, the median umbilical fold extends from the umbilicus to the apex of the bladder and encases the urachus. Occasionally, the urachus fails to close after birth and continues to communicate with the bladder. Therefore, one should avoid this fibrous fold during laparoscopic trocar placement. In addition, a pair of bilateral, medial, and lateral umbilical folds encase the obliterated umbilical arteries and inferior epigastric vessels (Figs. 1.7 and 1.8).

There are two naturally occurring peritoneal pouches within the pelvis. Located anteriorly, the vesicouterine pouch is found between the uterus and the bladder. In a pristine pelvis, the ventral aspect of the bladder may be seen behind the anterior abdominal wall peritoneum. However, after cesarean sections, myomectomies, and previous abdominal surgery this area may be scarred and the ventral bladder margin may be more cephalad than expected. Similarly, the dorsal bladder margin usually lies on the anterior surface of the uterus. It is an important landmark for avascular dissection, but after pelvic surgery it may be adherent and require meticulous dissection (Table 1.7).

Located posteriorly, the rectouterine pouch, or the pouch of Douglas, lies posterior to the vagina, cervix, uterus, and anterior to the rectum. This pocket can be completely obliterated in cases of advanced endometriosis. The scarring may extend inferiorly to the posterior wall of the vagina and the anterior wall of the rectum. This area is an extraperitoneal fascial plane known as the rectovaginal septum. On pelvic examination, endometriosis can be appreciated as palpable nodularity along this fascial plane that runs from the rectouterine pouch to the perineal body (Fig. 1.9).

Fig. 1.7

Peritoneal folds of the anterior abdominal wall. The nonmidline folds aid in identifying critical vasculature. The medial umbilical folds lie on each side of the median fold and extend from the umbilicus to the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. The medial folds contain the obliterated umbilical arteries and form the boundaries of the bladder dome. Lateral to the medial folds are the lateral umbilical folds that extend from the arcuate line to the inguinal ring. The lateral umbilical folds are vital landmarks that contain the large, inferior epigastric vessels

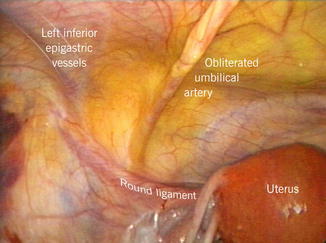

Fig. 1.8

Laparoscopic view of the left anterior abdominal and pelvic side wall. The medial umbilical fold, lateral umbilical fold, and round ligament provide peritoneal landmarks. Note that the round ligament inserts into the deep inguinal ring and is lateral to the deep inferior epigastric vessels contained within the lateral umbilical fold

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree