Serological features

Autoantibodies are an important tool for the diagnosis of AIH [12]. However, autoantibodies are not specific to AIH and their expressions can vary during the course of AIH [13]. Furthermore, a low autoantibody titer does not exclude the diagnosis of AIH and a high titer (in the absence of other supportive findings) does not establish the diagnosis. Importantly, autoantibodies do not cause the disease nor alter in titer in response to treatment (at least in adult populations); as such, they do not need to be serially monitored [12]. ANA, SMA and LKM are pivotal components for the diagnosis of AIH and should be first tested in suspicious patients [14]. ANA were the first autoantibodies to be associated with AIH and led Mackay to create the term “lupoid” hepatitis as early as 1956. ANA are the most nonspecific marker of AIH and can also be found in PBC, PSC, viral hepatitis, drug-related hepatitis, and alcoholic and non-alcoholic, fatty liver disease [15, 16]. Additionally, serum ANAs have been reported to occur in up to 15% of the general healthy populations from different countries, increasing with age. SMA are frequently found in AIH, and are directed against components of the cytoskeleton such as actin and non-actin components, including tubulin, vimentin, desmin and skeletin [15]. They frequently occur in high titers in association with ANA and are, like ANA, present in a variety of liver and non-liver diseases such as rheumatic diseases. Antibodies to LKM were first discovered in 1973 by indirect immunofluorescence and are reactive with the proximal renal tubule and hepatocellular cytoplasma [17,18]. They form a heterogeneous group and are associated with several immune mediated diseases, including AIH, drug-induced hepatitis, the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED or APS-1), and chronic hepatitis C and D infection [15]. A 50 kilo Dal ton antigen of LKM-1 was identified as the cytochrome mono-oxygenase P450 2D6 (CYP2D6). LKM-3 antibodies are directed against family 1 uridine 5’-diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A), which belong to the drug metabolizing enzymes located in the endoplasmatic reticulum.

Patients who present without these antibodies may be tested for other, characterized autoantibodies. Antibodies against LC-1, SLA/LP, pANCA and the asialoglycoprotein receptor may be helpful to extend the diagnosis of AIH in these patients. Anti-LC1 antibodies are visualized by indirect immunofluorescence. However, their characteristic staining may be masked by the more diffuse pattern of LKM-1 antibodies. Therefore, other techniques such as ouchterlony double diffusion, immunoblot and counter-immunoelectrophoresis are also used for their detection. The antigen recognized by anti-LC1 was identified as formiminotransferase cyclodeaminase (FTCD) [19]. Contrary to most other autoantibodies in AIH, anti-LC1 seems to correlate with disease activity and may be useful as a marker of residual hepatocellular inflammation in AIH [20]. Anti-SLA/LP antibodies are detectable by radioim-munoassay and enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) but cannot be detected by immunofluorescence [15]. Anti-SLA/LP antibodies are considered to be highly specific for AIH, in which they are detectable in about 10–30% of patients. In some patients, they are the only serological marker of autoimmune hepatitis. Screening of cDNA expression libraries identified a UGA tRNA suppressor as anti-SLA target autoantigen [21]. Several studies suggest that patients with anti-SLA/LP antibodies display a more severe course of the disease [22–25].

Additionally, antibodies against cardiolipin, chromatin and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been described in AIH, which, however, do not define patients with a distinctive clinical phenotype [26–28].

There have been several proposals to classify AIH according to different antibody profiles. According to this approach, AIH type I is characterized by the presence of ANA and/or anti-SMA antibodies. AIH type II is characterized by anti-LKM-1 and with lower frequency against LKM-3 antibodies. AIH type III is characterized by autoantibodies against SLA/LP. AIH-2 displays a regionally variable prevalence, with only 4% in the USA and up to 20% in western Europe [18,29]. Patients with AIH-II are younger at presentation, show a more severe course at onset and are more likely to progress to cirrhosis [30]. Both entities of AIH are characterized by a high incidence of other organ specific immune mediated diseases, for example autoimmune thyroid disease, which are not only detected in patients with AIH, but also in their first degree relatives.

Histological features

Autoimmune hepatitis cannot be diagnosed by liver histology alone, since there are no pathognomonic histological features. Histology can only support the diagnosis and is used to classify disease activity (grading) and the degree of fibrosis (staging). There is a general agreement that bridging necrosis and multilobular necrosis should be regarded as factors associated with a poor prognosis. Interface hepatitis, also known as piecemeal necrosis or periportal hepatitis, is the histological hallmark and plasma cell infiltration is typical [14, 30–32].

Up to 30% of adult patients have histological features of cirrhosis at diagnosis [5, 33]. Recent data indicate that only a small number of patients develop cirrhosis during therapy and that fibrosis scores are stable or improve in up to 75% patients [34]. However, it is important to note that the presence of cirrhosis at baseline significantly increases the risk of death or liver transplantation [5,35]. Almost half of children with AIH already have cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis [36, 37]. In elderly patients a more severe histological grade has been reported, but the frequency of cirrhosis does not seem to be different from that in younger patients [38,39].

Genetic features

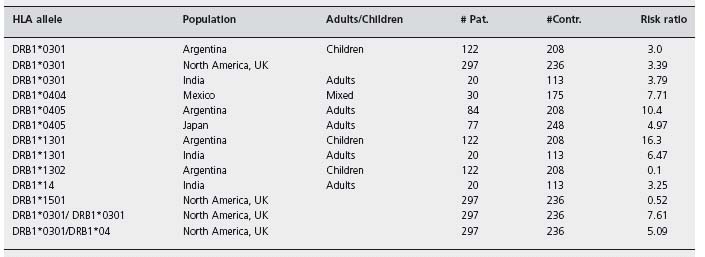

It is generally accepted that occurrence and probably the severity of autoimmune hepatitis is influenced by genetic factors. However, the heritable component of AIH is currently regarded as small. The most conclusive genetic association with autoimmune hepatitis is related to the major histocompatibility complex alleles. Among white northern European and Americans there is a well-recognized association between increased susceptibility to AIH and inheritance of HLA DR3 and HLA DR4 (later identified as DRB1*0301 and DRB1*0401 respectively) [40, 41]. HLA DR3 is the main susceptibility factor in white Caucasians, and HLA DR4 is a secondary but independent risk factor for the disease. Eighty-five percent of white patients with type I AIH from the USA and northern Europe have HLA DR3, DR4, or DR3 and DR4. Table 33.2 summarizes confirmed associations of HLA DRB1 alleles in AIH patients from different populations [42]. Based on these data, different models have been created whereby genetic susceptibility and resistance to AIH is best related to specific amino acid sequence motifs within DRB1 polypeptides. Donaldson has suggested three different models: one, for type I AIH is dependent on histidine or other basic amino acid residues at position 13 of the DRβ polypeptide; the second is based on the amino acid residue LLEQKR at positions 67–72 of the DRβ polypeptide and the third model is based on valine/glycine dimorphism at position 86 [43].

HLA alleles associated with AIH confer not only susceptibility towards AIH but also appear to influence the course of the disease. Most strikingly, patients with the DRB1*0301 were found to be younger at disease onset and have a higher frequency of treatment failure, relapse after treatment withdrawal and liver transplantation. Patients with DRB1*0401 are at greater risk to develop additional autoimmune disorders, but are thought to be associated with milder disease, seen in older patients, which is easier to treat [41,44,45].

Diagnosis

Because signs and symptoms of AIH are not specific, an international panel (the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG)) established a consensus on diagnostic criteria, and its recommendations were published in 1993 [46], and revised in 1999 [14]. These criteria include clinical, laboratory and histological findings at presentation, as well as response to corticosteroid therapy and are in most cases sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis and to distinguish it from other forms of chronic hepatitis. Response to corticosteroids may help to clarify the diagnosis even in patients who lack other typical features (see Table 33.3) [14, 30, 42, 47]. Additionally, a scoring system was established assigning points (both negative and positive) to specific findings to allow for the distinction between a definitive diagnosis and a probable diagnosis. Prior to corticosteroid treatment, a definitive diagnosis requires a score greater than 15; after treatment, a definitive diagnosis requires a score greater than 17.

The AIH scoring system was subsequently subjected to validation testing in several studies, which consistently showed that the sensitivity was very high (97–100%) but that the specificity for excluding AIH in patients with biliary disorders was markedly lower (44–65%) (see Table 33.3). The notable weakness of the original system in excluding cholestatic syndromes justified the subsequent revision to further downgrade cholestatic findings [14]. The new scoring system more precisely differentiated between biliary diseases and AIH, and application of the revised system in PBC and PSC patients revealed significantly less patients who scored for definite and probable AIH [48,49].

However, the above-described criteria were primarily introduced to allow comparison of studies from different centers. Because these criteria are complex and include a variety of parameters of questionable value, the IAIHG decided to devise a simplified scoring system for wider applicability in routine clinical practice. A limited number of routinely available measurements were therefore selected to design the score. Liver histology (demonstration of hepatitis on histology is required), autoantibody titers, gamma-globulin/IgG levels, and the absence of viral hepatitis were found to be independent predictors for the presence of AIH (see Table 33.4) [50]. The score was found to have good sensitivity and specificity in a second validation set. Therefore a simple score based on four measurements may be sufficient to differentiate between patients with or without AIH, with a high degree of accuracy. However, additional studies are required to validate this score in patients with different chronic liver diseases.

Treatment

The indication for treatment of AIH is based on inflammatory activity and not so much on the presence of cirrhosis. In the absence of inflammatory activity immunosuppres-sive treatment has only limited effects. An indication for treatment is present when aminotransferases are elevated two-fold, gamma globulin levels are elevated two-fold and histology shows moderate to severe periportal hepatitis. Symptoms of severe fatigue are also an indication for treatment. An absolute indication exists in cases with a ten-fold or higher elevation of aminotransferase levels, histological signs of severe inflammation and necrosis, and upon disease progression.

Table 33.3 Scoring system for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

| Parameter | Score |

| Gender | |

| Female | +2 |

| Male | 0 |

| Serum biochemistry | |

| Ratio of elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase vs aminotransferase | |

| >3.0 | −2 |

| <3.0 | +2 |

| Total serum globulin, γ – globulin or IgG | |

| Times upper normal limit | |

| >2.0 | +3 |

| 1.5 – 2.0 | +2 |

| 1.0 – 1.5 | 2.0 +1 |

| <1.0 | 0 |

| Autoantibodies (titers by immunfl uorescence on rodent tissues) | |

| Adults | |

| ANA, SMA or LKM – 1 | >1 : 80 |

| +3 | 1 : 80 |

| +2 | 1 : 40 |

| +1 | <1 : 40 |

| 0 | Children |

| ANA or LKM – 1 | |

| >1 : 20 | +3 |

| 1 : 10 or 1 : 20 | +2 |

| <1 : 20 or SMA | 0 |

| >1 : 20 | +3 |

| 1 : 20 | +2 |

| <1 : 20 | 0 |

| Antimitochondrial antibody | |

| Positive | −2 |

| Negative | 0 |

| Viral markers | |

| IgM anti – HAV, HBsAg orIgM anti – HBc positive | −3 |

| Anti – HCV positive by ELISA and/or RIBA | −2 |

| HCV positive by PCR for HCV RNA | −3 |

| Positive test indicating active infection with any other virus | |