Chapter 3 Assessment of Quality of Life (QoL) (A) Global Generic QoL Assessments (B) Disease-Specific QoL Instrument Increasingly, authorities and the medical community request that quality of life assessments are conducted as one of the primary or secondary aims of a medical pharmaceutical or technological trial. It is not the purpose of this book to give an elaborate account of the many QoL engines available. It would in fact be impossible because questionnaires need to be applied in a validated language that obviously differs geographically. Rather a summary of the most essential features of many currently available QoL assessments is given. The interested reader is referred via the most appropriate references to the actual methodology used in those measurements. Two major types of health-related QoL (HRQoL) measurements are available: (a) global assessment, with generic or general instruments, and (b) disease-specific instruments. Generic instruments use generalized questions that are not specific to any particular disease. Generic HRQoL, which allow comparison across a broad spectrum of diseases, may not be responsive to a clinically important change for a particular disease. Global assessments in the form of a graded summary (good, fair, poor) or using a visual analogue scale are often inadequate for complex hypothesis testing. Disease-specific questionnaires are designed to detect HRQoL that may not be targeted in generic instruments. In assessing symptoms, quality of life, and patient satisfaction, the focus is on “measurement” and “quantification.” Regardless of whether a diary or questionnaire is the chosen method of data collection, the objective is to collect information (generally from the patients themselves) on personal circumstances, perceptions, behavior, attitudes, expectations etc. Validity refers to whether the question is adequately measuring the construct or concept of interest. A number of different aspects of validity need to be taken into account: • Face validity: whether “on the face of it” the question(s) are measuring what they are supposed to measure. • Content validity: whether the choice of items and the relative importance given to each is appropriate in the eyes of those who have some knowledge of the topic area. • Construct validity: whether the results obtained using the questionnaire confirm expected statistical relationships, the expectations being derived from underlying theory. A way of establishing construct validity is through multi-trait multi-method analysis. It involves administering more than one instrument that purport to measure similar domains of health and examining the correlation between scores on the various instruments. • Criterion validity: whether the question/questionnaire yields results which correspond with those obtained by another “gold-standard” method, applied simultaneously (concurrent validity) or which forecast a criterion value (predictive validity). • Freedom from absolute or relative bias: whether the question/questionnaire yields results which fairly reflect the distribution of some target variable in the population and in subpopulations. Reliability refers to whether the question or questionnaire is measuring things in a consistent or reproducible way. • Test–retest reliability: this is the most logically straightforward measure of reliability. It involves checking whether the same answer is obtained if the question is asked of the same individual at two points in time, during which period no real change has occurred in that individual in relevant respects. • Internal consistency: whether responses to questions measuring the same or a related concept are consistent with each other. The degree of logical and conceptual consistency found between responses to questions designed to capture the same property of a subject provides an indication of the reliability of those responses. • Within-rater (within-observer, within-interviewer) reliability and between-rater (between-observer, between-interviewer) reliability are special cases of test-retest reliability. The first refers to whether the same data collector or assessor (usually an interviewer in the context of questionnaire methods, but in other contexts it could be a diagnostician or observer) obtains the same responses from a given individual on two occasions, given that no real change has occurred in the meantime. The second refers to whether or not two (or more) different interviewers obtain the same responses from a given individual, given no real change. Bias can be defined as “any process at any stage of inference, which tends to produce results or conclusions that differ systematically from the truth.” Throughout the data collection process, there is the potential for bias to be introduced. It is possible for a measure to be reasonably valid (measuring the right thing) and reasonably reliable (free of random error), but still subject to serious bias (producing “readings” that are systematically too high or too low). The various instruments summarized in this chapter have been extracted from the recent gastrointestinal literature as indicative of their current use in gastrointestinal–hepatologic clinical studies and drug evaluations. As already indicated, it is impossible to discuss in detail all possible quality of life (QoL) assessments commonly used in gastroenterology. Only an overview and the essence of the various QoL assessments will be given with a few more extensive examples of questionnaires used in practice. The reader is referred to the original publication for more detailed information regarding other questionnaires and the methodology used to calculate the various scores. For a critical analysis of generic or disease-specific instruments in general the reader is referred to following literature surveys: Borgaonkar MR, Irvine EJ. Quality of life measurement in gastrointestinal and liver disorders. Gut. 2000;47:444–454. Eisen GM, Locke GR 3rd, Provenzale D. Health-related quality of life: a primer for gastroenterologists. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8): 2017–21. Yacavone RF, Locke GR 3rd, Provenzale D, Eisen GM. Quality of life measurement in gastroenterology: What is available? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(2):285–97. The following QoL assessments will be discussed: • SF-36; SF-24; SF-12; • PGWBI (psychologic general well-being index); • SIP (sickness impact profile); • WHOQOL—WHOQOL-BREF; • EuroQol (EQ-5D); • EORTC-QLQ-C30, QLQ-PAN 26; • General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28); • Impact on Daily Activity Scale (IDAS); • Clinical Global Impression (CGI); • Quality of Well-being Scale (QWB); • Illness Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ); • McGill Pain Questionnaire; • Sheehan’s Disability Scale (DISS); • Symptom Check List 90 (SCL-90); • Global Severity Index (GSI); • Complaint Score Questionnaire (CSQ); • Göteborg Quality of Life Instrument; • Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD); • Anxiety and Depression Scaling according to Goldberg; • Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); • Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Score; • Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); • Hamilton Psychiatric Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (HAMD); • Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; • Center of Epidemiological Studies/Depression Scale (CES-D); • Psychosomatic Symptom Checklist (PSC); • CPRS, CPRS-S-A; • Karolinska Scales of Personality (KSP); • EPQ, DSSI, SPHERE, HUI; • Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI) Life Events Scale; • The Holmes and Rahe Schedule of Recent Experience (SRE); • Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ); • Locus of Control Behavior (LCB); • SCID; • Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS); • Social Support Questionnaire-6 (SSQ); • Grogono and Woodgate Index; • Rand QOL; • Nottingham Health Profile (NHP); • Cleveland Global Quality of Life Scale (CGQL); • McMaster Health Index Questionnaire; • The Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSC); • Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); • Jalowiec Coping Scale (JCS-40); • Freiburg Questionnaire of Coping with Illness (FQCI); • Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS); • Fatigue Score according to Wessely; • Fatigue Severity Scale according to Krupp; • Sleep Scale according to Yacavone; • Sleep Habit Questionnaire; • Geriatric Assessment Scales; • The Abuse Severity Index according to Leserman; • Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLP) Questionnaire; • Overall Treatment Effect Scale (OTE); • QHES; • QOL5. The 36-item short form (SF-36) was designed by the medical outcomes trust to survey health status in medical outcomes studies, and is called the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 Questions SF-36 Response choices In general, would you say health is: Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor Compared to one year ago, how would you rate your health in general now? Much better now than one year ago, Somewhat better now than one year ago, About the same as one year ago, Somewhat worse now than one year ago, Much worse than one year ago The following items are about activities you might do during a typical day. Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so, how much? a. Vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports; b. Moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf; c. Lifting or carrying groceries; d. Climbing several flights of stairs; e. Climbing one flight of stairs; f. Bending, kneeling, or stooping; g. Walking more than a mile; h. Walking several blocks; i. Walking one block; j. Bathing or dressing yourself. Yes, Limited a lot; Yes, Limited a little; No, Not limited at all During the past 4 weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of your physical health? a. Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities; b. Accomplished less than you would like; c. Were limited in the kind of work or other activities; d. Had difficulty performing the work or other activities (for example, it took extra effort). a–d Yes, No During the past 4 weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of an emotional problem (such as feeling depressed or anxious)? a. Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities; b. Accomplished less than you would like; c. Didn’t do work or other activities as carefully as usual. a–c Yes, No During the past 4 weeks, to what extent has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your normal social activities with family, friends, neighbors, or groups? Not at all, Slightly, Moderately, Quite a bit, Extremely How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks? None, Very mild, Mild, Moderate, Severe, Very severe During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work (including both work outside the home and housework)? Not at all, A little bit, Moderately, Quite a bit, Extremely These questions are about how you feel and how things have been with you during the past 4 weeks. For each question, please give the one answer that comes closest to the way you have been feeling. How much of the time during the past 4 weeks: a. Did you feel full of pep? b. Have you been a very nervous person? c. Have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? d. Have you felt calm and peaceful? e. Did you have a lot of energy? f. Have you felt down-hearted and blue? g. Did you feel worn out? h. Have you been a happy person? i. Did you feel tired? All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, A little of the time, None of the time During the past 4 weeks, how much time has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting with friends, relatives, etc.)? All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, A little of the time, None of the time How TRUE or FALSE is each of the following statements for you? a. I seem to get sick a little easier than other people; b. I am as healthy as anybody I know; c. I expect my health to get worse; d. My health is excellent. Definitely true, Mostly true, Don’t know, Mostly false, Definitely false From Ware JE, Sherbourne CE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptional frame work and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). Eight health concepts are measured: (1) physical functioning; (2) role limitations because of physical health problems; (3) bodily pain; (4) social functioning; (5) general mental health (psychological distress and psychological well-being); (6) role limitations because of emotional problems; (7) vitality (energy/fatigue); and (8) general health perceptions. For each question, raw scores are coded, summed, and transformed into a scale from 0 (worst possible health state measured) to 100 (best possible health state) following the standard SF-36 scoring algorithms. The test can be self-administered for patients 14 years of age and older and by trained persons by telephone. The SF-36 is the most widely accepted measure of quality of life. However, it is cumbersome to use and requires complicated analysis. McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. Ware JE, Sherbourne CE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptional frame work and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. Ware JR, Snow KK, Kosinsky M, Gandeck B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. Ware JE Jr. The SR-36 Health Surrey. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:117–31. The MOS (medical outcomes study 24 questionnaire; MOS-24) is an abridged version of the medical outcomes study Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire. The MOS-24 comprises 24 questions that are summarized in 7 subscales, each ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better health. Subscales address the following items: physical functioning, role functioning, mental health, social functioning, general health, vitality or energy, and pain. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724–735. SF-12 is a 12-item generic quality of life measure that assesses mental and physical functioning. Examples of questions assessing mental functioning include “Have you felt calm and peaceful?” and “Have you felt downhearted and blue?”. Physical functioning is addressed with questions such as “During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work?” Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and health summary scales. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. The PGWB was designed to measure subjective well-being or distress. The PGWB index is a self-administered health-related quality of life questionnaire, which has been extensively documented with regard to reliability and validity. The PGWB index includes 22 items, divided into six dimensions, each of which is divided into 3–5 items: • Anxiety (degree of nervousness, degree of tension, anxiety, state of relaxation, stress) • Depressed mood (depressed, down-hearted, sad) • Positive well-being (generally in high spirits, happy, interested in daily life, cheerful) • Self-control (firm control, afraid of losing control) • General health (bothered by illness, healthy enough to do things, concerned about health) • Vitality (has energy, awakens feeling rested, has vigor, degree of tiredness) A six-point Likert scale is used as the response format, with the higher the value, the better the well-being. From the answers to the items, one overall PGWB index score and six-dimensional scores without overlapping items can be derived. The 22 items cover the six dimensions. The total score gives a value that ranges from a maximum of 132 to a minimum of 22. The dimensional scores are calculated in a similar way, the score ranges being 3–18, 1–24 or 5–30 depending on the number or items that are included in each dimension. This index has been applied in studies of dyspepsia and reflux disease and there are extensive normative data available. Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B, Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. An improved evaluation of treatment regimens. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:681–687. Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B, Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. Well-being and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients referred to endoscopy owing to suspected duodenal ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1046–1052. Dupuy HJ. The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) Index. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CF, Elinson J, eds. Assessment of Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of CardioVascular Therapies. Darien, Connecticut: Le Jacq Publishing Inc.; 1984:170–183. Naughton MJ, Shumaker SA, Anderson RT et al. Psychological aspects of health related quality of life measurement. Tests and Scales. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmaco-economics in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:117–131. Wiklund I, Karlberg J. Evaluation of quality of life in clinical trials. Selecting quality-of-life measures. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12(4):204–216. The SIP is a reliable and valid self-report measure of health-related dysfunction that contains 136 statements related to 12 categories of activity (Ambulation, Body Care and Movement, Mobility, Emotional Behavior, Social Interaction, Recreation and Pastimes, Home Management, Eating, Sleep and Rest, Communication, Work, and Alertness Behavior). Patients endorse only those items that describe their current health status with higher scores indicating greater levels of dysfunction in each category of activity. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805. The extensive work by the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) investigators demonstrates that although different cultures may use the same primary language, differences in the meaning and the ranking of word descriptors may produce psychometrically noncomparable results if this important qualitative phase is ignored. WHOQOL is a reasonably well-validated but rather lengthy instrument. The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–85. WHOQOL-BREF is a shorter version of the rather lengthy WHOQOL. The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8. The EuroQol EQ-5D questionnaire is a simple, generic instrument for describing and valuing HRQOL. It has been developed by an international and interdisciplinary group of researchers to generate an index value for HRQOL. Index values obtained from the EQ-5D reflect the subjective valuation of health states based on the respondents’ references. For various countries, there exist index values for health states described by the EQ-5D that were generated from surveys of the general public. Both forms of index values may be used in evaluating changes in health status, with one reflecting the values of beneficiaries of care and the second reflecting community references. The validity and reliability of the EQ-5D have been shown for various diseases as well as for the general population. Validated translations are available for 20 languages. The EQ-5D questionnaire comprises five questions (items) relating to problems in the dimensions “mobility,” “self-care,” “usual activities,” “pain/discomfort,” and “anxiety/depression.” Responses in each dimension are divided into three ordinal levels: coded (1) no problems; (2) moderate problems; and (3) extreme problems. This part, called the EQ-5D self-classifier, provides a five-dimensional description of health status, which can be defined by a five-digit number. Theoretically, 243 different health states can be defined, The EQ visual analogue scale (EQ VAS score) is a 20 cm, vertical, hash-marked scale on which respondents are asked to rate their overall health between 0 (worst imaginable health state) and 100 (best imaginable health state). The EQ Index consists of a general population reference value for each of the 243 health scales generated by the descriptive system. Fig. 3.1 EQ VAS score. From The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. With permission of Elsevier. Fig. 3.2a, b EQ index. Brooks R, with the EuroQol Group. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. Kind P. The EuroQol instrument. An index of health related quality of life. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmaco-economics in Clinical Trials. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996:191–201. The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16: 199–208. For a complete listing of References see www.euroqol.org. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a valid and reliable measure of QL that has been tested in patients with cancer of the esophagus. It includes five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and emesis), and one global health scale. Single items are designed to assess additional symptoms (dyspnoea, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, constipation, and diarrhea). The last item is related to the perceived financial impact of the disease and its treatment. QL scores were calculated according to standard guidelines, yielding a range of 0–100. Scoring algorithms have been produced by the EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. All scale and item scores range from 1 to 100. In the functional scales a high score is equivalent to better function, whereas in the symptom scales and single items a high score means more severe symptoms. Although this instrument is specific for oncology patients, it is not specific for gastrointestinal malignancy. The current version 3.0 differs in three respects from the first version: the role functioning and overall quality of life scales have been changed, and the dichotomous response format of the items of the physical functioning scale has been replaced by four-point Likert-type response categories. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. Blazeby JM, Alderson D, Winstone K et al. Development of an EORTC questionnaire module to be used in quality of life assessment for patients with oesophageal cancer. The EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1912–1917. Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. Brussels: Quality of Life Unit, EORTC Data Centre; 1995. Fayers P, Bottomley A, EORTC Quality of Life Group, Quality of Life Unit. Quality of life research within the EORTC—the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(4):125–133. Sprangers MA, Cull A, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Aaronson NK. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Approach to quality of life assessment: guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:287–295. www.eortc.be. The GHQ-28 is used to assess the subject’s psychosocial functioning. It comprises four subscales measuring anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms, and social dysfunction. There are seven items in each subscale, each item scored on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (best score) to 3 (worst score). Scores for each subscale and a total score can be derived. The total score ranges between 0 points (“maximum well-being”) and 84 points (“severe discomfort“). The GHQ was designed to identify short-term changes in mental health. The questionnaire was originally constructed to defect minor psychiatric illness in primary care or outpatients. The index focuses on the ability of the patient to carry out normal functions and the appearance of any new disturbing phenomena. Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9:139–145. Goldberg D, Williams P. A User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988. IDAS consists of six questions measuring one’s ability to execute daily life activities. The measured activities include housework, sport or leisure activities, sleep, daily life, and employment. Each answer is scored on a 7-point scale, with a higher total score indicating better well-being. Wiklund I, Glise H, Jerndal P, Carlsson J, Talley NJ. Does endoscopy have a positive impact on quality of life in dyspepsia? Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:449–454. The CGI consists of three global scales (items) that have been designed to measure the severity, global improvement, and efficacy of treatment of patients diagnosed with depression. Global Improvement is the 2nd scale in the CGI. Total overall improvement is judged by whether or not, the improvement is entirely due to the drug treatment. It is a 0–7 point weighted scale, going from not assessed (0) to very much worse (7), respectively. Guy W. Clinical Global Impressions. New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (ECDEU) Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Department of Health; 1976:218–222. The Quality of Well-Being Scale is the first published generic health-related quality of life measure. It rates current health status and weights that health state by its desirability. The QWB calculates the patients’ point-in-time well-being scores, ranging from 0 (death) to 1.0 (asymptomatic optimum functioning), by incorporating their function levels (on the mobility, physical activity, and social activity scales), adjusted for problems or symptoms. By multiplying the QWB scores by expectant length of time spent at each functional level and by summing, a symptom-standardized life expectancy in well-year equivalents is yielded. Kaplan RM, Anderson JP. The general health policy model: An integrated approach. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmaeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996;309–322. The IBQ is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 62 items which evaluate a patient’s own feelings and ideas about illness. The seven scales are: general hypochondria (GH), disease conviction (DC), psychologic versus somatic perception of illness (PS), affective inhibition (AI), affective disturbance (AD), denial of emotional problems (D), and irritability (I). There are also two second-order factors: the illness state, based on DC and PS scales; and the affective state, derived from GH, AD, and I scales. Pilowsky I, Spence N, Cobb J, Katsikitis M. The Illness Behavior Questionnaire as an aid to clinical assessment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1984;6:123–130. The McGill Pain Questionnaire consists primarily of three major classes of word descriptors—sensory, affective, and evaluative—that are used by patients to specify subjective pain experience. It also contains an intensity scale and other items to determine the properties of pain experience. The questionnaire was designed to provide quantitative measures of clinical pain that can be treated statistically. The three major measures are: (1) the pain rating index, based on two types of numerical values that can be assigned to each word descriptor; (2) the number of words chosen; and (3) the present pain intensity based on a 1–5 intensity scale. Examples of the questionnaire are shown in the figures and scales. The data, taken together, indicates that the McGill Pain Questionnaire provides quantitative information that can be treated statistically, and is sufficiently sensitive to detect differences among different methods to relieve pain. Fig. 3.3 McGill pain questionnaire. From Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. With permission for the International Association for the Study of Pain. Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. The discretized analogue disability scale (DISS) is designed as a short, simple, cost-effective, sensitive measure of disability and functional impairment in psychiatric disorders. It uses visual– spatial, numeric, and verbal descriptive anchors to assess disability across three domains: work, social life, and family life. Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(3):89–95. The Hopkins SCL-90 is a validated self-rated questionnaire, consisting of 90 items, scored on a five-point Likert scale, designed to assess various dimensions of psychopathology. It consists of nine clinical scales for somatization (SOM), obsessive-compulsion (OC), interpersonal sensitivity (INT), depression (DEP), anxiety (ANX), hostility (HOS), phobic anxiety (PHOB), paranoid ideation (PAR), and psychoticism (PSY). The respondent is asked to consider how distressed or bothered he felt by the items during the past 7 days and rate them as 0: not at all; 1, a little bit; 2, moderately; 3, quit a bit; 4, extremely. Furthermore, a global severity index (GSI) was obtained by dividing the total score by the number of items. Clinically important distress corresponds to T-scores of ≥ 63. This scale does not yield psychiatric diagnoses. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale-preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:280–289. Derogatis LR. SCL-90R. Symptom Checklist-90-R. Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. 3rd ed. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1994. The GSI measures psychologic distress. The GSI provides a summary score that combines the number and intensity of symptoms. Descriptive results are reported as T-scores (normative mean score = 50, SD = 10) and clinically important distress corresponds to T-scores of 63 and greater. Turnbull GK, Vallis TM. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: the interaction of disease activity with psychosocial function. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1450–1454. The CSQ consists of 30 questions (yes/no) about the occurrence of different physical and mental symptoms during the past three months. The symptoms may be divided into seven clusters depicting: depression (5 symptoms), tension (4 symptoms), gastrointestinal/urinary tract (6 symptoms), musculoskeletal (3 symptoms), metabolism (4 symptoms), heart/lung (3 symptoms), head (4 symptoms). The Göteborg Quality of Life instrument assesses levels of general health and their effect on well-being. The reliability and validity has been shown in community-based studies in Sweden. Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Bengtsson C, Furunes B, Lapidus L, Lissner L. “The Göteborg Quality of Life Instrument”—a psychometric evaluation of assessments of symptoms and well-being among women in a general population. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1993;11:267–275. Tibblin G, Tibblin B, Peciva S, Kullman S, Svardsudd K. “The Göteborg quality of life instrument”—an assessment of well-being and symptoms among men born 1913 and 1923. Methods and validity. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl. 1990;1:33–38. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale was developed for use in medical outpatients. In the construction of this scale symptoms that might arise equally from somatic and mental disorders were excluded, which means that the scale scores are not affected by bodily illness. The HAD scale is a reliable instrument, with “cut-off” scores, for screening for clinically significant anxiety and depression in patients attending a general medical clinic and has also been shown to be a valid measure of the severity of these disorders of mood. This validated self-assessment mood scale consists of 14 items, each using a four-grade Likert scale (0–3) (0 = indicating no distress; 3 = indicating maximum distress), with subscales for anxiety (seven items) and depression (seven items) graded for severity. The items are summed and categorized into two dimensions (anxiety and depression), with a sum score ranging from 0 to 21. A score of [L50872] 7 on either dimension is suggested to indicate a “non-case”, 8–10 as a “possible case” and ≥ 11 as a “case” of anxiety or depression. The higher the score, the higher the level of depression and anxiety, respectively. An advantage of this measure is that it avoids counting somatic symptoms such as fatigue and palpitations. Patients are asked to choose one response from the four given for each question. They should give an immediate response and be dissuaded from thinking too long about their answers. The questions relating to anxiety are marked “A” and to depression “D.” The score for each answer is given in brackets before the answer. A I feel tense or “wound up”: (3) Most of the time (2) A lot of the time (1) From time to time, occasionally (0) Not at all D I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy: (0) Definitely as much (1) Not quite so much (2) Only a little (1) Hardly at all A I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen: (3) Very definitely and quite badly (2) Yes, but not too badly (1) A little, but it doesn’t worry me (0) Not at all D I can laugh and see the funny side of things: (0) As much as I always could (1) Not quite so much now (2) Definitely not so much now (3) Not at all A Worrying thoughts go through my mind: (3) A great deal of the time (2) A lot of the time (1) From time to time, but not too often (0) Only occasionally D I feel cheerful: (3) Not at all (2) Not often (1) Sometimes (0) Most of the time A I can sit at ease and feel relaxed: (0) Definitely (1) Usually (2) Not often (3) Not at all D I feel as if I am slowing down: (3) Nearly all the time (2) Very often (1) Sometimes (0) Not at all A I get a sort of frightened feeling like “butterflies” in the stomach: (0) Not at all (1) Occasionally (2) Quite often (3) Very often D I have lost interest in my appearance: (3) Definitely (2) I don’t take as much care as I should (1) I may not take quite as much care (0) I take just as much care as ever A I feel restless as if I have to be on the move: (3) Very much indeed (2) Quite a lot (1) Not very much (0) Not at all D I look forward with enjoyment to things: (0) As much as I ever did (1) Rather less than I used to (2) Definitely less than I used to (3) Hardly at all A I get sudden feelings of panic: (2) Quite often (1) Not very often (0) Not at all D I can enjoy a good book or radio or TV program: (0) Often (1) Sometimes (2) Not often (3) Very seldom From Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:17–41. The short scales measuring anxiety and depression are designed to be used by nonpsychiatrists; they provide dimensional measures of the severity of each disorder. The full set of nine questions needs to be administered only if there are positive answers to the first four. Patients with anxiety scores of five or depression scores of two have a 50 % chance of having a clinically important disturbance; above these scores the probability rises sharply. Anxiety scale (score one point for each ‘Yes’) 1. Have you felt keyed up, on edge? 2. Have you been worrying a lot? 3. Have you been irritable? 4. Have you had difficulty relaxing? If ‘Yes’ to two of the above, go on to ask: 5. Have you been sleeping poorly? 6. Have you had headaches or neck aches? 7. Have you had any of the following: trembling, tingling, dizzy spells, sweating, frequency, diarrhoea? 8. Have you been worried about your health? 9. Have you had difficulty falling asleep? Depression scale (score one point for each ‘Yes’) 1. Have you had low energy? 2. Have you had loss of interests? 3. Have you lost confidence in yourself? 4. Have you felt hopeless? If ‘Yes’ to ANY question, go on to ask: 5. Have you had difficulty concentrating? 6. Have you lost weight (due to poor appetite)? 7. Have you been waking early? 8. Have you felt slowed up? 9. Have you tended to feel worse in the mornings? From Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ. 1988;297: 897–899. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ. 1988;297:897–899. The STAI is a self-reporting instrument used to measure both anxiety resulting from acute stressors (state anxiety) (STAI-S) and the patient’s intrinsic level of anxiety irrespective of any particular acute stressor (trait anxiety) (STAI-T). It is the most widely used state and trait anxiety scale. Adequate reliability and validity estimates have been established in several studies. The STAI-S consists of 20 items that ask respondents to report what they feel at a particular moment in time, and the STAI-T consists of 20 statements that ask respondents to report what they generally feel. The STAI-S is usually administered along with the STAI-T in the same scaling format and uses the same four-point Likert scale (1–4) ranging from almost never to almost always, which means that the higher the score, the higher the level of anxiety. A value of 45 indicates existing anxiety in both “state” and “trait” scales. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State—Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1983. The Zung self-rating anxiety scale is a widely used 20-item inventory of symptoms related to anxiety. Scores greater than 0.625 indicate anxiety. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–379. The Beck Depression Inventory is a widely used 21-item self-report inventory of depressive symptoms. Scores greater than 15 indicate depression. 1 0 I do not feel sad 1 I feel sad 2 I am sad all the time and can’t snap out of it 3 I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it 2 0 I am not particularly discouraged about the future 1 I feel discouraged about the future 2 I feel I have nothing to look forward to 3 I feel that the future is hopeless and that things cannot improve 3 0 I do not feel like a failure 1 I feel that I have failed more than the average person 2 As I look back in my life, all can see is a lot of failures 3 I feel that I am a complete failure as a person 4 0 I get as much satisfaction out of things as I used to 1 I don’t enjoy things the way I used to 2 I don’t get real satisfaction out of anything anymore 3 I am dissatisfied or bored with everything 5 0 I don’t feel particularly guilty 1 I feel guilty a good part of the time 2 I feel quite guilty most of the time 3 I feel guilty all of the time 6 0 I don’t feel I am being punished 1 I feel I may be punished 2 I expect to be punished 3 I feel I am being punished 7 0 I don’t feel disappointed in myself 1 I am disappointed in myself 2 I am disgusted with myself 3 I hate myself 8 0 I don’t feel I am any worse than anybody else 1 I am critical of myself for my weakness or mistakes 2 I blame myself all the time for my faults 3 I blame myself for everything bad that happens 9 0 I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself 1 I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out 2 I would like to kill myself 3 I would kill myself if I had the chance 10 0 I don’t cry any more than usual 1 I cry now more than I used to 2 I cry all the time now 3 I used to be able to cry, but now I can’t cry even though I want to 11 0 I am no more irritated now than I ever am 1 I get annoyed or irritated more easily than I used to 2 I feel irritated all the time now 3 I don’t get irritated at all by the things that used to irritate me 12 0 I have not lost interest in other people 1 I am less interested in other people than I used to be 2 I have lost most of my interest in other people 3 I have lost all my interest in other people 13 0 I make decisions about as well as I ever could 1 I put off making decisions more than I used to 2 I have greater difficulty in making decisions than before 3 I can’t make decisions at all anymore 14 0 I don’t feel I look any worse than I used to 1 I am worried that I am looking old or unattractive 2 I feel that there are permanent changes in my appearance that make me look unattractive 3 I believe that I look ugly 15 0 I can work about as well as before 1 It takes an extra effort to get started at doing something 2 I have to push myself very hard to do anything 3 I can’t do any work at all 16 0 I can sleep as well as usual 1 I don’t sleep as well as I used to 2 I wake up 1-2 hours earlier than usual and find it hard to get back to sleep 3 I wake up several hours earlier than I used to and cannot get back to sleep 17 0 I don’t get more tired than usual 1 I get tired more easily than I used to 2 I get tired from doing almost anything 3 I am too tired to do anything 18 0 My appetite is no worse than usual 1 My appetite is not as good as it used to be 2 My appetite is much worse now 3 I have no appetite at all any more 19 0 I haven’t lost much weight, if any, lately 1 I have lost more than 5 lbs (2 kg) 2 I have lost more than 10 lbs (5 kg) 3 I have lost more than 15 lbs (7 kg) (I am purposefully trying to lose weight by eating less. Yes/no). 20 0 I am no more worried about my health than usual 1 I am worried about physical problems such as aches and pains; or upset stomach; or constipation 2 I am worried about physical problems and it’s hard to think of much else 3 I am so worried about my physical problems that I cannot think about anything else 21 0 I have not noticed any recent change in my interest in sex 1 I am less interested in sex than I used to be 2 I am much less interested in sex now 3 I have lost interest in sex completely Score Interpretation 0–5 Normal, not depressed 6–9 High–normal scores may predispose a patient to depression during treatment of a somatic disorder 10–18 Mild to moderate depression 19–29 Moderate to severe depression 30–63 Severe depression From Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch General Psych. 1961;4: 561–571. With permission from copyright © American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch General Psych. 1961;4:561–571. Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Association; 1987. Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Review. 1988;8:77–100. The HAMD scale is used to determine the degree of severity of a depression. The investigator evaluates 17 items. Some knowledge of psychiatry is needed. The scale is widely used. 1. Depressed mood Gloomy attitude; pessimism about the future; feeling of sadness; tendency to weep 0 Absent 1 Sadness 2 Occasional weeping 3 Frequent weeping 4 Extreme symptoms 2. Guilt 0 Absent 1 Self-reproach, feels he/she has let people down 2 Ideas of guilt 3 Present illness is punishment 4 Delusions of guilt 3. Suicide 0 Absent 1 Feels life is not worth living 2 Wishes he/she were dead, or any thoughts of possible death to self 3 Suicide ideas or half-hearted attempt 4 Attempts at suicide (any serious attempt rates 4) 4. Insomnia, initial 0 No difficulty falling asleep 2 Complaints of nightly difficulty in falling asleep 5. Insomnia, middle 0 No difficulty 1 Patient complains of being restless and disturbed during the night 2 Waking during the night—any getting out of bed rates 2 (except voiding bladder) 6. Insomnia, delayed 0 No difficulty 1 Waking in the early hours of the morning but goes back to sleep 2 Unable to fall asleep again if he/she gets out of bed 7. Work and interests 0 No difficulty 1 Thoughts and feelings of incapacity related to activities: work or hobbies 2 Loss of interest in activity-hobbies or work either directly reported by patient or indirectly seen in listlessness, in decisions and vacillation (feels he/she has to push self to work or activities) 3 Decrease in actual time spent in activities or decrease in productivity. In hospital, rate 3 if patient does not spend at least 3 hours a day in activities 4 Stopped working because of present illness. In hospital rate 4 if patient engages in no activities except supervised ward chores 8. Retardation Slowness of thought and speech; impaired ability to concentrate; decreased motor activity 0 Normal speech and thought 1 Slight retardation at interview 2 Obvious retardation at interview 3 Interview difficult 4 Interview impossible 9. Agitation 0 None 1 Fidgetiness 2 Playing with hands, hair, obvious restlessness 3 Moving about; can’t sit still 4 Hand wringing, nail biting, hair pulling, biting of lips, patient is on the run 10. Anxiety, psychic Demonstrated by: subjective tension and irritability, loss of concentration, worrying about minor matters, apprehension, fears expressed without questioning, feelings of panic, feeling jumpy 0 Absent 1 Mild 2 Moderate 3 Severe 4 Incapacitating 11. Anxiety, somatic Physiologic concomitants of anxiety such as: gastrointestinal: dry mouth, wind, indigestion, diarrhea, cramps, belching. Cardiovascular: palpitations, headaches. Respiratory: hyperventilation, sighing, urinary frequency, sweating, giddiness, blurred vision, and tinnitus 0 Absent 1 Mild 2 Moderate 3 Severe 4 Incapacitating 12. Somatic symptoms, gastrointestinal 0 None 1 Loss of appetite but eating without encouragement 2 Difficulty eating without urging. Requests or requires laxation or medication for GI symptoms 13. Somatic symptoms, general 0 None 1 Heaviness in limbs, back, or head; backaches, headaches, muscle aches, loss of energy, fatigability 2 Any clear-cut symptom rates 2 14. Genital symptoms Symptoms such as: loss of libido, menstrual disturbances 0 Absent 1 Mild 2 Severe 15. Hypochondriasis 0 Not present 1 Self-absorption (bodily) 2 Preoccupation with health 3 Strong conviction of some bodily illness 4 Hypochondria delusions 16. Loss of weight Rate either A or B A When rating by history: 0 No weight loss 1 Probable weight loss associated with present illness 2 Definite (according to patient) weight loss B Actual weight changes (weekly): 0 Less than 1 lb (0.5 kg) weight loss in one week 1 1–2 lb (0.5–1.0 kg) weight loss in week 2 Greater than 2 lb (1 kg) weight loss in week 3 Not assessed 17. Insight 0 Acknowledges being depressed and ill 1 Acknowledges illness but attributes cause to bad food, overwork, virus, need for rest, etc. 2 Denies being ill at all From Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. The SDS is a 20-item questionnaire for the assessment of depressive symptoms. Three items evaluate gastroenteric symptoms of depression (i.e. decrease of appetite, weight loss, and constipation). A score of > 40 is high. Responses 1. None, or a little 2. Some of the time 3. Good part of the time 4. Most of the time 1. I feel down-hearted, blue, and sad

Introduction

Aspects of Validity

Aspects of Reliability

Bias

(A) Global Generic QoL Assessments

Health Status: The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36 Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)

Aims

Comments

References

Health Status: the MOS24 Short Form Health Survey (SF-24)

References

SF-12

References

Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI)

References

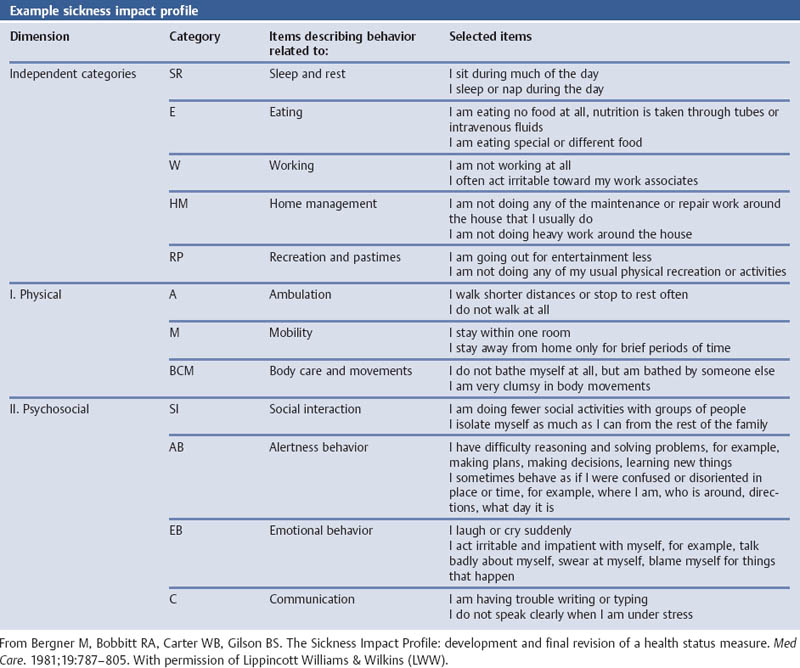

Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)

References

World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-100)

References

WHOQOL-BREF

References

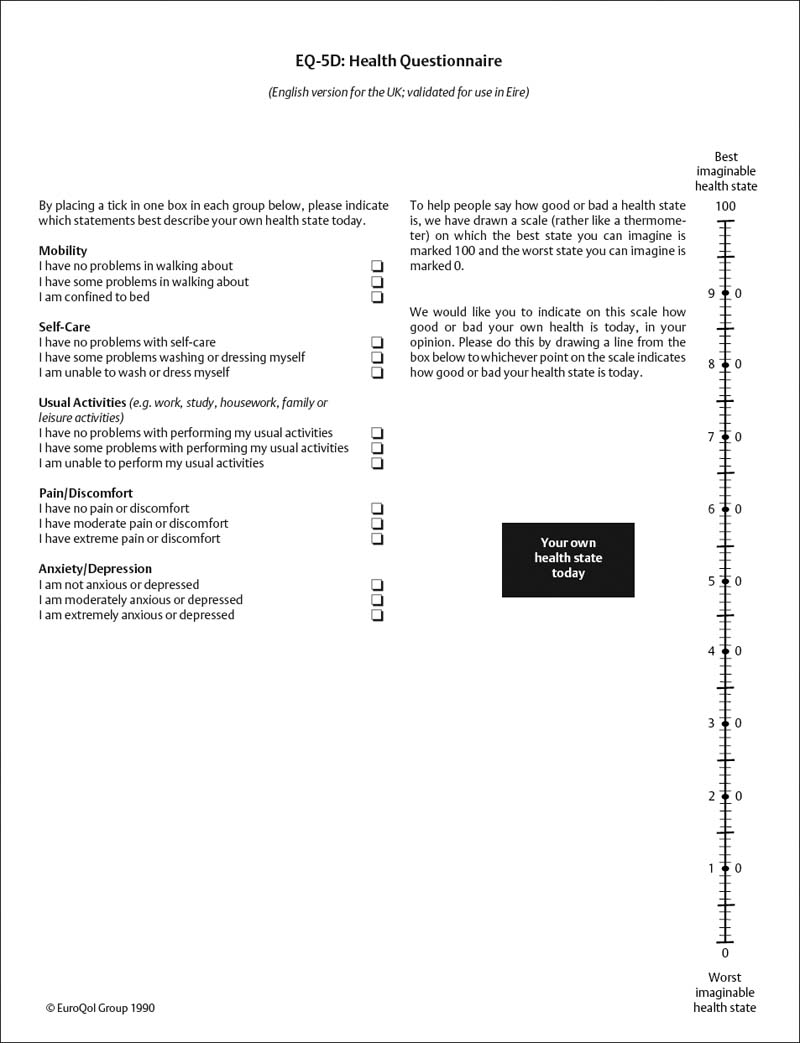

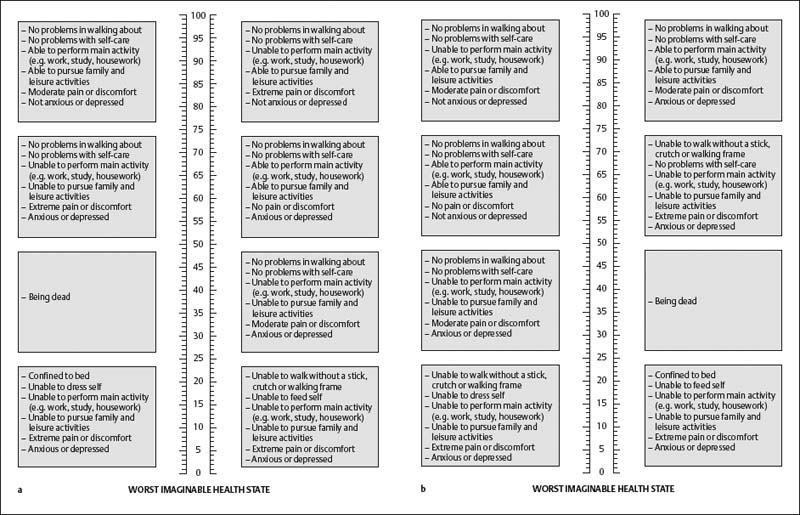

EUROQol Instrument (EQ-5D)

EQ-5D Self-Classifier and EQ VAS Score

EQ Index

References

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)

References

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) According to Goldberg

References

Impact on Daily Activity Scale (IDAS)

References

Clinical Global Impression: Global Improvement Scale (CGI)

References

Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB)

References

Illness Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ)

References

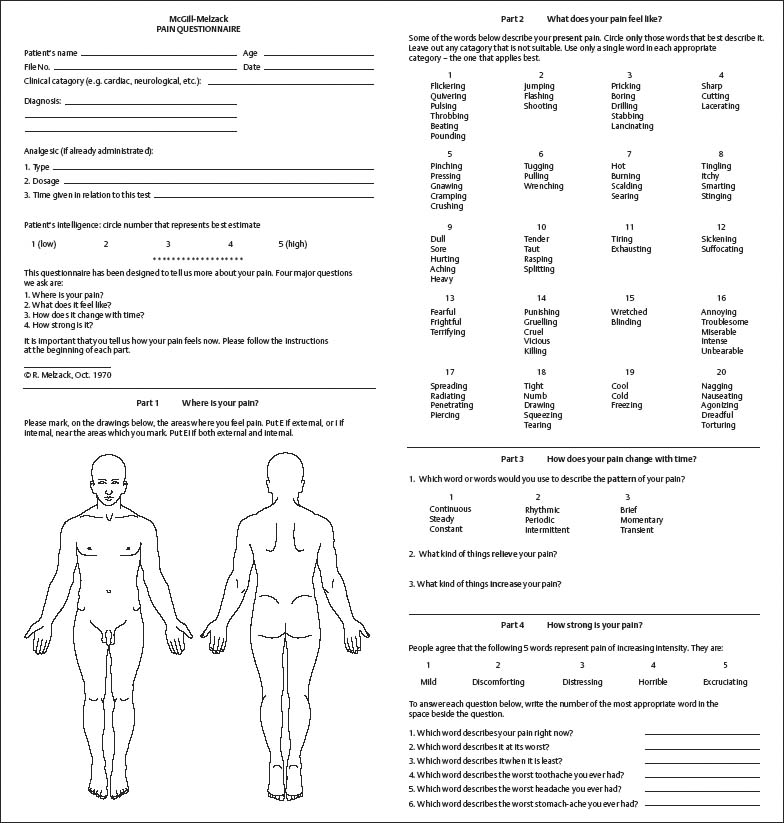

The McGill Pain Questionnaire

References

Sheehan’s Disability Scale (DISS)

References

Symptoms Check List 90 (SCL-90)

References

Global Severity Index (GSI)

References

Complaint Score Questionnaire (CSQ)

Göteborg Quality of Life Instrument

References

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) (HADS)

Anxiety Questions of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

References

Anxiety and Depression Scaling According to Goldberg

References

The Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

References

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Score

References

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

References

Hamilton Psychiatric Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)(HAMD)

References

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access