Examination of the Patient

Because you are familiar with examining patients, this chapter is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather to orient you to the essential components of examining a patient with digestive complaints.

The physician should be sensitive to the patient’s physical and emotional comfort. Is the patient in as comfortable a position as possible? Is the patient warm enough? Have you ensured the patient’s privacy by closing doors and adjusting drapes? How does the patient feel about others in the room—colleagues, residents, students? Saying “This may be a little awkward or embarrassing for you” may reassure and relax the patient. As you conduct the examination, you should inform the patient of what you intend to do, particularly with regard to aspects of the examination that may be sensitive and embarrassing.

I. THE GENERAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION.

The physical examination of a patient with digestive complaints is not limited to the abdomen, although the abdominal examination is important. A general physical examination, including determination of vital signs, is indicated during the initial evaluation. In particular, is there pallor of the nail beds or conjunctivae? Is the tongue of normal color and texture? Is there any lymphadenopathy? What about changes in the color or texture of the skin? Is edema evident? Although abnormalities of the heart, lungs, or other organ systems may not be related directly to the patient’s digestive complaints, they may be important considerations in the subsequent management of the patient.

II. THE ABDOMINAL EXAMINATION.

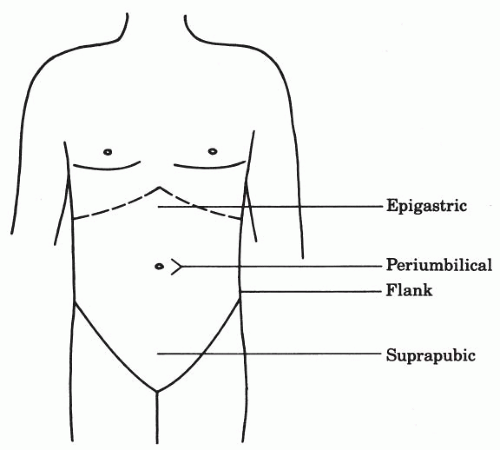

The abdomen conventionally is divided into four quadrants: right upper, left upper, right lower, and left lower. It is also common, however, to refer to areas of the abdomen by more specific terms, such as epigastric, periumbilical, suprapubic, and right or left flank (Fig. 3-1).

A. Patient position.

The patient should lie in a supine position, although the head may be elevated slightly for comfort. Some patients lift their arms over their heads, which tightens the abdominal wall and makes palpation and interpretation of signs of peritoneal irritation difficult. The arms should remain at the patient’s side. Flexion of the knees also may relieve abdominal tightness.

B. Inspection

1. Skin of the abdomen.

Are there any scars, dilated veins, rashes, or other marks?

2. Is the umbilicus normal?

Is there an umbilical or abdominal wall hernia?

3. Contour of the abdomen.

Is the abdomen protuberant or concave? Are there any bulges?

4. Can you see peristaltic movements or pulsations?

C. Auscultation.

In examining the abdomen, it is probably wise to listen before performing percussion and palpation because these maneuvers may alter the quality of bowel sounds.

1. Bowel sounds.

What is the character of the bowel sounds? In healthy people, the character and frequency of bowel sounds vary widely. In people who are hungry, bowel sounds may be active, whereas after a meal the abdomen typically becomes rather quiet. Bowel sounds may be increased in frequency and intensity in diarrheal conditions. Intestinal obstruction is characterized initially by increased bowel sounds that progress to high-pitched tinkling sounds and rushes. On the other hand, bowel sounds become decreased or absent in conditions that cause paralytic ileus, such as peritonitis or electrolyte imbalance.

2. Other abdominal sounds.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree