Anorectal Abscess

Brett E. Ruffo

Staphylococcus Aureus By Gram and Koch he swore He would invade new regions Unconquered heretofore— By Gram and Koch he swore it, To take a patient’s life, And called the Cocci, young and old, From all his colonies of gold To aid him in the strife

St. Bartholomew’s Hospital Journal 1909;17:13 —“THE BATTLE OF FURUNCULUS”

▶ ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Anorectal abscess is an acute inflammatory process that often is the initial manifestation of an underlying anal fistula. An abscess in this area may also be a consequence of other causes and associations. These include the following:

Foreign body intrusion

Trauma

Malignancy

Radiation

Immunocompromised state (e.g., leukemia, AIDS)

Infectious dermatitides (e.g., suppurative hidradenitis)

Tuberculosis

Actinomycosis

Crohn’s disease

Additionally, anorectal abscess may develop as a complication of anal operations, such as hemorrhoidectomy (rarely—see Chapter 11) and internal anal sphincterotomy (see Chapter 12).

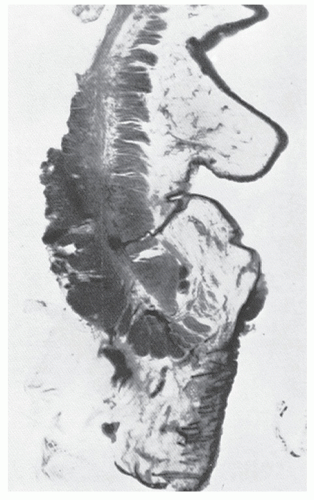

The cause of nonspecific anorectal abscess and fistula is believed to be plugging of the anal ducts; this is known as the cryptoglandular theory. Credit for introducing the concept of gland infection in the pathogenesis of anal fistula is generally attributed to Chiari (1878)17 and to Herrmann and Desfosses (1880).38 Klosterhalfen and colleagues examined 62 autopsy specimens by means of conventional and special immunohistologic staining methods and confirmed that anal intramuscular glands should be the anatomic correlate of anal fistulas.46 Between 6 and 10 of these glands and ducts are located around the anal canal and enter at the base of the crypts (see Figure 11-2). Parks (see Biography, Chapter 29) demonstrated by meticulous histologic review that one-half of all crypts are not entered by glands, that the ducts usually end blindly, and that the most common direction of spread is downward into the submucosa.63 Of particular interest is his observation that in two-thirds of the specimens, one or more branches enter the sphincter, and in one-half, the branches cross the internal sphincter completely to end in the longitudinal layer (Figure 13-1). In his study, however, no branches crossed into the external sphincter. The implication is that plugging or infection of the duct can result in an abscess that can spread in several directions. This may ultimately lead to the development of an anal fistula. In theory, therefore, an intersphincteric fistula may develop when the duct traverses the internal sphincter, and a transsphincteric fistula may be a consequence of the duct traversing the external sphincter.

Shafer and colleagues performed surgery for anal fistula in 52 infants and noted a markedly irregular, thickened dentate line.78 They attributed the condition to a defect in the dorsal portion of the cloacal membrane, which fuses with the hindgut during week 7 of gestation. In essence, then, contemporary theory implies that fistula-in-ano is the result of a congenital anomaly or a predisposition.20

Further support for the proposition of a congenital origin, albeit by different mechanisms, has been offered by several authors. One theory holds that an excess of androgens may lead to the formation of abnormal glands in utero and that these abnormal glands are predisposed to infection.27 Pople and Ralphs postulated that the “inappropriate” presence of columnar and transitional epithelium along the length of the excised fistula tracts of four infants is further evidence of a congenital abnormality presenting in the first few months of life.68 They suggest that migratory cells from the urogenital sinus of the primitive hindgut become locally displaced and entrapped. Because fusion in females is less extensive, this could explain, according to the authors, the higher incidence of fistula in males.

▶ AGE, SEX, AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Abscess and fistula occur more commonly in men than in women. McElwain and colleagues reported a ratio of three men to one woman, whereas two large series from Cook County Hospital in Chicago were noted to have a two-to-one ratio.58,70,71 At the time of presentation, two-thirds of patients are in the third or fourth decade of life.58,70 There seems to be a seasonal occurrence for the condition, with the highest incidence in the spring and summer. Despite the opinions of some, there does not appear to be a correlation between the development of anal abscess and personal hygiene or bowel habits, such as diarrhea.89

Hill reported a personal experience of 626 patients40; the youngest was 2 months of age, and the oldest was 79 years. The number of male patients was almost twice the number of females. In his experience, most developed symptoms in the fourth, fifth, and sixth decades.

Infants younger than 2 years of age represent a different spectrum of the disease when compared with older children and adults. There is an overwhelming male predominance with abscess and with concomitant anal fistula, that is, in excess of 85%.1,46,67 However, the distribution in older children tends to resemble that seen in adults.

▶ TYPES OF ABSCESS

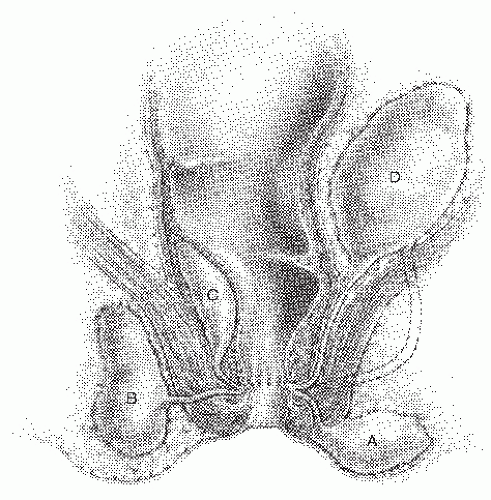

Four presentations of anorectal abscess have been described:

Perianal

Ischiorectal

Intersphincteric (also known as submucosal)

Supralevator

These types are illustrated in Figure 13-2. It is important to distinguish among these presentations because the etiology, therapy, and implications for the presence or subsequent development of anal fistula are different for each.

Perianal Abscess

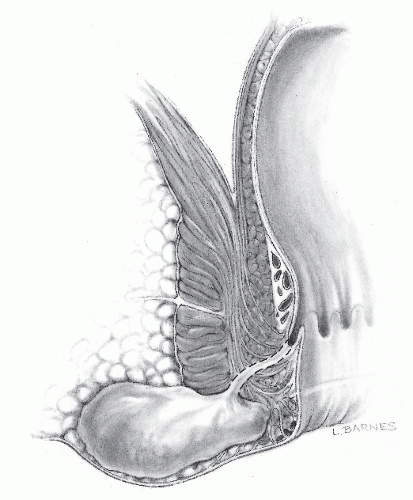

Perianal (or perirectal) abscess is identified as a superficial, tender mass outside the anal verge (Figure 13-3). It is arguably the most common type of anorectal abscess, occurring in perhaps 40% to as much as 60% of cases, but the relatively high incidence may be a reflection of the nature of one’s practice. The patient can present with a short history of

painful swelling that may be exacerbated by defecation and by sitting. Not uncommonly, however, one may complain of a recurrent lump that resolves or drains spontaneously. A history of having undergone a prior incision and drainage is not unusual. Fever and leukocytosis are rare.

painful swelling that may be exacerbated by defecation and by sitting. Not uncommonly, however, one may complain of a recurrent lump that resolves or drains spontaneously. A history of having undergone a prior incision and drainage is not unusual. Fever and leukocytosis are rare.

FIGURE 13-2. Infection of the anal duct can present as an abscess in a number of locations. A: Perianal. B: Ischiorectal. C: Intersphincteric. D: Supralevator. |

FIGURE 13-3. Perianal abscess. Only a few of these lesions are associated with an underlying fistula. The dashed lines illustrate the possible course of a fistula tract if it is present. |

Physical examination reveals an area of erythema, induration, or possibly fluctuance. Proctosigmoidoscopic examination may be difficult to perform because of pain, but even when it can be accomplished, it is usually unrewarding. Occasionally, however, anoscopic examination demonstrates pus exuding from the base of a crypt or at the site of a chronic anal fissure.

Treatment

As mentioned in other chapters, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) has established guidelines for the treatment of numerous conditions. These include the parameters for the management of abscess and anal fistula.81

Acute Suppuration (Abscess)

Presentation and Management

An abscess should be drained in a timely manner; lack of fluctuance is not a reason for delay in treatment. If the abscess is superficial, it may be drained in the office setting using a local anesthetic. If the patient is too tender to permit examination and drainage, then these measures should be undertaken in the operating room. Antibiotics may have a role as adjunctive therapy in special circumstances, including certain heart valve conditions, immunosuppression, extensive cellulitis, and diabetes. Laboratory tests are usually not required unless the patient harbors systemic symptoms. Further evaluation by means of endoanal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is unnecessary except perhaps when the etiology of the patient’s symptoms is in question. Location of the abscess should be documented. If possible, anoscopy should be performed to reveal the primary site of infection. Patients should notify the physician if pain recurs after abscess drainage.

It is important to distinguish an anal abscess from other pathologic entities, such as hidradenitis, skin furuncles, herpes, HIV, tuberculosis, syphilis, and actinomycosis.19 One must always be cognizant of the fact that thickened skin tags, multiple fissures, eccentric location of a fissure, or concomitant fistula may suggest Crohn’s disease. Any suspicion requires a more comprehensive workup than might otherwise be indicated (see later). When only erythema is present with no apparent mass, the surgeon may be misled into believing that incision and drainage will not be beneficial. Under such circumstances, the patient may be instructed to take sitz baths or may be given a broad-spectrum antibiotic and advised to return in 24 to 48 hours. Despite the absence of fluctuance or significant induration, an abscess is usually present. A patient who is dismissed without undergoing drainage may return a few hours or days later, distressed that spontaneous discharge has taken place, even though the discomfort may have been ameliorated. There is no place for antibiotics alone in the management of anorectal abscess. As I. J. Kodner has stated in numerous panel discussions on the subject, “The presence of pain suggests the need to drain.”

The procedure is usually readily performed in the office with a local anesthetic. Alternatively, an emergency department setting or ambulatory surgical facility may be preferred. A large-bore hypodermic needle inserted into the region of induration is a simple diagnostic test, but establishing adequate drainage is critical to success. If purulence is present, a small incision is made using a local anesthetic. The pus is drained; a small gauze wick, gauze, or drain may be inserted, depending on the surgeon’s personal preference; and a dressing is applied. Aggressive manipulation and breaking of loculations is not only unnecessary but may also risk sphincter injury. The patient is instructed to remove the dressing and the drain in 24 hours while taking a warm bath. Baths three times daily are advised, and the patient is reexamined in 7 to 10 days. Replacing the wick, drain, or packing (if it had been placed previously) is not necessary. At this time, proctosigmoidoscopic and anoscopic examinations are performed. If an external opening persists and a fistula tract is identified, a definitive procedure is indicated (see Chapter 14, “Anal Fistula”).

Postoperative Antibiotics

The value of postoperative antibiotics for someone who has undergone incision and drainage is open to question. However, those at an increased risk based on the criteria outlined in Chapter 5 should be treated.

Antibiotics given after drainage of a perianal abscess have been an issue of debate for some time. Sözener and colleagues undertook a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter study in order to determine whether antibiotics are important in preventing the subsequent development of an anal fistula after initial drainage of an anal abscess.80 A total of 151 patients were analyzed; 76 received antibiotics and 75 did not. Those with prior anorectal surgery,

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), recent antimicrobial use, recurrent abscess, pregnant, or who were immunocompromised were excluded. No preoperative antibiotic was given. Augmentin 875 mg was given twice daily for 10 days, and the controls were given similar pills without content. Blinding was applicable to both staff surgeon and research assistants. A follow-up at 1 year revealed that a fistula developed in almost 30% (45 of 151). Fistula development was found in 22.4% of those treated with the placebo and in 37.3% in the antibiotic-treated group. Their conclusion was that antibiotics had no protective or effective means of decreasing the rate of fistula formation and may actually increase the incidence after first-time drainage of an anal abscess.80

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), recent antimicrobial use, recurrent abscess, pregnant, or who were immunocompromised were excluded. No preoperative antibiotic was given. Augmentin 875 mg was given twice daily for 10 days, and the controls were given similar pills without content. Blinding was applicable to both staff surgeon and research assistants. A follow-up at 1 year revealed that a fistula developed in almost 30% (45 of 151). Fistula development was found in 22.4% of those treated with the placebo and in 37.3% in the antibiotic-treated group. Their conclusion was that antibiotics had no protective or effective means of decreasing the rate of fistula formation and may actually increase the incidence after first-time drainage of an anal abscess.80

Drainage has been shown to be the most important aspect in the treatment regimen for anal abscess. Although antibiotics may be beneficial for those with more severe illnesses such as IBD, HIV, and those with an associated cellulitis, for the straightforward anal abscess, incision and drainage is considered appropriate as the sole treatment.

Microbiology

The purpose of culturing the pus following drainage of a perianal or ischiorectal abscess is also a subject of some interest. Usually, the physician performs a culture to determine the appropriate antibiotic for treatment. As previously mentioned, however, antibiotics are usually unnecessary, but culture does have some benefit in determining the likelihood for the subsequent development of a fistula. If the culture demonstrates no bowel-derived organisms (i.e., skin bacteria), the chance of a subsequent fistula is virtually nil.31,37 Conversely, if enteric organisms are identified, the probability of the presence of a fistula is increased. Lunniss and Phillips, in a prospective trial involving 22 patients, found culture of gut organisms to be quite sensitive for detecting an underlying fistula, but not particularly specific (80%).53 Conversely, when an infection was present in the anorectal space, culture was 100% sensitive and 100% specific for the detection of an underlying fistula. Certainly, in this group of patients, surgical assessment is a better predictor of the subsequent development or presence of a fistula than is culture.

The increased incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), especially in hospital populations, may lead to an increased frequency of the surgeon obtaining wound cultures. The question, however, is whether such colonization mandates antibiotics against MRSA simply because the organism is present in the culture. Conversely, should the presence of systemic signs and symptoms dictate antibiotic management? The answer today: surgeon’s judgment.

The study of the bacteriology of perirectal abscess in children, as in adults, has demonstrated that anaerobic organisms are the predominant isolates, although S. aureus is frequently found.11,48 Although no studies have been performed in children concerning the implication of the different culture results, it is reasonable to assume that the principle is identical.

A recent study by Liu and coworkers reviewed the microbiology of 183 patients, both diabetic and nondiabetic.52 The purpose was to identify the most common organism involved in perianal abscess. In nondiabetics, most commonly identified was Escherichia coli, whereas Klebsiella pneumoniae was found to be the dominant organism. The authors also noted that first-generation cephalosporins will eradicate Klebsiella in 90% of cases.52

As implied, culturing will likely benefit those who have recurrent or nonresolving abscesses. However, colonization is one possible factor; true infection with the organism is a different issue altogether. In a review of S. aureus by Tong and associates, it was difficult to determine the most appropriate course of treatment because multiple factors contribute to actual infection.86 There are numerous concomitant variables, such as host factors, immune status, skin barrier concerns, age, comorbidities, and health care contact. Another important concern is the emergence of resistance to antibiotics; there is, therefore, a downside to treating asymptomatic colonization. Albright and colleagues suggest culturing all perianal abscesses with extensive erythema, cellulitis, and lack of purulent material because such findings are more likely related to MRSA.2

Stelzmueller and coworkers found, in a retrospective review of perianal infections, that group milleri streptococci (GMS), a heterogeneous group of bacteria, was involved in more deep, complex, and recurrent abscesses.82 Polymicrobial infections with E. coli and Bacteroides fragilis remained the most common pathogens. These patients needed more intensive surgical therapy and an increased requirement for antibiotics in their experience.82

Another study by Ulug and associates found that aerobic bacteria played the major role in the etiology in 81 patients, the following being the most common: Escherichia coli, Bacteroides species, Enterococcus species, and skinderived organisms, such as coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. aureus, and Peptostreptococcus.87 They supported the concept that antibiotics should be used only in selected cases with drainage but did recommend routine wound culture because of increasing emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and their varying virulent factors.87

Practice parameters by the ASCRS advise those with bacterial endocarditis, prosthetic heart valves, congenital heart disease, or a heart transplant should all receive preoperative antibiotics prior to drainage. There is no longer evidence to support preoperative antibiotics in patients with mitral valve prolapse.10

Recurrence

The incidence of recurrence of perianal abscess or fistula development after initial drainage is approximately 35%. Determining the risk factors that predispose to these consequences has been somewhat controversial.

Hamadani and coworkers looked at recurrence of an abscess or development of a fistula following treatment for firsttime perianal abscess in a retrospective study of 148 patients.33 Age younger than 40 years was the single most important factor related to an increased recurrence risk in a 38-month follow-up. The peak incidence of developing an abscess was age older than 40, however, but recurrence was twofold higher in patients younger than 40. Those with HIV, IBD, recurrent abscesses or fistulas, and inadequate follow-up were excluded. Smoking, gender, and antibiotics did not seem to be a relevant issue. It was noted that diabetes may actually be “protective” against subsequent fistula development. In this study, gender, although not relevant to development of a fistula or abscess recurrence, revealed a 71% predominance in males.

Yano and associates attempted to determine the factors that may lead to recurrence of an anal abscess following drainage in 205 first-time patients followed during 5 years, excluding those with prior abscess, fistula, anorectal surgery,

and IBD.95 Parameters included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), type of anesthesia, location of abscess, anatomic classifications, drain usage, presence of diabetes, and time to drainage after symptoms developed (early was within 7 days and late was after 8 days). A total of 74 patients developed a recurrence. The only significant factor associated with recurrence was the timing from the development of symptoms to subsequent abscess drainage. Those with early drainage had a lower rate of recurrence.

and IBD.95 Parameters included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), type of anesthesia, location of abscess, anatomic classifications, drain usage, presence of diabetes, and time to drainage after symptoms developed (early was within 7 days and late was after 8 days). A total of 74 patients developed a recurrence. The only significant factor associated with recurrence was the timing from the development of symptoms to subsequent abscess drainage. Those with early drainage had a lower rate of recurrence.

It has been shown that men are two to four times more likely to develop a fistula after an abscess. In a recent study in San Diego at the Veterans Administration health care system, it was proposed that a history of recent smoking is a risk factor in developing an anal fistula after drainage of an anal abscess.19 A case-controlled study was initiated using a tobacco questionnaire. Three disease processes were excluded: diabetes, IBD, and HIV. Recent smokers were defined as currently smoking or those who quit within the previous year. These were compared with nonsmokers and former smokers. Seventy-four abscess/fistula cases were identified along with 816 controls. There were 22 nonsmokers, 24 current smokers, and 28 previous smokers (12 quit within a year, 27 within 5 years, and 28 within 10 years). Those who smoke or who quit within a year had the highest incidence of developing an anal fistula. Almost a twofold higher risk was noted, an increased association with smoking lasting up to 5 years of quitting. The 5-year mark appears important because after that date, the risk appear to be that of nonsmokers. Limitations to the study are selection bias, definitions of smoking, recall bias, and a nonstandardized questionnaire used to obtain the data. But this publication does demonstrate a strong correlation between smoking and the subsequent development of recurrent abscess and anal fistula. This conclusion should inspire additional research.19 In an editorial by Zimmerman regarding this study, educating patients on the importance of cessation of smoking was felt to be an obvious health care benefit that may offer this additional advantage.96

Synchronous Fistulotomy

A fistula with an internal opening may be seen at the time that the abscess is drained. The incidence as reported from numerous centers is somewhat variable. This may be attributed to the differences in aggressiveness of examiners in attempting to identify a fistula and perhaps also to demographic factors. Vasilevsky and Gordon reported recurrent abscess or the development of an anal fistula in 48% of patients who underwent drainage of a perianal or ischiorectal abscess.89 Table 13-1 illustrates the results from the Cook County Hospital with the various types of fistulas.

TABLE 13-1 Incidence of Fistula in Various Types of Anorectal Abscess | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If the internal opening is low lying, the surgeon may elect to perform fistulotomy at the same time the abscess is drained in order to avoid the need for a second procedure. However, the literature is rather contradictory on this point because it is not always clear from the article what type of fistula or abscess the author is treating. A recurrence rate of a mere 3.4% was reported by McElwain and colleagues following initial drainage and fistulotomy, but this is old data.57 Their subsequent report demonstrated the rate of recurrence of abscess, fistula, or both to be 3.6%, which compared quite favorably with their own recurrence rate of 6% when an established fistula was excised.58 Waggener also recommends primary fistulotomy.90

Scoma and coworkers reported a retrospective review of 232 patients with anal abscess who underwent initial office drainage only.76 A fistula subsequently developed in twothirds. Unfortunately, the authors failed to breakdown the incidence of fistula according to the type of abscess. They recommended that fistulotomy be delayed until the fistula becomes manifest. Others concur, although it is not always clear whether a vigorous attempt was made to identify a fistula at the initial procedure.34 Tang and associates compared incision and drainage alone with concurrent fistulotomy for perianal abscess with a demonstrated internal opening in a prospective, randomized study involving 45 patients.85 They concluded that incision with drainage alone was not associated with a statistically significantly higher incidence of recurrence of anal fistula when compared with concomitant fistulotomy. Therefore, a simple drainage procedure was essentially as good as a definitive fistula operation.

With respect to incontinence, Stremitzer and colleagues reviewed 173 patients over a 121-month follow-up period.83 If synchronous fistulotomy were performed, severe incontinence developed in 4% and mild in 9%, with a higher rate of incontinence noted in those with multiple procedures.

In a review by Holzheimer and Siebeck of 63 studies from 1964 to 2004, there were no data that effectively compared the different available treatment options.41 Many flaws were found in the randomization of, especially that of definitions, abscess type and management approach. Their conclusion was that neither primary nor secondary fistulotomy could be recommended based on the reviewed data. One must rely on the experience of the surgeon to adequately evaluate each individual situation in order to determine the appropriate management strategy.41

In a review by Holzheimer and Siebeck of 63 studies from 1964 to 2004, there were no data that effectively compared the different available treatment options.41 Many flaws were found in the randomization of, especially that of definitions, abscess type and management approach. Their conclusion was that neither primary nor secondary fistulotomy could be recommended based on the reviewed data. One must rely on the experience of the surgeon to adequately evaluate each individual situation in order to determine the appropriate management strategy.41

This subject was also studied by Malik and colleagues in a Cochrane database review in which data from six randomized trials were analyzed from 1997 to 2008.55 The concern was that synchronous fistulotomy may either lead to increased incontinence or subject the patient to unnecessary surgery because some abscesses will probably resolve spontaneously. Of the 479 patients included, there was no statistically significant increased incidence of incontinence reported within 1-year follow-up of drainage and synchronous fistulotomy. There was, however, a slight increase in incontinence with transsphincteric, high, and complex fistulas. This review concluded that the data is “weak,” concerning any increased incontinence risk with fistula surgery at the time of initial abscess drainage. Emphasized again is the need for sound surgical judgment in order to help ensure appropriate selection of those who will benefit from this approach and those who need another alternative. Their conclusion is that a concomitant fistulotomy should be considered, but only in carefully selected patients.55

If the sphincter anatomy is unclear, loose seton drainage is always safe with essentially no risk of incontinence unless aggressive manipulation of loculations is performed. Stremitzer and associates recommend referral to a surgeon who has experience in managing these potentially complicated entities in order to minimize recurrence, ongoing sepsis, and to limit incontinence.83 They also emphasize the importance of supervising and educating residents because they are often the initial contacts for the patient.83

Opinion

In my own experience, an anal fistula is usually not recognized at the time of drainage of a perianal abscess. However, if a low-lying fistula is encountered, I recommend incision of the tract if it can be easily accomplished at that time. In accordance with my own preference, the patient usually undergoes drainage as an office procedure. Therefore, discomfort often precludes a more thorough evaluation, the identification of a fistula tract (if present), and the ability to perform definitive fistulotomy. Certainly, if an individual is to undergo a regional or general anesthetic, concomitant fistulotomy is a reasonable plan, recognizing that the use of setons is prudent if there is any uncertainty as to sphincteric anatomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree