Fig. 1

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Muscle thickening is indicated by arrows. A antrum of the stomach with retained fluid

Small Bowel

Conventional radiographs, upper GI series, and US are the initial imaging modalities in children with abdominal pain or obstruction [3]. MR enterography may serve as a problem solver in older children. The most important additional value of US over conventional abdominal radiographs in these children is the capability to visualize peristalsis, vascularity, bowel wall characteristics, dilatation of fluid-filled loops, and extraintestinal abnormalities, e.g., ascites and other fluids. The jejunum and ileum can be distinguished from the colon based on its anatomical location, caliber, contents, folds, and peristalsis.

Anatomical Location. The colon has a peripheral location in which the ascending and descending colon lie dorsally in both flanks and the transverse colon is located ventrally in the upper abdomen. The sigmoid colon traverses the left psoas muscle and courses into the pelvis. In contrast, the small bowel has a more central position.

Caliber. The diameter of the small bowel is small, and that of the large bowel is relatively large (explains the nomenclature).

Contents. The small bowel is either empty or filled with liquid contents and little air, whereas the colon is generally filled with gas-filled bulky stools.

Folds. Folds in the jejunum are more numerous, thinner, and closer together than the ileal folds. In the terminal ileum, the mucosa may be thickened due to hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue. The colon is recognized by its haustrations. Infants have little to no haustrations.

Peristalsis. The small bowel is continuously moving due to peristaltic waves, whereas the colon shows sparse movements. In general, thickened small-bowel loops show decreased peristalsis and contain little air and are therefore easily visualized and measured. At least three patterns can be distinguished [10]:

Stratified thickening of small bowel is found in infectious ileitis, advanced appendicitis, early Crohn’s disease, and graft-versus-host disease

Nonstratified thickening of the small bowel is found in HSP, advanced Crohn’s disease, tuberculous ileitis, protein- loosing enteropathy, hereditary angioedema, ischemia, celiac disease, Burkitt lymphoma, Kawasaki’s disease, and viral enteritis

Nonstratified thickening with hyperplastic valvular folds is found in viral (and sometimes bacterial) lymphoid hyperplasia and Yersinia ileitis.

Malrotation and Midgut Volvulus

This entity is discussed separately in the Kangaroo section of this syllabus (pp. 279–288).

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic IBD characterized by its granulomatous component, its transmural inflammation, its tendency to affect the surrounding tissues, and its formation of fistula and sinus tracts. The exact cause is still unknown. It can occur in children from the age of 5 years, but most often, adolescents and young adults are affected. The initial course is insidious, with recurrent diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Also, atypical features such as growth failure, malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, amenorrhea, arthritis, and cutaneous and ocular manifestations may be present. Levels of calprotectin in stools are increased. Calprotectin is a neutrophil protein that is released from activated leukocytes [11].

Crohn’s disease can affect the entire digestive tract but has a predilection for the terminal ileum. Initially, the inflammation starts as aphthoid ulcers in the mucosa and progresses to a transmural inflammation that eventually also involves the surrounding fat. Finally the inflammation may proceed to other surrounding structures, such as skin, other bowel loops, and urine bladder, forming sinus tracts and fistula and even abscesses. Diagnosis depends on US and MR enterography. US is of great value in diagnosis and follow-up in children with IBD [12, 13], with a sensitivity of 75–88% and a specificity of 82–93% [14–16]. Faure even reports a sensitivity of 100% for terminal ileitis in Crohn’s disease [14]. On US, initially, bowel wall stratification is preserved. In advanced disease, stratification is lost, and the affected bowel loop is surrounded by thickened, inflamed, echogenic fat, more or less isolated from the other bowel loops (Fig. 2). Close attention should be paid to small hypoechoic spurs that extend into the echogenic fat. They probably represent an insidious sinus tract and predict future fistula or abscess formation.

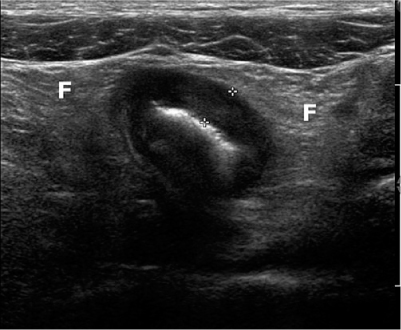

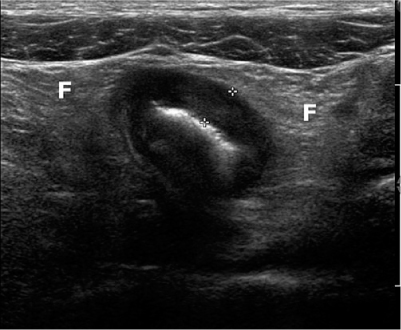

Fig. 2

Advanced Crohn’s disease with loss of stratification and with wall thickening (5 mm, between calipers) and thickened surrounding echogenic fat (F)

Intestinal Polyps

Intestinal polyps in the small bowel are usually hamartomatous polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. They occur more often in the jejunum than in the ileum. US is able to detect moderate and large polyps and therefore may serve as a screening method for detecting uncomplicated polyps. However, one should take into account the high specificity but relatively low sensitivity. US is valuable in diagnosing complications associated with small-bowel polyps, e.g., intussusceptions [3]. One must be aware that specific particles within stools (e.g., undigested food, foreign bodies) may mimic polyps.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) is a systemic vasculitis of unknown cause involving the small vessels of the skin, gut, and kidneys. Mean age of presentation is approximately between 3 and 8 years, with a slight male predominance [17–19]. Patients develop a typical skin rash and intestinal complaints such as abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and melena or bloody stools. Proteinuria, hematuria, and arthralgia are additional findings. Abdominal complaints are present in two thirds of the patients and may be severe. Intestinal symptoms may precede the skin rash, and therefore, the radiologist may be the first to suggest the diagnosis. The small bowel is affected, including the duodenum [20]. Involvement is frequently multifocal, with skipped lesions. US findings include symmetrical thickening of the bowel wall up to 11 mm, loss of stratification, intramural hematoma, enlargement and smoothening of folds, hypoperistalsis, hyperemia, lymphadenopathy, and often, some clear peritoneal fluid. These US findings can subside within several days and exacerbations and remissions may occur. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive value of US for gastrointestinal involvement of HSP is 83%, 100%, 100%, and 54%, respectively [21]. Complications include pathological small-bowel intussusception (PSBI), bleeding, and rarely, necrosis and perforation, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and appendicitis. It is a self-limiting disease, although persisting proteinuria due to nephritis is a well-known complication.

Ascaris Lumbricoides

Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common helminthic infestation world wide, mainly affecting children and young adults. Many children are asymptomatic or have minor nonspecific abdominal complaints. US images are quite characteristic depending on the image plane: in the longitudinal plane, the worms appear as parallel echogenic lines; in transverse images, they appear as round dots inside the lumen. Fluid administration prior to the examination improves visualization of the worms. Differentiation with intraluminal lines may be difficult, and worm movement can aid in differentiation; tubes and lines do not move by themselves. Ascaris residing in the small intestines may migrate into the biliary system, pancreatic duct, and appendix, causing symptoms of biliary stones, pancreatitis, or appendicitis [22].

Meckel’s Diverticulum, Ileocolic Intussusception, and Necrotizing Enterocolitis

These entities are also discussed separately in the Kangaroo section of this syllabus (pp. 279–288).

Intestinal Duplication Cysts

Intestinal duplication cysts can occur anywhere along the alimentary tract, but the most common location is the ileum. Therefore, these cysts are discussed in this smallbowel section. Duplication cysts are spherical or tubular masses adherent to the GI tract, which sometimes communicate with it [23–25]. They are lined with intestinal epithelium, and there is smooth muscle within the wall. In 15–20% of cases, the cyst contains gastric mucosa that may cause hemorrhages. The most common site is the ileum, followed by the stomach. Most patients present within the first year of life, with symptoms including GI obstruction; less common presentations include a palpable mass, intussusception, hemorrhage, and abdominal distension. US and MRI readily appreciate the cystic nature of duplication cysts. The content is often anechoic but may contain debris after hemorrhage or due to mucoid material. Rarely, the cyst appears completely hyperechoic after hemorrhage. Two US signs are virtually diagnostic of a duplication cyst: first is the double-layer demonstration of its wall, consisting of echogenic mucosa and hypoechoic muscularis propria, the so-called “gut signature” (Fig. 3). Second is the demonstration of peristalsis in the cyst. Moreover, meticulous US examination may identify the primary bowel loop from which the cyst originates; the cyst shares the muscularis propria and serosa with the primary bowel loop. Ovarian, urachus and mesenteric cysts and lymphatic malformations can mimic duplication cysts.

Benign Small-Bowel Intussusception

Benign small-bowel intussusception (BSBI) is a recently described entity and differs from the classic symptomatic ileocolic intussusception; BSBI occurs predominantly in the right lower quadrant or periumbilical region, has a smaller diameter than pathological (ileocolic) intussusceptions (mean 1.4 cm versus 2.5 cm), a small length (mean 2.5 cm), a thinner outer rim, and does not contain mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 4) [26, 27]; moreover, peristalsis in the intussuscepted loop persists, in contrast with ileocolic intussusceptions. Often, BSBI is an incidental finding, but it occurs with increased frequency and number in coeliac disease. In general, BSBI does not need immediate reduction because of its spontaneously resolving nature.

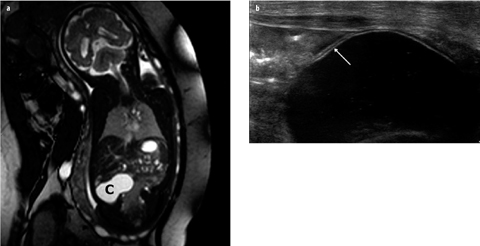

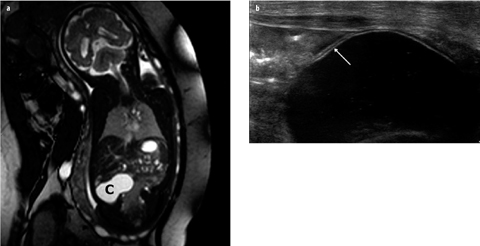

Fig. 3 a, b

Duplication cyst of ileum. a Prenatal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a cyst (C) in right abdomen. No other abnormalities are present. b Postnatal ultrasound (US) image shows gut signature of the cyst wall (arrow); during examination, intrinsic peristalsis of the cyst was seen

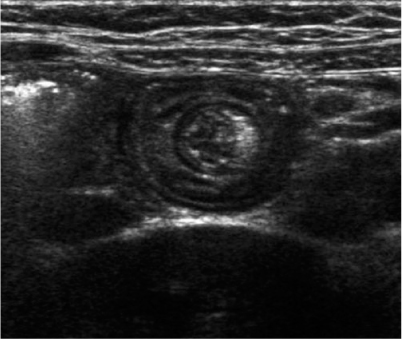

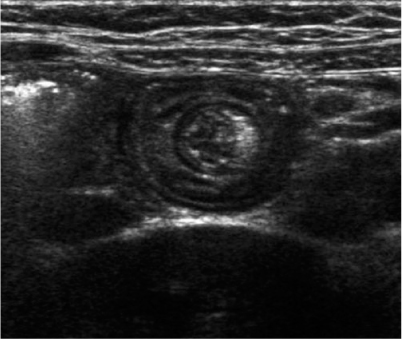

Fig. 4

Benign small-bowel intussusception in a patient without abdominal pain. Diameter 1.4 cm, persisting peristalsis, and no lymph nodes within the intussusception. The small central echogenic crescent is mesenteric fat

Appendix

This entity is also discussed separately in the Kangaroo section of this syllabus (pp. 279–288).

Large Bowel

The differences between normal small bowel and large bowel are described in the paragraph on the small bowel.

Three US patterns can be distinguished [28]:

Stratified thickening is found in infectious colitis, advanced appendicitis, and IBD (both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease)

Nonstratified thickening with loss of haustral folds is found in early HUS and advanced Crohn’s disease

Nonstratified imaging with preservation of normal haustral fold length is found in pseudomembranous colitis and neutropenic colitis (typhlitis).

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is also discussed in the paragraph describing the small bowel in this chapter. Right-sided colonic involvement is most common. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease will eventually lead to loss of stratification and pericolic fat proliferation. Because of its anatomical location (descending and ascending colon), the pericolic inflammation can extend into the retroperitoneal space and cause hydronephrosis. However, in early Crohn’s disease, these features are not yet present, and differentiation based on imaging findings is difficult, even impossible, when there is pancolitis without involvement of the terminal ileum.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a noninfectious inflammation with diffuse, uniform mucosal inflammation with involvement of the mucosa and superficial submucosa. It is limited to the colon. Onset may be insidious, with abdominal pain and recurrent diarrhea and weight loss. Nonintestinal symptoms may be present, such as growth failure, mal-nutrition, amenorrhea, arthritis, and cutaneous and ocular manifestations. Rectal bleeding is more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. Ulcerative colitis begins in the rectum and advances proximally without skip lesions. Pancolitis is frequent in children. On US, mural stratification is clearly visible because the inflammation remains superficial. The inflammation causes an increased muscle tone, and the lumen is collapsed.

Infectious Colitis (Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Yersinia)

Infectious colitis has a similar US pattern as ulcerative colitis, with preserved stratification and normal pericolic fat. In contrast with ulcerative colitis, colonic involvement is often right sided, and in more than one third of patients, distal ileum/ileocecal valves are involved. Otherwise, the diagnosis of infectious colitis depends on stool and blood cultures and analysis.

Neutropenic Enterocolitis (Typhlitis)

Neutropenic enterocolitis is a severe infectious colitis in children with neutropenia. Mainly, the cecum and ascending colon are involved, but the small bowel can be involved also. The pathogenesis is complex and involves mucosal damage, compromised immunity, bacterial invasion, distensibility, and vascularization [29]. Also, clostridial toxins are proposed as causative agents. It is often found in children with leukemia during chemotherapy. Symptoms are fever, diarrhea, and right lower quadrant pain. US demonstrates severe colonic wall thickening with loss of stratification, a redundant inner layer of increased echogenicity, and intense mural hypervascularity [30–32].

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis is usually caused by overgrowth of Clostridium difficile (together with its toxin) in patients on antibiotic therapy. Symptoms include abdominal pain, watery diarrhea, fever, and leucocytosis after recent use of antibiotics. Pseudomembranes originate from deep crypt abscesses that erupt to the surface and are formed by coalescence of mucus, fibrin, epithelial cell debris, inflammatory cells, and exudate. Depending on its composition, the pseudomembrane can be of varying thickness and echogenicity. Haustrations are preserved and not shortened, as in many other types of colitis. The pattern of swollen preserved haustrae is known as the accordion sign.

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) is a triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure. It is thought to be caused by systemic spread of bacterial toxins, e.g., Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli (STEC). Most cases occur in children younger than 5 years of age. US signs include considerable thickening of the colon wall and increased echogenicity of the renal parenchyma. The thickened wall shows loss of stratification and is strikingly avascular on color-Doppler US, especially in the prodromal phase [33]. Because the colitis often precedes the full-blown clinical presentation of HUS, the radiologist may be the first to suggest the diagnosis in a child with colitis and bloody diarrhea.

Juvenile Polyps

Juvenile polyps are the most common neoplasms in the large bowel in children. The sigmoid and rectum are preferential locations. The presenting symptom is rectal bleeding in >90% of patients; occasionally, a colocolic intussusception is the first manifestation. US will demonstrate a pedunculated spherical nodule with a diameter varying from 10 to 25 mm containing multiple 2- to 3-mm cysts. Administration of fluid within the bowel lumen will greatly improve visualization of these polyps; however, the assessment of rectal polyps is still unreliable. Specific particles within the stools may mimic polyps (e.g., undigested food, pellets of stool).

Epiploic Appendagitis

Epiploic appendagitis is a localized inflammation caused by torsion and ischemia of an epiploic appendage. These are small, peritoneal-covered fat tags at the serosal or antimesenteric border of the colon with a single artery and vein in the pedicle. Epiploic appendagitis is rare in children, but its recognition is important to prevent surgery in this self-limiting disease. It causes localized pain that will direct the sonographer toward the right site. The inflamed appendage is seen on US as a hyperechoic mass sometimes surrounded by thickened hyperechoic pericolic fat [34, 35]. In obese children, it is better appreciated with CT or MRI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree